Lou Brock and his wife Jackie were both ordained ministers. Surely, at some point, they must have preached about the Eighth Commandment -- or the Seventh, if you're Catholic: "Thou shalt not steal."

Which would have been a tad ironic in Lou's case. But, also in his case, his thefts were not only legal, but encouraged, and made him a legend. Baseball presents a different kind of immortality than the one Christianity teaches.

Now, Lou is a part of both.

Louis Carl Brock was born on June 18, 1939 in El Dorado, in southern Arkansas. He grew up a few miles over the State Line, in Collinston, Louisiana. Being black in the 1940s and '50s, he loved baseball and became a fan of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who had reintegrated the game with Jackie Robinson.

He didn't start playing baseball in any organized way until his junior year at Union High School in Monroe, Louisiana, but he got a scholarship to play the sport at Southern University in the State capital of Baton Rouge, considered the black counterpart to the then-all-white Louisiana State University (LSU).

In 1959, he led Southern to the NAIA Championship, and was selected for the U.S. team at the 1959 Pan American Games, a Western Hemisphere "mini-Olympics," held that year in Chicago. Playing at the Cubs' Wrigley Field and the White Sox' Comiskey Park, the U.S. team only won the Bronze Medal, with Venezuela taking the Gold.

The 3rd baseman on that team would win an Olympic Gold Medal, but in hockey: He was Jack McCartan, the goaltender on the 1st U.S. team to win Gold at the Winter Olympics, in Squaw Valley, California in 1960.

In spite of being a Dodger fan, the team best able to reach Brock was the St. Louis Cardinals, thanks to their powerful radio network, including stations all through the South and West. Until the Kansas City Athletics in 1955, they were Major League Baseball's westernmost team; and, until the Houston Colt .45's (Astros) in 1962, they, the Cincinnati Reds and the Washington Senators were the southernmost teams.

So when a Cardinal scout recommended him to the club in 1960, Brock went to St. Louis to try out. But the scout in question was in Seattle, where he ended up signing pitcher Ray Washburn, who would also be a notable contributor to the Cardinals' Pennant teams of the 1960s. Brock then went to Wrigley Field to try out for the Chicago Cubs, and was signed as an amateur free agent. In 1961, with the Minnesota-based St. Cloud Rox, he won the Northern League batting championship with a .361 average.

That earned him a major league callup at the end of the season. On September 10, 1961, he made his major league debut at Wrigley. Wearing Number 24, he played center field and led off, against a future Hall-of-Famer, Robin Roberts of the Philadelphia Phillies. He singled off Roberts in his 1st at-bat, but that would be his only hit. In one of the few highlights in a disastrous season for the Phillies, they beat the Cubs 14-6.

In 1962, with future Hall-of-Famer Billy Williams entrenched in left field, Brock became the Cubs' regular center fielder. On June 17, in the 1st game of a doubleheader against the expansion Mets, he became only the 2nd player ever to hit a ball into the faraway center field bleachers at the Polo Grounds. (The Cubs swept the doubleheader, 8-7 and 4-3.)

But this was an anomaly for him: He only hit 9 home runs on the season. That the wind blows out at Wrigley Field is well-known, and this, combined with relatively close power alleys, makes it a good hitter's park. Lesser-known is the fact that the wind blows in half the time, and this, combined with relatively faraway foul poles, makes it a good pitcher's park on those occasions.

Brock was never going to be a Wrigley Field type of player, displaying the kind of slugging ability that led to one-dimensional players like Hack Wilson, Hank Sauer, Bill Nicholson, Jim Hickman and Dave Kingman being said to have "oafish clout."

Only 4 players ever hit a ball into the center field bleachers at the Polo Grounds, and Brock was easily the least likely to have done it. Luke Easter was 1st, in a Negro League game, for the Homestead Grays in 1948. Joe Adcock of the Milwaukee Braves was the 1st major leaguer to do it, against the New York Giants in 1953. The day after Brock's feat, the Braves came in, and Hank Aaron did it. Once in major league competition in the stand's 1st 39 seasons (this was part of a 1923 expansion of the 1911 ballpark), then twice in 2 games. That's how life went for the early Mets.

*

But Brock simply didn't impress Cub management, either at the plate or in the field. And so, needing pitching, on June 15, 1964, just 3 days before his 25th birthday, they traded Brock and pitchers Paul Toth and Jack Spring to the Cardinals, for pitchers Ernie Broglio and Bobby Shantz, and outfielder Doug Clemens.

No one knew it at the time, but Toth had already made his last major league appearance, and Spring would make his last the following season. Clemens was a career backup, and last played in 1968. Shantz was the 1952 American League Most Valuable Player, winning 24 games for the Philadelphia Athletics, and had helped the Yankees win the 1956 and 1958 World Series, but was winding down, and retired after the season.

For the Cubs, the key to the trade was Broglio. At the time of the trade, he was 27 years old, almost 28, and had already won 70 games in the major leagues, against just 55 losses, all for the Cardinals. He led the NL with 21 wins against just 9 losses for a rather ordinary Card team in 1960, finishing 3rd in the voting for the Cy Young Award behind Vernon Law of the World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates and future Hall-of-Famer Warren Spahn of the Milwaukee Braves -- and remember, that was an award for the most valuable pitcher in both leagues at the time. The year before the trade, 1963, he went 18-8 for an improving Cardinal team.

Ernie Broglio

True, he was just 3-5 at the time of the trade in 1964, but trading for him made sense: The Cubs needed to improve their pitching, and Broglio was a proven major league winner. The problem was, he didn't tell anyone at the time, but he was suffering from an injured elbow since the 2nd half of the 1963 season. He had to have his ulnar nerve reset after the 1964 season. If the Cubs had known about his injury, chances are, they wouldn't have traded for him.

This trade has gone down as one of the most lopsided ever. But, as I said, the Cubs didn't know Broglio was injured, and Brock simply wasn't a good fit for the Cubs.

The Cardinals, on the other hand, had Gold Glove winner Curt Flood in center field, and moved Brock to left field, where his defensive improved.

More than that, for most of the last 100 years, the Cardinals have been built around pitching, defense, contact hitting and baserunning. Speed, speed and more speed was a Redbird hallmark at Sportsman's Park and Busch Memorial Stadium, long before Whitey Herzog came along.

True, the Cards have had some big boomers, such as Rogers Hornsby, Joe Medwick, Johnny Mize, Stan Musial, Roger Maris at the end of his career, Jack Clark, Albert Pujols, Matt Holliday and Paul Goldschmidt.

But when you think of offensive players for the St. Louis Cardinals, you think of "Gashouse Gang" players like Pepper Martin, the scrappy, hard-charging "Wild Hoss of the Osage"; and guys who followed in that tradition. Guys like Enos Slaughter and Marty Marion.

At the time Brock arrived, they had Flood, Julian Javier, and the veteran former MVP winner Dick Groat. As Groat faded, Bobby Tolan took his place on the basepaths (if not in his exact position). Later on, there were Herzog-style players such as Ozzie Smith, Willie McGee and Vince Coleman.

An exception to this was their 1997-2001 interlude with Mark McGwire, and they paid for it by being a very mediocre ballclub, although they did reach the NL Championship Series in 2000, though this proves my point because McGwire was hurt a lot that season.

This is what Brock's career statistics looked like on June 15, 1964, at which point he was 3 days away from turning 25, a point at which most guys who end up becoming baseball stars have already begun to show that they will do so:

BA .257

OBP .306

SLG .383

OPS+ 88

Hits 310

2B 52

3B 20

HR 20

RBI 86

Runs 183

SB 50

All-Star appearances 0

Postseason appearances 0

Do those numbers say "Future Hall-of-Famer" to you? Because they sure don't say that to me. But check out his numbers for his entire career:

BA .297

OBP .347

SLG .414

OPS+ 109

Hits 3,023

2B 434

3B 121

HR 149

RBI 814

Runs 1,610

SB 938

All-Star appearances 6

Postseason appearances 3

Would Brock have had career stats like those if he'd stayed with the Cubs? There's no way to know. But then, there was no way to know that an additional 2,700 hits and nearly 900 stolen bases were coming after June 15, 1964.

After batting just .251 with the Cubs through that date, Brock batted .348 the rest of the way for the Cardinals, batting a career-high .315 overall. He finished with 14 home runs 58 RBIs and 43 stolen bases. Led by Brock, pitcher Bob Gibson, and 3rd baseman and Captain Ken Boyer, that season's National League Most Valuable Player, the Cards surged in September, and took advantage of the Phillies' epic 10-game losing streak, and won the Pennant on the last day of the season.

BA .257

OBP .306

SLG .383

OPS+ 88

Hits 310

2B 52

3B 20

HR 20

RBI 86

Runs 183

SB 50

All-Star appearances 0

Postseason appearances 0

Do those numbers say "Future Hall-of-Famer" to you? Because they sure don't say that to me. But check out his numbers for his entire career:

BA .297

OBP .347

SLG .414

OPS+ 109

Hits 3,023

2B 434

3B 121

HR 149

RBI 814

Runs 1,610

SB 938

All-Star appearances 6

Postseason appearances 3

Would Brock have had career stats like those if he'd stayed with the Cubs? There's no way to know. But then, there was no way to know that an additional 2,700 hits and nearly 900 stolen bases were coming after June 15, 1964.

In the World Series against the Yankees, Brock batted .300 with a homer and 5 RBIs. Oddly, he didn't attempt a single steal of any base. The Cardinals won the Series in 7 games, their 1st title in 18 years.

*

In 1965, Brock really took off -- not quite literally, but close, stealing 63 bases. In 1966, as the Cardinals moved from Sportsman's Park on the North Side of St. Louis to the new Busch Memorial Stadium downtown, he stole 74, leading the NL. This began a string of leading the NL in steals in 8 of the next 9 seasons.

He had his best overall season in 1967, batting .299, with career highs in hits with 206, home runs with 21, and RBIs with 76. He stole 52 bases, and led both leagues with 113 runs scored. The Cardinals, having added former Yankee slugger Roger Maris and former San Francisco Giants star Orlando Cepeda, won the Pennant going away. Brock collected 12 hits in the World Series, including a home run, with 3 RBIs, and set a Series record with 7 stolen bases. The Cardinals beat the Boston Red Sox in 7 games.

In 1968, Brock led both leagues with 46 doubles, 14 triples and 62 stolen bases. The Cards ran away with the Pennant again (yet again, figurative, but not quite literal), and faced the Detroit Tigers in the World Series. Brock tied the Series records with 13 hits (which Bobby Richardson of the Yankees had gotten against the Cards in the losing cause of 1964) and 7 steals (which Brock himself had done the year before), and batted .464 with 2 home runs and 5 RBIs.

Robin Yount of the Milwaukee Brewers tied the record of 13 hits in 1982, and Marty Barrett of the Red Sox did it 1986, but, like Richardson and Brock, did so in a losing cause. No one has yet done 13 on the winning side, and no one has yet done 14.

But for all he did in the Series, Brock turned out to be its goat. In Game 5, with the Cardinals leading 3-2 in the 5th inning, and needing only to hold that lead to win the title, he tried to score from 2nd base on a Javier single. He failed to slide, and a great throw from Willie Horton nailed him at the plate. The Tigers won, and sent the Series to a Game 7. In it, Mickey Lolich picked him off 1st base, and he lost his footing in center field at Tiger Stadium, allowing a Jim Northrup drive to drop in for a triple, leading to the Tigers' winning rally.

*

Brock's .391 batting average in World Series play is the highest for anyone with at least 20 games, and his 14 stolen bases is also a Series record -- which is especially amazing when you consider that he attempted none in 1964.

But he would never play in another postseason game. Although he was still one of the top players in the game, age was catching up to the Cardinals, and some bad traded doomed them in the 1970s, as they fell a little short of winning the National League Eastern Division in 1973 and 1974.

But that 1974 season would be Brock's masterpiece. He batted .306, and on September 10, at Busch Stadium, 13 years to the day after his major league debut, he broke Maury Wills' 1962 major league record of 104 stolen bases. He ended up raising the record to 118, and finished 2nd to Steve Garvey of the Pennant-winning Los Angeles Dodgers in the NL MVP balloting.

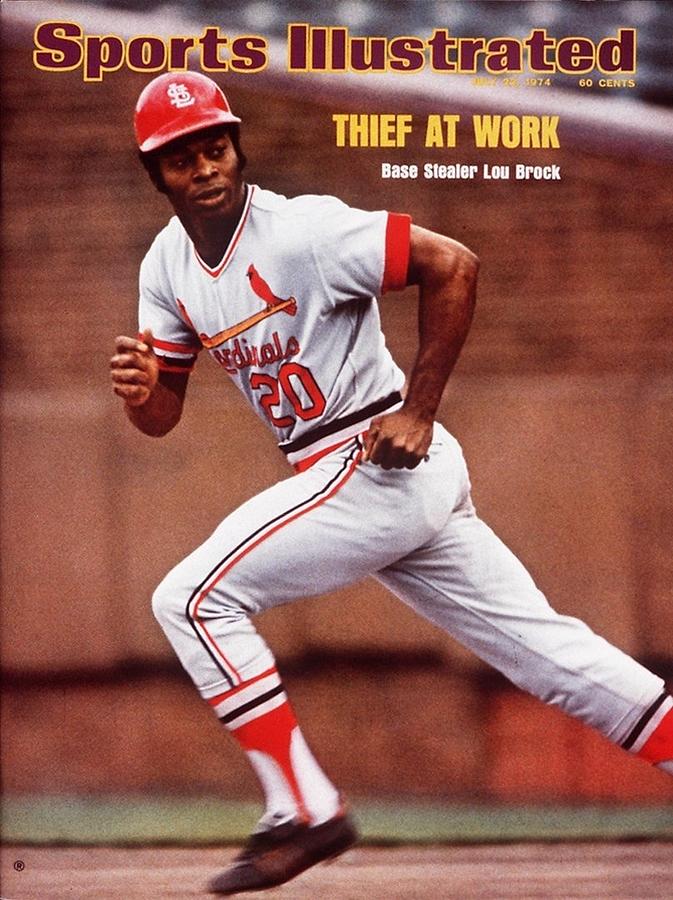

Perhaps "The Dreaded SI Cover Jinx" cost the Cards the NL East title,

as karma for taunting the Cubs on the 10th Anniversary of the trade

but making the cover Brock running at Wrigley Field.

Asked about the art of stealing bases, he said, "The only sure way to stop me is, don't let me reach first base." He also said, "First base is useless, and, most of the time, it is useless to stay there. On the other hand, second base is really the safest place on the field. When I steal second, I practically eliminate the double play. And I can score on any ball hit past the infield."

In words that would have been appreciated by his hero, the oft-distracting Jackie Robinson, "The most important thing about base stealing is not the steal of the base, but distracting the pitcher's concentration. If I can do that, then the hitter will have a better pitch to swing at, and I will get a better chance to steal."

The 1974 season would be the last in which Brock led the NL in steals, although he stole 56 bases in each of the next 2 seasons, and 35 in 1977. On August 29, 1977, against the San Diego Padres, at what was then named San Diego Stadium, he stole the 893rd base of his career, surpassing Ty Cobb, and, as far as MLB officially said, becoming the all-time leader.

Number 893. Ugh, powder blue road uniforms.

For once, the Padres were the better-dressed team.

On August 13, 1979, Brock bedeviled the Cubs one more time. At Busch Stadium, he hit a ball up the middle off Dennis Lamp -- literally: Lamp tried to field it with his bare hand, his pitching hand, and couldn't. Brock reached 1st base, and was credited with a hit. It was the 3,000th hit of his career, making him the 14th member of the 3,000 Hit Club. (Carl Yastrzemski of the Red Sox would achieve the milestone a month later.)

He retired at the end of that season, with a .297 lifetime batting average, 3,023 hits, including 434 doubles, 121 triples, and 149 RBIs. Oddly, he only played in 6 All-Star Games, and never won a Gold Glove. Later, someone determined that the real all-time leader in stolen bases was a star at the end of the 19th Century, Billy Hamilton, with 937. So, no one realized it, but Brock became the all-time leader with the last steal of his career, his 938th.

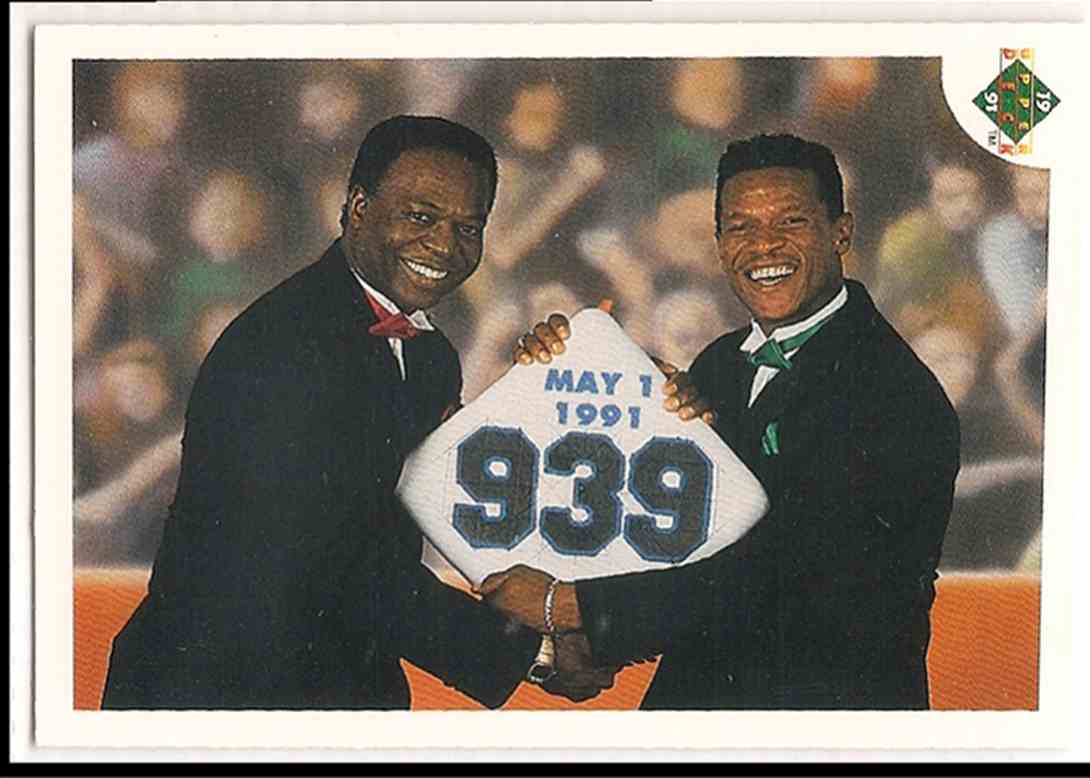

He still holds the NL records for most steals in a season, and in a career. But the major league records were taken from him by Rickey Henderson: 130 in a season, 1982; and a whopping 1,406 in a career.

A commemorative baseball card

celebrating Henderson surpassing Brock

*

Brock was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1985. The Cardinals retired his Number 20, elected him to their team Hall of Fame, and erected a statue of him outside the new Busch Stadium that opened in 2006, adjacent to the site of the old one. He was also elected to the Sports Halls of Fame of Arkansas, Louisiana and Missouri, and to the St. Louis Walk of Fame, which honors local heroes, native and adopted, from all walks of life. In 1999, The Sporting News ranked him 58th on their list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, and he was named as a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.

He tried broadcasting, with ABC on Monday Night Baseball in 1980, and with the Chicago White Sox the next year.

From 1960 to 1974, he was married to Katie Hay. They had a daughter, Wanda, and a son, Lou Brock Jr., who was born shortly before the big trade from Chicago to St. Louis. Lou Jr.'s sport was football, and he played cornerback at the University of Southern California, and in the NFL with the San Diego Chargers in 1987, and with the Detroit Lions and the Seattle Seahawks in 1988. He later worked with phone company Sprint.

From 1976 to 1995, Lou Sr. was married to Virginia Daniels, and they had a son. In 1996, Lou married Jacqueline Layne, a special education teacher. They both became ministers, serving at Abundant Life Fellowship Church in St. Louis.

Lou would be on hand in St. Louis for several special occasions: Mark McGwire's 62nd home run of the 1998 season, the last game at the old Busch Stadium in 2005, the 1st game at the new Busch Stadium the next year, nearly every other Opening Day, the memorial service for Stan Musial in 2013, and the World Series of 1982, 1985, 1987, 2004, 2006, 2011 and 2013.

But he developed diabetes, and in 2015, his left leg was amputated below the knee. In 2017, he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma. His various maladies caught up with him, and he died this afternoon, September 6, 2020, at the age of 81.

The Cardinals' Twitter feed posted, "Our hearts are broken. Lou Brock was an amazing player and outstanding person. He loved the game and all of Cardinal Nation. Rest in peace, Lou."

Ozzie Smith, Cardinals Hall-of-Famer: "Lou Brock the Base Burglar was a class act on and off the field. Made Cardinal baseball what it is. Had the ability to change the momentum of a game with his legs and his bat. May he Rest In Peace. One of the greatest Cardinals of all time."

Albert Pujols, Cardinals superstar now running out the string with the Los Angeles Angels: "Lou Brock was one of the finest men I have ever known. Coming into this league as a 21-year-old kid, Lou Brock was one of the first Hall-of-Fame players I had the privilege to meet. He told me I belonged here in the big-leagues."

Bernie Miklasz, longtime sports columnist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch: "There was a light inside of Lou Brock that brightened every place and space he entered. A light that warmed every person he encountered. Grace. Dignity. Class. Joy. His generosity of spirit touched so many. I’ve never known a finer man. #RIPLou ... Long may you run."

As fate would have it, Lou Brock died on a day when the Chicago Cubs were playing the St. Louis Cardinals at Wrigley Field. And, of course, the Cardinals won, 7-3.

He once said, "They will look at my career as the guy who gave it all, but, at the same time, did it with integrity. That's what we all aim for, the respect of the game, as well as the honesty that's played a part of that game."

He stole more bases than anybody before him, but he was honest. That is the legacy of Lou Brock.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/34243631/3126224.0.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment