I understand why the Jaguars wanted him. What I don't understand is why the Philadelphia Eagles got rid of him.

After all, he's the only quarterback ever to lead them to a Super Bowl win.

True, Carson Wentz is nearly 4 years younger. And he's pretty good. But he's not better, and he's injury-prone.

The Eagles may regret dumping the last quarterback to lead them to the NFL Championship.

Which is something they've actually done before.

You know the old saying: "Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me."

Top 10 Disses by Sports Organizations to Their Own Great Players

10. Nick Foles, Philadelphia Eagles, 2019. I have to list this one at the top (or the bottom, depending on how you look at it), because it just happened, and we haven't seen the repercussions just yet.

But when you didn't win the NFL Championship in 57 years -- the last time, it wasn't even called the Super Bowl yet -- and a guy leads you to it, and brings you to within 3 games of another, both times stepping in for a guy who got injured, why would you keep the guy who gets injured, and dump the guy who wins?

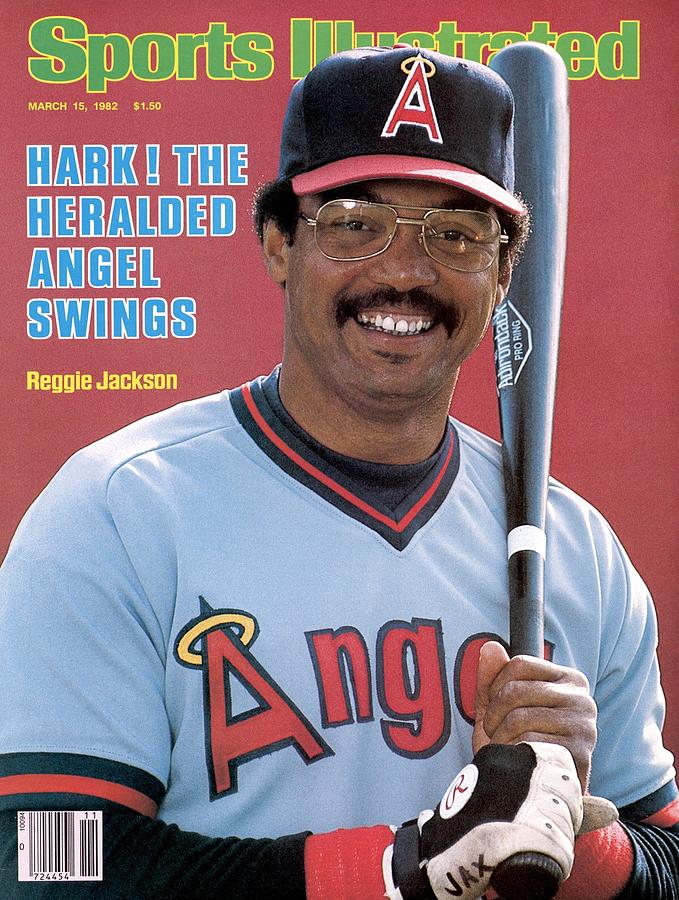

9. Reggie Jackson, New York Yankees, 1981. Reggie had a bad year at the plate in the worst possible year, the last year on his Yankee contract. Team owner George Steinbrenner chose not to sign Reggie to a new contract.

Reggie went to the California Angels (now the Los Angeles Angels), and returned to The Bronx with them on April 27, 1982. He'd gotten off to a lousy start, but on a rainy night, against Ron Guidry (a lefthander, one of the best of that era), he hit a home run. The Angels won the game, 3-1.

When Reggie swung, the fans were chanting, "Reg-GIE! Reg-GIE! Reg-GIE!" By the time he made his way around the bases and touched home plate, the chant had become, "Steinbrenner sucks!"

"Never... mind... the Queen. I... must embarrass... The Boss."

Reggie would help the Angels win the American League Western Division title in 1982 and 1986, and the Yankees didn't win another Pennant until 1996. George would later admit that letting Reggie go was his biggest mistake. They would eventually patch things up, and, since 1993, Reggie has worked in the Yankees' front office and been a uniformed spring training instructor. His Number 44 has been retired, and a Plaque in his honor stands in Monument Park.

8. Frank Robinson, Cincinnati Reds, 1965. When Gabe Paul was running the Reds, Branch Rickey, then general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates, wanted to acquire Robinson. Paul said, "I wouldn't give you Frank Robinson for your entire team." That entire team included 2 future Hall-of-Famers, Roberto Clemente and Bill Mazeroski; 2 future Most Valuable Players, Clemente and Dick Groat; and a future Cy Young Award winner, Vernon Law.

By 1965, following a National League Pennant for the Reds in 1961 (when Robinson was named NL MVP) and nearly 2 others in 1956 and 1964, Bill DeWitt, father of current St. Louis Cardinals owner Bill DeWitt Jr., was the owner of the Reds. He traded Frank Robinson to the Baltimore Orioles for Milt Pappas, Jack Baldschun and Dick Simpson. Baldschun and Simpson were throw-ins, designed to make the trade a 3-for-1, so it didn't look like the Reds were trading Robinson even-up for a single pitcher.

Yes, the Reds needed pitching. Yes, Pappas was a good pitcher. And if they had hung onto him longer -- say, through 1970, when he could have started for them in the World Series against Robinson and the Orioles -- the trade might not look so bad in hindsight.

Still, given Robinson's stats, why would the Reds trade him? DeWitt defended the trade, saying Robinson was "not a young 30." This eventually got twisted into the more familiar "an old 30."

DeWitt didn't realize that Robinson's best year was about to arrive: He won the Triple Crown in 1966, helping the Orioles win their 1st Pennant and their 1st World Series, and became the 1st man ever to win the MVP in both Leagues.

It would be many years, well into Robinson's career as MLB's 1st black manager, before he and the Reds organization made peace. He lived long enough to see them retire his Number 20 and dedicate a statue of him outside Great American Ballpark.

7. Carlton Fisk and Fred Lynn, Boston Red Sox, 1980. When Tom Yawkey owned the Red Sox from 1933 to 1976, he spent his vast fortune however he wanted, and gave his players nice salaries. When he died, his widow Jean inherited his fortune. She liked baseball, but liked Tom's money more. So she had her new general manager, Haywood Sullivan, lowball the players.

Unfortunately for Sox fans, Yawkey's death came just as free agency was taking shape in baseball. Big signings Bill Campbell (1976-77) and Mike Torrez (1977-78) didn't quite work out, and so Sullivan became reluctant to make any more big signings.

After the 1980 season, the contracts of catcher Fisk and center fielder Lynn, both among the best players in the game, and key figures on their 1975 team that won the Pennant and their 1977 and 1978 teams that just missed Division titles, expired. Sullivan mailed new contracts to them -- postmarked the day after the contractual deadline. In other words, they became free agents, not just because Sullivan and Mrs. Yawkey were cheap, but because Sullivan was spiteful.

Fisk signed with the Chicago White Sox, Lynn with the Angels. Lynn helped the Angels win the AL West in 1982. Fisk helped the ChiSox win the AL West in 1983, and ended up playing longer on the South Side than he did in the Back Bay. It would be 1986 before the Red Sox made the Playoffs again.

After Mrs. Yawkey's death, The Yawkey Trust straightened things out. Both players have been elected to the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame, and Fisk's Number 27 has been retired.

6. Eric Lindros, Philadelphia Flyers, 2000. In 1992, Eric Lindros made his NHL debut, with the Philadelphia Flyers. In 1994, just 21 years old, he was named their Captain. In 1995, he got them to the NHL Eastern Conference Finals, and won the Hart Memorial Trophy as MVP. In 1997, he got them to the Stanley Cup Finals, In 1998, still only 25, he was ranked 54th on The Hockey News' list of the 100 Greatest Hockey Players.

He looked like a sure bet to live up to his nickname: "The Next One," a reference to Wayne Gretzky being "The Great One." Along with Allen Iverson of the NBA's 76ers and Scott Rolen of baseball's Phillies, he seemed to be part of a triad that would make the early 21st Century a great time to be a sports fan in Philadelphia. The question wasn't if those guys would lead their teams to titles, but to how many.

As it turned out, only Rolen would ever win one -- and that would be in St. Louis. Things began to happen. In Lindros' case, it was injuries. It got to the point where one writer said, "This wasn't the next Gretzky. This wasn't even the first Lindros."

Flyer fans still love Bobby Clarke, their superstar captain of the 1970s. But they had no love for Bob Clarke, their general manager of the 1990s, even though it was the same guy, but with considerably less hair and considerably more wrinkles. Clarke -- one of the earliest athletes known to be playing with diabetes, and one of the top 5 players in the sport during the Nixon/Ford and Carter terms -- questioned Lindros' toughness.

Lindros' parents, who micromanaged his career, argued that the way the Flyer training staff handled an injury suffered in a game against the Nashville Predators late in the 1999 season nearly killed him. The doctors who treated him in Nashville backed them up. In 1999-2000, he suffered 2 concussions in the regular season, bringing his career total to 4, and he criticized Flyer trainers for improperly diagnosing him, and Flyer management for backing the trainers up.

Clarke decided that, rather than listening to his meal ticket, he should betray his status as a former player, and side with the organization, and punish him. A video was made of the Flyer equipment manager removing the C for Captain from Lindros' Number 88 jersey. The captaincy was handed to defenseman Eric Desjardins, a key figure in the Montreal Canadiens' 1993 Stanley Cup run, so if it had to go to someone else, that was a good choice. But stripping Lindros of the captaincy was a very petty thing to do, and unwarranted.

Lindros got clobbered by Scott Stevens in Game 7 of the Eastern Conference Finals, and the Flyers lost to the New Jersey Devils. When Lindros could have played again is a matter of debate, but he would never wear Flyer Orange & Black in another competitive game.

He wanted the Flyers to trade him to his hometown Toronto Maple Leafs. They refused. So he sat out the entire 2000-01 season -- probably the best thing he could have done for his brain. Finally, they traded him to the Rangers, and he spent 3 seasons with them. After missing the 2004-05 season due to the lockout, he finally signed with the Leafs, but only played 1 season with them, and 1 more season with the Dallas Stars before retiring in 2007.

He ended up scoring 372 goals, a lot more than most players ever get, but a lot fewer than he was expected to. He never got a 2nd shot at the Stanley Cup Finals.

By 2011, he and the Flyers, long since having kicked Clarke upstairs into an advisory role with little power, had made peace, and he and Clarke played together in an alumni game as part of the celebrations of the 2012 NHL Winter Classic between the Flyers and the Rangers. (Lindros was 38, Clarke was 62.) He was elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2016, and and Clarke played together in the Flyers' 50th Anniversary Alumni Game in 2017, and his Number 88 joined Clarke's 16 among the team's retired numbers in 2018.

5. Ted Lindsay, Detroit Red Wings, 1957. The 1956-57 season was be Lindsay's 9th as an NHL All-Star. But it would also be the end of the line for him with the Wings. He had become active in the recently-formed NHL Players Association, and league management did what it then did best: It overreacted. On July 23, Wings owner Bruce Norris traded Lindsay and goaltender Glenn Hall to the then-weak Chicago Blackhawks for Johnny Wilson, Forbes Kennedy, Hank Bassen and Bill Preston.

For Hall, the trade made sense: The Wings had Terry Sawchuk, the best goalie in the sport at the time, and Hall thrived in Chicago, becoming a Hall-of-Famer himself. But for Lindsay, it was punishment: Essentially, Norris, one of the biggest jerks in the history of sports team ownership (and that's saying something), was telling him, "I consider union activism so much of a personal insult that I'm sending you to a crap team for 4 nobodies." (Wilson was a decent left wing, but center Kennedy and goalie Bassen were career backups, and Preston never played a shift in the NHL.)

It got worse: Jack Adams, general manager of the Wings, told the media that Lindsay had made defamatory comments against his old team, and showed them a fake contract, with a salary far higher than he had actually been paid.

Lindsay sued. The case could have broken the NHL wide open, especially since the Norris family also held the mortgages on Chicago Stadium, the Boston Garden, and even that era's Madison Square Garden -- effectively making Bruce Norris the most powerful American in hockey. Norris' lawyers told him to settle. In February 1958, he did: Most of the union's demands were met, and the accusations against Lindsay were retracted.

Norris sold the Wings in 1982. They didn't win the Stanley Cup again until 1997. Of course, it didn't help that they later also screwed over Lindsay's pal on the "Production Line":

4. Gordie Howe, Detroit Red Wings, 1973. After the 1971 season, his record 25th in the NHL, Gordie was convinced by a nagging wrist injury to retire at age 43. He was given a job in the Wings' front office, but, essentially, he was just a schmoozer, shaking hands with corporate clients at the Olympia, and allowing the Wings to put his magic name on their corporate letterhead.

Gordie grumbled about not having any actual input in the running of the organization. He wasn't the head coach, or an assistant coach, or the general manager, or the director of scouting, or anything of substance. In his words, he was "vice president in charge of paper clips."

The World Hockey Association launched for the 1972-73 season. Bill Dineen, a teammate of Gordie's on the '54 and '55 Cup winners, was named head coach of the WHA's Houston Aeros; another '55 (but not '54) teammate, Larry Hillman, was his assistant. In the 1973 WHA Draft, Dineen took Gordie's sons Mark and Marty.

To help the WHA get better publicity -- they'd already gotten Bobby Hull onto the Winnipeg Jets -- Dineen asked Gordie to come out of retirement. After talking to his wife Colleen, who was also his agent (a very rare thing for a woman at the time), he was willing to get surgery on his troubled wrist, and give it a shot.

Bruce Norris told the Howe family that if Gordie quit the Wings' front office and went to "the rebel league," not only would he be blackballed from the NHL, never to work in it again in any capacity, but that Mark and Marty would also be blackballed -- and since they were players just starting out, this would affect them much more.

In other words, he gave Gordie and Colleen an anti-incentive that would have hurt them personally much more than his own blackballing would have hurt Gordie, personally or professionally. It may not be the biggest dick move in the history of sports, but it's the best-known dick move in NHL history.

And it backfired. Few decisions in the history of sports have backfired this much. Gordie called Norris' bluff. He and his sons led the Aeros to the 1974 and 1975 WHA Championships. Gordie was named WHA MVP at age 45. Their MVP trophy was renamed the Gordie Howe Trophy. They got back to the Finals in 1976. Desperate for cash, the Aeros sold the Howes to the New England Whalers.

When the merger between the leagues happened, the Whalers were one of the teams admitted to the NHL. The other owners knew that Norris was as short on cash as the WHA owners were, and they set aside his unofficial ban, and cleared Gordie's Wings contract. The 1980 NHL All-Star Game was held in Detroit, and Gordie got a standing ovation that went on and on and on. I wonder if how bad it felt for Norris was more than how good it felt for Gordie. This was a bigger insult from fans to team owner than even the 1982 Yankee Fans gave Steinbrenner after Reggie's return homer.

Mike Ilitch, who bought the Wings from the Norris family, repaired relationships with several stars, including Howe, putting his Number 9 back in the rafters, and Lindsay, retiring his Number 7. He put statues of both at Joe Louis Arena, and they've been moved to Little Caesars Arena.

3. Jackie Robinson, Brooklyn Dodgers, 1956. Jackie had been brought to the Dodgers by team president and part-owner Branch Rickey. By being the team that reintegrated Major League Baseball, the Dodgers reached a special place in American lore, and Jackie Robinson was the reason why.

In 1950, Rickey was bought out by another part-owner, Walter O'Malley. O'Malley hated Rickey (and the feeling was mutual), and didn't trust any of Rickey's people, including Jackie. In 1954, O'Malley hired Walter Alston as manager, and while Alston's commitment to treating his players fairly regardless of race has never been seriously questioned, he seemed to be under O'Malley's orders to let Jackie know that his time was running out. Although the Dodgers finally won the World Series in 1955, Alston did not play Jackie in the deciding Game 7 on October 4.

In all fairness, Jackie had put on some weight, and his batting average dropped from .311 (which turned out to be his career average) in 1954 to .256 in '55. His last hurrah was driving in the winning run in the bottom of the 10th inning in Game 6 of the 1956 World Series, but in Game 7, on October 10, 1956, the Yankees shelled the Dodgers, 9-0. Jackie's last at-bat was the last out of the game, a strikeout, but Yogi dropped the 3rd strike. Remembering the Mickey Owen play from the 1941 Series between the teams, Jackie took off for 1st; but Yogi remembered it as well, got the ball, and threw him out.

On December 13, O'Malley traded Jackie to the arch-rival Giants for Dick Littlefield (you don't need to know anything else about him) and $30,000. Jackie's response to this F.U. from O'Malley was to F.U. him right back: He retired rather than report to the enemy. He had played 10 seasons, and was about to turn 38.

In 1972, with O'Malley still in charge, the Los Angeles edition of the Dodgers retired Jackie's Number 42. Later that year, Jackie died from complications of diabetes. A statue of Jackie now stands outside Dodger Stadium.

2. Norm Van Brocklin, Philadelphia Eagles, 1960. He was the 1st quarterback to lead to different teams to the NFL Championship: The 1951 Los Angeles Rams and the 1960 Philadelphia Eagles. This feat would not be matched until Peyton Manning did for the Indianapolis Colts and the Denver Broncos, in the 2015 season.

8. Frank Robinson, Cincinnati Reds, 1965. When Gabe Paul was running the Reds, Branch Rickey, then general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates, wanted to acquire Robinson. Paul said, "I wouldn't give you Frank Robinson for your entire team." That entire team included 2 future Hall-of-Famers, Roberto Clemente and Bill Mazeroski; 2 future Most Valuable Players, Clemente and Dick Groat; and a future Cy Young Award winner, Vernon Law.

By 1965, following a National League Pennant for the Reds in 1961 (when Robinson was named NL MVP) and nearly 2 others in 1956 and 1964, Bill DeWitt, father of current St. Louis Cardinals owner Bill DeWitt Jr., was the owner of the Reds. He traded Frank Robinson to the Baltimore Orioles for Milt Pappas, Jack Baldschun and Dick Simpson. Baldschun and Simpson were throw-ins, designed to make the trade a 3-for-1, so it didn't look like the Reds were trading Robinson even-up for a single pitcher.

Yes, the Reds needed pitching. Yes, Pappas was a good pitcher. And if they had hung onto him longer -- say, through 1970, when he could have started for them in the World Series against Robinson and the Orioles -- the trade might not look so bad in hindsight.

Still, given Robinson's stats, why would the Reds trade him? DeWitt defended the trade, saying Robinson was "not a young 30." This eventually got twisted into the more familiar "an old 30."

DeWitt didn't realize that Robinson's best year was about to arrive: He won the Triple Crown in 1966, helping the Orioles win their 1st Pennant and their 1st World Series, and became the 1st man ever to win the MVP in both Leagues.

It would be many years, well into Robinson's career as MLB's 1st black manager, before he and the Reds organization made peace. He lived long enough to see them retire his Number 20 and dedicate a statue of him outside Great American Ballpark.

7. Carlton Fisk and Fred Lynn, Boston Red Sox, 1980. When Tom Yawkey owned the Red Sox from 1933 to 1976, he spent his vast fortune however he wanted, and gave his players nice salaries. When he died, his widow Jean inherited his fortune. She liked baseball, but liked Tom's money more. So she had her new general manager, Haywood Sullivan, lowball the players.

Unfortunately for Sox fans, Yawkey's death came just as free agency was taking shape in baseball. Big signings Bill Campbell (1976-77) and Mike Torrez (1977-78) didn't quite work out, and so Sullivan became reluctant to make any more big signings.

After the 1980 season, the contracts of catcher Fisk and center fielder Lynn, both among the best players in the game, and key figures on their 1975 team that won the Pennant and their 1977 and 1978 teams that just missed Division titles, expired. Sullivan mailed new contracts to them -- postmarked the day after the contractual deadline. In other words, they became free agents, not just because Sullivan and Mrs. Yawkey were cheap, but because Sullivan was spiteful.

Fisk signed with the Chicago White Sox, Lynn with the Angels. Lynn helped the Angels win the AL West in 1982. Fisk helped the ChiSox win the AL West in 1983, and ended up playing longer on the South Side than he did in the Back Bay. It would be 1986 before the Red Sox made the Playoffs again.

After Mrs. Yawkey's death, The Yawkey Trust straightened things out. Both players have been elected to the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame, and Fisk's Number 27 has been retired.

6. Eric Lindros, Philadelphia Flyers, 2000. In 1992, Eric Lindros made his NHL debut, with the Philadelphia Flyers. In 1994, just 21 years old, he was named their Captain. In 1995, he got them to the NHL Eastern Conference Finals, and won the Hart Memorial Trophy as MVP. In 1997, he got them to the Stanley Cup Finals, In 1998, still only 25, he was ranked 54th on The Hockey News' list of the 100 Greatest Hockey Players.

He looked like a sure bet to live up to his nickname: "The Next One," a reference to Wayne Gretzky being "The Great One." Along with Allen Iverson of the NBA's 76ers and Scott Rolen of baseball's Phillies, he seemed to be part of a triad that would make the early 21st Century a great time to be a sports fan in Philadelphia. The question wasn't if those guys would lead their teams to titles, but to how many.

As it turned out, only Rolen would ever win one -- and that would be in St. Louis. Things began to happen. In Lindros' case, it was injuries. It got to the point where one writer said, "This wasn't the next Gretzky. This wasn't even the first Lindros."

Flyer fans still love Bobby Clarke, their superstar captain of the 1970s. But they had no love for Bob Clarke, their general manager of the 1990s, even though it was the same guy, but with considerably less hair and considerably more wrinkles. Clarke -- one of the earliest athletes known to be playing with diabetes, and one of the top 5 players in the sport during the Nixon/Ford and Carter terms -- questioned Lindros' toughness.

Lindros' parents, who micromanaged his career, argued that the way the Flyer training staff handled an injury suffered in a game against the Nashville Predators late in the 1999 season nearly killed him. The doctors who treated him in Nashville backed them up. In 1999-2000, he suffered 2 concussions in the regular season, bringing his career total to 4, and he criticized Flyer trainers for improperly diagnosing him, and Flyer management for backing the trainers up.

Clarke decided that, rather than listening to his meal ticket, he should betray his status as a former player, and side with the organization, and punish him. A video was made of the Flyer equipment manager removing the C for Captain from Lindros' Number 88 jersey. The captaincy was handed to defenseman Eric Desjardins, a key figure in the Montreal Canadiens' 1993 Stanley Cup run, so if it had to go to someone else, that was a good choice. But stripping Lindros of the captaincy was a very petty thing to do, and unwarranted.

Lindros got clobbered by Scott Stevens in Game 7 of the Eastern Conference Finals, and the Flyers lost to the New Jersey Devils. When Lindros could have played again is a matter of debate, but he would never wear Flyer Orange & Black in another competitive game.

He wanted the Flyers to trade him to his hometown Toronto Maple Leafs. They refused. So he sat out the entire 2000-01 season -- probably the best thing he could have done for his brain. Finally, they traded him to the Rangers, and he spent 3 seasons with them. After missing the 2004-05 season due to the lockout, he finally signed with the Leafs, but only played 1 season with them, and 1 more season with the Dallas Stars before retiring in 2007.

He ended up scoring 372 goals, a lot more than most players ever get, but a lot fewer than he was expected to. He never got a 2nd shot at the Stanley Cup Finals.

By 2011, he and the Flyers, long since having kicked Clarke upstairs into an advisory role with little power, had made peace, and he and Clarke played together in an alumni game as part of the celebrations of the 2012 NHL Winter Classic between the Flyers and the Rangers. (Lindros was 38, Clarke was 62.) He was elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2016, and and Clarke played together in the Flyers' 50th Anniversary Alumni Game in 2017, and his Number 88 joined Clarke's 16 among the team's retired numbers in 2018.

5. Ted Lindsay, Detroit Red Wings, 1957. The 1956-57 season was be Lindsay's 9th as an NHL All-Star. But it would also be the end of the line for him with the Wings. He had become active in the recently-formed NHL Players Association, and league management did what it then did best: It overreacted. On July 23, Wings owner Bruce Norris traded Lindsay and goaltender Glenn Hall to the then-weak Chicago Blackhawks for Johnny Wilson, Forbes Kennedy, Hank Bassen and Bill Preston.

For Hall, the trade made sense: The Wings had Terry Sawchuk, the best goalie in the sport at the time, and Hall thrived in Chicago, becoming a Hall-of-Famer himself. But for Lindsay, it was punishment: Essentially, Norris, one of the biggest jerks in the history of sports team ownership (and that's saying something), was telling him, "I consider union activism so much of a personal insult that I'm sending you to a crap team for 4 nobodies." (Wilson was a decent left wing, but center Kennedy and goalie Bassen were career backups, and Preston never played a shift in the NHL.)

It got worse: Jack Adams, general manager of the Wings, told the media that Lindsay had made defamatory comments against his old team, and showed them a fake contract, with a salary far higher than he had actually been paid.

Lindsay sued. The case could have broken the NHL wide open, especially since the Norris family also held the mortgages on Chicago Stadium, the Boston Garden, and even that era's Madison Square Garden -- effectively making Bruce Norris the most powerful American in hockey. Norris' lawyers told him to settle. In February 1958, he did: Most of the union's demands were met, and the accusations against Lindsay were retracted.

Norris sold the Wings in 1982. They didn't win the Stanley Cup again until 1997. Of course, it didn't help that they later also screwed over Lindsay's pal on the "Production Line":

4. Gordie Howe, Detroit Red Wings, 1973. After the 1971 season, his record 25th in the NHL, Gordie was convinced by a nagging wrist injury to retire at age 43. He was given a job in the Wings' front office, but, essentially, he was just a schmoozer, shaking hands with corporate clients at the Olympia, and allowing the Wings to put his magic name on their corporate letterhead.

Gordie grumbled about not having any actual input in the running of the organization. He wasn't the head coach, or an assistant coach, or the general manager, or the director of scouting, or anything of substance. In his words, he was "vice president in charge of paper clips."

The World Hockey Association launched for the 1972-73 season. Bill Dineen, a teammate of Gordie's on the '54 and '55 Cup winners, was named head coach of the WHA's Houston Aeros; another '55 (but not '54) teammate, Larry Hillman, was his assistant. In the 1973 WHA Draft, Dineen took Gordie's sons Mark and Marty.

To help the WHA get better publicity -- they'd already gotten Bobby Hull onto the Winnipeg Jets -- Dineen asked Gordie to come out of retirement. After talking to his wife Colleen, who was also his agent (a very rare thing for a woman at the time), he was willing to get surgery on his troubled wrist, and give it a shot.

Bruce Norris told the Howe family that if Gordie quit the Wings' front office and went to "the rebel league," not only would he be blackballed from the NHL, never to work in it again in any capacity, but that Mark and Marty would also be blackballed -- and since they were players just starting out, this would affect them much more.

In other words, he gave Gordie and Colleen an anti-incentive that would have hurt them personally much more than his own blackballing would have hurt Gordie, personally or professionally. It may not be the biggest dick move in the history of sports, but it's the best-known dick move in NHL history.

And it backfired. Few decisions in the history of sports have backfired this much. Gordie called Norris' bluff. He and his sons led the Aeros to the 1974 and 1975 WHA Championships. Gordie was named WHA MVP at age 45. Their MVP trophy was renamed the Gordie Howe Trophy. They got back to the Finals in 1976. Desperate for cash, the Aeros sold the Howes to the New England Whalers.

When the merger between the leagues happened, the Whalers were one of the teams admitted to the NHL. The other owners knew that Norris was as short on cash as the WHA owners were, and they set aside his unofficial ban, and cleared Gordie's Wings contract. The 1980 NHL All-Star Game was held in Detroit, and Gordie got a standing ovation that went on and on and on. I wonder if how bad it felt for Norris was more than how good it felt for Gordie. This was a bigger insult from fans to team owner than even the 1982 Yankee Fans gave Steinbrenner after Reggie's return homer.

Mike Ilitch, who bought the Wings from the Norris family, repaired relationships with several stars, including Howe, putting his Number 9 back in the rafters, and Lindsay, retiring his Number 7. He put statues of both at Joe Louis Arena, and they've been moved to Little Caesars Arena.

3. Jackie Robinson, Brooklyn Dodgers, 1956. Jackie had been brought to the Dodgers by team president and part-owner Branch Rickey. By being the team that reintegrated Major League Baseball, the Dodgers reached a special place in American lore, and Jackie Robinson was the reason why.

In 1950, Rickey was bought out by another part-owner, Walter O'Malley. O'Malley hated Rickey (and the feeling was mutual), and didn't trust any of Rickey's people, including Jackie. In 1954, O'Malley hired Walter Alston as manager, and while Alston's commitment to treating his players fairly regardless of race has never been seriously questioned, he seemed to be under O'Malley's orders to let Jackie know that his time was running out. Although the Dodgers finally won the World Series in 1955, Alston did not play Jackie in the deciding Game 7 on October 4.

In all fairness, Jackie had put on some weight, and his batting average dropped from .311 (which turned out to be his career average) in 1954 to .256 in '55. His last hurrah was driving in the winning run in the bottom of the 10th inning in Game 6 of the 1956 World Series, but in Game 7, on October 10, 1956, the Yankees shelled the Dodgers, 9-0. Jackie's last at-bat was the last out of the game, a strikeout, but Yogi dropped the 3rd strike. Remembering the Mickey Owen play from the 1941 Series between the teams, Jackie took off for 1st; but Yogi remembered it as well, got the ball, and threw him out.

On December 13, O'Malley traded Jackie to the arch-rival Giants for Dick Littlefield (you don't need to know anything else about him) and $30,000. Jackie's response to this F.U. from O'Malley was to F.U. him right back: He retired rather than report to the enemy. He had played 10 seasons, and was about to turn 38.

In 1972, with O'Malley still in charge, the Los Angeles edition of the Dodgers retired Jackie's Number 42. Later that year, Jackie died from complications of diabetes. A statue of Jackie now stands outside Dodger Stadium.

2. Norm Van Brocklin, Philadelphia Eagles, 1960. He was the 1st quarterback to lead to different teams to the NFL Championship: The 1951 Los Angeles Rams and the 1960 Philadelphia Eagles. This feat would not be matched until Peyton Manning did for the Indianapolis Colts and the Denver Broncos, in the 2015 season.

Van Brocklin knew he wanted to retire at the end of the 1960 season, so the Championship Game, a 17-13 win over the Green Bay Packers, would be his last game. He also knew that Buck Shaw, the head coach of the Eagles, was also retiring. Van Brocklin thought he had the inside track to being named the new head coach. After all, he had proven himself as a leader.

Instead, the Eagles hired Nick Skorich as their head coach. He led them for 3 seasons, dropping from 10-2 in 1960, the last year of the 12-game schedule, to 10-4 and 2nd place in the NFL Eastern Division in the 1st year of the 14-game schedule -- so far, not bad -- to a disastrous 3-10-1 in 1962 and 2-10-2 in 1963. It was the start of a 57-year title drought for the Broad Street Birds.

Van Brocklin did get a job offer, though, as the 1st head coach of the expansion Minnesota Vikings. He didn't do much better over those 3 years than did Skorich in Philadelphia, but did get the Vikes to 8-5-1 by 1964.

He later coached the Atlanta Falcons as well, but in 13 seasons as an NFL head coach, he was 37-49-3, with only 3 winning season: 1964 with Minnesota, 7-6-1 with the '71 Falcons, and 9-5 with the '73 Falcons. After losing 6 of his 1st 8 in 1974, he was fired, and never coached again. He was only 52.

If the Eagles had hired Van Brocklin, would they have done better? It's hard to say, as the New York Giants won 6 Division titles in 8 years, and by the time the Giants got old, the Cleveland Browns got good again.

But they certainly would have been better off with Van Brocklin instead of Skorich and his even worse successor, Joe Kuharich, the man who traded Sonny Jurgensen to Washington for Norm Snead, one of the worst trades in the history of the NFL.

It took the Eagles 57 years to win another title. Could it be called The Curse of the Dutchman? At any rate, there was never a reunion of the 1960 Eagles until the 25th Anniversary, 1985, 2 years after Van Brocklin's death. He was a charter inductee into the Eagles Hall of Fame in 1987, but his Number 11 has not been retired.

1. Tom Seaver, New York Mets, 1977. The man that Met fans called "Tom Terrific" and "The Franchise" thought he was underpaid. Given that he was the Mets' biggest drawing card, he was right: In the 8 home games that he started, the Mets got an average per-game attendance of 23,257; the 17 home games he didn't start, they averaged 11,913, about half as much.

Seaver wanted to remain a Met for the rest of his career, but wanted more money and over a longer period of time, guaranteed. He decided to go over the head of team president M. Donald Grant, and asked owner Lorinda de Roulet for a contract extension. She agreed to it. No problem, right?

Wrong: Grant acted as though he was the true owner of the Mets, and took this as a grave personal insult. (Well, maybe it was, but he deserved it.) Grant went to Dick Young, longtime baseball columnist for the Daily News. Once a liberal crusader who stood up for Jackie Robinson, Young was now 59 years old. Years of hard drinking had lined his face and turned his hair stark white. He had become embittered and conservative, as he saw what he called "my America" fading away.

Aside from possibly Whitey Ford, Seaver was the best pitcher that Young would ever see for a New York team, but he was now tight with Grant. Grant asked him to write a column smearing Seaver. Young didn't need much convincing. He probably traded it for a drink. He was probably happy to do it.

Here is a summary of the most infamous sports column in the history of New York newspapers, from the Daily News of June 15, 1977 -- at the time, June 15 was the trading deadline in MLB:

Van Brocklin did get a job offer, though, as the 1st head coach of the expansion Minnesota Vikings. He didn't do much better over those 3 years than did Skorich in Philadelphia, but did get the Vikes to 8-5-1 by 1964.

He later coached the Atlanta Falcons as well, but in 13 seasons as an NFL head coach, he was 37-49-3, with only 3 winning season: 1964 with Minnesota, 7-6-1 with the '71 Falcons, and 9-5 with the '73 Falcons. After losing 6 of his 1st 8 in 1974, he was fired, and never coached again. He was only 52.

If the Eagles had hired Van Brocklin, would they have done better? It's hard to say, as the New York Giants won 6 Division titles in 8 years, and by the time the Giants got old, the Cleveland Browns got good again.

But they certainly would have been better off with Van Brocklin instead of Skorich and his even worse successor, Joe Kuharich, the man who traded Sonny Jurgensen to Washington for Norm Snead, one of the worst trades in the history of the NFL.

It took the Eagles 57 years to win another title. Could it be called The Curse of the Dutchman? At any rate, there was never a reunion of the 1960 Eagles until the 25th Anniversary, 1985, 2 years after Van Brocklin's death. He was a charter inductee into the Eagles Hall of Fame in 1987, but his Number 11 has not been retired.

1. Tom Seaver, New York Mets, 1977. The man that Met fans called "Tom Terrific" and "The Franchise" thought he was underpaid. Given that he was the Mets' biggest drawing card, he was right: In the 8 home games that he started, the Mets got an average per-game attendance of 23,257; the 17 home games he didn't start, they averaged 11,913, about half as much.

Seaver wanted to remain a Met for the rest of his career, but wanted more money and over a longer period of time, guaranteed. He decided to go over the head of team president M. Donald Grant, and asked owner Lorinda de Roulet for a contract extension. She agreed to it. No problem, right?

Wrong: Grant acted as though he was the true owner of the Mets, and took this as a grave personal insult. (Well, maybe it was, but he deserved it.) Grant went to Dick Young, longtime baseball columnist for the Daily News. Once a liberal crusader who stood up for Jackie Robinson, Young was now 59 years old. Years of hard drinking had lined his face and turned his hair stark white. He had become embittered and conservative, as he saw what he called "my America" fading away.

Aside from possibly Whitey Ford, Seaver was the best pitcher that Young would ever see for a New York team, but he was now tight with Grant. Grant asked him to write a column smearing Seaver. Young didn't need much convincing. He probably traded it for a drink. He was probably happy to do it.

Here is a summary of the most infamous sports column in the history of New York newspapers, from the Daily News of June 15, 1977 -- at the time, June 15 was the trading deadline in MLB:

In a way, Tom Seaver is like Walter O’Malley. Both are very good at what they do. Both are very deceptive in what they say. Both are very greedy.

Greed is greed, whether it is manifested by an owner or a ballplayer...

Tom Seaver is after more money. He wants to break his contract with the Mets. “Renegotiate” is the pretty word he used for it in this time of pretty words.

So, Tom Seaver said, over and over, that the Mets were not competitive in the free agent field. He said the front office was not spending money the way it should. He made it appear that he wanted the money to be spent on others, but really he wanted it to be spent on him. He talked ideals, but actually he was talking hard cash.

Like O’Malley, Tom Seaver couldn’t say that out loud. How would it sound for Tom Terrific, All-American boy, to disavow a contract he had signed in good faith?...

“Tom, we can’t do that,” said Grant. “I have a board of directors to account for. Were you happy when you signed your contract?”

“Yes, I was, but things have changed.”

“You asked for more money than had ever been paid to any pitcher, and you got it.”

“That’s not so anymore,” said Seaver.

“Who gets more?”

“Tiant, Ryan, Tanana.”

“I don’t know about that,” said Grant, “but it was you who opted for a three year contract. If we renegotiate for you, we would have every player on the team in the office. Please see the light of day. I beg you to reconsider and be the Tom Seaver happy to play with the Mets.”

“You want me to be happy at your terms.”

“Yes, and you want to be happy only on your terms, and that’s a standoff. I have told you 10 times we don’t want to trade you. Of the cities you prefer, we have our best offer from Cincinnati. If that can crystallize, we’ll make it.”

Tom Seaver’s base pay is $225,000, and he could do $250,000 with a good year. Luis Tiant does not make $225,000. Frank Tanana, by threatening to play out his option, received a $1 million signing bonus from Gene Autry, but his base salary of $200,000 is below Seaver’s. Nolan Ryan is getting more now than Seaver, and that galls Tom because Nancy Seaver and Ruth Ryan are very friendly and Tom Seaver long has treated Nolan Ryan like a little brother.

It comes down to this: Tom Seaver is jealous of those who had the guts to play out their option or used the threat of playing it out as leverage for a big raise — while he was snug behind a three-year contract of his choosing. He talks of being treated like a man. A man lives up to his contract...

Young had lied through his dentures about what Seaver said, and his reasons for wanting to renegotiate. That was bad enough. But he had also brought Seaver's wife into the lies -- and Ryan's wife, too.

Young wrote about what "a man" does. A man may disagree with another man, but a man does not bring the other man's family into it. That is a line that a man does not cross. Ever.

You got a problem with someone? Fine. But leave the family out of it. By playing Major League Baseball, Tom Seaver had made himself a public figure. Nancy Seaver was not a public figure until Dick Young made her one, and for what? Selling a few newspapers, and doing his pal M. Donald Grant a big fat favor.

"That Young column was the straw that broke the back," Seaver told the Daily News in 2007, on the 30th Anniversary. "Bringing your family into it, with no truth whatsoever to what he wrote. I could not abide by that. I had to go."

Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon bought the team in 1980, and brought Seaver back in 1983 -- and then lost him due to a bureaucratic mixup. They retired his Number 41 in 1988, elected him to their team Hall of Fame, and invited him to throw out the last ball at Shea Stadium in 2008 and the first ball at Citi Field in 2009 and at the 2013 All-Star Game. Next year, a statue of him will be dedicated outside Citi Field.

*

So, out of the 9 earliest of these 10 stories, there were eventually happy endings with 8 of them. But the 1 that isn't is that of Norm Van Brocklin -- also an Eagles quarterback. Is that a bad sign for Foles?

It's highly unlikely that there will be any long-term feud between them. Most likely, there will be a reunion, if not while Foles is an active player.

Young wrote about what "a man" does. A man may disagree with another man, but a man does not bring the other man's family into it. That is a line that a man does not cross. Ever.

You got a problem with someone? Fine. But leave the family out of it. By playing Major League Baseball, Tom Seaver had made himself a public figure. Nancy Seaver was not a public figure until Dick Young made her one, and for what? Selling a few newspapers, and doing his pal M. Donald Grant a big fat favor.

"That Young column was the straw that broke the back," Seaver told the Daily News in 2007, on the 30th Anniversary. "Bringing your family into it, with no truth whatsoever to what he wrote. I could not abide by that. I had to go."

Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon bought the team in 1980, and brought Seaver back in 1983 -- and then lost him due to a bureaucratic mixup. They retired his Number 41 in 1988, elected him to their team Hall of Fame, and invited him to throw out the last ball at Shea Stadium in 2008 and the first ball at Citi Field in 2009 and at the 2013 All-Star Game. Next year, a statue of him will be dedicated outside Citi Field.

*

So, out of the 9 earliest of these 10 stories, there were eventually happy endings with 8 of them. But the 1 that isn't is that of Norm Van Brocklin -- also an Eagles quarterback. Is that a bad sign for Foles?

It's highly unlikely that there will be any long-term feud between them. Most likely, there will be a reunion, if not while Foles is an active player.

No comments:

Post a Comment