Top 10 Athletes From Iowa

Dishonorable Mention to Adrian Constantine "Cap" Anson of Marshalltown. In 27 seasons of professional baseball, the 1st baseman had a .334 lifetime batting average, and was the 1st man to have over 3,000 hits, and the 1st to have over 2,000 runs batted in. He led the National League in batting twice and in RBIs 8 times.

As a manager, he led the Chicago White Stockings (forerunners of the Cubs) to Pennants in 1880, 1881, 1882, 1885 and 1886. He was still a regular player in 1897, at the age of 45. And, before the 1886 season, he took his players down to Hot Springs, Arkansas to "boil the beer out of them." Thus did Cap Anson invent Spring Training. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939, in one of its earliest classes.

So, why "Dishonorable"? Because he is widely believed to be the reason that black men were excluded from professional baseball from 1888 to 1945. In 1883, he refused to play an exhibition game in Toledo in which a black player, Moses Walker, was in the lineup for the local team. He was told that this would result in his forfeiting the game and his team's (and thus his) share of the gate receipts, and he backed down. In 1887, he refused to allow George Stovey to play for Newark against his White Stockings in an exhibition game in Newark, and Stovey did not play.

Shortly thereafter, black players "disappeared" from professional baseball, in what became known as the "gentlemen's agreement." It stood long past Anson's 1897 retirement and his 1922 death, until Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson in 1945 and promoted him to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

How responsible for this was Anson? He was the biggest star in the game. If White Stockings owner Al Spalding was, in effect, the commissioner of baseball, then Anson was Michael Jordan to Spalding's David Stern: Whatever Anson wanted, Spalding approved, and Spalding's word was law. But Spalding never gets the blame for this, because he was never heard saying, "Get that (N-word) off the field!" Anson was.

It can, of course, be argued that the color line would have been drawn even without Anson's objection. But, more than anyone else in the story of what actually happened, he is to blame.

Honorable Mention to Shawn Johnson of West Des Moines. In 2008, she won the Gold Medal in the balance beam at the Olympics in Beijing, and received the James M. Sullivan Award as America's outstanding amateur athlete.

10. Dave Bancroft of Sioux City. "Beauty" was the rookie shortstop on the Philadelphia Phillies team that won the 1915 National League Pennant. He also won Pennants with the New York Giants in 1921, 1922 and 1923, winning the World Series in 1921 and 1922. That said, he is often considered one of the less-deserving members of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He is one of the "Frisch Five," elected by the Veterans Committee on the say-so of his former Giant double-play partner, Frankie Frisch, a member of that committee. Nevertheless, he is in the Hall.

9. Jay Berwanger of Dubuque. The University of Chicago dropped big-time sports only a few years after his 1935 season there, in which he was named the 1st winner of what would later be renamed the Heisman Trophy. He was also a decathlete on their track team.

The 1st NFL Draft was held in 1936, and he was the 1st player, selected, by the Philadelphia Eagles. He wanted $1,000 per game -- which, with inflation factored in, would be about $286,000 for an annual salary. That doesn't sound like much by today's standards, does it? But it was the Great Depression, and the Eagles weren't exactly swimming in cash.

They traded his rights to the Chicago Bears. He didn't sign, because he thought he had a chance to be the U.S.' representative in the decathlon at the 1936 Olympics. But he didn't make it. He asked Bears owner-coach George Halas for $15,000 for the season (about $266,000), and Halas -- famously cheap, later described by Mike Ditka as a man who "throws nickels around like manhole covers" -- offered $13,500 (about $239,000). Berwanger turned it down, took a job with a rubber company, and another as an assistant coach at his alma mater. He later said he should have taken Halas' offer.

Without him, the Bears reached 6 of the next 11 NFL Championship Games, winning 4. Without them, Berwanger lived a long and professionally successful life, but was rarely in the spotlight, always coming back into it in December as another Heisman was awarded. He was elected to both the Iowa and the Chicagoland Sports Halls of Fame.

8. Elmer Layden of Davenport. A fullback, he was one of the "Four Horsemen of Notre Dame," helping the Fighting Irish win the 1924 National Championship. His pro career wasn't much, playing in 1925 for the Hartford Blues and in 1926 for the Rock Island Independents and, along with his college teammate Harry Stuhldreher (but not the other 2, Jim Crowley and Don Miller), for a team named for them, the Brooklyn Horsemen.

He later coached at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh and at Notre Dame, with a career record of 103-34-11. He also served as Notre Dame's athletic director, and was Commissioner of the NFL from 1941 to 1946. He was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame.

He later coached at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh and at Notre Dame, with a career record of 103-34-11. He also served as Notre Dame's athletic director, and was Commissioner of the NFL from 1941 to 1946. He was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame.

7. Nile Kinnick of Adel. Born in the same State in the same year as Bob Feller, he could have become an even bigger star. He won the Heisman Trophy at the University of Iowa in 1939, and won the Associated Press' Male Athlete of the Year. He went to law school rather than play in the NFL, and there was talk that he would be Governor of Iowa and eventually President of the United States.

World War II prevented that. On June 2, 1943, Ensign Nile Kinnick was unable to land his Grumman F4F Wildcat on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Lexington, and crashed off the coast of Venezuela. His body was never recovered. He was only 24, matching his Iowa uniform number, which was retired. Of the 82 men who have been awarded the Heisman, he is the only one to die in military service, and only Ernie Davis (1961, Syracuse University) had a shorter life.

In 1972, Iowa Stadium was renamed Kinnick Stadium. He was posthumously elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951, in the same class as Layden.

6. Urban "Red" Faber of Cascade. A member of the 1917 World Champion Chicago White Sox, he was also with them in 1919 when 8 of their players were accused of throwing the World Series, but, as far as anybody knows, he was clean. In spite of the team having been broken up in the resulting Black Sox Scandal, he led the American League in earned run average in 1921 and 1922, and finished his career with a record of 254-213. He lived long enough to see himself elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

5. Fred Clarke of Des Moines. A left fielder, he starred for the Louisville Colonels and then, after they were consolidated with the Pittsburgh Pirates after the 1899 season, for the Pirates. From 1897 to 1915, he was a player-manager, but still managed to bat .312, collecting 2,678 hits and 506 stole bases. He managed the Pirates to National League Pennants in 1901, 1902, 1903 and 1909, losing the 1st World Series in 1903, but winning it in 1909. He lived long enough to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

4. Kurt Warner of Cedar Rapids. One of football's biggest "rags to riches" tales, the former University of Northern Iowa quarterback had washed out with the Green Bay Packers in 1994, and was playing arena football in his home State and worked in a supermarket when the St. Louis Rams offered him a lifeline in 1998.

World War II prevented that. On June 2, 1943, Ensign Nile Kinnick was unable to land his Grumman F4F Wildcat on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Lexington, and crashed off the coast of Venezuela. His body was never recovered. He was only 24, matching his Iowa uniform number, which was retired. Of the 82 men who have been awarded the Heisman, he is the only one to die in military service, and only Ernie Davis (1961, Syracuse University) had a shorter life.

In 1972, Iowa Stadium was renamed Kinnick Stadium. He was posthumously elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951, in the same class as Layden.

6. Urban "Red" Faber of Cascade. A member of the 1917 World Champion Chicago White Sox, he was also with them in 1919 when 8 of their players were accused of throwing the World Series, but, as far as anybody knows, he was clean. In spite of the team having been broken up in the resulting Black Sox Scandal, he led the American League in earned run average in 1921 and 1922, and finished his career with a record of 254-213. He lived long enough to see himself elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

5. Fred Clarke of Des Moines. A left fielder, he starred for the Louisville Colonels and then, after they were consolidated with the Pittsburgh Pirates after the 1899 season, for the Pirates. From 1897 to 1915, he was a player-manager, but still managed to bat .312, collecting 2,678 hits and 506 stole bases. He managed the Pirates to National League Pennants in 1901, 1902, 1903 and 1909, losing the 1st World Series in 1903, but winning it in 1909. He lived long enough to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

4. Kurt Warner of Cedar Rapids. One of football's biggest "rags to riches" tales, the former University of Northern Iowa quarterback had washed out with the Green Bay Packers in 1994, and was playing arena football in his home State and worked in a supermarket when the St. Louis Rams offered him a lifeline in 1998.

An injury to Trent Green in the 1999 preseason was Warner's chance, and he led the Rams all the way to victory in Super Bowl XXXIV -- the 1st NFL Championship in St. Louis history, and the 1st for the Rams franchise in 48 years. He was named Most Valuable Player of that game, and would be named NFL MVP in 1999 and 2001.

A 4-time Pro Bowler, he would get the Rams into Super Bowl XXXVI, but they lost. He would later be signed by the Arizona Cardinals, and get them into Super Bowl XLIII, their 1st NFC Championship, and their 1st NFL Championship Game under any name in 60 years. But they lost, too.

He was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame earlier this year. He was elected to the St. Louis Football Ring of Fame and the Arizona Cardinals Ring of Honor. If the Rams institute a new team hall of fame once their permanent Los Angeles (Inglewood) stadium opens, he might be named to it, even though he never played a professional game in the L.A. metropolitan area.

3. Roger Craig of Davenport. Not to be confused with the 1950s and '60s baseball pitcher of the same name, this Roger Craig starred in both football and track at the University of Nebraska. A 4-time Pro Bowler, he helped the San Francisco 49ers win Super Bowls XIX, XXIII and XXIV. In 1985, he became the 1st running back with 1,000 yards in both rushing and receiving. He was named NFL Offensive Player of the Year in 1988.

He rushed for 8,189 yards, and also caught 566 passes for 4,911 yards, totaling 73 touchdowns. He has been named to the NFL's 1980s All-Decade Team, the 49ers Hall of Fame, and the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame -- but, for some strange reason, not yet the Pro Football Hall of Fame. This makes no sense: Despite the State having produced a Super Bowl-winning quarterback, 2 Heisman Trophy winners, and one of Notre Dame's Four Horsemen, he is the most accomplished football player from Iowa.

2. Dan Gable of Waterloo. He is the greatest wrestler who ever lived, and the greatest wrestling coach who ever lived, and you can take all your WWE stars and stick them where the Sun don't shine.

At Waterloo West High School, his career record as a wrestler was 64-0, winning 3 State Championships. He was also a State Champion swimmer, their quarterback, and a baseball player. At Iowa State University, he went 181-1, winning 2 National Championships, losing only in the NCAA Final in his senior year. In other words, he won 225 amateur wrestling matches before he was finally beaten.

The Soviet Union athletic machine, rightly proud of their wrestling achievements, vowed to "scour the Eastern Bloc to find a wrestler who could take down Dan Gable." They were unsuccessful: Despite an injured knee and stitches in his head after an injury in his 1st match, he won the Gold Medal in the 150-pound weight class at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, without surrendering a single point in any match.

If I were counting his coaching achievements, he would easily be Number 1. Despite having been an Iowa State graduate, he went to their arch-rivals, the University of Iowa, in 1976. He won 9 straight National Championships from 1978 to 1986, finally being dethroned in 1987 by... Iowa State.

He coached until 1997, with a dual meet record of 355-21-5, 16 team National Championships, 152 All-Americans, 45 individual National Champions, and 4 Olympic Gold Medalists. He also coached the U.S. Olympic team in 1980 (boycotted), 1984 and 2000. He also, literally, wrote the book on coaching the sport: Coaching Wrestling Successfully, published in 1999. Of course, he is in the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. He should be: He is both the Babe Ruth and the Casey Stengel of his sport.

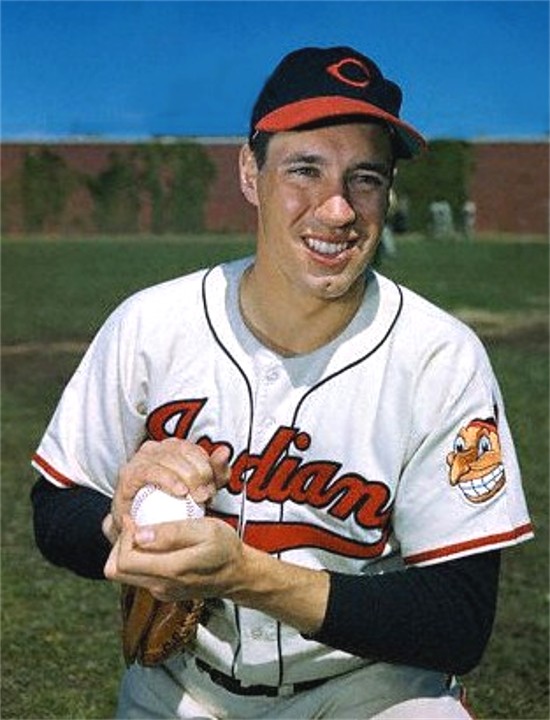

1. Bob Feller of Van Meter. He had one of the best curveballs ever, but his stock in trade was the fastball, a.k.a. the heater. So he was known as Bullet Bob, Rapid Robert, and the Heater From Van Meter. And he might have been the best pitcher of his generation.

At Waterloo West High School, his career record as a wrestler was 64-0, winning 3 State Championships. He was also a State Champion swimmer, their quarterback, and a baseball player. At Iowa State University, he went 181-1, winning 2 National Championships, losing only in the NCAA Final in his senior year. In other words, he won 225 amateur wrestling matches before he was finally beaten.

The Soviet Union athletic machine, rightly proud of their wrestling achievements, vowed to "scour the Eastern Bloc to find a wrestler who could take down Dan Gable." They were unsuccessful: Despite an injured knee and stitches in his head after an injury in his 1st match, he won the Gold Medal in the 150-pound weight class at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, without surrendering a single point in any match.

If I were counting his coaching achievements, he would easily be Number 1. Despite having been an Iowa State graduate, he went to their arch-rivals, the University of Iowa, in 1976. He won 9 straight National Championships from 1978 to 1986, finally being dethroned in 1987 by... Iowa State.

He coached until 1997, with a dual meet record of 355-21-5, 16 team National Championships, 152 All-Americans, 45 individual National Champions, and 4 Olympic Gold Medalists. He also coached the U.S. Olympic team in 1980 (boycotted), 1984 and 2000. He also, literally, wrote the book on coaching the sport: Coaching Wrestling Successfully, published in 1999. Of course, he is in the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. He should be: He is both the Babe Ruth and the Casey Stengel of his sport.

1. Bob Feller of Van Meter. He had one of the best curveballs ever, but his stock in trade was the fastball, a.k.a. the heater. So he was known as Bullet Bob, Rapid Robert, and the Heater From Van Meter. And he might have been the best pitcher of his generation.

And he beat his generation to the major leagues. In their 1981 book The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time, Lawrence Ritter and Donald Honig (one of them, anyway, but it's hard to tell which) wrote, "Bob Feller remains baseball's only prodigy." He debuted for the Cleveland Indians in 1936, while still in high school. To give you an idea: Joe DiMaggio also debuted in 1936, but he was 4 years older; Ted Williams was also born in 1918, but debuted 3 years later.

He set an American League record, striking out 17 batters in a game -- when 17 was also his age. In 1938, still not quite 19, he raised that record to 18. In 1940, he pitched a no-hitter, still the only one ever pitched on a season's Opening Day. he won the pitching Triple Crown that season, including 27 wins, a total only 1 American League pitcher has topped since (Denny McLain's 31 in 1968).

At the close of the 1941 season, just before turning 23, he was 107-54. For the sake of comparison: Warren Spahn, also decorated for heroism in World War II, wouldn't win his 1st major league game until he got back -- at age 25.

Feller missed the entire seasons of 1942, 1943 and 1944, and most of 1945 -- at the ages of 23, 24, 25 and 26 -- serving in the U.S. Navy, into which he was sworn by former Heavyweight Champion, Commander Gene Tunney. He served as a gunner on the battleship USS Alabama, and rose to the rank of Chief Petty Officer.

"Hooyah!"

He said he didn't care what statistics or achievements he lost due to his wartime service, because The War was more important. He also had some words of wisdom for people who compare sports and war: "Anybody who says sports is war has never been in a war."

In 1946, his 1st full season back, he pitched a no-hitter against the Yankees, and struck out 348 batters. This was long believed to be a major league record, but a later check revealed that Rube Waddell, had 349 strikeouts in 1904, not 343 as previously believed. It was still the highest total between 1904 and 1965. In 1948, he finally won an AL Pennant and a World Series with the Indians. In 1951, he pitched a 3rd no-hitter, tying what was then the record.

He was an 8-time All-Star. There was no Cy Young Award in his era, but if there was, he probably would have won it 5 and possibly 7 times. As it is, he finished in the top 3 in the AL MVP voting 3 times. He won another Pennant in 1954, but all those early innings finally wore him down, and he retired after the 1956 season.

His final record was 266-162, with 2,581 strikeouts. Had he been exempted from service, and not gotten hurt in the meantime, he might have won over 350 games, and seriously challenged the career record for strikeouts at the time, Walter Johnson's 3,508.

He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his 1st year of eligibility. In 1999, The Sporting News ranked him 36th on their 100 Greatest Baseball Players. The Indians retired his Number 19, and he lived long enough to see a statue of himself dedicated outside their current ballpark, what's now named Progressive Field. There is a Bob Feller Museum in Van Meter, whose architect was his son Stephen Feller.

No comments:

Post a Comment