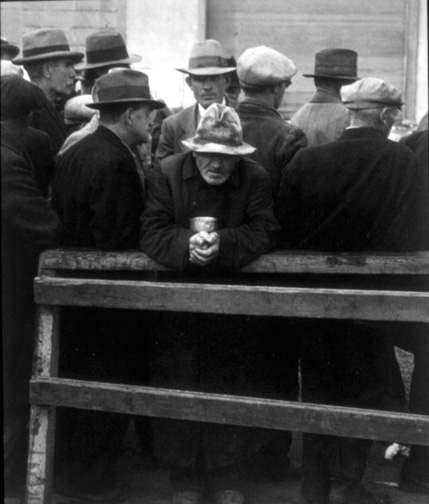

Five Montreal Canadiens legends. Left to right:

Guy Carbonneau, Guy Lafleur, Jean Béliveau,

Maurice Richard and Pierre Turgeon.

March 11, 1996, 30 years ago: The last hockey game is played at the Montreal Forum, the greatest of all hockey arenas.

It had opened on November 29, 1924. The Montreal Canadiens defeated the Toronto St. Patricks, the team that would become the Toronto Maple Leafs, 7-1. Billy Boucher scored the arena's 1st goal. He was 1 of 4 brothers in the NHL. Frank was the original star of the New York Rangers. Georges "Buck" Boucher starred for the Ottawa Senators. Frank and Buck both made the Hockey Hall of Fame. Billy was known for his rough play with the Canadiens, and Bobby Boucher (not to be confused with Adam Sandler's character in The Waterboy) barely played in the NHL, also for the Canadiens.

Originally, the Forum wasn't meant to be the Canadiens' home. It was meant to be the home of the Montreal Maroons, a newly-founded team, while the Canadiens continued to play home games at the Mount-Royal Arena. The Maroons' 1st game at the Forum came on December 3, but they lost to the Hamilton Tigers, 2-0.

The Maroons won the Stanley Cup in 1926. For the next season, the Canadiens moved in, and the Forum was busier than ever: Its 9,300 seats played host to the Canadiens or the Maroons every Thursday and Saturday, the Quebec Senior Hockey League on Wednesdays and Saturdays, the Quebec Junior Hockey League on Mondays, the Bank League on Tuesdays, and the Railways and Telephone League on Fridays.

The Canadiens' famed "CH" logo has confused people for over a century. It is short for the team's official name, le Club de hockey Canadien. Madison Square Garden president George "Tex" Rickard, boxing promoter and founder of the Rangers, probably without knowing the truth, told a reporter that the "H" stood for "Habitant," a term used to describe farmers in early Quebec. Ever since, the Canadiens have been known as Les Habitants, or the Habs for short. The chant became, "Go, Habs, go!"

The Canadiens won the Stanley Cup in 1916 and 1924, before the Forum opened. They won it in 1930 and 1931, led by Howie Morenz, the man eventually known as "the Babe Ruth of Hockey." In 1937, Morenz broke his leg during a game, was hospitalized, and died of a heart attack in the hospital. A benefit game was played at the Forum, between a combined team of Canadiens and Maroons against a team made up of players from the rest of the League. A few months later, at the end of the 1937-38 season, the Maroons went out of business, due to the Great Depression.

In 1942, Maurice Richard arrived on the Canadiens' roster. "The Rocket" led them to 8 Stanley Cups. In 1953, along came Jean Béliveau, and he led them to 10. Richard's last 5 and Béliveau's 1st 5, from 1956 to 1960, were the only instance ever of 5 straight Cup wins.

They followed the 1955 season, in which an incident in Boston led to Richard's suspension for the Playoffs, which led to a riot inside the Forum that spilled out into the streets. French-Canadians, for whom the Canadiens, and Richard in particular, were a point of pride were angry at Clarence Campbell, the NHL's Anglophone President, suspending him, thinking he was trying to fix the Cup for an Anglophone team. Richard went on radio and told the fans to stop, that he would take his punishment, support the team to win the Cup this time, and play to win it in the future.

They lost the Finals to the Detroit Red Wings, but with Richard joined by his brother Henri, Béliveau, defenseman Doug Harvey and goalie Jacques Plante, won those next 5 Cups. Henri actually topped his brother, and Béliveau, by being a member of 11 Cup-winning teams. In all of North American sports, only Bill Russell of the NBA's Boston Celtics matched Henri Richard's 11 World Championships.

In 1968, the Forum was seriously renovated, and expanded, to a seating capacity of 16,259, plus 1,700 in standing room, for a total of 17,959. The support poles were removed. One thing that was retained: Whereas most arenas used a horn to signal the end of a period, the Forum used a high-pitched siren, which was kept after the move to the Bell Centre.

In 1972, the Forum hosted the 1st game of the 8-game "Summit Series" between Canada and the Soviet Union, which the Soviets won in a 7-3 shocker. Canada would win the series with dramatic wins in Moscow in Games 6, 7 and 8.

From 1976 to 1979, the Canadiens had a run of 4 straight Cups, led by a slew of Hall-of-Famers: Forwards Guy Lafleur, Yvan Cournoyer, Steve Shutt and Jacques Lemaire; defensemen Larry Robinson, Serge Savard and Guy Lapointe; and goaltender Ken Dryden.

Between them, Morenz, Maurice Richard, Béliveau and Lafleur were, effectively, the Mount Rushmore of hockey. They were a foursome that could only be matched in North American sports by the Yankees' Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle. (The Celtics? Bill Russell and Larry Bird, but who are the other two? Bob Cousy and John Havlicek? Not the same. No football team can match it, either.)

From 1956 to 1979, the Canadiens won 15 of the 24 available Stanley Cups. Their 1979 Cup was their 22nd, matching the Yankees for the most World Championships in North American sports. They won a 23rd in 1986 and a 24th in 1993. The Yankees didn't win their 24th World Series until 1998, surpassing them with a 25th in 1999.

In the 1976 Olympics, the Forum hosted basketball, boxing, volleyball, handball, and gymnastics, including Nadia Comaneci registering the 1st perfect 10 in Olympic history -- 7 of them.

The Beatles played the Forum on September 8, 1964. Other notable concerts there included Bob Dylan's Rolling Thunder Revue in 1975, Bob Marley in 1978, and, all in separate shows in 1981, Rush, Queen, and the Jacksons.

But there was only so much that could be done with a 1924-built arena. So construction began on a new arena. And on March 11, 1996, the Forum's final game was played, against the Dallas Stars. They were chosen as the opponent because their Captain was a former Canadiens' Captain, Guy Carbonneau. Maurice Richard, Béliveau and Lafleur participated in a ceremonial puck-drop with Carbonneau and Canadiens Captain Pierre Turgeon.

Turgeon opened the scoring, Mark Recchi made it 2-0, Derian Hatcher got the Stars on the board, Saku Koivu scored, and the last goal at the shrine of hockey was scored by... Andrei Kovalenko, a Russian right wing of Ukrainian descent, at the 13:56 mark of the 3rd period. Final score: Canadiens 4, Stars 1.

In the Canadiens' locker room, replicated at the new arena, the lockers were topped by the faces of the team's members of the Hockey Hall of Fame. On each side, one in English and one in French, are words from Canadian Army doctor John McCrae's World War I poem In Flanders Fields: "To you from failing hands we throw the torch; be yours to hold it high." (En Francais: Nos bras meurtris vous tendent le flambeau; a vous toujours de la porter bien haut.)

After the last game at the Forum, a symbolic torch was passed from the earliest living Canadiens Captain, Butch Bouchard, to each succeeding Captain: Bouchard, Maurice Richard, Jean Béliveau, Henri Richard, Yvan Cournoyer, Serge Savard, Bob Gainey, Carbonneau, up to Turgeon. (Kirk Muller and Mike Keane, each serving as Captain between Carbonneau and Turgeon, were playing with other teams, and thus unavailable.)

When Rocket Richard, the most popular player in Canadien history, was introduced, he got a standing ovation that brought him to tears. Given the uniform number he made famous, it was appropriate that it lasted for 9 minutes.

The Canadiens played an away game on March 13, a 1-1 draw with the New Jersey Devils at the Meadowlands, before going back to Montreal to play the 1st game at the Molson Centre, since renamed the Bell Centre, about a mile to the east, in Centre-Ville (downtown). In a special pregame ceremony, Turgeon took the torch from the last game, and lit a new one inside the arena. With Vincent Damphousse scoring the 1st and 3rd goals in the new arena, the Canadiens beat the New York Rangers, 4-2.

Over the next 4 years, a construction company owned by 1950s Canadien Hall-of-Famer Dickie Moore converted the Forum into retail space, including a shopping mall and a movie theater. A small bleacher section, and a bench with a statue of Maurice Richard, are roughly where center ice was.

The repurposing of the Forum helped to inspire a similar construction job at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, after it closed in 1999. Those arenas still stand, unlike the other "Original Six" arenas: The old Madison Square Garden was torn down in 1968, the Olympia Stadium in Detroit in 1986, the Chicago Stadium in 1995, and the Boston Garden in 1998.