But there's no way this song would have been released as a record, because it was racially motivated. Sam sung of visiting Chinatown, on Addison Road. He dragged out the A on "Addison," not like a New York or Newark accent, but beautifully.

There is no Addison Road in Sam's hometown of Chicago, but there is an Addison Street, on the North Side, and Wrigley Field, home of baseball's Chicago Cubs, is at its intersection with Clark Street. There is a song titled "Allison Road," but that was a hit for The Gin Blossoms, in 1994, 30 years after Sam's life came to a tragic and suspicious end at a "no-tell motel" in Los Angeles.

And Chicago does have a Chinatown, but it's on the South Side. Sam grew up, at 724 E. 36th Street, in a neighborhood known as Bronzeville for having so many black people living there. (A housing project is now on the site, facing Ellis Park.) Chicago's Chinatown is about a mile to the northwest, usually said to be bounded by 18th Street, Clark Street, Cermak Road (formerly 20th Street) and the South Branch of the Chicago River.

In the song, Sam spoke of his "brothers," which I took to mean a group of black men, meeting with the men of Chinatown, and teaming up in an "uneasy peace." I took "Uneasy Peace" to be the title of the song.

To my dismay, I woke up after hearing only the 1st verse. Would such an alliance have worked? Would they have moved on to a team-up with Latinos, of which Chicago already had many? There was a rise in Native American activism by the end of the 1960s, and even in 1965, Johnny Cash had an album of songs about "Indians," called Bitter Tears, so maybe they could have been added to the "uneasy peace."

I wanted to hear what happened next. Now, I never will. But I know this: If the song were real, Sam couldn't have released it. If the musical South Pacific (on stage in 1949 and in film in 1958) had to use Polynesian people as a stand-in for black people, and the musical West Side Story (on stage in 1957 and in film in 1961) had to use Puerto Ricans as an analogue for blacks, and the people backing those stories needed to use allegories to get their point of "bigotry is bad" across, there's no way the white establishment would have let Sam use a song about African-Americans and Asian-Americans teaming up, for a fight with a white gang, or simply to stand up for their rights to the white establishment.

Given that he was killed 5 months after the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a little over a year after the March On Washington and the Birmingham Church Bombing, a year and a half after the assassination of Medgar Evers, 3 months before Bloody Sunday in Selma, and 8 months before the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed and the Watts riot broke out not far from where he was killed, there's no way even someone with Sam's clout would have gotten away with it.

No way. Radio networks would have told their disc jockey not to play it. Sponsors of those networks would have stepped in to tell them, "Don't play it," even before the networks could tell their DJs. The people who bankrolled newspapers wouldn't have allowed print ads for the record.

Forget TV. Sam was signed to RCA Victor Records, which gave him a good deal of leeway, but not that much, and RCA also owned NBC, so Sam wasn't going to be singing that song on The Tonight Show or in a "spectacular." (By the end of the 1960s, they were being called "specials.") Ed Sullivan liked Sam, gave him his national TV debut in 1957, and had no problem with putting black people "here, on this great stage" on his "really big shew," from the beginning to the end; but CBS chairman Bill Paley and his lawyers would have put the kibosh on having Sam sing such a song. Even Sam's unintentional farewell song, the powerful but hardly offensive "A Change Is Gonna Come," might not have been allowed on the air.

Would the song have helped to widen the dialogue on race relations? Would it have helped Asians as well as blacks? Would it have helped to forge, if nothing else, an "uneasy peace" between both groups and white people? Or would it have angered white people to the point of making things worse?

I'd like to think the 2nd and 3rd verses of the song would have had a theme of, "Listen to us. Listen to your black, brown, yellow and red brothers and sisters. Your national creed says, 'All men are created equal.' That includes us. We're not asking for special treatment, just equal treatment. Give us the same chances you give each other."

It would have been a powerful message in 1965. It would be a powerful message in 2026, with Donald Trump sending men with Nazi-style tactics to round people up in Portland, Maine and Portland, Oregon -- and, apparently, to murder people in cold blood in Minneapolis.

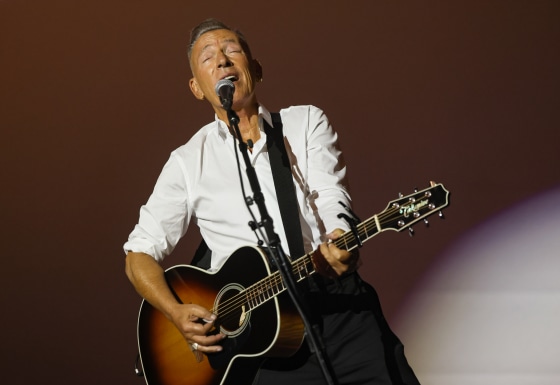

When I heard Bruce Springsteen's rush-written, but superbly-written, new song "The Streets of Minneapolis" -- a very different song from his epic "The Streets of Philadelphia" -- and then an even angrier song on the subject by British singer Billy Bragg, I wrote this online:

Bruce Springsteen is 76. Billy Bragg is 68.

Beyoncé is 44. Bruno Mars is 40. Lady Gaga is 39. Kendrick Lamar is 38. Taylor Swift is 36. Morgan Wallen and Ariana Grande are 32. Megan Thee Stallion and Post Malone are 30. Sabrina Carpenter is 26.

What are they doing?

The implication being that these are performers in their prime, who reach more music fans than anybody else, and thus should be doing what these old men are doing, but aren't.

Less than 24 hours after I posted it, Lady Gaga released a cover of Mr. Rogers' theme song, "Won't You Be My Neighbor?" A lot of people said it was just what we need at this time. It doesn't directly address the subject at hand, any more than did Elvis Presley's "If I Can Dream," which closed his 1968 "Comeback Special." But, like that song, it seems to send a message of hope and brotherhood. So Gaga is off the hook: She rose to the occasion.

The rest of them, they're "on the clock." Time for them to step up. Taylor talks a good game, but she really doesn't back it up well. Megan is great on personal empowerment, but she hasn't tried to do a rally-the-people song. Kendrick has, but "Not Like Us" isn't on the same level as what Bruce just did.

One of these people needs to step up, the way Bruce did, before other old men like Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan and Paul Simon do so. Sam Cooke would be 95 if he had lived, so he'd almost certainly be out of the picture, anyway.

But we need the great performers of this time to stand up and make themselves heard on the great issues of the day, as has happened before. Bruce must be feeling like the old women at protests holding up signs referring to their previous activism.

At this point, an "uneasy peace" would be preferable to the "cold civil war" that Trump launched in 2015, and, from then until June 2020, and against from November 2024 until this week, seemed to be winning.

Now, the outcome is again in doubt. It's time for the great artists to launch "D-Day."

I don't know if there will be a "Hiroshima," but there must be a "Battleship Missouri Surrender."

No comments:

Post a Comment