In 1999, The Sporting News ranked their 100 Greatest Football Players, and listed Unitas 5th, 2nd among quarterbacks only to the much more recently retired Joe Montana. That same year, ESPN ranked their 50 Greatest Athletes, among all sports, and Unitas came in 32nd. In 2004, The Sporting News listed their 50 Greatest Quarterbacks, and, this time, Unitas was 1st and Montana 2nd. In 2010, the NFL Network listed its 100 Greatest Players, and Unitas was 6th, again trailing only Montana among quarterbacks.

Both the Baltimore Ravens, the team that replaced the Colts after they moved to Indianapolis in 1984, and his alma mater, the University of Louisville, placed statues of him outside their current stadiums. The NCAA's award for the best quarterback of the year is named the Johnny Unitas Golden Arm Award. (Unitas was nicknamed "The Man With the Golden Arm" in the wake of a 1955 Frank Sinatra film of that title.)

It wasn't just his talent. He was a genuinely likable guy. He got the job done, time and time again, without bragging about it. He had several Hall of Fame teammates, and went out of his way to credit them -- and they were happy to return the favor. He embraced his legend status, but used it well. He was good to fans, and obliged requests for advice from younger quarterbacks. And well after the Colts left Baltimore, he didn't, staying loyal to the city that made him famous.

Beyond his talent and his personality, the Colt signal-caller from 1956 to 1972 was praised for his courage, battling through injuries, including having to wear a brace to protect both his injured ribs and his injured back for much of his career.

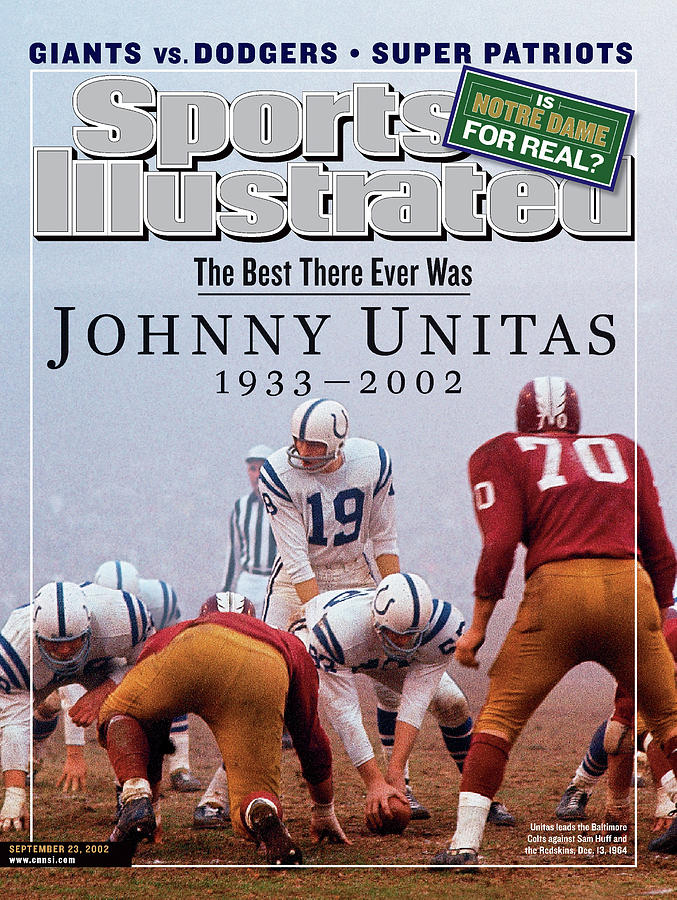

According to the cover, the date is December 13, 1964.

Baltimore Colts 45, Washington Redskins 17,

at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore.

Number 70 for Washington is Hall-of-Famer Sam Huff.

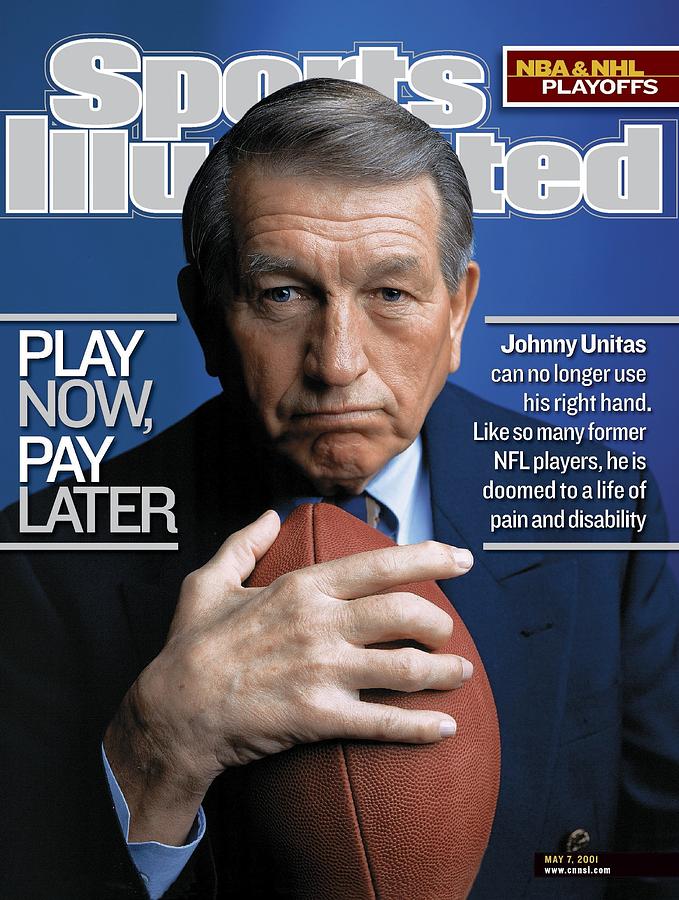

But look at this cover. The date is May 7, 2001, a little over a year before his death. The man often still called the greatest quarterback who ever lived could no longer hold a football properly.

Unitas wasn't the only legend to be seriously injured, long-term, by his play. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Earl Campbell became one of the greatest running backs anybody ever saw. The 1977 Heisman Trophy winner at the University of Texas went on to star for the Houston Oilers.

He was named Most Valuable Player of the National Football League in each of his 1st 3 seasons. Can you imagine a baseball player being so honored? Only twice (and once was dubious, as Ichiro Suzuki was only a "rookie" by the strictest of standards, the other being Fred Lynn) has a baseball player been named Rookie of the Year and MVP in the same season.

He rushed for 6,457 yards in his 1st 4 seasons. In just 4 years, he was halfway to what was then the all-time record, held by Jim Brown. Pardon me for using a technical term, but that's insane.

He wasn't just fast, either: He was tough. Pete Wysocki, a linebacker for the Washington Redskins, said, "Every time you hit him, you lower your own IQ." Cliff Harris, a safety for the Dallas Cowboys, called him "the hardest-hitting running back I ever played against." Lester Hayes, a cornerback for the Oakland Raiders, said, "Earl Campbell was put on this Earth to play football." And his own head coach, Bum Phillips, was asked if Campbell "was in a class by himself." Bum said, "I don't know, but if he ain't, it don't take long to call the roll."

In that 1999 TSN ranking, "The Tyler Rose" (so named for his Texas hometown) was 33rd. In that 2010 NFL Network ranking, he was 55th. Both the University of Texas and the team the Oilers became, the Tennessee Titans, retired his number. Texas not only dedicated a statue of him outside its stadium, but a 2000 poll named him the greatest player in their history, and that's quite a history.

Like Unitas, he has an NCAA award named for him: In 2013, the Earl Campbell Tyler Rose Award was introduced, to be given to the year's best offensive player with Texas ties. (In other words, playing for a Texas school, or coming from Texas but playing elsewhere.) Also like Unitas, he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in his 1st year of eligibility.

But that was in 1991, when he was only 36. He had already been retired for 5 full years, with 9,407 yards. His playing style led to injuries that forced him to retire early. In 2001, only 46, he had arthritis in his hands so bad, he could barely make a fist; and nerve damage in his legs gave him dorsiflexion, a.k.a. "foot drop." In 2009, he not only had been diagnosed with spinal stenosis, effectively putting him in a wheelchair (occasionally, he could use a walker or even just a cane), but went through rehabilitation to break an addiction to the painkilling drug OxyContin. He is still alive, at age 64, but doesn't make many public appearances.

Campbell, honored at a Houston Texans game

It could be worse. Gale Sayers burst onto the scene in 1965, giving the Chicago Bears perhaps the greatest rookie season any NFL player has ever had, even better than Campbell's. In 1 game, he scored a record-tying 6 touchdowns. He scored a record-setting (since broken) 22 touchdowns that season -- and 22 was also his age.

"Give me 18 inches of daylight. That's all I need."

-- Gale Sayers, interviewed for a 1967 NFL Films production

He should have become the greatest Bears running back of them all, ahead of Red Grange, Bronko Nagurski, Willie Galimore, and the yet-to-come Walter Payton, the man who finally broke Jim Brown's career rushing yards record, before being surpassed himself by the current holder, Emmitt Smith.

He didn't, because he wrecked both knees. In 1969, despite the Bears going through a 1-13 season, the worst in their 100-year history, and teammate Brian Piccolo dealing with cancer, and having no cartilage in his knees, Sayers led the NFL in rushing yards. Piccolo died the next year, and Sayers retired after the 1971 season, the physical and psychological toll the game took on him finally being too much.

He ended up playing only 68 games, a little over 4 seasons' worth under today's 16-game schedule. He finished with just 4,956 yards, about half what Campbell would gain. His 5.0 yards per carry still ranks 2nd in NFL history, behind Brown's 5.2.

Despite the brevity of his career, the 1999 TSN poll and the 2010 NFL Network poll both ranked him 22nd. The Bears and the University of Kansas retired his number. He was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame at age 34, the youngest-ever electee to one of the "Big Four" sports halls of fame. (Brown and Sandy Koufax were 36.)

Having more of a post-playing life than most athletes -- or so it appeared -- he made the most of it. He founded a technology services company that took off during the computer revolution of the 1980s, and he used the proceeds to fund charities in the Chicago area and in Kansas. He should have been considered one of the greatest examples of what football can do for a man, and vice versa.

Instead, like Unitas and Campbell, he is one of the saddest examples of what football can do to a man. He took part in one of the "concussion lawsuits" against the NFL in this decade, claiming that he was sometimes sent back into games after suffering a concussion, and that the league -- his team, the officials, the league's administration -- did not do enough to protect him and other players.

He had already been diagnosed with dementia, but that wasn't publicly revealed until 2017. By that point, his memory had been so affected, he could no longer remember how to sign an autograph. He is still alive, but he's not really Gale Sayers anymore. (UPDATE: He died in 2020 -- not from COVID.)

Junior Seau played 20 seasons in the NFL. That's a rarity at any position, but especially for a linebacker. He was named an All-Pro in 12 of those seasons. He was a great player, winning the 1992 Defensive Player of the Year. He was considered a good guy, with his charitable work earning him the 1994 NFL Man of the Year award, which is named for Payton.

The University of Southern California and the San Diego (now Los Angeles) Chargers retired his number. In 2015, he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in his 1st year of eligibility. He was the 1st player of Samoan descent elected.

He did not live to see his election. He shot and killed himself in 2012, only 43 years old. His family, suspecting that he had sustained undiagnosed concussions during his career, donated his brain to the neurological arm of the National Institutes of Health. The following year, the NIH released its findings: Seau's brain showed signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which causes impairment of the brain, including mood swings, memory loss, and reduced motor function. In boxers, this used to be known dementia pugilistica, or being "punch-drunk."

There have been so many others. Mike Webster, Hall of Fame center for the Pittsburgh Steelers, 75th on that 1999 TSN list and 68th on that 2010 NFL Network list, was the 1st former NFL player diagnosed with CTE. "Iron Mike" (he had that nickname before Mike Tyson) had already begun experiencing amnesia as a player in the early 1980s. A doctor later determined that, in 25 years of playing at the high school, college and pro levels, his body, his brain included, had suffered effects comparable to having been in 25,000 car crashes. He died in 2002, only 50.

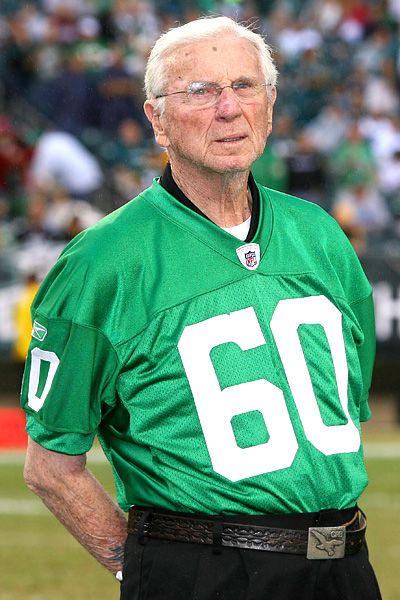

Chuck Bednarik, Hall of Fame center and linebacker for the Philadelphia Eagles in the 1950s, "the last of the 60-minute men," 54th on the 1999 TSN list and 35th on the 2010 NFL Network list, didn't seem to be one of these guys. Into the 21st Century, he was happily sitting for interviews and attending player reunions and memorabilia shows, telling stories about how tough he was, and how tough his time was. As mean as he appeared on the field, he reveled in his role as an NFL elder statesman.

But in 2006, at an Eagles event, he criticized Reggie White, a former Eagles and Green Bay Packers defensive end, who had just been elected to the Hall of Fame. White, still active in 1999, came in 22nd on the TSN list, and 7th on the 2010 NFL Network list. He had died in 2004, only 43, but from an illness that appears not to have had anything to do with playing football.

When Bednarik was ripped in the media for taking shots at a man no longer around to defend himself, he clarified that he made a mistake, that he actually meant to criticize Terrell Owens. Certainly, Owens, then still active, had already been criticized for his attitude and for wasting his great talent. But how do you get T.O. mixed up with Reggie White? How do you get a still-active receiver mixed up with a recently-deceased defensive lineman? Yes, both men had played for the Eagles, and both men were black, but they looked nothing alike.

Bednarik died in 2015. His family had not publicly revealed it before, but they said he had long been dealing with Alzheimer's disease. He was 90, so it's hardly a shock. If he had been anything other than a football player, we'd have considered it just something that happened.

But this was Concrete Charley. The Last of the 60-Minute Men. Until his death, the living embodiment of NFL toughness. A man from an earlier time, when men were men, damn it, not pussyfooting (a term he liked to use) prima donnas with their ridiculous hair (by white and black players alike) and their touchdown celebrations. Of course, we figured it had to have been caused by all his contact.

Sometimes, it gets to guys sooner. In 2005, Chris Henry was a rookie receiver with the Cincinnati Bengals, and was already getting into legal trouble. It got worse, including domestic violence against the mother of his 3 children. In 2009, he was killed in a truck accident. The following year, it was revealed that his brain had signs of CTE. He was only 26.

And then there was Aaron Hernandez. At the conclusion of the 2012 season, the tight end was an NCAA Champion at the University of Florida, a 3-year veteran for the New England Patriots, and had already been to a Super Bowl (one of the ones the Pats lost to the Giants). He seemed to have a good career ahead of him. If all had gone well, he would now be approaching his 30th birthday and have 3 Super Bowl rings in 5 appearances, and be on his way to Canton.

But after that 2012 season, he never played another down. And it wasn't because of any injury -- at least, not that anyone could see. In 2013, he was arrested for murder. He was linked to other murders. He was convicted in 2015. In 2017, he hanged himself in his prison cell. He was 27.

Later that year, the Boston University CTE Center released a statement saying that his brain injuries were consistent with Stage 3 CTE -- out of 4 stages -- calling it "the most severe case of CTE medically seen in a person at his age." It certainly would explain the erratic behavior that people who knew him saw, even if the general public wasn't aware of it before his arrest.

These are the highest-profile cases that we know about. There are many others that we don't know about -- or don't know about yet, because their effects on the players currently active are only beginning.

Tom Brady, Hernandez's former quarterback, just turned 42. He wants to play this season. He wants to play next season. He has 6 rings, lots of money, and enough people willing to overlook his, and his team's, cheating that he's an easy first-year inductee into the Hall of Fame. Why go on, and risk permanent injury?

Some guys are smarter than others. Look at the quarterbacks for the Dallas Cowboys. Don Meredith led the Cowboys into the 1966 and 1967 NFL Championship Games. Had they beaten the Green Bay Packers in either, they would have gone to Super Bowl I and/or II. But he retired at age 30. He went into broadcasting, becoming part of the legendary ABC Monday Night Football broadcast team with Howard Cosell and Frank Gifford.

Despite an obvious Southern drawl (Dallas was his hometown), everybody could tell that Dandy Don was smart, and he never showed any sign of mental decline. While his death, in 2010 at 72, was from a brain hemorrhage, no evidence of CTE was found.

Roger Staubach got the Cowboys into 5 Super Bowls, winning 2, but retired after the 1979 season, after suffering 2 concussions that season. "Captain Comeback" was 37, and still seemed to be at the top of his game. But it must have been the right thing to do, as he is now 77, and shows no sign of brain trauma. (Although his U.S. Navy service, following his Naval Academy graduation, did cost him 4 pro seasons, which may have helped his health, even as it hurt his career statistics.)

Troy Aikman quarterbacked the Cowboys to 3 Super Bowl wins in the 1990s, but he retired after the 2000 season, only 34, concerned over concussions and a back injury. He's now 52, and one of the best TV football analysts, and no one questions his brain.

And, following the examples of Meredith and Aikman, Tony Romo retired after 14 seasons as Cowboy quarterback, and went into broadcasting, and is well-regarded at it. He's 39, so it's hard to guess what the long-term effects of his playing will be, but he seems fine now, and not all ex-NFL players seem fine at 39.

Some guys are smarter than others, and some are just luckier. Jack Kemp may have been both: He turned a nearly Hall of Fame career as quarterback of the 1960s Buffalo Bills, retiring at age 34, into 9 terms in Congress, 1 as U.S. Secretary of Housing & Urban Development, and the 1996 Republican nomination for Vice President.

He liked to tell people, "I sustained 11 concussions during my playing career. Nothing left to do but to go into politics!" It always got a big laugh, because people like to think of the politicians they don't like as being dumb or brain-damaged. When Kemp died in 2009, at 74, it was from cancer, rather than anything football-related.

*

Entering this, its 100th season, the National Football League has more problems than just what the regular (I don't want to say "normal") process of the game does to its players' bodies and brains. Even those players who sustain minor injuries can get cut, discarded like an apple core. Contracts? Just pieces of paper to NFL team owners, all of whom are rich enough to hire the best lawyers in America -- and a few owners have been lawyers.

Fans get screwed over, too. Owners tell cities, "Give me a new stadium, with all the modern amenities, paid for with taxpayer dollars, or I will move the team to a city that will give me one." This sometimes happens only 20 or 30 years after the team -- sometimes, under the same owner -- got one with what was then considered "all the modern amenities," paid for with taxpayer dollars, and sometimes not fully paid off. And if a city calls the owner's bluff, and says, "Screw you, we ain't payin'," they soon find out that the owner wasn't bluffing:

* Al Davis, owner of the Oakland Raiders, didn't like his lease at the Oakland Coliseum. He wanted a new stadium. He didn't get it. So in 1982, he moved his team to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum -- a considerably older stadium. The advantage was that it was a much bigger stadium, but even a good Raider team couldn't sell 93,000 tickets. He got tired of the lack of luxury suites, so he made a deal with Oakland to build a new section of their Coliseum, with luxury suites, and moved back in 1995. But after his death, his son, Mark Davis, got sick of the Oakland Coliseum's age and inadequacy, and is now in the process of moving the Raiders to Las Vegas. Not too many teams managed to screw 2 different cities over, but the Raiders are now unique in having screwed the same city over twice.

* The Minnesota Vikings played 21 years at Metropolitan Stadium, 1961 to 1981, before moving into the Metrodome. By 2010, not yet reaching its 30th Anniversary, baseball's Twins and the football program at the University of Minnesota had already left it, and the stadium had proved inadequate. After threatening to move to Los Angeles and San Antonio, Vikings owner Zygi Wilf cut a deal with the State of Minnesota. After groundsharing at UM's open-air, too-small 51,000-seat stadium for 2 seasons, they moved into the domed, 66,000-seat U.S. Bank Stadium, on the site of the Metrodome, in 2016.

* Bob Irsay, owner of the Baltimore Colts, threatened to move if he didn't get a new stadium. The City of Baltimore couldn't afford it. The State of Maryland wanted certain concessions in exchange, and didn't get them. The Colts moved to Indianapolis, which had a new stadium, in 1984.

* And yet, that new stadium, the Hoosier Dome, only lasted 25 seasons, before Lucas Oil Stadium opened. The City of Indianapolis knew that, being his father's son, team owner Jim Irsay was probably not bluffing, and so they caved in.

* The Atlanta Falcons have now pulled this stunt twice. They played their 1st 26 seasons, 1966 to 1991, at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, then left it for the Georgia Dome, and only played 25 seasons there before moving into a new dome, Mercedes-Benz Stadium, in 2017.

* Art Modell, owner of the Cleveland Browns, threatened to move if he didn't get a new stadium. The City, County and State governments didn't take the threat seriously, and they moved after the 1995 season, becoming the Baltimore Ravens. Cleveland got a new stadium and a new Browns franchise, both debuting in 1999.

* Bud Adams, owner of the Houston Oilers, threatened to move if he didn't get a new stadium. He almost had an agreement to move to Jacksonville in 1988, but he got an agreement for improvements to the Astrodome, and called it off. He later decided that what he'd gotten wasn't enough, and, after the 1996 season, he moved the team, and it became the Tennessee Titans. Jacksonville got the expansion Jaguars in 1995, and Adams' team and the city he once used as leverage are now divisional rivals.

* The Tampa Bay Buccaneers played 22 seasons in Tampa Stadium, 1976 to 1997, before moving into Raymond James Stadium, which has now lasted that long.

* The Cincinnati Bengals played 30 seasons in Riverfront Stadium, 1970 to 1999, before moving into Paul Brown Stadium. (UPDATE: Now named Paycor Stadium. Team owner Mike Brown took his own father's name, the name of the team's founder, off the stadium.)

The University of Southern California and the San Diego (now Los Angeles) Chargers retired his number. In 2015, he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in his 1st year of eligibility. He was the 1st player of Samoan descent elected.

He did not live to see his election. He shot and killed himself in 2012, only 43 years old. His family, suspecting that he had sustained undiagnosed concussions during his career, donated his brain to the neurological arm of the National Institutes of Health. The following year, the NIH released its findings: Seau's brain showed signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which causes impairment of the brain, including mood swings, memory loss, and reduced motor function. In boxers, this used to be known dementia pugilistica, or being "punch-drunk."

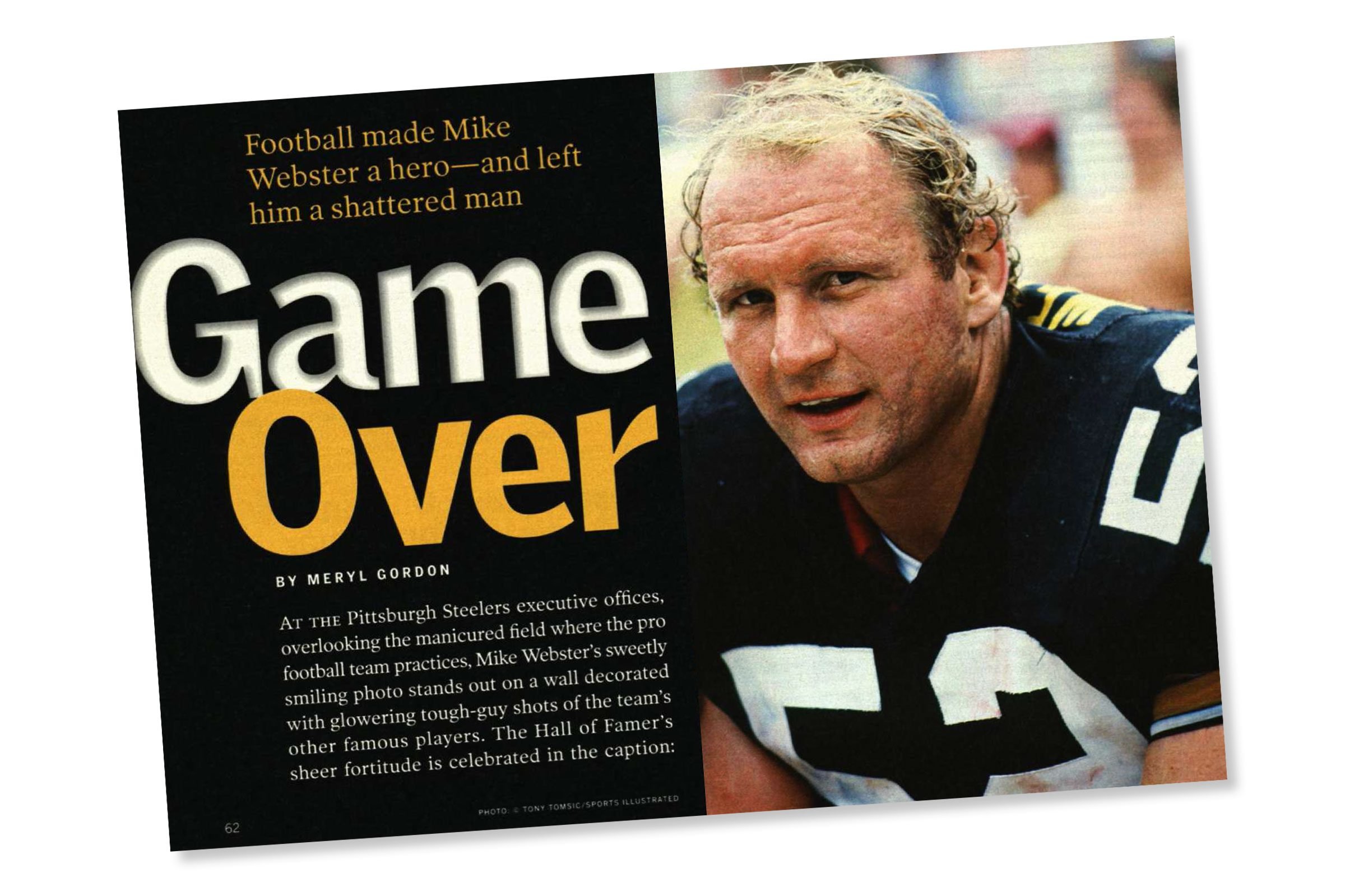

There have been so many others. Mike Webster, Hall of Fame center for the Pittsburgh Steelers, 75th on that 1999 TSN list and 68th on that 2010 NFL Network list, was the 1st former NFL player diagnosed with CTE. "Iron Mike" (he had that nickname before Mike Tyson) had already begun experiencing amnesia as a player in the early 1980s. A doctor later determined that, in 25 years of playing at the high school, college and pro levels, his body, his brain included, had suffered effects comparable to having been in 25,000 car crashes. He died in 2002, only 50.

A 2003 Reader's Digest article about the late Mike Webster

Chuck Bednarik, Hall of Fame center and linebacker for the Philadelphia Eagles in the 1950s, "the last of the 60-minute men," 54th on the 1999 TSN list and 35th on the 2010 NFL Network list, didn't seem to be one of these guys. Into the 21st Century, he was happily sitting for interviews and attending player reunions and memorabilia shows, telling stories about how tough he was, and how tough his time was. As mean as he appeared on the field, he reveled in his role as an NFL elder statesman.

He was called "Concrete Charley," but that was because

of his off-season job, working for a concrete distributor, not for his toughness.

But in 2006, at an Eagles event, he criticized Reggie White, a former Eagles and Green Bay Packers defensive end, who had just been elected to the Hall of Fame. White, still active in 1999, came in 22nd on the TSN list, and 7th on the 2010 NFL Network list. He had died in 2004, only 43, but from an illness that appears not to have had anything to do with playing football.

When Bednarik was ripped in the media for taking shots at a man no longer around to defend himself, he clarified that he made a mistake, that he actually meant to criticize Terrell Owens. Certainly, Owens, then still active, had already been criticized for his attitude and for wasting his great talent. But how do you get T.O. mixed up with Reggie White? How do you get a still-active receiver mixed up with a recently-deceased defensive lineman? Yes, both men had played for the Eagles, and both men were black, but they looked nothing alike.

Bednarik died in 2015. His family had not publicly revealed it before, but they said he had long been dealing with Alzheimer's disease. He was 90, so it's hardly a shock. If he had been anything other than a football player, we'd have considered it just something that happened.

But this was Concrete Charley. The Last of the 60-Minute Men. Until his death, the living embodiment of NFL toughness. A man from an earlier time, when men were men, damn it, not pussyfooting (a term he liked to use) prima donnas with their ridiculous hair (by white and black players alike) and their touchdown celebrations. Of course, we figured it had to have been caused by all his contact.

Sometimes, it gets to guys sooner. In 2005, Chris Henry was a rookie receiver with the Cincinnati Bengals, and was already getting into legal trouble. It got worse, including domestic violence against the mother of his 3 children. In 2009, he was killed in a truck accident. The following year, it was revealed that his brain had signs of CTE. He was only 26.

And then there was Aaron Hernandez. At the conclusion of the 2012 season, the tight end was an NCAA Champion at the University of Florida, a 3-year veteran for the New England Patriots, and had already been to a Super Bowl (one of the ones the Pats lost to the Giants). He seemed to have a good career ahead of him. If all had gone well, he would now be approaching his 30th birthday and have 3 Super Bowl rings in 5 appearances, and be on his way to Canton.

But after that 2012 season, he never played another down. And it wasn't because of any injury -- at least, not that anyone could see. In 2013, he was arrested for murder. He was linked to other murders. He was convicted in 2015. In 2017, he hanged himself in his prison cell. He was 27.

Later that year, the Boston University CTE Center released a statement saying that his brain injuries were consistent with Stage 3 CTE -- out of 4 stages -- calling it "the most severe case of CTE medically seen in a person at his age." It certainly would explain the erratic behavior that people who knew him saw, even if the general public wasn't aware of it before his arrest.

These are the highest-profile cases that we know about. There are many others that we don't know about -- or don't know about yet, because their effects on the players currently active are only beginning.

Tom Brady, Hernandez's former quarterback, just turned 42. He wants to play this season. He wants to play next season. He has 6 rings, lots of money, and enough people willing to overlook his, and his team's, cheating that he's an easy first-year inductee into the Hall of Fame. Why go on, and risk permanent injury?

Some guys are smarter than others. Look at the quarterbacks for the Dallas Cowboys. Don Meredith led the Cowboys into the 1966 and 1967 NFL Championship Games. Had they beaten the Green Bay Packers in either, they would have gone to Super Bowl I and/or II. But he retired at age 30. He went into broadcasting, becoming part of the legendary ABC Monday Night Football broadcast team with Howard Cosell and Frank Gifford.

Despite an obvious Southern drawl (Dallas was his hometown), everybody could tell that Dandy Don was smart, and he never showed any sign of mental decline. While his death, in 2010 at 72, was from a brain hemorrhage, no evidence of CTE was found.

Roger Staubach got the Cowboys into 5 Super Bowls, winning 2, but retired after the 1979 season, after suffering 2 concussions that season. "Captain Comeback" was 37, and still seemed to be at the top of his game. But it must have been the right thing to do, as he is now 77, and shows no sign of brain trauma. (Although his U.S. Navy service, following his Naval Academy graduation, did cost him 4 pro seasons, which may have helped his health, even as it hurt his career statistics.)

Troy Aikman quarterbacked the Cowboys to 3 Super Bowl wins in the 1990s, but he retired after the 2000 season, only 34, concerned over concussions and a back injury. He's now 52, and one of the best TV football analysts, and no one questions his brain.

And, following the examples of Meredith and Aikman, Tony Romo retired after 14 seasons as Cowboy quarterback, and went into broadcasting, and is well-regarded at it. He's 39, so it's hard to guess what the long-term effects of his playing will be, but he seems fine now, and not all ex-NFL players seem fine at 39.

Some guys are smarter than others, and some are just luckier. Jack Kemp may have been both: He turned a nearly Hall of Fame career as quarterback of the 1960s Buffalo Bills, retiring at age 34, into 9 terms in Congress, 1 as U.S. Secretary of Housing & Urban Development, and the 1996 Republican nomination for Vice President.

He liked to tell people, "I sustained 11 concussions during my playing career. Nothing left to do but to go into politics!" It always got a big laugh, because people like to think of the politicians they don't like as being dumb or brain-damaged. When Kemp died in 2009, at 74, it was from cancer, rather than anything football-related.

*

Entering this, its 100th season, the National Football League has more problems than just what the regular (I don't want to say "normal") process of the game does to its players' bodies and brains. Even those players who sustain minor injuries can get cut, discarded like an apple core. Contracts? Just pieces of paper to NFL team owners, all of whom are rich enough to hire the best lawyers in America -- and a few owners have been lawyers.

Fans get screwed over, too. Owners tell cities, "Give me a new stadium, with all the modern amenities, paid for with taxpayer dollars, or I will move the team to a city that will give me one." This sometimes happens only 20 or 30 years after the team -- sometimes, under the same owner -- got one with what was then considered "all the modern amenities," paid for with taxpayer dollars, and sometimes not fully paid off. And if a city calls the owner's bluff, and says, "Screw you, we ain't payin'," they soon find out that the owner wasn't bluffing:

* Al Davis, owner of the Oakland Raiders, didn't like his lease at the Oakland Coliseum. He wanted a new stadium. He didn't get it. So in 1982, he moved his team to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum -- a considerably older stadium. The advantage was that it was a much bigger stadium, but even a good Raider team couldn't sell 93,000 tickets. He got tired of the lack of luxury suites, so he made a deal with Oakland to build a new section of their Coliseum, with luxury suites, and moved back in 1995. But after his death, his son, Mark Davis, got sick of the Oakland Coliseum's age and inadequacy, and is now in the process of moving the Raiders to Las Vegas. Not too many teams managed to screw 2 different cities over, but the Raiders are now unique in having screwed the same city over twice.

* The Minnesota Vikings played 21 years at Metropolitan Stadium, 1961 to 1981, before moving into the Metrodome. By 2010, not yet reaching its 30th Anniversary, baseball's Twins and the football program at the University of Minnesota had already left it, and the stadium had proved inadequate. After threatening to move to Los Angeles and San Antonio, Vikings owner Zygi Wilf cut a deal with the State of Minnesota. After groundsharing at UM's open-air, too-small 51,000-seat stadium for 2 seasons, they moved into the domed, 66,000-seat U.S. Bank Stadium, on the site of the Metrodome, in 2016.

* Bob Irsay, owner of the Baltimore Colts, threatened to move if he didn't get a new stadium. The City of Baltimore couldn't afford it. The State of Maryland wanted certain concessions in exchange, and didn't get them. The Colts moved to Indianapolis, which had a new stadium, in 1984.

* And yet, that new stadium, the Hoosier Dome, only lasted 25 seasons, before Lucas Oil Stadium opened. The City of Indianapolis knew that, being his father's son, team owner Jim Irsay was probably not bluffing, and so they caved in.

* The Atlanta Falcons have now pulled this stunt twice. They played their 1st 26 seasons, 1966 to 1991, at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, then left it for the Georgia Dome, and only played 25 seasons there before moving into a new dome, Mercedes-Benz Stadium, in 2017.

* Art Modell, owner of the Cleveland Browns, threatened to move if he didn't get a new stadium. The City, County and State governments didn't take the threat seriously, and they moved after the 1995 season, becoming the Baltimore Ravens. Cleveland got a new stadium and a new Browns franchise, both debuting in 1999.

* Bud Adams, owner of the Houston Oilers, threatened to move if he didn't get a new stadium. He almost had an agreement to move to Jacksonville in 1988, but he got an agreement for improvements to the Astrodome, and called it off. He later decided that what he'd gotten wasn't enough, and, after the 1996 season, he moved the team, and it became the Tennessee Titans. Jacksonville got the expansion Jaguars in 1995, and Adams' team and the city he once used as leverage are now divisional rivals.

* The Tampa Bay Buccaneers played 22 seasons in Tampa Stadium, 1976 to 1997, before moving into Raymond James Stadium, which has now lasted that long.

* The Cincinnati Bengals played 30 seasons in Riverfront Stadium, 1970 to 1999, before moving into Paul Brown Stadium. (UPDATE: Now named Paycor Stadium. Team owner Mike Brown took his own father's name, the name of the team's founder, off the stadium.)

* The Kingdome lasted 25 seasons, 1976 to 2000, before the Seattle Seahawks left it, temporarily groundsharing with the University of Washington, before a new stadium, now named CenturyLink Field, opened on the same site. (UPDATE: Now named Lumen Field.)

* The Pittsburgh Steelers' Three Rivers Stadium lasted 31 seasons, 1970 to 2000, before being replaced by Heinz Field. (UPDATE: Now named Acrisure Field.)

* The Pittsburgh Steelers' Three Rivers Stadium lasted 31 seasons, 1970 to 2000, before being replaced by Heinz Field. (UPDATE: Now named Acrisure Field.)

* The New England Patriots' Foxboro Stadium lasted 31 seasons, 1971 to 2001, before being replaced by Gillette Stadium, after threats by one owner, James Orthwein, to move the team to St. Louis or Baltimore; and by the next owner, current owner Bob Kraft, to move them to Hartford. The State of Connecticut thought they had a deal with Kraft, until the Commonwealth of Massachusetts gave him a better deal.

* The Detroit Lions' Silverdome lasted 27 seasons, 1975 to 2001, before being replaced by Ford Field.

* The Philadelphia Eagles' Veterans Stadium lasted 32 seasons, 1971 to 2002 (plus 1 more for the Phillies), before being replaced by Lincoln Financial Field.

* Dean Spanos, operating owner of the San Diego Chargers, demanded a new stadium to replace the facility best remembered as Jack Murphy Stadium (now named SDCCU Stadium). The city, one of the most conservative in America, is famously taxophobic, and refused to fund it. Spanos moved the team to Los Angeles for the 2017 season. (UPDATE: The old stadium has been torn down. On the site, the smaller Snapdragon Stadium was built, and is home to San Diego State and MLS' San Diego FC.)

* And, here in the New York Tri-State Area, the New York Giants played their 1st 31 seasons, 1925 to 1955, at the Polo Grounds. Not happy with the stadium or the neighborhood, both crumbling, they moved across the Harlem River to Yankee Stadium. But, knowing that they would be kicked out due to its renovation in 1973, they played "home games" at the Yale Bowl in Connecticut and then at Shea Stadium until Giants Stadium could open in 1976.

* The New York Jets played their 1st 4 seasons, 1960 to 1963, at the Polo Grounds, before moving into Shea Stadium. But they only played 20 seasons there, realizing that "The Flushing Toilet" was no good. So they spent 26 years groundsharing with the Giants at the Meadowlands. But the stadium's owners, the New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority, always gave the Giants first say over everything. Plus, playing home games in a stadium with another team's name on it was demeaning.

* So the Jets threatened to move. They wanted in on Mayor Michael Bloomberg's idea to build an 85,000-seat retractable-roof stadium over the West Side Rail Yards, which would be home to the Yankees, the Jets, other sporting events such as the Super Bowl and the Final Four, concerts and conventions starting in 2008, and also serve as the main stadium for the 2012 Olympics. The deal never happened: The Yankees made a deal with the City for a new Yankee Stadium, the Olympics were awarded to London instead, and the Jets and the other tenants simply wouldn't generate enough revenue to justify the stadium's massive cost, so the City Council said, "Fugeddabouddit."

* So the Jets made the best deal they could, working with the Giants to build a new stadium next-door to Giants Stadium. What's now MetLife Stadium opened in 2010, and each team is half-owner, and they work together to run it and get favorable playing dates. But it meant that Giants Stadium lasted only 34 Giants seasons, albeit with 3 of them ending with the Giants winning the Super Bowl, and just 26 Jets seasons.

(Two ironies about this: There is, sort of, another New York sports team's name on the Jets' home stadium: "MetLife"; and the Yankees did end up playing 2 games in the stadium that was built for the 2012 Olympics, against the Boston Red Sox this past June, in the "MLB London Series.")

*

It's not just the injuries. It's not just ripping the fans off with taxpayer-funded stadiums that these billionaires can afford to build themselves, and never miss the money. Ticket prices are exorbitant. So are parking prices. So are concession prices. God forbid your kid wants a jersey or another thingamabob with the team's logo on it.

Someone once pointed out that, with the TV revenue involved, all 16 NFL teams playing home games in a given weekend could keep the fans out, have official attendances of zero, and still make a profit for the week. Because the fans would still watch on television. (UPDATE: The COVID-forced "behind closed doors" games of 2020 proved this true.)

* The Detroit Lions' Silverdome lasted 27 seasons, 1975 to 2001, before being replaced by Ford Field.

* The Philadelphia Eagles' Veterans Stadium lasted 32 seasons, 1971 to 2002 (plus 1 more for the Phillies), before being replaced by Lincoln Financial Field.

* Dean Spanos, operating owner of the San Diego Chargers, demanded a new stadium to replace the facility best remembered as Jack Murphy Stadium (now named SDCCU Stadium). The city, one of the most conservative in America, is famously taxophobic, and refused to fund it. Spanos moved the team to Los Angeles for the 2017 season. (UPDATE: The old stadium has been torn down. On the site, the smaller Snapdragon Stadium was built, and is home to San Diego State and MLS' San Diego FC.)

* And, here in the New York Tri-State Area, the New York Giants played their 1st 31 seasons, 1925 to 1955, at the Polo Grounds. Not happy with the stadium or the neighborhood, both crumbling, they moved across the Harlem River to Yankee Stadium. But, knowing that they would be kicked out due to its renovation in 1973, they played "home games" at the Yale Bowl in Connecticut and then at Shea Stadium until Giants Stadium could open in 1976.

* The New York Jets played their 1st 4 seasons, 1960 to 1963, at the Polo Grounds, before moving into Shea Stadium. But they only played 20 seasons there, realizing that "The Flushing Toilet" was no good. So they spent 26 years groundsharing with the Giants at the Meadowlands. But the stadium's owners, the New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority, always gave the Giants first say over everything. Plus, playing home games in a stadium with another team's name on it was demeaning.

* So the Jets threatened to move. They wanted in on Mayor Michael Bloomberg's idea to build an 85,000-seat retractable-roof stadium over the West Side Rail Yards, which would be home to the Yankees, the Jets, other sporting events such as the Super Bowl and the Final Four, concerts and conventions starting in 2008, and also serve as the main stadium for the 2012 Olympics. The deal never happened: The Yankees made a deal with the City for a new Yankee Stadium, the Olympics were awarded to London instead, and the Jets and the other tenants simply wouldn't generate enough revenue to justify the stadium's massive cost, so the City Council said, "Fugeddabouddit."

* So the Jets made the best deal they could, working with the Giants to build a new stadium next-door to Giants Stadium. What's now MetLife Stadium opened in 2010, and each team is half-owner, and they work together to run it and get favorable playing dates. But it meant that Giants Stadium lasted only 34 Giants seasons, albeit with 3 of them ending with the Giants winning the Super Bowl, and just 26 Jets seasons.

(Two ironies about this: There is, sort of, another New York sports team's name on the Jets' home stadium: "MetLife"; and the Yankees did end up playing 2 games in the stadium that was built for the 2012 Olympics, against the Boston Red Sox this past June, in the "MLB London Series.")

*

It's not just the injuries. It's not just ripping the fans off with taxpayer-funded stadiums that these billionaires can afford to build themselves, and never miss the money. Ticket prices are exorbitant. So are parking prices. So are concession prices. God forbid your kid wants a jersey or another thingamabob with the team's logo on it.

Someone once pointed out that, with the TV revenue involved, all 16 NFL teams playing home games in a given weekend could keep the fans out, have official attendances of zero, and still make a profit for the week. Because the fans would still watch on television. (UPDATE: The COVID-forced "behind closed doors" games of 2020 proved this true.)

And then there's the perception that the games are rigged. More than any other North American sports league, the NFL has its officials called into question. It used to be the Cowboys that seemed to be the beneficiaries of cheating. Now, it's the Patriots. And when Commissioner Roger Goodell tried to punish Tom Brady and the team in "Deflategate," he was taken to court and overruled. (Well, sort of: Brady's suspension was reduced.)

And, last season, both Conference Championship Games were ruined by the officials. It's bad enough that the Patriots unfairly got calls that allowed them to beat the Kansas City Chiefs, but the Los Angeles Rams got a call that, had it been made correctly, might have led to the New Orleans Saints winning. Result? The lowest-scoring Super Bowl ever, 13-3. Of course, the Patriots won.

NFL fans can't trust the team owners, or the officials, or the League office. And the players are getting killed. Literally. Not immediately: While there have been 5 deaths as a result of on-field play in the NFL's 100-year history (counting the AFL), there hasn't been one since Chuck Hughes of the Detroit Lions in 1971. But retired players are dying, and some not dying yet but suffering terribly, from the effects of their playing.

If team owners are so concerned over money, and protecting their assets, and treating the players as property (an idea that should have been shattered when baseball's reserve clause was struck down in 1975 -- 44 years ago), why don't they do more to protect those assets?

Which brings me back to the quarterback of the Colts. Not Johnny Unitas, their all-time greatest legend. Yes, kids, even over Peyton Manning. I mean the man who, until yesterday, was the current Colts quarterback, a man with the now-ironic name of Andrew Luck.

Coming out of Stanford University, Luck was the 1st pick of the 2012 NFL Draft. The Colts had that pick in that draft because Manning had sustained a neck injury and missed the entire 2011 season, resulting in the Colts going a League-worst 2-14. The Colts decided that, with Manning being 36, they'd be better off letting him go as a free agent, even though they would get nothing for him as they would in a trade, and drafting his replacement now.

It seemed to work well for both teams. Manning was sent to the Denver Broncos, whom he led to 2 Super Bowls, winning 1, before retiring. Meanwhile, Luck quarterbacked the Colts for 7 seasons, making the Playoffs 4 times, winning 2 AFC South Division titles, and making the 2014 AFC Championship Game -- the Deflategate Game. Despite injuries that plagued him in 2017 (he missed the entire season, and the team went 4-12) and 2018 (his delayed debut got them to 10-6 and a Playoff win away to Houston), he looked like he was headed for the Hall of Fame.

Yesterday, Luck held a press conference, and announced his retirement. He said, "I've been stuck in this process. I haven't been able to live the life I want to live. It's taken the joy out of this game. The only way forward for me is to remove myself from football. This is not an easy decision. It's the hardest decision of my life. But it is the right decision for me."

Andrew Luck is 29 years old. He could have become young Johnny Unitas. But he didn't want to become old Johnny Unitas.

*

This is what the National Football League does.

I don't blame the League for wanting to celebrate the hell out of its 100th Season. (It was founded on September 17, 1920, so this is the 100th Season, not the 100th Anniversary.) There is much to celebrate. Much good has been done by the teams and their players. Much joy has been brought to places where the game has been played.

Places like Los Angeles, Denver, San Diego, Tampa, Jacksonville and Phoenix, not previously thought of as "major league" or "big time," got that way through the NFL (or the AFL, which is now considered part of the NFL's history). Other places, such as Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Chicago, have had the successes of their football teams give them an emotional lift at times when, due to economic strife or municipal disharmony (or, in the case of Dallas, the stigma of having a President assassinated there), they really needed it. Buffalo and Los Angeles, which wouldn't seem to have much else in common, qualify on both counts.

But we now know things about football that we didn't know before. And then there are the things that we did know, but didn't want to admit. Football changes people. Not just those contractually involved. Fans change.

I attended 18 Phillies home games at Veterans Stadium. Aside from the stadium's bowl sometimes trapping the heat, the team often being bad, and that artificial turf being hideous, my experiences there were good ones. Only once did I ever have a problem with the home fans, and it was a minor, tolerable thing.

I attended 1 Eagles home game there. It was, if you'll pardon the pun, a whole different ballgame. Eagle fans have a reputation for being among the roughest in the League. It is deserved.

Compare Oakland fans for an A's game, where they're passionate, but mostly sane; and for a Raiders game, where they're animals.

Even in the college game, fans get like that. Vandalizing your arch-rival school's statues. Using the kind of language you would never use in polite company. One University of Alabama fan was so mad over losing the "Iron Bowl" to arch-rival Auburn University that he poisoned a pair of trees in downtown Auburn that had become a focal point for the AU community.

So far, we have yet to see an NFL fan do anything like this. But we have seen gun massacres in America. Many of them. How long will it be before a fan takes his frustrations out on fans of his rival team? How long before such a fan drives into the parking lot, whips out an AR-15, and guns down tailgate partiers?

It hasn't happened. But don't tell me it can't.

Maybe the 100th Season is time to come to a painful conclusion: That the National Football League is doing more harm than good, and that the money being made off of it is no longer worth it.

Shut the NFL down. Celebrate this 100th Season, and then shut the League down. Let kids play football in high school and college. And then make them look for work. Let high schools and colleges be what they were always meant to be: Preparations for adult life.

This will not be a popular idea. Too many people have invested too much -- financially and/or emotionally -- to give up pro football.

But it needs to happen. For the players' sake. If your last game is a college bowl game when you're 22, you stand a much better chance of being able to think and move well in your 50s than you do if your last game is an NFL Playoff game when you're 32, or 37, or 40.

The NFL doesn't need to have a 200th Anniversary. Or a 150th. Or a 125th. Or even a 110th.

Let the NFL's 100th Anniversary be its last.

And, last season, both Conference Championship Games were ruined by the officials. It's bad enough that the Patriots unfairly got calls that allowed them to beat the Kansas City Chiefs, but the Los Angeles Rams got a call that, had it been made correctly, might have led to the New Orleans Saints winning. Result? The lowest-scoring Super Bowl ever, 13-3. Of course, the Patriots won.

NFL fans can't trust the team owners, or the officials, or the League office. And the players are getting killed. Literally. Not immediately: While there have been 5 deaths as a result of on-field play in the NFL's 100-year history (counting the AFL), there hasn't been one since Chuck Hughes of the Detroit Lions in 1971. But retired players are dying, and some not dying yet but suffering terribly, from the effects of their playing.

If team owners are so concerned over money, and protecting their assets, and treating the players as property (an idea that should have been shattered when baseball's reserve clause was struck down in 1975 -- 44 years ago), why don't they do more to protect those assets?

Which brings me back to the quarterback of the Colts. Not Johnny Unitas, their all-time greatest legend. Yes, kids, even over Peyton Manning. I mean the man who, until yesterday, was the current Colts quarterback, a man with the now-ironic name of Andrew Luck.

Coming out of Stanford University, Luck was the 1st pick of the 2012 NFL Draft. The Colts had that pick in that draft because Manning had sustained a neck injury and missed the entire 2011 season, resulting in the Colts going a League-worst 2-14. The Colts decided that, with Manning being 36, they'd be better off letting him go as a free agent, even though they would get nothing for him as they would in a trade, and drafting his replacement now.

It seemed to work well for both teams. Manning was sent to the Denver Broncos, whom he led to 2 Super Bowls, winning 1, before retiring. Meanwhile, Luck quarterbacked the Colts for 7 seasons, making the Playoffs 4 times, winning 2 AFC South Division titles, and making the 2014 AFC Championship Game -- the Deflategate Game. Despite injuries that plagued him in 2017 (he missed the entire season, and the team went 4-12) and 2018 (his delayed debut got them to 10-6 and a Playoff win away to Houston), he looked like he was headed for the Hall of Fame.

Yesterday, Luck held a press conference, and announced his retirement. He said, "I've been stuck in this process. I haven't been able to live the life I want to live. It's taken the joy out of this game. The only way forward for me is to remove myself from football. This is not an easy decision. It's the hardest decision of my life. But it is the right decision for me."

Andrew Luck is 29 years old. He could have become young Johnny Unitas. But he didn't want to become old Johnny Unitas.

*

This is what the National Football League does.

I don't blame the League for wanting to celebrate the hell out of its 100th Season. (It was founded on September 17, 1920, so this is the 100th Season, not the 100th Anniversary.) There is much to celebrate. Much good has been done by the teams and their players. Much joy has been brought to places where the game has been played.

Places like Los Angeles, Denver, San Diego, Tampa, Jacksonville and Phoenix, not previously thought of as "major league" or "big time," got that way through the NFL (or the AFL, which is now considered part of the NFL's history). Other places, such as Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Chicago, have had the successes of their football teams give them an emotional lift at times when, due to economic strife or municipal disharmony (or, in the case of Dallas, the stigma of having a President assassinated there), they really needed it. Buffalo and Los Angeles, which wouldn't seem to have much else in common, qualify on both counts.

But we now know things about football that we didn't know before. And then there are the things that we did know, but didn't want to admit. Football changes people. Not just those contractually involved. Fans change.

I attended 18 Phillies home games at Veterans Stadium. Aside from the stadium's bowl sometimes trapping the heat, the team often being bad, and that artificial turf being hideous, my experiences there were good ones. Only once did I ever have a problem with the home fans, and it was a minor, tolerable thing.

I attended 1 Eagles home game there. It was, if you'll pardon the pun, a whole different ballgame. Eagle fans have a reputation for being among the roughest in the League. It is deserved.

Compare Oakland fans for an A's game, where they're passionate, but mostly sane; and for a Raiders game, where they're animals.

Even in the college game, fans get like that. Vandalizing your arch-rival school's statues. Using the kind of language you would never use in polite company. One University of Alabama fan was so mad over losing the "Iron Bowl" to arch-rival Auburn University that he poisoned a pair of trees in downtown Auburn that had become a focal point for the AU community.

So far, we have yet to see an NFL fan do anything like this. But we have seen gun massacres in America. Many of them. How long will it be before a fan takes his frustrations out on fans of his rival team? How long before such a fan drives into the parking lot, whips out an AR-15, and guns down tailgate partiers?

It hasn't happened. But don't tell me it can't.

Maybe the 100th Season is time to come to a painful conclusion: That the National Football League is doing more harm than good, and that the money being made off of it is no longer worth it.

Shut the NFL down. Celebrate this 100th Season, and then shut the League down. Let kids play football in high school and college. And then make them look for work. Let high schools and colleges be what they were always meant to be: Preparations for adult life.

This will not be a popular idea. Too many people have invested too much -- financially and/or emotionally -- to give up pro football.

But it needs to happen. For the players' sake. If your last game is a college bowl game when you're 22, you stand a much better chance of being able to think and move well in your 50s than you do if your last game is an NFL Playoff game when you're 32, or 37, or 40.

The NFL doesn't need to have a 200th Anniversary. Or a 150th. Or a 125th. Or even a 110th.

Let the NFL's 100th Anniversary be its last.

No comments:

Post a Comment