Nebraska had put together one of the greatest seasons in college football history. They began it ranked Number 1, and opened in the Kickoff Classic at the Meadowlands, against Number 4 Penn State, and won 44-6.

The Cornhuskers scored more points than anyone had seen in the modern era. They beat Minnesota away 84-13. They beat Iowa State 72-29. They beat Colorado 69-19. They beat Kansas 67-13. They beat Syracuse 63-7. They beat Wyoming 56-20. They beat Kansas State away 51-25. They beat UCLA 42-10.

Not all their games were easy. They went to Missouri and beat them "only" 34-13. In what was then their biggest rivalry, they went to Oklahoma and beat them 28-21. Aside from Penn State, the only ranked team they played was Number 20 Oklahoma State, away, and escaped with a 14-10 win. Still, they were 12-0, scoring 624 points and allowing just 186, for an average score of 52-15.

How good was that opposition: Minnesota went just 1-10, beating only Rice, who also went 1-10. Kansas State went 3-8. Kansas went 4-6-1. Iowa State and Colorado both went 4-7.

But Penn State went 8-4-1, won the Aloha Bowl, and finished ranked Number 17. Oklahoma went 8-4, and probably would have been ranked and gotten a bowl bid, had they not been on probation. Oklahoma State also went 8-4, won the Bluebonnet Bowl, and was ranked Number 18. UCLA went 7-4-1, won the Pac-10 and the Rose Bowl, and was ranked Number 13. Wyoming went 7-5. So did Missouri, who went to the Holiday Bowl, but lost. Syracuse went 6-5. So the 'Huskers were doing more than just running up the score on weak opposition.

Head coach Tom Osborne was named National Coach of the Year. Running back Mike Rozier won the top 2 Player of the Year awards, the Heisman Trophy and the Maxwell Award. Guard Dean Steinkuhler won the top 2 Lineman of the Year awards, the Outland Trophy and the Lombardi Trophy. Rozier, Steinkuhler and receiving Irving Fryar were named 1st team All-Americans; quarterback Turner Gill, 2nd team. Each of those was named to the All-Big Eight Conference 1st team, along with offensive tackle Scott Raridon and center Mark Traynowicz.

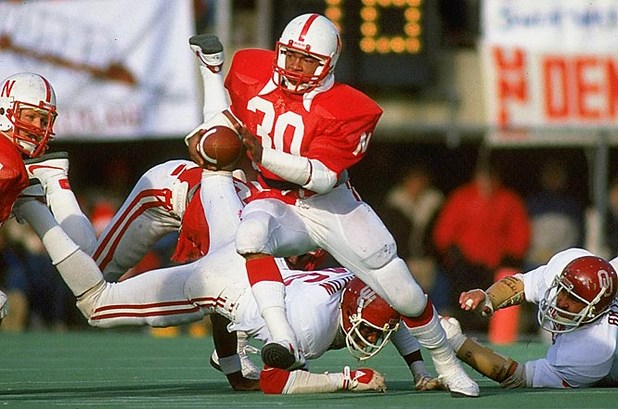

Mike Rozier

Rozier and Steinkuhler would go on to become All-Pros with the Houston Oilers. Fryar would go to the Pro Bowl with the New England Patriots, the Miami Dolphins and the Philadelphia Eagles, and get to a Super Bowl with the Patriots. Running backs Doug DuBose and Tom Rathman would go on to win a Super Bowl with the San Francisco 49ers. (Rathman would win 2 with them.) Defensive end Jim Skow would reach a Super Bowl with the Cincinnati Bengals. Gill is now an administrator at the University of Arkansas, after winning conference titles as head coach at the University of Buffalo and Liberty University.

The Hurricanes, then an independent, were no slouches. Their previous 3 seasons saw them go 9-3, 9-2 and 7-4, and they were 10-1 this season. After losing their opener at Number 16 Florida, they had shut out Purdue and Number 13 Notre Dame, held Number 12 West Virginia to 3, and held 4 teams to just 7 points: Houston, Mississippi State, Cincinnati and East Carolina (and only the last of these was at home).

But they only had 2 games that compared to Nebraska's blowouts, winning 56-17 away to Duke and 42-14 at home to Louisville. Their last game before the Orange Bowl was away to arch-rival Florida State, and they escaped 17-16 winners.

Unlike later Miami teams, coach Howard Schnellenberger's '83 'Canes were not loaded with future NFL talent, but they did have Bernie Kosar, a redshirt freshman quarterback, who would later make some noise. And they would be playing the Orange Bowl game in the Orange Bowl stadium, their home field. Nevertheless, Nebraska went into the game favored by 10 1/2 points -- maybe the greatest insult an 10-1 team playing at home had ever received.

The day's other bowl games played into both teams' hands. In the early game, the Cotton Bowl in Dallas, Number 2-ranked Texas lost to Georgia. In the afternoon, the Rose Bowl in Pasadena saw Number 4 Illinois lose to UCLA. And, while the Orange Bowl was going on, Number 3 Auburn was struggling against Michigan in the Sugar Bowl in New Orleans.

So the National Championship was likely to come down to the winner of the Orange Bowl: Nebraska would have won the title with a win, anyway; while, if Miami won, and Auburn lost, or if Auburn didn't win convincingly, Miami could jump from 5th to 1st.

*

And, just as the New York Jets had done to the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III on the same field, 15 years to the month earlier, the 'Canes shocked everybody. They held Nebraska to a field goal attempt by Mark Hagerman on the 1st possession of the game, and blocked it.

With the momentum on their side, and with a key interception later, the 'Canes jumped out to a 17-0 lead in the 1st quarter. Only Colorado and Iowa State had managed more than that on Nebraska in 3 quarters, before the backup defenders had been put in.

Nebraska settled down, and closed to within 17-14 at the half. Early in the 3rd quarter, a Miami fumble gave Nebraska the ball deep in Hurricane territory, but, again, the 'Canes held the 'Huskers to a field goal attempt, which Hagerman made, to tie the game at 17.

Before the quarter ended, Kosar engineered 2 more touchdown drives, to make it 31-17 Miami. Rozier, the best player in the country all season long -- he got 482 1st-place votes for the Heisman Trophy, and Brigham Young quarterback Steve Young was next-best with 153 -- had to leave the game with an ankle injury, taking the 'Huskers' best weapon away. And Jeff Smith, subbing for Rozier, got off a 40-yard run, but was stripped of the ball at the 1-yard line, and Miami recovered.

Early in the 4th quarter, Nebraska was held to another field goal attempt, and, unlike the early blocked attempt, Hagerman simply missed this one. Nebraska later scored a touchdown to make it 31-24, and then it was Miami's turn to miss a field goal attempt.

With less than 2 minutes to go, Gill passed to Fryar, who got inside the Miami 35-yard line. On 2nd and 8 from the Miami 24, Fryar was wide open in the end zone, but dropped Gill's pass. It went to 4th and 8, and Gill threw to Smith, who got into the end zone. That made it 31-30.

Now, Osborne had a decision to make: Kick the extra point, make it 31-31, and settle for a tie -- or, maybe, go for the onside kick, hope you get into field goal range, but also risk Miami winning it with a field goal -- or go for a 2-point conversion and a 32-31 win, with Miami still having time to maybe get into field goal range. Earlier in the week, he was asked about this very situation, and said, "I hope it doesn't come up."

It now had. With overtime not available (and this would remain true for college football until the 1996 season), Osborne decided to go for 2. The ball was placed on Miami's 3-yard line. Once again, Gill rolled to his right, and looked for Smith. But Smith was double-covered, and Kenny Calhoun knocked the pass away.

A recent photo of Kenny Calhoun, "Throwing the U"

Nebraska kicked off, and Miami ran out the clock. Auburn ended up winning the Sugar Bowl only 9-7, and, when the Associated Press and United Press International released their polls the next day, they both awarded Miami the National Championship. The AP (the sportswriters) gave 11-1 Miami 47 1/2 1st-place votes, 11-1 Auburn 7, and 12-1 Nebraska 4 1/2. UPI (the coaches) gave Miami 30, Nebraska 6, and Auburn 4.

Bernie Kosar, on an NBC screen capture

With a little bit of irony, Jeff Smith, rather than Mike Rozier, was the man on the cover of Sports Illustrated after the season-opening win over Penn State. Therefore, when "The Dreaded SI Cover Jinx" hit Nebraska, it was the player who had the chance to clinch the National Championship, 4 months later, that it gave a delayed hit.

*

This would begin a run for Miami of 12 seasons in which they were, effectively, in 6 National Championship Games, winning 4 of them (in the seasons of 1983, 1987, 1989 and 1991). They would win another in 2001 and come very close in 2002.

The '84 Orange Bowl would haunt Nebraska, which last won the National Championship in 1971, and had some other close calls. They would lose the Orange Bowl to Miami again in 1988 (thus blowing a shot at the title and letting Miami win it), and lose it to Florida State in 1994 (again blowing the title to a team from Florida).

Finally, on January 1, 1995, they again went to the Orange Bowl, again played Miami, and beat them 24-17, to win the 1994 National Championship, finally getting the monkey off Osborne's back. (He had been an assistant to Bob Devaney when they won the title in 1970 and '71.)

They would win the National Championship again in 1995, and share the 1997 title with Michigan, the last "split poll" title. That 1995 team is considered by some to be what the 1983 team should have been: The greatest team in college football history.

Osborne then retired, with a career record of 255-49-3, having coached 53 All-Americans, 13 Conference Championships (the last in the Big 12, the others in the Big 8), and 3 National Championships. In 2000, '02 and '04, he was elected to Congress from Nebraska as a Republican. He retired rather than run again in the 2006 election, to accept the post of the University of Nebraska's athletic director, a post he held until 2013. The playing surface at their Memorial Stadium is named Tom Osborne Field. He is still alive, 82 years old.

*

Did Osborne make the right choice in going for 2 in the '84 Orange Bowl?

Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame Tom Osborne for Nebraska Losing the 1983 National Championship

5. Miami Stepped Up. In situations like this, it's easy to make Reason Number 1 "The opposition was better." Only the most deluded of Hurricanes fans would say their team was better than the Cornhuskers'

But if the Hurricanes hadn't played so well, becoming college football's answer to the 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates, to Nebraska's Yankees -- or, to use an earlier-cited example from the same stadium, the Jets to the Cornhuskers' Colts -- Nebraska wouldn't have been in the position where Osborne had to make the critical decision.

4. Nebraska Blew It. All season long, they had gotten the job done, until now. And they had come back from 17-0 and 31-17 to get to 31-30. There was plenty of reason to believe they could gain 3 yards on this one play. But, between the missed field goal, the blocked field goal, the fumbled sure touchdown, and the dropped passes on the last drive, they had their chances, and they blew them.

Think about it: Had either of Hagerman's missed field goals gone through, that last touchdown would have made it 33-31 Nebraska. True, there was enough time left on the clock where the conversion would have been more meaningful at 35-31 than at 34-31, but not by that much. Had Hagerman made both of those misses, it would have been 36-31, and Miami would have needed a touchdown no matter what.

Even Osborne blew it: If he had gone for 2 on the preceding touchdown, and made it, that would have made the score 31-25, and he could have won the game 32-31 with an extra point kick on the touchdown in question. Nobody talks about that choice.

3. Principle. If you can't gain 3 yards on 1 play to win 1 game, you don't deserve to win the National Championship.

2. Ara Parseghian. As head coach of Notre Dame in 1966, he went for a tie against Michigan State, knowing it wouldn't cost him the National Championship, whereas a loss would have. But, in the ensuing 17 years, the words had been spoken many times: "Parseghian had no guts."

Osborne was not going to be accused of having no guts. He knew that, for all Parseghian had achieved, that 1966 10-10 tie was the thing for which he was most remembered. "We were trying to win the game," Osborne said at the time. "I don't think you go for a tie in that case. You try to win the game. We wanted an undefeated season and a clear-cut National Championship."

Clear-cut. Because...

1. America Hates Ties. Long ago, though the identity of the coach who first said it depends on who's telling the story, a coach lost a game on a 1-yard run attempt rather than kick a tying field goal, and explained to the reporters, "A tie is like kissing your sister."

It's not like in European soccer, where a win is worth 3 points to your team in the league standings (or "table"), and a tie (or "draw") is worth 1 point. A tie that gave Nebraska the 1983 National Championship would have satisfied very few people -- outside the State of Nebraska, anyway. America hates ties, to the point that the NHL no longer has them.

Sure, with a tie, Nebraska would still have been National Champions. But any pretense to "Greatest Team Ever" status would have been gone.

After all, as Herman Edwards, then still playing cornerback for the Philadelphia Eagles, would later put it while coaching the New York Jets, "This is what the greatest thing about sports is: You play to win the game!"

VERDICT: Not Guilty. A lot of people would have understood it if he had gone for the tie and, presumably, still won the National Championship. But 32-31 and 13-0 would have been better than 31-31 and 12-0-1.

Besides, the '95 Orange Bowl win over Miami, and the resulting National Championship, was all the sweeter because of the '84 Orange Bowl loss to Miami.

No comments:

Post a Comment