The show's creator was Barry Kemp, a graduate of the University of Iowa, whose campus, including its Kinnick Stadium, was used for exterior shots of the fictional Minnesota State University. He named the character of Hayden Fox after the head coach at Iowa at the time, Hayden Fry. But aside from a name and a job, they didn't share much. Hayden Fry was the kind of man that Hayden Fox should have been.

John Hayden Fry Jr. -- he would eventually drop his first name, perhaps to differentiate himself from his father -- was born on February 28, 1929 in Eastland, Texas. He grew up in Odessa, in West Texas, which was too dry to get good farming, and there seemed to be nothing a boy could but play football and hope to get a job in the oil fields.

When Fry was 14, his father died, and he stepped up to be the head of the family, working in the oil field in the Summer, and, in the Autumn, quarterbacking the Odessa High School football team, winning a State Championship in 1946. He went on to Baylor University, and was mostly a backup quarterback, graduating in 1951 with a psychology degree.

He returned to Odessa High, taught history, and served on the football coaching staff. In 1952, with the Korean War raging, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. He led the team at the Quantico, Virginia base to the Corps championship and the Poinsettia Bowl. He was discharged with the rank of Captain in 1955.

He returned to Odessa High, and a year later was named head coach. One of his history students would go on to the Hall of Fame -- not College or Pro Football, but Rock and Roll: Roy Orbison.

He was hired as an assistant coach at Baylor in 1959, and the University of Arkansas in 1961. When Arkansas won the Southwest Conference Championship, another SEC school, Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Dallas, hired him as head coach for 1962.

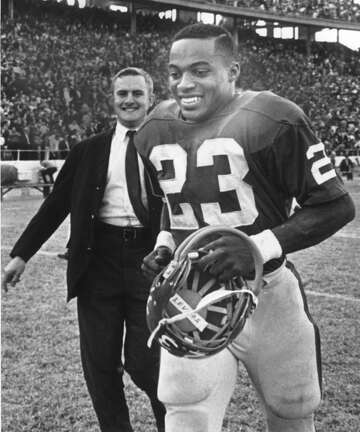

He got the Mustangs to the Sun Bowl in El Paso in his 1st season. He was then named athletic director, and that gave him the authority to desegregate the team. He found the 1st black SMU player in 1966, Jerry LeVias, making him the 1st black player to receive an athletic scholarship from a Southwest Conference school, in any sport.

The way the schedule worked out, though, it was Fry's alma mater, Baylor, who fielded the 1st black varsity player to take the field in the SWC, John Westbrook. On September 10, 1966, Baylor shocked then-Number 7 Syracuse, 35-12. SMU's season opened a week later, on September 17, and they beat Illinois 26-7, a foreshadowing of Fry's later Big 10 success. On November 19, the same day as the famous 10-10 tie between Notre Dame and Michigan State, LeVias' SMU and Westbrook's Baylor played each other at the Cotton Bowl stadium, and SMU won 24-22.

Fry and LeVias at SMU

Fry got SMU an 8-2 record in 1966, and its 1st SWC title in 18 years, with LeVias making the All-Conference team. They lost the Cotton Bowl to Georgia. In 1968, he won his 1st bowl game, the Bluebonnet Bowl in Houston.

That year, LeVias became a 3-time All-American. He would go on to play for the San Diego Chargers (making the AFL All-Star Game as a rookie in 1969) and the Houston Oilers. At 73, he now works in the Houston Texans' front office, and is a member of the College Football and Texas Sports Halls of Fame.

In 1969, Hayden married Shirley Griffin, and they were together for the rest of their lives. The marriage produced 4 sons: Randy, Zach, Kelly and Adrian; and a daughter, Robin. Shirley bought daughter Jayme and son Bryan from her 1st marriage. Hayden lived to see 4 grandchildren and a great-grandchild.

SMU went on a downturn: From 1969 to 1972, they went 3-7, 5-6, 4-7 and 7-4, and Fry was fired. He finished his SMU tenure 49-66-1. Fry would later say that, due to having the 2nd-smallest enrollment in the SWC, some SMU boosters thought they couldn't compete honestly, and wanted to put up a slush fund to pay players, but Fry wouldn't allow it:

For several years some of SMU’s big contributors had been trying to get me to buy players. They wanted me to use their money to recruit illegally, and I wouldn’t do it. Every time I was approached on the matter I told them absolutely no. I believe they used a new president who wasn’t strong enough to stand up to them to get to me.

The boosters convinced the new administration to fire Fry. But he was right: From 1973 to 1986, under head coaches Dave Smith, Ron Meyer and Bobby Collins, SMU got better through the slush fund. Meyer got them to the 1980 Holiday Bowl, but they got caught and were put on probation, so their 1981 team went 10-1 but were ineligible for the SWC title or a bowl game.

In 1982, his 1st season in charge, Collins got the Mustangs to an 11-0-1 record and a Cotton Bowl win. Maybe the team's recent probation stuck in people's minds, because, despite having a slightly better record, they only finished Number 2 in the polls to 11-1 Penn State, where Joe Paterno was said to be running "a clean program." (Little did we then know.)

From 1982 to 1984, Collins' "Pony Express" went 29-3-1 in regular-season play, also winning an Aloha Bowl and losing a Sun Bowl. But they got caught again, and were put on probation. The NCAA told them that if they got caught again, their program would be suspended: It was being called "the death penalty." Bumper stickers began to be seen around Texas, reading, "Support pro football: Watch the SMU Mustangs."

Collins was 6-5 in both 1985 and 1986, ineligible for bowl games... and SMU got caught yet again. The NCAA showed them they weren't bluffing: The 1987 SMU football season was canceled. During the preparations to restore and clean up the program, SMU decided they couldn't be competitive in 1988, either, so they canceled it themselves.

From 1975 to 1986, at the University of Southern Mississippi and SMU, Collins had a record of 91-44-3 -- but we can guess he probably cheated at USM, just as he did at SMU. He is now 86 years old. In the 33 seasons since the cancellation, he has never held another job in college sports. Nor has he held one in any professional football league. When even the XFL (2001 or 2020) won't hire you, you're radioactive.

SMU alumnus and Green Bay Packer legend Forrest Gregg was brought in to be head coach and athletic director. After going 2-9 in 1989 and 1-10 in 1990 -- 0-16 in SWC play -- he remained as AD and hired Tom Rossley as head coach. They went 1-9 in 1991, got up to 5-6 in 1992, but won just 4 games over the next 3 seasons.

When the SWC collapsed in 1996, with Arkansas having left for the Southeastern Conference, and Texas, Texas A&M, Texas Tech and Baylor joining the Big 8 to form the Big 12, SMU joined the Western Athletic Conference. Joining the less-rough WAC didn't help much: A 6-5 season in 1997 under new coach Mike Cavan was their only winning season between 1986 and 2009. But in 2008, switching to the even less-competitive Conference USA helped: Starting in 2009, they went 30-23 and went to 4 straight bowl games, winning 3. Under current coach Sonny Dykes, they were 10-3 this year.

On the field, SMU was better off for having fired Hayden Fry. But the price they paid was too high.

*

In 1973, Hayden Fry was hired as head coach and athletic director at North Texas State University, now the University of North Texas. In his 1st season, he got them a share of the Missouri Valley Conference title. They went 10-1 in 1977 and 9-2 in 1978, but weren't invited to a bowl game -- probably because Fry took them out of the MVC in the hope of joining a bigger conference, but none would take them.

In 1979, he was hired as the head coach at the University of Iowa. They hadn't had a winning season in 17 years, but they still filled Kinnick Stadium in Iowa City for every home game. He knew he had a better chance to go to bowl games, and that he wouldn't have to also be the athletic director: That would be Chalmers "Bump" Elliott, a former Michigan star halfback and head coach who was already a friend of his. (By a sad coincidence, Bump died earlier this month, at age 94.)

Fry and Elliott

Iowa had been 2-9 in 1978. In his 1st game, Iowa lost 30-26 to Indiana, which seemed like progress. In his 2nd game, they went to Oklahoma, then ranked Number 3, and were losing only 7-6 midway through the 4th quarter, but fell apart, losing 21-6. Fry said he would "punch any player in the mouth if he was smiling."

They must have listened. The next week, they hosted Number 7 Nebraska, and lost only 24-21. The week after, he got his 1st win, defeating cross-State rival Iowa State 30-14, starting a 3-game winning streak. They finished 5-6, but fell back to 4-7 in 1980.

But Hayden Fry was changing things at Iowa. He wasn't just changing the program, he was changing the culture. Not the fan support: That was already amazing. Rather, he was changing what it was that they were supporting, into something worthy of that support.

He commissioned a new logo for the Hawkeyes, known as the Tigerhawk, designed by Bill Colbert of Cedar Rapids. Since the Pittsburgh Steelers, winners of 4 recent Super Bowls, also wore black and gold, he asked the Steelers for permission to copy their exact uniform design, and got it. He had stickers affixed to the helmets reading "ANF," for "America Needs Farmers" -- agriculture keeping Iowa alive, and the University letting the country know that farming itself had to be kept alive. He had his players walk onto the field holding hands -- seen as sissy by some, but as solidarity by others.

Fry's (and Colbert's) redesigned Iowa uniform

His Baylor degree having been in psychology, Fry knew that jails and psychiatric wards sometimes painted walls pink to relax and pacify the residents, so he had the visiting team's locker room at Kinnick Stadium painted pink. Michigan coach Bo Schembechler was particularly angered by this, and covered the pink walls with paper.

Fry also assembled a great coaching staff, some of whom would later rebuild other programs as head coaches: Bill Snyder at Kansas State, Bob Stoops at Oklahoma, Mike Stoops at Oklahoma, Barry Alvarez at Wisconsin, and the man who ended up succeeding Fry at Iowa, and is still there, Kirk Ferentz. (Bret Bielema would play at Iowa for Fry, and later, Alvarez would make him an assistant at Wisconsin, and Bielema would succeed him there.)

It took until the 3rd season, 1981, for Iowa to have a winning season under Fry. But it was more than that. Up until then, the joke was that the Big Ten Conference (often written as "Big 10") was really "The Big Two and the Little Eight": From 1968 to 1980, of the 13 Big 10 titles, either Ohio State or Michigan won it every year. The only breakthrough came in 1978, when Michigan State tied Michigan for the title, and beat Michigan in Ann Arbor to win what should have been a tiebreaker, except they were already on probation, eligible for the Conference's title but not its Rose Bowl berth.

Today, the University of Iowa vs. the Unviersity of Nebraska is considered a rivalry. The States border each other, and both are in the Big 10. But back then, Nebraska was in the Big 8, and they didn't play each other every year. This was a good thing, since Nebraska had become a dominant team in college football, and Iowa hadn't. In 1980, Nebraska beat Iowa 57-0. But Iowa opened the 1981 season by beating the Cornhuskers, then ranked Number 7, 10-7, a 60-point swing.

Iowa lost their next game, to in-State rival Iowa State, but followed that by beating Number 6 UCLA. The Hawkeyes were on their way, following this with wins over Northwestern and Indiana. On October 17, they went to Number 5 Michigan and didn't score a touchdown -- but beat them, 9-7. Losses to Minnesota and Illinois hurt them, but nobody else seemed to want to win the Big 10, and they beat Purdue, Wisconsin and Michigan State.

The last of these came on November 21, allowing them to tie Ohio State for the title, the 1st time they'd even shared the title since 1960. Since Ohio State had gone to the Rose Bowl more recently, Iowa got the Rose Bowl berth, but lost to the University of Washington.

The 1982 season got off to an 0-2 start, but Iowa rebounded to earn a Peach Bowl berth, and their win over Tennessee was their 1st bowl game win in 23 years. In 1983, they went 9-2 and got to the Gator Bowl, but lost to Florida. An injury plague struck near the end of the 1984 season, causing an 0-2-1 finish, which they followed with a win over Texas in the Freedom Bowl, 55-17. Quarterback Chuck Long engineered an offense that scored the most points the Longhorns had allowed in a single game in 80 years.

Long and the Hawks were just getting warmed up. They began the 1985 season ranked Number 5, and beat Drake (also an Iowa school, in Des Moines) 58-0. They beat Northern Illinois 48-20 and Iowa State 57-3. They had risen to the nation's Number 1 ranking.

It was at this point that ABC broadcaster Keith Jackson -- whose Georgia accent made Iowa's team name sound like "the Huckeyes" -- could have used an expression I heard him use years later: "The social portion of the Big 10 schedule is over. From here on in, it's strictly meat and potatoes."

Fry and his Hawkeyes did not flinch: They beat Michigan State 35-31, and went to Wisconsin and beat them 23-13. On October 19, Number 1 Iowa hosted Number 2 Michigan on CBS, and won 12-10 thanks to 4 field goals by Rob Houghtlin, one on the last play of the game. Since the rest of the Big 10 hates Michigan, everybody else was grateful to the Hawkeyes.

They followed this with a 49-10 win at Northwestern. But then they faltered, losing 22-13 at Number 8 Ohio State. It would be their only regular-season loss: They beat Illinois 59-0, won away to Purdue 27-24, and won the Floyd of Rosedale trophy by beating Minnesota 31-9.

For the 2nd time in 5 years, Hayden Fry had led Iowa to the Big 10 Championship, their 1st outright win since 1958. They went to the Rose Bowl, but lost 45-28 to UCLA. In a very close vote, quarterback Chuck Long finished 2nd for the Heisman Trophy to Auburn running back Bo Jackson. (This matched the aforementioned 1958 season, in which Iowa quarterback Randy Duncan finished 2nd to Army running back Pete Dawkins. No Iowa player has ever won the Heisman.

Chuck Long

Long may have been born in Norman, Oklahoma, seat of one of the greatest college football programs; and he may have grown up in Wheaton, Illinois, hometown of one of the all-time football greats, Illinois and Chicago Bears legend Red Grange; but he turned both Oklahoma and Illinois down for Iowa. He played for the Detroit Lions from 1986 to 1991, except for 1990 with the Los Angeles Rams. He later coached under Fry at Iowa, and under Bob Stoops at Oklahoma, and was San Diego State's head coach from 2006 to 2008. He is now on the staff of the XFL's St. Louis BattleHawks, and is an analyst for the Big Ten Network.

In 1986, Iowa went 8-3, and beat San Diego State in the Holiday Bowl, despite the game being played at SDSU's home field, Jack Murphy Stadium. In 1987, Iowa went 9-3, and returned to the Holiday Bowl, beating Wyoming.

*

In his book Big Ten Country, Bob Wood, a history teacher and Michigan State graduate, wrote of going to a game at each of the Big 10 Conference schools in the 1988 season, which was also Iowa football's 100th Anniversary season. Wood had just published Dodger Dogs to Fenway Franks, his story of going to all 26 Major League Baseball parks in one season, so when he contacted the University press office The night before his Iowa game, he attended an I-Club dinner at which Fry spoke, and told the story of the Stoops family and its connection to Iowa.

Ron Stoops was the head coach at Cardinal Mooney High School in Youngstown, Ohio. He and his wife Evelyn, a.k.a. Dee Dee, had 4 sons, all of whom played football for him: Ron Jr., Bob, Mike and Mark. Ron Sr. was impressed by Fry, and all 4 of his sons went to Iowa to play. All 4 wore the same number, 41. Every weekend, Ron Sr. would coach Mooney on a Friday night, then packed and drove all night to see his son(s) play for Iowa. And all 4 sons went into coaching.

Earlier in that 1988 season, Ron Sr. and Ron Jr. were coaching against each other. Mooney won in overtime. It must have been too much for the old man, because he had a heart attack and died. At the funeral, someone walked in with an Iowa jersey, Number 41. The sons propped their father up in his coffin, and put the jersey on him. Bob had 2 Big 10 Championship rings, and put one on his father's finger. Dee Dee leaned over to her husband and said, "Now, you'll always be warm."

Fry concluded the story by telling the I-Club, "I told you this because I wanted you to know there are a lot of people out there who love Iowa football." According to Wood, Fry's story got a standing ovation, Fry stayed to shake hands, and was the last one out the door.

It was a weird season for Iowa, as they finished with 6 wins, 4 losses and 3 ties, their only Conference loss a 45-34 shootout at Indiana. Their other 2 regular-season losses, to Hawaii and Colorado, were each by a field goal. As in 1985, they had a nationally televised showdown with Michigan in Iowa City in mid-October, and it ended 17-17. It was the only blot on Michigan's Conference record, so, had Iowa gotten so much as 1 more field goal in that game, they would have won the Big 10 again. They ended up losing the Peach Bowl to North Carolina State.

They were just 5-6 in 1989, but won 7 of their 1st 8 in 1990, with only a non-conference loss away to then-Number 10 Miami disturbing their record. They beat both Michigan teams and Illinois away. Then they lost at home to Ohio State. On the final day, Michigan beat Ohio State, clinching at least a share of the Big 10 title for Iowa, but they lost away to arch-rival Minnesota, 31-24, forcing a rare 4-way tie for the title between Iowa, Michigan, Michigan State and Illinois. Iowa had the tiebreakers to get the Rose Bowl berth, and trailed Washington 33-8 at the half before a comeback fell short, 46-34. Fry had now gotten them 3 Big 10 titles in 10 seasons, but they'd lost the Rose Bowl every time.

They should have won the whole thing in 1991, but a home loss to Michigan cost them the Big 10 title. They were 10-1 before finishing with a tie against Brigham Young in the Holiday Bowl. By this point, Fry was becoming a victim of his own success, as his assistants began to get better offers, head coaching jobs, and assistants' jobs at bigger schools. Iowa finished only 5-7 in 1992, and started 1993 only 2-5 before making it 6-5, getting them into the Alamo Bowl, where they lost to the University of California.

Ironically, 1993 was the year on Coach when Hayden Fox got his Minnesota State team into a de facto National Championship Game. Before the show's writers knew where Iowa, Kemp's alma mater, would play their bowl game, or even if they would get into one, they wrote Minnesota State's destination as the Pioneer Bowl -- at the Alamodome in San Antonio.

(The writers, Judd Pillot and John Peaslee, eventually wrote 4 bowl games for Fox's Screaming Eagles, all starting with P like their own names: The 1991 Pineapple Bowl in Honolulu, which Minnesota State won over equally fictional South Texas; the 1992 Patriot Bowl in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, which they lost to Iowa 71-7 in a blizzard following a flu outbreak; the 1993 Pioneer Bowl in San Antonio, which they won over fictional West Texas to win the National Championship, which Florida State won in real life that season; and the 1994 Popcorn Bowl in Los Angeles, which they lost to a real school, but I've forgotten which one.)

Iowa finished 5-5-1 in 1994, and, as Fry was now 65, people began to wonder if the end was near. Not just yet: In 1995, they went 704 and then won the Sun Bowl in El Paso, in Fry's native Texas, beating Washington, who had beaten him in 2 of his Rose Bowls. They went 8-3 in 1996, and went back to the Alamo Bowl, beating Texas Tech 27-0.

Now, the opposite feeling took hold, that Fry might coach and win at Iowa indefinitely. But this also turned out to be untrue. They went 7-4, losing by 4 points away to Michigan, by 3 away 2 Wisconsin (the Badgers' 1st win ever over Fry), and by 1 away to a resurgent Northwestern. (Only a 23-7 loss away to Number 7 Ohio State was a bad one.) They lost the Sun Bowl to Arizona State.

In 1998, Fry developed prostate cancer. His mind, fairly, was not fully on his work, and he finished 3-8, including his 1st loss to Iowa State in 15 years. On November 21, he lost to Minnesota 49-7 at the Metrodome, and announced his retirement the next day, after 20 seasons in Iowa City. Assistant coach Kirk Ferentz succeeded him, and has now surpassed him as Iowa's longest-lasting and winningest coach.

Fry outlasted the TV show Coach, which was canceled in 1997. However, the fictional Hayden Fox had done something that the real Hayden Fry had not done: He had gotten an NFL head coaching job, with a fictional expansion team, the Orlando Breakers. After an awful 1st season at 1-15, Fox got them into the Playoffs in 1996, but, mirroring Minnesota State's flu-and-snow-aided Patriot Bowl beatdown, the team came down with food poisoning and lost badly to the Buffalo Bills. Fox then retired, while Fry coached 2 more seasons.

Fry was 143-89-6 at Iowa, including 96-61-5 in Big 10 play; and 232-178-10 overall, in 37 consecutive seasons as a head coach. He won 3 Conference Championships, and coached in 17 bowl games, winning 7 of them. In 2003, he was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame -- along with Jerry LeVias, whom he'd made the 1st black scholarship athlete in the Southwest Conference.

In 2009, First Avenue in Coralville, Iowa, which leads from Interstate 80 to the University of Iowa campus, was renamed Hayden Fry Way. A state of him was erected along the street.

At his statue's dedication

But his cancer returned, and on December 17, 2019, Hayden Fry died at age 90. He was successful, and, as football people in his native Texas found out -- to the dismay of some of them -- he was incorruptible. He turned Iowa football from a native institution but a regional, never mind national, afterthought into something admired from coast to coast.

As was he.

1 comment:

Iowa's Nile Kinnick, for whom the Hawkeyes stadium is named, won the Heisman in 1939.

Post a Comment