November 23, 1984, 40 years ago: It is the day after Thanksgiving, and this was the early days of retail treating it as "Black Friday," the biggest shopping day of the year, which has come to, traditionally, set the tone for the Christmas season: Either they will make big profits, and be "in the black"; or they will be wearing black for mourning.

Thanksgiving weekend is also a time for football. The day before, many high school games were played, much more so than are played today. I was a sophomore at East Brunswick High School in Central New Jersey, and my Bears came back from a 27-13 deficit to beat Colonia High School of Woodbridge, 33-27, and clinch the Championship of the Middlesex County Athletic Conference and an undefeated regular season. It's often regarded as the greatest football game in the school's history. Unfortunately, we lost the Central Jersey Group IV Final, costing us a "State Championship" and an undefeated full season, something, to this day, we've never had.

There was only one college football game that Thanksgiving Day, a minor rivalry to everyone but those connected to the schools playing: Miami University of Ohio beat the University of Cincinnati, 31-26 at Nippert Stadium in Cincinnati. Miami University, in Oxford, Ohio, was founded in 1809, 8 years before Ohio gained Statehood. In contrast, the University of Miami, in suburban Coral Gables, Florida, wasn't founded until 1925.

In the NFL, both of the traditional home teams won: The Detroit Lions beat the Green Bay Packers, 31-28 at the Silverdome in Pontiac, Michigan; and the Dallas Cowboys beat the New England Patriots, 20-17 at Texas Stadium in Irving.

There was only one college game played on the day after Thanksgiving, on CBS. So anybody who wanted to watch a football game at that point was watching it. At the time, there was a Big East Conference, but they did not sponsor a football competition. If they did, this game would have decided its Championship. The fact that both teams involved have since moved to the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) should not attract from what that meant.

The University of Miami were the defending National Champions, having shocked the University of Nebraska in the previous season's Orange Bowl game, in the stadium of the same name, which was the Hurricanes' usual home field.

Bernie Kosar quarterbacked them as a freshman, and now, as a sophomore, had led them to an 8-3 record. They had won the Kickoff Classic at the Meadowlands, beating then-Number 1 Auburn. They beat Number 17 Florida on neutral ground in Tampa. They beat Number 16 Notre Dame away. But they had lost to Number 14 Michigan away, losing the Number 1 ranking in the process. They had lost to Number 15 Florida State at home.

And, in their last game before this one (they had a week off in between), they lost an embarrassing one: They led Maryland 31-0 at the half, and lost, 42-40. For many years thereafter, it was the biggest comeback in NCAA Division I-A (now FBS, the Football Bowl Subdivision) history. The Maryland quarterback was Frank Reich, substituting for the injured Boomer Esiason. In the 1992 NFL Playoffs, subbing for the injured Jim Kelly -- who had played at Miami -- Reich led the Buffalo Bills to what is still the biggest comeback in NFL history, from 35-3 down to beat the Houston Oilers, 41-38 in overtime.

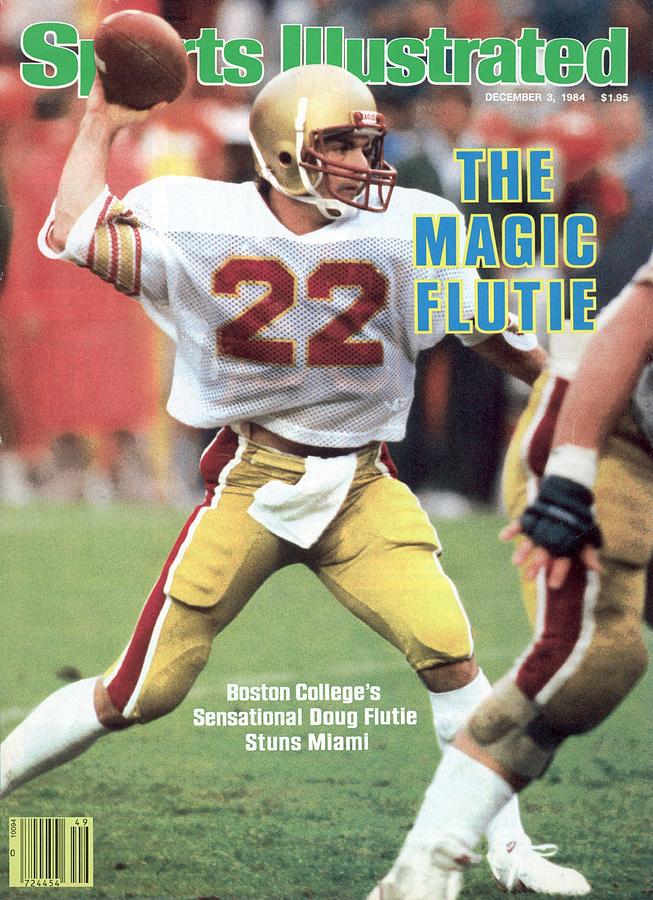

Their opponents for this game would be Boston College. BC had some good teams in the 1930s and '40s, but hadn't done much since. In 1981, they were struggling, losing to the University of Pittsburgh, ranked Number 2 in the country, and coach Jack Bicknell turned to a 5-foot-9 3/4-inch freshman quarterback from nearby Natick, Massachusetts, and said, "Okay, Flutie, see what you can do."

And Doug Flutie went in, and nearly pulled the upset. They ended the season 5-6. The next season, Sports Illustrated noted that Flutie would be the starting quarterback, and whoever was writing the article finished with, "Good luck, Flutie."

Flutie made his own luck, leading BC to an 8-3-1 record. Their non-wins were all against then-ranked teams: A tie away to Number 16 Clemson, and losses away to Number 16 West Virginia, home to Number 8 Penn State, and to Number 18 Auburn in the Citrus Bowl. It was their 1st bowl game in 39 years.

As a junior in 1983, Flutie led them to a 9-3 season, losing at home to Number 12 West Virginia, away to unranked Syracuse, and in the Liberty Bowl to Notre Dame. On October 29, in a game too big for their 32,000-seat on-campus Alumni Stadium, they played defending National Champion (but, at the time, unranked) Penn State at Sullivan Stadium, home of the NFL's New England Patriots (later renamed Foxborough Stadium). Before a crowd of 56,605, and millions more watching on ABC, the Eagles beat the Nittany Lions, 27-17. Flutie, already the classic "local boy makes good," became a national star.

BC were 7-2 going into their game with Miami. They had beaten Number 9 Alabama in Birmingham, but had lost 2 games, away to Number 20 West Virginia and away to Penn State -- by a combined 8 points. BC were ranked Number 10, Miami Number 12. In spite of these rankings, Miami were a 6-point betting favorite. (Keep in mind: In football, home-field advantage is traditionally said to be worth 3 points.) Flutie was the favorite for the Heisman Trophy, although Kosar was also a contender for it. The winning quarterback would get his Heisman vote totals boosted significantly.

The game was played at the Orange Bowl, in a driving rainstorm throughout. It was almost as if there was a real hurricane going on. It kicked off at 2:30 PM Eastern Time, and BC jumped out to a 14-0 lead. Miami scored a touchdown before the 1st quarter ran out, and tied the game with a touchdown early in the 2nd quarter.

BC scored on a run by Flutie, then Miami scored on a Kosar touchdown pass, then BC did so on a touchdown pass from Flutie to his college roommate, Gerard Phelan. At halftime, the score was Boston College 28, Miami 21. So there had already been as much action as in most full games.

In the 3rd quarter, Miami scored another touchdown, and the teams traded field goals. The quarter ended with the game tied, 31-31. BC kicked another field goal to make it 34-31, but Melvin Bratton broke off a 52-yard run to make it 38-34 Miami. It seemed like Miami had the game won. Flutie led a drive that ended with a touchdown, and it was 41-38 BC. But Kosar led a drive that ended with another touchdown run by Bratton, and it was 45-41 Miami.

BC got the ball back with 28 seconds left in regulation, on their own 20 yard line. Flutie got the Eagles to the Hurricanes' 48-yard line. There were 6 seconds left. Time for one more play. A field goal wouldn't have helped, it would have been 65 yards anyway, and the weather and the wet grass would have made it a tricky proposition regardless of how close it was. There was no choice: The play had to result in a touchdown.

Before the play, CBS announcer Brent Musberger said, "One thing is certain: Those brave folks who sat out here in the Orange Bowl, and put up with this terrible weather, saw a whale of a football game, and they should give both teams a rousing ovation when this one is over." His broadcast partner, former Notre Dame coach Ara Parseghian, whose career included a 10-10 tie with Michigan State in 1966, known as "The Game of the Century," followed this with, "This is one of the better ones that I've seen."

Flutie called "55 Flood Tip": No running backs, and all eligible receivers run straight routes to the end zone. He was flushed out of the pocket by the Miami defense, and had to scramble. He had to attempt his 46th pass of the game, on the run, throwing from his own 37-yard line, meaning the ball had to fly at least 63 yards, into a 30-mile-per-hour wind, and through the rain.

Flutie heaved the ball. Since a Roger Staubach to Drew Pearson play in the 1975 NFL Playoffs, such a pass had been known as a "Hail Mary." Some Catholics find the expression offensive. In this case, given that Boston College is a Catholic school -- specifically, Jesuit -- it might have been appropriate.

Three Miami defensive backs blanketed receiver Kelvin Martin. There would be no way he could catch the ball. Phelan was behind them. It would require perfect placement of both man and ball for him to catch it. He did. Boston College 47, Miami 45. Ballgame. No chance to try for an extra point, with everyone running onto the field, and no need for it.

"Caught by Boston College!" Musberger yelled. "I don't believe it! It's a touchdown! The Eagles win it! I don't believe it! Phelan is at the bottom of that pile!" The entire team piled onto Phelan. As Musberger noted, "Jack Bicknell is the only person over there on the sidelines! He couldn't get the headset off fast enough! Doug Flutie has done it! And your heart goes out to Bernie Kosar. He did everything he could."

Kosar had passed for 447 yards, then a school record, with 2 touchdowns. And Bratton had run for 4 touchdowns. It was all for naught, as Flutie passed for 472 yards, becoming the 1st major college quarterback with 10,000 career passing yards. He also threw for 3 touchdowns. Miami punted only once all game; BC, just 3 times.

The game became known as the Miracle in Miami, and if there was any doubt before the game that Flutie would win the Heisman Trophy, that doubt disappeared into Phelan's hands. Ohio State running back Keith Byars finished 2nd. Robbie Bosco, who quarterbacked Brigham Young University to a controversial National Championship, finished 3rd. Kosar was 4th. Jerry Rice of Mississippi Valley State, who went on to become the greatest receiver in football history, finished 9th. Bo Jackson of Auburn, who would win it the next season, did not finish in the Top 10 this season.

Miami went on to lose the Fiesta Bowl to UCLA. Kosar would have a good pro career with the Cleveland Browns, before winning a Super Bowl ring as Troy Aikman's backup on the Dallas Cowboys.

Flutie's last college game was in the Cotton Bowl, and BC beat the University of Houston. But NFL teams passed on him due to his lack of height. This was so dumb. How dumb was it? Well, let's absolve the following teams, because they drafted Hall-of-Famers: The San Francisco 49ers, Rice; the Buffalo Bills, Bruce Smith; and the Minnesota Vikings, Chris Doleman. And, besides, the 49ers had Joe Montana, while the Bills had the rights to Jim Kelly. And several other teams drafted All-Pros. But lots of teams needed a quarterback, and didn't draft Flutie, and struggled for years to come.

Flutie signed with the New Jersey Generals of the United States Football League, and led them to the Playoffs. When the USFL folded, the Chicago Bears signed him, against the wishes of head coach Mike Ditka. Ditka refused to start him over an already-injured Jim McMahon, and the Bears haven't won a Super Bowl since. In 1987, the Bears traded Flutie to his hometown New England Patriots, but they kept him as a backup to Tony Eason, and didn't get too far, and released him after the 1989 season, and got even worse.

Flutie signed with the Vancouver-based BC Lions of the Canadian Football League. In 1992, he was traded to the Calgary Stampeders, and he led them to the CFL Championship, the Grey Cup. He did the same for the Toronto Argonauts in 1996 and '97. All 3 times, he was named the game's Most Valuable Player. He was named the CFL's Most Outstanding Player 6 times in 7 years from 1991 to 1997.

Finally, at the age of 36, the NFL could ignore him no longer. With Kelly having retired after the 1996 season, the Bills signed Flutie, and he led them to the Playoffs, made the Pro Bowl, and was named the NFL Comeback Player of the Year. He got them back into the Playoffs in 1999, but coach Wade Phillips benched him for the Playoff game against the Tennessee Titans, in favor of Rob Johnson. The Bills lost, and didn't make the Playoffs again for 18 years.

Flutie played 4 years for the San Diego Chargers, and closed his career with the Patriots, as a backup to Tom Brady. In his last game, against the Miami Dolphins, on New Year's Day 2006, he did something no NFL player had done since 1941: He converted a dropkick. It was good for a point-after-touchdown, and the Patriots won.

Doug Flutie is not in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. It is, quite specifically, not "The National Football League Hall of Fame." It includes a few players who would not have made it if not for their performances in the All-America Football Conference (1946-49) and the 1960s version of the American Football League, including Billy Shaw, who played 9 seasons for the Bills, all in the AFL, and never played a down in the NFL.

Still, voters for it tend not to consider CFL statistics. There are really only 2 NFL players who are not in the Hall whose qualifications would be noticeably boosted if their CFL tenures were included, and they're both quarterbacks: Joe Theismann and Doug Flutie. Another quarterback, Warren Moon, is the only player in the Hall with significant CFL performance, although Bud Grant won 4 Grey Cups as a coach in Winnipeg before becoming a Hall of Fame coach in Minnesota.

Oddly, for all the exposure BC got from the Flutie years, their Alumni Stadium wasn't expanded to its present 44,500 seats until the 1994 season.