For some teams, determining the greatest player in their history is hard, because there's more than one good choice. If you're a Baltimore Orioles fan, it could be Brooks Robinson, or Cal Ripken Jr. For the Pittsburgh Pirates, Honus Wagner or Roberto Clemente.

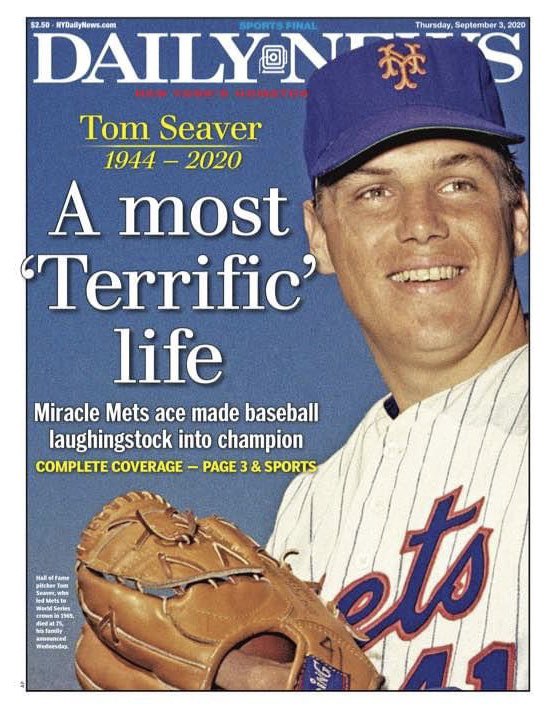

For the New York Mets, there is only one: Tom Seaver.

George Thomas Seaver was born on November 17, 1944 in Fresno, California. He starred in both baseball and basketball at Fresno High School. Other noted graduates include another Pennant-winning Mets pitcher, Bobby Jones; Jim Maloney, who pitched a no-hitter against the Mets; Monte Pearson, who pitched a no-hitter for the Yankees against the Boston Red Sox; Pat Corrales, former major league catcher and manager; Hall of Fame Los Angeles Rams linebacker Les Richter; plus Cher, author William Saroyan, Ross Bagdasarian (a.ka. David Seville, creator of The Chipmunks), Mannix actor Mike Connors, and antiwar activist David Harris, ex-husband of singer Joan Baez.

Upon graduation, Seaver enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, serving on active duty for a year, before enrolling at Fresno City College, and, after a year, earned a scholarship to the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles.

Tommy Lasorda, himself a former pitcher and later the Hall of Fame manager for the Los Angeles Dodgers, scouted Seaver for the Dodgers. He wrote, "Plenty of desire to pitch and wants to beat you." In the 1st-ever Major League Baseball Draft, on June 8, 1965, the Dodgers selected Seaver.

He could have been the successor to Sandy Koufax, and pitched alongside Don Drysdale in the short term and Don Sutton in the long term. But he asked for a signing bonus of $70,000, and the Dodgers, owned by Walter O'Malley, turned him down. It was the 1st time Seaver dealt with a notorious baseball cheapskate. It would not be the last.

In January 1966, the Atlanta Braves selected Seaver in a secondary draft, and he signed with them. He could have been a teammate of Hank Aaron and Phil Niekro. But USC had played 2 exhibition games, neither of which he had appeared in, so Commissioner William "Spike" Eckert voided the contract. And because he had signed the contract anyway, the NCAA ruled him a professional, and therefore ineligible to continue playing college baseball.

Charles Seaver, Tom's father, wrote to Eckert, threatening a lawsuit. Eckert's solution was to rule that other teams could match the Braves' offer. Three teams were willing to do so, and on April 2, 1966, their names were put in a hat. Eckert pulled on the slip of paper with the name of the New York Mets. The other 2 were the Philadelphia Phillies (he could have been a teammate of Mike Schmidt and Steve Carlton) and the Cleveland Indians (he could have been on a staff with Sam McDowell and Luis Tiant and, later, Gaylord Perry).

*

He made his major league debut for the Mets on April 13, 1967. A mere 5,005 fans came out on a Thursday afternoon to see the Mets play the Pittsburgh Pirates at Shea Stadium. Wearing Number 41, the only number he would wear in his 20 seasons in the majors, Seaver started against Woodie Fryman, went 5 1/3rd innings, struck out 8, but walked 4, allowing 6 hits and 2 runs, and did not factor in the decision.

Chuck Hiller drove in all the Met runs with a home run and an 8th-inning double, and the Mets won, 3-2. The winning pitcher was Chuck Estrada, and Ron Taylor got the save. (Taylor had won the 1964 World Series with the St. Louis Cardinals, so he was the only member of the '69 Mets who already had a ring.)

Seaver drew a walk in the 2nd inning in his 1st plate appearance, and singled in the 4th in his 1st official at-bat. He remained a good hitter for a pitcher, batting just .154, but hitting 12 home runs.

He was named to the All-Star Game at Anaheim Stadium as a rookie. It turned out to be the 1st of 12 All-Star Games for him. Before the game, he approached Aaron, and asked him for his autograph. Aaron said, "Kid, I know who you are, and before your career is over, I guarantee you, everyone in this stadium will, too." Aaron would later call Seaver the toughest pitcher he ever faced.

That game also turned out to be the longest All-Star Game ever to that point, going 15 innings, and when Tony Perez of the Cincinnati Reds hit a home run to make it 2-1 to the National League in the top of the 15th, Seaver pitched a scoreless bottom half of the inning to earn the save. He went 16-13 that season, with a 2.76 earned run average, and was named the NL Rookie of the Year.

In 1968, new Mets manager Gil Hodges named him the Opening Day starter. He won 16 games, and was a reason for Met fans to hope. But they only finished 9th, only the 2nd time they hadn't finished 10th and last in the single-division NL since their founding in 1962.

At the 1968 All-Star Game at the Astrodome in Houston, Seaver had his one and only faceoff with Mickey Mantle of the Yankees. Mantle fouled a pitch off, and swung and missed at 3 others, striking out. He was done. Seaver was just getting warmed up.

The 1969 season was the 1st of Divisional Play. The Mets were put in the NL Eastern Division, along with the Chicago Cubs, the Philadelphia Phillies, the Pittsburgh Pirates, the St. Louis Cardinals, and the expansion Montreal Expos.

This time, something was happening. The team became known as the Miracle Mets. It was, as New York Post baseball writer Leonard Schuster said, as if 7 years of bad luck were all being evened out in Year 8. Seaver went 25-7, earning the NL's Cy Young Award, and finished 2nd in the NL's Most Valuable Player voting to Willie McCovey of the San Francisco Giants.

To this day, no player has ever won the MVP in a Met uniform. McCovey had a great season at the bat, but the Giants just missed the NL Western Division title, and there can be no serious argument that McCovey was a more valuable player to his team than Seaver was to his. No player has ever been more valuable to the Mets in any season than Seaver was in 1969. Their top hitter was Tommie Agee, and he topped out at 26 home runs and 76 RBIs.

For most of the season, the Mets were in 2nd place in the NL East, behind the Cubs. On July 9, over 50,000 were on hand at Shea to see Seaver take a perfect game into the 9th inning against the Cubs. Jim Qualls, a backup outfielder, broke it up with a single to left with 2 outs to go.

But the message had been sent: The Mets are coming. They overtook the Cubs in early September, and clinched the Division at home on September 24. In Game 1 of the NL Championship Series, the 1st postseason game in Met history, Seaver outpitched Niekro, and the Mets ended up sweeping the Braves, again clinching at home, on October 6.

Seaver lost Game 1 of the World Series to the Baltimore Orioles, but went the distance (10 innings) to win Game 4, aided by Ron Swoboda's fantastic catch of a drive by Brooks Robinson. The next day, October 16, 1969, the Mets clinched at Shea, taking all 3 clinchers at home.

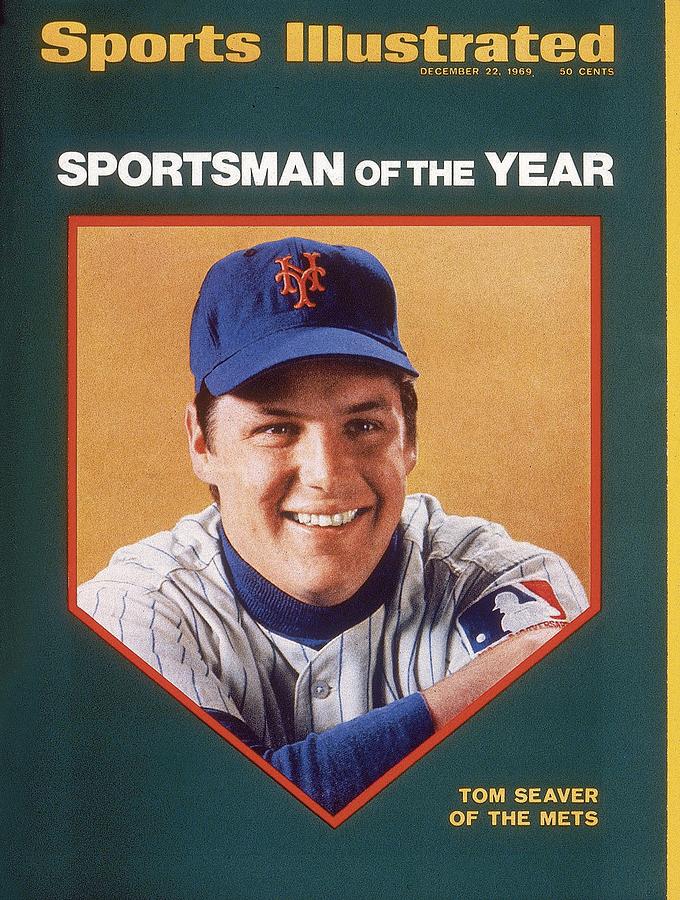

The Hickock Belt for the top professional athlete of the year was given out from 1950 to 1976, and Seaver received it for 1969. And Sports Illustrated named him their Sportsman of the Year.

Other baseball players to receive the Hickok Belt: Yankees Phil Rizzuto in 1950, Allie Reynolds in 1951, Mickey Mantle in 1956, Bob Turley in 1958, and Roger Maris in 1961; plus Willie Mays of the New York Giants in 1954, Maury Wills of the Dodgers in 1962, Sandy Koufax of the Dodgers in 1963 and 1965, Frank Robinson of the Orioles in 1966, Carl Yastrzemski of the Red Sox in 1967, Brooks Robinson of the Orioles in 1970, Steve Carlton of the Phillies in 1972, and Pete Rose of the Reds in 1975.

Other baseball players to receive SI's award, first given with the magazine's founding in 1954 and now named Sportsperson of the Year: Johnny Podres of the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1955, Stan Musial of the Cardinals in 1957, Koufax in 1965, Yastrzemski in 1967, Rose in 1975, Willie Stargell of the Pirates in 1979, Dale Murphy of the Braves in 1987, Orel Hershiser of the Dodgers in 1988, Cal Ripken of the Orioles in 1995, Mark McGwire of the Cardinals and Sammy Sosa of the Cubs in 1998 (now a tainted award), Curt Schilling and Randy Johnson of the Arizona Diamondbacks in 2001 (ditto), collectively the Red Sox in 2004 (ditto), Derek Jeter of the Yankees in 2009, Madison Bumgarner of the Giants in 2014 (the last 2, still legit), and Jose Altuve of the Houston Astros in 2017 (tainted).

And yet, having reached a point where he owned New York -- or, at least, shared it with the Jets' Joe Namath -- Seaver, still officially in the Marine Corps Reserve, publicly opposed the Vietnam War: "It’s perfectly ridiculous what we’re doing about the Vietnam situation. It’s absurd! When the series is over, I’m going to have a talk with Ted Kennedy, convey some of my ideas to him and then take an ad in the paper. I feel very strongly about this.”

Seaver also said, "If the Mets can win the World Series, we can get out of Vietnam." This was echoed by Mets outfielder Art Shamsky: In his book After the Miracle: The Lasting Brotherhood of the '69 Mets, he wrote, "We were a part of something so special in 1969. The common thinking then was, 'If the Mets can win the World Series, then anything is possible.'"

*

Seaver became known as "Tom Terrific" and, reflecting his importance to the Mets, "The Franchise." No longer was Roger Bannister, who wore it on his jersey when he became the 1st man to run a sub-4-minute mile in 1954, the athlete most identified with the Number 41: Seaver, winning a World Series in New York, is forever the man of whom the number reminds Americans.

He became known for his overhand delivery, known as "drop and drive," with his right knee touching the ground. On April 22, 1970, at Shea, he used that delivery to strike out a record-tying 19 batters (that record has since been surpassed), including a new record of 10 straight (that record has not), the last 10 of the game, against the San Diego Padres. In 1971, he won his 2nd Cy Young Award.

He was a thinking man's pitcher: Although he had a good fastball, it wasn't overwhelming, and he knew enough to compensate for this by developing an array of pitches that, when mixed together, made him very hard to hit. One time, he was pitching to McCovey, and having a hard time with him, and finally struck him out.

His catcher, Jerry Grote, said as they walked off, "What the hell was that?'

Seaver: "Changeup, Grote."

Grote: "But you don't throw one."

Seaver: "I do now, big boy!"

Cleon Jones, the left fielder whose .340 batting average on the '69 team would remain a Met record for 29 years, said, "He's the kind of man you'd want your kids to grow up to be like. Tom's a studious player, devoted to his profession, a loyal cat, trustworthy, everything a Boy Scout's supposed to be."

Reggie Jackson once said, "Tom Seaver is so good, blind people come to the park just to hear him pitch."

When Seaver wrote a book listing his choices for the 10 greatest pitchers who ever lived, they were, in descending order: Walter Johnson, Christy Matheson, Koufax, Lefty Grove, Cy Young himself, Bob Feller, Carlton, Bob Gibson, Warren Spahn, and his former Met teammate, Nolan Ryan. The only complaints Seaver got over the book was from people saying he forgot to include himself.

I was once the scorekeeper for my hometown's American Legion baseball team, and our best pitcher was a Met fan who idolized Seaver to the point where he not only wore Number 41, but copied Seaver's drop and drive, right down to the sand stain on his right knee.

In one game, the opposing pitcher also wore 41, and he had nothing that day, and our 41 said, "This guy's making Seaver look like an asshole." He was replaced by a pitcher who wore Number 36, and he was no better. This was before David Cone came to the Yankees, so he wasn't yet identified with that number. I said, "Now, this guy's making Robin Roberts look bad."

Roberts was still alive at the time, but his last season in the major leagues was the year before Seaver arrived, and we were a bit closer to New York than to Philadelphia, and nobody knew who I was talking about. (Roberts now has a statue outside Citizens Bank Park in Philadelphia, so his legacy is more secure than it was then.)

In 1973, Seaver helped the Mets win another Pennant. But Yogi Berra, who became manager upon Hodges' death just before the 1972 season, gambled on closing the Oakland Athletics out in Game 6, by pitching Seaver on 3 days' rest. It didn't work, as Reggie hit a home run, and did the same against Jon Matlack in Game 7, as the A's repeated as World Champions.

Reggie Jackson, who would become the defining Yankee of his generation, and Tom Seaver, the greatest Met of any generation, faced each other 39 times, the first in the 1973 All-Star Game, the last in a Red Sox-Angels game in 1986. Aside from the possibility of Spring Training games (and I don't think the matchup ever happened in Florida in March), they never faced each other with Reggie in Yankee Pinstripes and Tom in Met Blue & Orange.

But Tom also walked him 5 times, including 3 in their final appearance, showing that Tom, then approaching his 42nd birthday, had a lot less left than Reggie, a year and a half younger. Two weeks before that, Reggie had taken Tom deep twice and been hit with a pitch. (That was almost certainly an accident: Seaver was never known to hit someone on purpose, even after that kind of hitting against him.)

Of Reggie's 7 hits against Tom, 2 were doubles and 3 were homers, and he had 6 RBIs. On-base percentage, .333. Slugging percentage, .454. OPS, .787. In other words, Tom pretty much handled Reggie as well as he handled most hitters: Very well. On the other hand, Reggie pretty much did to Tom what he did to most pitchers: When he didn't make contact, it was bad; but when he did make contact, hoo, boy.

Seaver wanted to remain a Met for the rest of his career, but wanted more money and over a longer period of time, guaranteed. This was hardly an outrageous demand,, based on his performance, and the fact that he was still just 32 years old.

Wrong: Grant acted as though he was the true owner of the Mets, and he took this as a grave personal insult. (Well, maybe it was, but he deserved it.)

Aside from possibly Whitey Ford, Seaver was the best pitcher that Young would ever see pitch for a New York team, but he was now tight with Grant. Grant asked him to write a column smearing Seaver. Young didn't need much convincing. He probably traded it for a drink. He was probably happy to do it.

Here is a summary of the most infamous sports column in the history of New York newspapers, from the Daily News of June 15, 1977 -- at the time, June 15 was the trading deadline in MLB:

Young wrote about what "a man" does. A man may disagree with another man, but a man does not bring the other man's family into it. That is a line that a man does not cross. Ever.

You got a problem with someone? Fine. But leave the family out of it. By playing Major League Baseball, Tom Seaver had made himself a public figure. Nancy Seaver was not a public figure until Dick Young made her one, and for what? Selling a few newspapers, and doing his pal M. Donald Grant a big fat favor.

"That Young column was the straw that broke the back," Seaver told the Daily News in 2007, on the 30th Anniversary of the event. "Bringing your family into it, with no truth whatsoever to what he wrote. I could not abide by that. I had to go."

As the Daily News' front page put it, "His wish is M. Don Granted."

In exchange for the legend, 32 years old but still one of the game's top pitchers, the Mets got:

* Steve Henderson, 24, who made his major league debut for the Mets the next day, and became a decent hitter and a good left fielder, finishing 2nd in the NL Rookie of the Year voting, behind Andre Dawson of the Montreal Expos.

* Doug Flynn, 26, stuck behind Joe Morgan in Cincinnati, but then became one of the best-fielding 2nd basemen in baseball in Flushing Meadow, winning a Gold Glove in 1980, although never making an All-Star Team and never becoming much of a hitter.

* Pat Zachry, 25, a pitcher who had finished in a 1st place tie in the vote for the previous year's NL Rookie of the Year, with pitcher Butch Metzger of the San Diego Padres -- but, stricken by injury, would himself be traded to the Mets in 1978, ending his career with them that season. Zachry would be an All-Star in 1978, going 10-6 for a bad Met team.

* And Dan Norman, 22, a right fielder who made his major league debut that September, and never amounted to much; essentially, he was a throw-in, to make it look like the Mets had actually gotten 4 serviceable major leaguers for Seaver.

And yet, by Opening Day 1981, Henderson and Norman would be gone; by Opening Day 1982, so would Flynn; by Opening Day 1983, so would Zachry. By the time Seaver pitched his last major league game, Henderson was the only 1 of the 4 still playing in the majors.

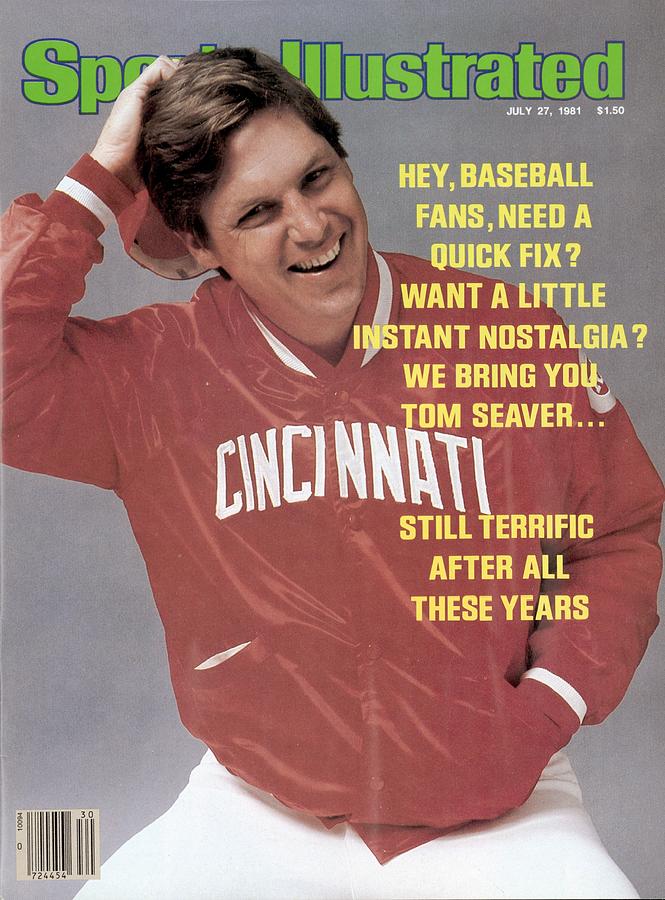

True, the Mets didn't exactly get nothing for Seaver. They got some value for him in 1977. They still didn't get as much value for Seaver as Seaver gave the Reds from June 18, 1977 to August 15, 1982 (a season cut short by injury), including 2 more All-Star seasons in 1978 and 1981, pitching the only no-hitter of his career in 1978, leading the NL in shutouts and getting them to its Championship Series in 1979, leading it in wins and winning percentage in 1981, nearly winning a 4th Cy Young Award that year.

The Padres didn't keep Kingman long, soon trading him to the Angels, who then waived him, and he was picked up for the stretch run by the Yankees, making him the 1st man to play for 4 major league teams in 1 season in the 20th Century, and the 1st man to play for the Mets and the Yankees in the same season. He was not, however, included on the Yankees' ALCS or World Series roster.

Interestingly, when the Mets got Kingman back in 1981, from the Chicago Cubs, where he'd thrived, the player they sent to get him was Steve Henderson.

With Watergate and its "Saturday Night Massacre" -- which happened mere hours after Seaver was the losing pitcher when the Mets lost Game 6 of the 1973 World Series -- still fresh in the memory, and the Yankees having made a trade in 1974 that was known as "the Friday Night Massacre," these 2 Met trades became known as "the Midnight Massacre."

The effect on attendance was staggering. The following Saturday, June 18, was Banner Day, and the Mets drew 52,784, nearly a sellout. On August 21, not just a Sunday but also Seaver's 1st game back at Shea with the Reds, the Mets drew 46,265. Minus those 2 games, their average attendance from June 16 to September 23, 1977 (their last home date of the season) was 13,243 -- only a little more than they were getting without Seaver before the trade, and 10,000 per game less than they got when he pitched.

And, let's be honest about this: Having Seaver, even if the Mets had those other 4 players as well, would have made no difference: The Mets were nowhere near Playoff contention from 1977 to 1982, when he was in Cincinnati, and his pitching wouldn't have won enough games to get them into contention.

There is even a theory that suggests that losing Seaver may have been for the best, since the Mets would have been a little better, and wouldn't have accumulated the draft picks that helped build The Dynasty That Never Was, including the 1986 World Championship. In other words, had Tom Seaver stayed, the Mets would not have won the World Series since 1969 -- not once in my entire lifetime -- and we would now be talking about the Curse of Amos Otis, instead of the Curse of Kevin Mitchell.

The world of baseball had changed, to the point where players now had the freedom to get paid based on performance, and to play where they wanted; and M. Donald Grant was saying, essentially, "No, the world has not changed, not on my watch!"

Throw in the fact that the Yankees were titleholders in the American League, had a renovated Yankee Stadium that was better than Shea, had the defending AL Most Valuable Player in Thurman Munson, had the game's best relief pitcher in Sparky Lyle, and had recently acquired the game's most charismatic slugger in Reggie Jackson, and any pretensions the Mets had to being the most popular, and the most respected, baseball team in New York were gone. Until 1984, anyway.

For Met fans, this was, to borrow Don McLean's phrase about the 1959 plane crash that killed Buddy Holly, "The Day the Music Died." They treated it as if their childhood was over. They reacted to it the way their parents (or big brothers) did when the Dodgers (or Giants) left in 1957. They cried over this as if Seaver had died. As if Seaver had been assassinated by M. Donald Grant, and their youth had died with him.

Babe Ruth left the Yankees in 1935. Joe DiMaggio retired in 1951. Mickey Mantle retired in 1969. Reggie Jackson was not re-signed for 1982. Mariano Rivera retired in 2013, and Derek Jeter retired in 2014. On none of those occasions did Yankee Fans react like a child who had been told his dog was "taken to a farm upstate."

There were 2 times when Yankee Fans did react like that. The 1st was for Lou Gehrig in 1939. Except he actually was going to die. The 2nd was for Thurman Munson in 1979. And he actually did die.

Great players leave. Great players come to take their places. It was time for Met fans to grow up.

*

Lorinda de Roulet finally fired Grant in 1978. By that point, attendance at Shea Stadium was so sparse, it was being called Grant's Tomb: It had gone from a City record 2.7 million fans in the 1970 season to under 800,000 by 1979 -- or, per game, from 33,000 to 9,740. Contrast that with the Yankees: In 1972, they bottomed out at 966,000 (12,000 per game), their lowest since World War II; by 1980, they had risen to 2.6 million (32,000).

Not until 1980 did things begin to turn around at Shea. That was the year when Lorinda sold the team to Fred Wilpon and Nelson Doubleday. They hired Frank Cashen, who helped build the Baltimore Orioles team that dominated the American League from 1966 to 1971, as general manager. His drafts and trades built the Mets into a contender by 1984, and a World Champion in 1986.

Tom Seaver was not killed by M. Donald Grant on June 15, 1977. His life and career continued to flourish. On June 16, 1978, he pitched a no-hitter for the Reds, something he never did with the Mets. The Big Red Machine beat the Cardinals 4-0 at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati.

I was 15 years old, and, with my parents' permission (they, along with my grandmother, would be going with me), I called Ticketmaster the preceding Tuesday, and ordered the tickets, neither knowing nor caring who would be the day's opposing starting pitchers.

The next day, Wednesday, the starters for the Sunday game were announced: Joe Cowley for the Yankees, and Tom Seaver for the White Sox. Interestingly, while Seaver had made the uniform Number 41 iconic in baseball, Cowley was wearing it for the Yankees at the time.

At that point, Cowley had 19 career wins, a total that would eventually rise to 33. Seaver had 299 career wins. In other words, he would be going for his 300th win, and I would be there. Good thing I didn't wait a day to order the tickets: I wouldn't have had a chance otherwise. We sat in box seats in Section 35 in right field. Making it weirder, Cowley was also wearing Number 41 that day.

The ceremony for Rizzuto was great. Several of his Yankee teammates showed up, including Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford. This was the first time I'd ever seen either of them in person. Ex-teammate Yogi Berra, who had managed Seaver with the Mets, was not there, having recently been fired by Clyde King on behalf of George Steinbrenner, and having begun what turned out to be a 14-year boycott of the Yankee organization.

The Yankees manufactured a run in the 3rd inning, and led 1-0 after 5. But in the top of the 6th, in the space of less than 10 minutes, the Yankees went from 1-0 up to 4-1 down. Seaver set the Yankees down in order in both the 6th and the 7th. In the 8th, he began to tire, but worked out of it.

The Yankees did threaten in the bottom of the 9th. Dan Pasqua led off with a single. Seaver reared back, and struck Ron Hassey out. He got Willie Randolph to fly to right. But he walked Mike Pagliarulo.

That brought the tying run to the plate, but it was Bobby Meacham, then batting an inept .232. Manager Billy Martin knew that he needed baserunners, and went for broke, sending the crafty veteran Don Baylor up to pinch-hit.

Baylor was 36. Seaver was 40, had gone the distance, was in his 2nd straight struggling inning, and had to be gassed at this point. But he reared back, reached into his bag of tricks -- one of the greatest arrays of "stuff" any pitcher has ever had -- fired, and his pitch reached the inside corner, a perfect strike.

But Baylor swung, and connected. In almost any other ballpark, this might have been a game-tying home run. But in the old Yankee Stadium, with its left-center "Death Valley," it was just a long fly. Reid Nichols, who had replaced Law in left field for Chicago, caught it. Ballgame over. White Sox win.

All 54,032 in attendance rose as one to applaud Seaver off the field, just as La Russa had intended. Yes, at age 40, Tom Terrific had pitched a complete game, allowing just 1 run, 6 hits, and just 1 walk. He had notched 7 strikeouts. Truly, we had seen a master of his craft at work.

From Section 35 in right field, I had a good view of Seaver and the strike zone. Though I hate to lose, and I hate the Mets, all I could do was stand and tip my cap to Seaver. It was the only time I ever saw him pitch live. The entire broadcast of the game is available on YouTube, if you're so inclined. Here's the last out.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/60074771/tom_seaver_getty2.0.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment