With his death, the slogan "Justice for the 96" and the hashtag #JFT96 became "Justice for the 97" and #JFT97. And that total of 97 does not count the people who couldn't handle the physical and emotional difficulties that they, or their loved ones, suffered from that day, and later took their own lives.

April 15, 1989, 30 years ago today: A terrible mistake in opening the wrong gate leads to the deaths of 96 people, and injuries to hundreds of others, at Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield, England, at the start of an FA Cup Semifinal, on neutral ground, between soccer teams Liverpool and Nottingham Forest. Most of those hurt were Liverpool fans.

It was a Saturday, and that night, on ABC World News Tonight, the story was shown. It wasn't the first awful soccer-crowd story to be shown on American TV news, so, like a lot of Americans, I just thought, "Well, there go those English soccer hooligans again, screwing things up for everybody."

I didn't get it. At all.

I was 19, not a little kid anymore. I should have known better.

You know who else should have known better? ABC. And NBC, and CBS, and CNN, and ESPN, and Time magazine, and its subsidiary Sports Illustrated, and other American media outlets. The story did not end that day. It went on and on.

But the American media figured, "It's not an American story, there were no Americans involved, so, now that we've reported it once, we should no longer care. Besides, it's not a sport Americans even care about. Let's move on."

I never heard another word about Hillsborough until 2008, when I plunged into soccer, finding, literally, a whole world of stories that I didn't know.

And I learned things about the Hillsborough Disaster that the American media either got wrong, or did say well enough, and then ignored.

Which still gives them higher moral ground than the English media, which behaved despicably in the aftermath.

*

First, some background. The Football Association Cup (the FA Cup) is one of the oldest continually-operating sports competitions in the world. Every soccer (football) club in England and Wales is eligible -- 736 of them entered the 2018-19 edition.

There are qualifying rounds before they get down to the "rounds proper":

* First Round, with 80 teams, on the 2nd weekend of November. Teams in the 3rd and 4th Divisions of English football (currently named League One and League Two) get a bye into this round.

* Second Round, with 40 teams, on the 1st weekend of December.

* Third Round, with 64 teams, on the 1st weekend of January (unless January 1 falls on a weekend, then it's pushed back a week). Teams in the 1st and 2nd Divisions (currently named the Premier League and The Championship) get a bye into this round.

* Fourth Round, with 32 teams, on the 4th weekend of January.

* Fifth Round, with 16 teams, on the 2nd weekend of February.

* Sixth Round, or Quarterfinals, on the 1st weekend of March.

* Semifinals, on the 2nd weekend of April.

* Final, on the 3rd Saturday in May.

Every round until the Quarterfinals is played at the stadium, or "ground," of one of the competing teams in the match. If it ends in a tie, or "draw," a replay is required, at the other team's ground.

The Semifinals, historically, have been played at neutral sites, usually in one of England's larger cities and in one of its larger stadiums. London's Highbury (Arsenal, North), White Hart Lane (Tottenham, also North) and Stamford Bridge (Chelsea, West) have hosted. So did both of the old Manchester stadiums, Old Trafford (Manchester United) and the now-demolished Maine Road (former home of Manchester City).

Villa Park in Birmingham (home of Aston Villa) was a frequent site, and so was Hillsborough Stadium, home of Sheffield Wednesday. That club was so named because the cricket club they were founded as played their matches on Wednesdays.

The Final, historically, has been played at England's national stadium, Wembley Stadium in London since 1923, opening for a Final, won by Bolton Wanderers of Lancashire over West Ham United of East London. After 2000, when the old Wembley was demolished to make way for the new one, it was held at the biggest remaining stadium in Britain, the Millennium Stadium in Cardiff, Wales. The new Wembley opened in 2007, and Chelsea of West London won the first Cup Final there. Since 2008, the Semifinals have also been held at Wembley, one on Saturday, the other on Sunday.

Owlerton Stadium opened in the Owlerton section of Sheffield in 1899 -- and The Wednesday became nicknamed the Owls because of the location. In 1914, it was renamed Hillsborough Stadium. By 1966, it had been mostly modernized, with a capacity of 34,000, was significantly lauded for this, and was selected as one of the venues for England's hosting of that year's World Cup.

But not all was as it seemed. The rise of hooliganism in the late 1960s led to crowd control measures that turned dangerous. And with the end sections of stadiums, behind the goals, nearly all being "terraces" -- stepped areas with railings but no seats, where fans would stand and watch the game -- fans would run in for good vantage points, leading to fans getting knocked over onto the field (or "pitch," as they'd say over there). With standees, Hillsborough could now hold over 55,000.

In 1973, in miserable weather (even as far north as Yorkshire, it shouldn't have been snowing and sleeting on an April 17), Arsenal played North-East club Sunderland at Hillsborough. Arsenal fans were put into the West Stand, a.k.a. the Leppings Lane End. There was a rush into the End, and it spilled over onto the pitch. No major injuries, but it was a warning sign.

(Sunderland, then in the old Division Two, pulled off a shocker, beating 1971 League and Cup "Double" winners Arsenal, and then upsetting defending Cup holders Leeds United in the Final.)

In 1981, it got worse for Arsenal's North London arch-rivals, Tottenham Hotspur (a.k.a. Spurs). They reached the Semifinal, and were assigned to play Wolverhampton Wanderers (a.k.a. Wolves), at Hillsborough. The Spurs fans were also put into the Leppings Lane End, through the concourses that led to the various pens behind the goal. There was a crush, and as one Spurs fans' site (written by a man whose name I couldn't find) puts it:

People were crushed not because of surging support or bad behaviour, but simply because the spaces between the large metal fences were too small. Indeed there was a feeling even before then, without benefit of hindsight, that the supposed capacity of Leppings Lane was overstated and unsafe.

Panic ensued and Spurs fans faced the prospect of a pain that Liverpool fans eventually had to suffer. Those at the front were bruised and battered well before kick-off and realised quickly they simply could not escape as things got worse. Some still speak of the crowd being packed so tight that their feet were off the ground as they moved.

Instead those in charge acted sensibly on the feedback of officers on the frontline. As a result they ordered the closure of the gates leading to the most crowded pens, and then directed incoming fans to safer areas. They acted somewhat late, but they did act. And many fans were helped out of the crowded spaces by fellow fans and police alike. They then sat along the edge of the pitch to watch the game unfold.

The injury tally was 38; the death toll, zero, because the right thing -- or, at least, the most right remaining thing -- was done. Tottenham did not have a disaster that day. They've had some epic failures on the pitch, and some big "offs" between their hooligan "firms" and those of opposing clubs; but, as far as I know, never a crowd disaster such as Hillsborough or the 1985 Bradford fire.

The game was a draw, and Spurs won the replay. The same result happened in the Final (without a crush, as it was at Wembley Stadium), as Spurs beat Manchester City. They also won the Cup the next season, although their Semi was at Villa Park, not Hillsborough.

*

In the 1983-84 season, Liverpool, a power in English football for the preceding 20 years, won the Football League, and also the European Cup -- the competitions now known as the Premier League and the UEFA Champions League, respectively. Winning either one would have qualified them for the 1984-85 European Cup.

But the 1984 Final was tainted. The Finals are set for neutral sites, much like American football's Super Bowls, but that year's final was set for the Stadio Olimpico in Rome -- and one of that stadium's teams, AS Roma, advanced to the Final.

Liverpool beat them, but not before their fans were attacked by Roma thugs, many of them doing not drive-by shootings, but drive-by slashings, riding those little Italian motor scooters past anyone who looked English, and reaching out with switchblade knives.

So when the 1985 European Cup Final turned out to be Liverpool against another Italian team, Turin-based Juventus, the Scouse fans were ready for it.

The game was played at Heysel Stadium in Brussels, the national stadium of Belgium, which was in bad shape and unfit to host such an important event. I've talked to Arsenal fans who were there for the 1980 European Cup Winners' Cup Final (where they lost to Spanish club Valencia), and they said it was in bad shape then.

Before the game, a group of Liverpool fans ran toward a group of Juve fans. Had the Juve fans stood their ground and fought, many of them might have gotten hurt, but it wouldn't have been as bad as what actually happened.

Instead, they ran, and many of them crashed into a wall, which collapsed. People and chunks of concrete fell onto people below, and 39 died. (Despite recommendations otherwise, the game was played anyway, and Juventus won.)

UEFA -- the Union of European Football Associations -- had previously banned individual English clubs from playing in their various competitions, at first indefinitely, and then limiting it. This had happened to Tottenham after the 1974 UEFA Cup Final in Rotterdam, the Netherlands against Rotterdam club Feyenoord. It had also happened to Leeds after the 1975 European Cup Final in Paris against Bayern Munich.

Both English clubs lost, and both had their bans lifted after 2 years. This time, instead of just sanctioning the team involved, UEFA banned all English clubs for 5 years, and tacked on an additional year for Liverpool.

What did the British government do about this insult? Led by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, they actually supported the decision. The Iron Lady (more like the Iron Bitch) hated sports, and particularly viewed football club supporters as undereducated, manners-lacking scum -- and likely to vote for her opponents in the Labour Party, rather than her own Conservative Party, anyway.

For this reason, football-mad areas such as Merseyside (home to Liverpool and Everton), Manchester, Birmingham (home to Birmingham City and Aston Villa), the North-East (home to Newcastle United, Sunderland and Middlesbrough), and the cities of Scotland and Wales still tend to vote Labour: Because of a backlash against Thatcher that has lasted nearly 35 years, and has not abated since her death.

By this point, even English liberals were angry at Liverpool, blaming them for their clubs not being able to compete in the European Cup (then a tournament for the defending champions of the various countries' national leagues), or the UEFA Cup (for other high-placing teams), or the European Cup Winners Cup (competed by the winners of the previous season's various national cups like the FA Cup).

Between the Heysel ban (which wasn't entirely Liverpool fans' fault) and Liverpool's perennial success (in 1986 they won the Double), pretty much anybody who wasn't already a Liverpool fan hated Liverpool's guts. (In other words, they were then what Manchester United would become.) Hold this thought.

*

Back to Hillsborough. In 1987, a Semifinal was played there, between Coventry City (which would go on to shock Spurs in the Final) and Leeds, whose fans were packed into the Leppings Lane End.

One of them described "disorganisation at the turnstiles and no steward or police direction inside the stadium, resulting in the crowd in one enclosure becoming so compressed he was at times unable to raise and clap his hands." Other accounts told of fans having to be pulled to safety from above.

In 1988, Hillsborough was again a Semifinal site, and the opposing teams were Liverpool, led by Kenny Dalglish (not yet retired as a player, but hardly ever putting himself into games); and Nottingham Forest, led by Brian Clough, once a great player whose career ended too soon due to injury, then became the enfant terrible of English managers. He led Derby County to the 1972 League title, and its East Midlands arch-rivals Forest to it in 1978, and to the European Cup in 1979 and '80. This fed into his massive ego, leading him to say, "I wouldn't say I'm the best manager in the country, but I'm in the top one."

Liverpool won the game, but would be stunned in the Final by South London club Wimbledon. But, for at least the 4th time, the Leppings Lane End was a problem. A Liverpool fan wrote to the FA before the next season's Semifinal, saying, "The whole area was packed solid to the point where it was impossible to move and where I, and others around me, felt considerable concern for personal safety."

The FA didn't listen, and, despite Hillsborough not having a valid safety certificate, it was chosen as a Semifinal site again in 1989. And, again, it would be Liverpool and Forest.

By the time of the Spurs fans' near-disaster of 1981, Hillsborough was one of several English stadiums whose caretakers -- more likely than not to be Conservative -- thought, "If they want to act like animals, we'll put them in a cage." And so perimeter fencing was put up, to make it harder for fans to storm the field -- what the English call a pitch invasion.

Spurs' White Hart Lane had this fencing at least as early as 1978 (as can be seen on the video of Arsenal's Christmas week 5-0 win over their rivals), because the Spurs hooligans were known at the time to be particularly nasty.

*

April 15, 1989. To paraphrase America's World War II President, Franklin D. Roosevelt: In Britain, this is a date which lives in infamy.

Construction on a major highway leading into Sheffield led to a lot of fans arriving late. As was nearly always the case in those days, English football matches kicked off precisely at 3:00 in the afternoon on Saturdays.

But as 3:00 approached, a lot of late-arriving fans weren't yet in the stadium. Many had tickets, but weren't able to get in. Many had tickets, but showed up at the wrong gate. Many didn't have tickets, but tried to get in anyway.

A police officer called the stadium operations office, saying that the kickoff should be delayed. This may have been the last moment on the day when the South Yorkshire Police did the right thing. The request was denied.

Remember: There was no Internet as we now know it, and certainly no social media, to warn people of problems: Not from civilians to the police, nor vice versa, nor within either group. Even mobile phones weren't common. There were beepers, but those were mainly for doctors -- and drug dealers. So the cops has to rely on their two-way radios, and civilians had nothing but word of mouth, notoriously short of full reliability.

Concerns were raised that people might be crushed to death outside the gate at the Leppings Lane End. So it was decided to open an additional gate. Unfortunately, the solution turned out to be far worse than the problem.

A BBC TV news report conjectured that if police had positioned two police horses correctly, they would have acted as breakwaters directing many fans into side pens. On this occasion, it was not done.

The fans rushing into the End had, at the time, no idea that they were causing a problem at the front of the End. People were being pushed into the perimeter fencing, and were literally crushed to death, asphyxiated. Some fans, desperate, began to climb the fencing, and got onto the pitch.

At 3:04, 4 minutes into the match, BBC announcer John Motson began to see this, and mentioned it on the air. A policeman ran onto the pitch, got the attention of referee Ray Lewis, and advised him to abandon the match -- call it off. At 3:06 PM, he did.

Emergency services were totally inadequate to the situation. There weren't enough stretchers. Some fans, seeing what was happening, tore advertising signs off the perimeter of the pitch, and used them as stretchers to get the dead and the badly injured out of the way.

But most of the policemen on hand didn't see missions of mercy. They saw fans running onto the pitch, and presumed it must be another hooligan invasion. They stopped people running to help others, and probably prevented the saving of several lives.

An official inquiry later said that everybody who died was already either dead, or beyond saving, by 3:15. Long-suppressed video evidence, backed up by time-stamps, later showed this not to be true in at least 1 case.

Liverpool goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar, who had fought in the all-white army of his native Rhodesia as a majority-black population won a civil war and made it into the nation of Zimbabwe, felt his soldier's training kick in, and ran to help -- but the police stopped him. They wouldn't let him be a hero, either.

Fans watching on television couldn't see the reason for the crush. All they saw was fans going onto the pitch, and many figured, "Same old Scousers, causing trouble again. Animals as usual."

But when it became clear that the game wouldn't be played, and why, an entire nation went into shock. This wasn't intentional violence that Liverpool fans were causing. This wasn't violence at all. This was a horrible accident, happening to them.

As I said, this was the pre-Internet age. But many fans at regular season League matches, having brought transistor radios, began to receive details. In his memoir Fever Pitch, writer and Arsenal fan Nick Hornby told of receiving the news at Highbury, watching Arsenal play Newcastle:

There were rumours emanating from those with radios, but we didn't really know anything about it until half-time, when there was no score given for the Liverpool-Forest semi-final, and even then nobody had any real idea of the sickening scale of it all...

A few people, those who had been to Hillsborough for the big occasions, were able to guess whereabouts in the ground the tragedy had occurred; but then, nobody who runs the game has ever been interested in the forebodings of fans.

By the time we got home it was clear that this wasn't just another football accident, the sort that happens once every few years, kills one or two unlucky people, and is general and casually regarded by all the relevant authorities as one of the hazards of our chosen diversion...

Though it is clear that the police messed up badly that afternoon, it would be terribly vengeful to accuse them of anything more than incompetence.

Whether Hornby knew it or not, this last point of his was already untrue before the match was abandoned.

Brian Marwood of Arsenal scored the only goal in that Arsenal-Newcastle match, but recalls that the crowd was somewhat subdued as the game moved toward the final whistle, because people were finding out that the death toll was going up, and up, and up.

In the film version of Fever Pitch, Colin Firth and Ruth Gemmell can be seen after the game, watching a televised news report, saying that at least 74 people have been reported dead. By the time the day was over, there were 94 confirmed deaths. Another died a few days later.

Another remained in a coma for 4 years before mercy finally took hold. This is why many sources written between 1989 and 1993, including Fever Pitch, list the death toll as 95, not the now-familiar 96. Nearly 700 others sustained injuries.

Of those who died, 79 were age 30 or younger. A pair of sisters, three pairs of brothers, and a father and son were among those who died, as were two men about to become fathers for the first time.

The oldest person to die at Hillsborough was 67-year-old Gerard Baron, brother of the late Liverpool player Kevin Baron. The youngest was only 10: His name was Jon-Paul Gilhooley, and he was a cousin of a boy about to turn 9, named Steven Gerrard. Gerrard went on to become one of the legends of English football -- Captain of Liverpool by 2003, meaning he was their Captain on the 15th, the 20th, and the 25th Anniversaries of the disaster.

By the 10th Anniversary in 1999, at least 3 people who survived were known to have committed suicide due to survivor's guilt, including 1 who couldn't go, and had sold his ticket to a man who died. Another had spent 8 years in psychiatric care.

It was a Saturday, and that night, on ABC World News Tonight, the story was shown. It wasn't the first awful soccer-crowd story to be shown on American TV news, so, like a lot of Americans, I just thought, "Well, there go those English soccer hooligans again, screwing things up for everybody."

I didn't get it. At all.

I was 19, not a little kid anymore. I should have known better.

You know who else should have known better? ABC. And NBC, and CBS, and CNN, and ESPN, and Time magazine, and its subsidiary Sports Illustrated, and other American media outlets. The story did not end that day. It went on and on.

But the American media figured, "It's not an American story, there were no Americans involved, so, now that we've reported it once, we should no longer care. Besides, it's not a sport Americans even care about. Let's move on."

I never heard another word about Hillsborough until 2008, when I plunged into soccer, finding, literally, a whole world of stories that I didn't know.

And I learned things about the Hillsborough Disaster that the American media either got wrong, or did say well enough, and then ignored.

Which still gives them higher moral ground than the English media, which behaved despicably in the aftermath.

*

First, some background. The Football Association Cup (the FA Cup) is one of the oldest continually-operating sports competitions in the world. Every soccer (football) club in England and Wales is eligible -- 736 of them entered the 2018-19 edition.

There are qualifying rounds before they get down to the "rounds proper":

* First Round, with 80 teams, on the 2nd weekend of November. Teams in the 3rd and 4th Divisions of English football (currently named League One and League Two) get a bye into this round.

* Second Round, with 40 teams, on the 1st weekend of December.

* Third Round, with 64 teams, on the 1st weekend of January (unless January 1 falls on a weekend, then it's pushed back a week). Teams in the 1st and 2nd Divisions (currently named the Premier League and The Championship) get a bye into this round.

* Fourth Round, with 32 teams, on the 4th weekend of January.

* Fifth Round, with 16 teams, on the 2nd weekend of February.

* Sixth Round, or Quarterfinals, on the 1st weekend of March.

* Semifinals, on the 2nd weekend of April.

* Final, on the 3rd Saturday in May.

Every round until the Quarterfinals is played at the stadium, or "ground," of one of the competing teams in the match. If it ends in a tie, or "draw," a replay is required, at the other team's ground.

The Semifinals, historically, have been played at neutral sites, usually in one of England's larger cities and in one of its larger stadiums. London's Highbury (Arsenal, North), White Hart Lane (Tottenham, also North) and Stamford Bridge (Chelsea, West) have hosted. So did both of the old Manchester stadiums, Old Trafford (Manchester United) and the now-demolished Maine Road (former home of Manchester City).

Villa Park in Birmingham (home of Aston Villa) was a frequent site, and so was Hillsborough Stadium, home of Sheffield Wednesday. That club was so named because the cricket club they were founded as played their matches on Wednesdays.

The Final, historically, has been played at England's national stadium, Wembley Stadium in London since 1923, opening for a Final, won by Bolton Wanderers of Lancashire over West Ham United of East London. After 2000, when the old Wembley was demolished to make way for the new one, it was held at the biggest remaining stadium in Britain, the Millennium Stadium in Cardiff, Wales. The new Wembley opened in 2007, and Chelsea of West London won the first Cup Final there. Since 2008, the Semifinals have also been held at Wembley, one on Saturday, the other on Sunday.

Owlerton Stadium opened in the Owlerton section of Sheffield in 1899 -- and The Wednesday became nicknamed the Owls because of the location. In 1914, it was renamed Hillsborough Stadium. By 1966, it had been mostly modernized, with a capacity of 34,000, was significantly lauded for this, and was selected as one of the venues for England's hosting of that year's World Cup.

A recent photo of Hillsborough Stadium.

The Leppings Lane End is at the bottom right.

It still looks rather antiquated.

But not all was as it seemed. The rise of hooliganism in the late 1960s led to crowd control measures that turned dangerous. And with the end sections of stadiums, behind the goals, nearly all being "terraces" -- stepped areas with railings but no seats, where fans would stand and watch the game -- fans would run in for good vantage points, leading to fans getting knocked over onto the field (or "pitch," as they'd say over there). With standees, Hillsborough could now hold over 55,000.

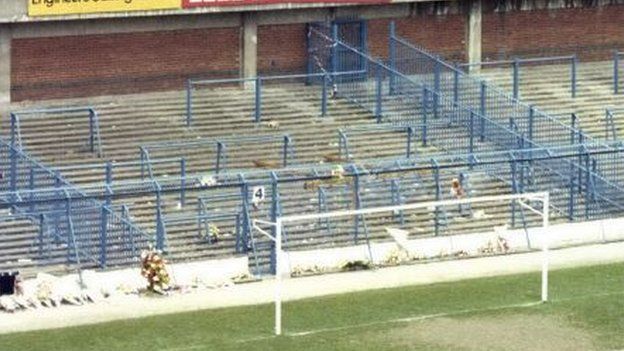

The Leppings Lane End, the day after the disaster.

This was typical for English soccer stadiums

of what Americans would call end zones: No seats.

In 1973, in miserable weather (even as far north as Yorkshire, it shouldn't have been snowing and sleeting on an April 17), Arsenal played North-East club Sunderland at Hillsborough. Arsenal fans were put into the West Stand, a.k.a. the Leppings Lane End. There was a rush into the End, and it spilled over onto the pitch. No major injuries, but it was a warning sign.

(Sunderland, then in the old Division Two, pulled off a shocker, beating 1971 League and Cup "Double" winners Arsenal, and then upsetting defending Cup holders Leeds United in the Final.)

In 1981, it got worse for Arsenal's North London arch-rivals, Tottenham Hotspur (a.k.a. Spurs). They reached the Semifinal, and were assigned to play Wolverhampton Wanderers (a.k.a. Wolves), at Hillsborough. The Spurs fans were also put into the Leppings Lane End, through the concourses that led to the various pens behind the goal. There was a crush, and as one Spurs fans' site (written by a man whose name I couldn't find) puts it:

People were crushed not because of surging support or bad behaviour, but simply because the spaces between the large metal fences were too small. Indeed there was a feeling even before then, without benefit of hindsight, that the supposed capacity of Leppings Lane was overstated and unsafe.

Panic ensued and Spurs fans faced the prospect of a pain that Liverpool fans eventually had to suffer. Those at the front were bruised and battered well before kick-off and realised quickly they simply could not escape as things got worse. Some still speak of the crowd being packed so tight that their feet were off the ground as they moved.

Instead those in charge acted sensibly on the feedback of officers on the frontline. As a result they ordered the closure of the gates leading to the most crowded pens, and then directed incoming fans to safer areas. They acted somewhat late, but they did act. And many fans were helped out of the crowded spaces by fellow fans and police alike. They then sat along the edge of the pitch to watch the game unfold.

The injury tally was 38; the death toll, zero, because the right thing -- or, at least, the most right remaining thing -- was done. Tottenham did not have a disaster that day. They've had some epic failures on the pitch, and some big "offs" between their hooligan "firms" and those of opposing clubs; but, as far as I know, never a crowd disaster such as Hillsborough or the 1985 Bradford fire.

The game was a draw, and Spurs won the replay. The same result happened in the Final (without a crush, as it was at Wembley Stadium), as Spurs beat Manchester City. They also won the Cup the next season, although their Semi was at Villa Park, not Hillsborough.

*

In the 1983-84 season, Liverpool, a power in English football for the preceding 20 years, won the Football League, and also the European Cup -- the competitions now known as the Premier League and the UEFA Champions League, respectively. Winning either one would have qualified them for the 1984-85 European Cup.

But the 1984 Final was tainted. The Finals are set for neutral sites, much like American football's Super Bowls, but that year's final was set for the Stadio Olimpico in Rome -- and one of that stadium's teams, AS Roma, advanced to the Final.

Liverpool beat them, but not before their fans were attacked by Roma thugs, many of them doing not drive-by shootings, but drive-by slashings, riding those little Italian motor scooters past anyone who looked English, and reaching out with switchblade knives.

So when the 1985 European Cup Final turned out to be Liverpool against another Italian team, Turin-based Juventus, the Scouse fans were ready for it.

The game was played at Heysel Stadium in Brussels, the national stadium of Belgium, which was in bad shape and unfit to host such an important event. I've talked to Arsenal fans who were there for the 1980 European Cup Winners' Cup Final (where they lost to Spanish club Valencia), and they said it was in bad shape then.

Before the game, a group of Liverpool fans ran toward a group of Juve fans. Had the Juve fans stood their ground and fought, many of them might have gotten hurt, but it wouldn't have been as bad as what actually happened.

Instead, they ran, and many of them crashed into a wall, which collapsed. People and chunks of concrete fell onto people below, and 39 died. (Despite recommendations otherwise, the game was played anyway, and Juventus won.)

UEFA -- the Union of European Football Associations -- had previously banned individual English clubs from playing in their various competitions, at first indefinitely, and then limiting it. This had happened to Tottenham after the 1974 UEFA Cup Final in Rotterdam, the Netherlands against Rotterdam club Feyenoord. It had also happened to Leeds after the 1975 European Cup Final in Paris against Bayern Munich.

Both English clubs lost, and both had their bans lifted after 2 years. This time, instead of just sanctioning the team involved, UEFA banned all English clubs for 5 years, and tacked on an additional year for Liverpool.

What did the British government do about this insult? Led by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, they actually supported the decision. The Iron Lady (more like the Iron Bitch) hated sports, and particularly viewed football club supporters as undereducated, manners-lacking scum -- and likely to vote for her opponents in the Labour Party, rather than her own Conservative Party, anyway.

For this reason, football-mad areas such as Merseyside (home to Liverpool and Everton), Manchester, Birmingham (home to Birmingham City and Aston Villa), the North-East (home to Newcastle United, Sunderland and Middlesbrough), and the cities of Scotland and Wales still tend to vote Labour: Because of a backlash against Thatcher that has lasted nearly 35 years, and has not abated since her death.

By this point, even English liberals were angry at Liverpool, blaming them for their clubs not being able to compete in the European Cup (then a tournament for the defending champions of the various countries' national leagues), or the UEFA Cup (for other high-placing teams), or the European Cup Winners Cup (competed by the winners of the previous season's various national cups like the FA Cup).

Between the Heysel ban (which wasn't entirely Liverpool fans' fault) and Liverpool's perennial success (in 1986 they won the Double), pretty much anybody who wasn't already a Liverpool fan hated Liverpool's guts. (In other words, they were then what Manchester United would become.) Hold this thought.

*

Back to Hillsborough. In 1987, a Semifinal was played there, between Coventry City (which would go on to shock Spurs in the Final) and Leeds, whose fans were packed into the Leppings Lane End.

One of them described "disorganisation at the turnstiles and no steward or police direction inside the stadium, resulting in the crowd in one enclosure becoming so compressed he was at times unable to raise and clap his hands." Other accounts told of fans having to be pulled to safety from above.

In 1988, Hillsborough was again a Semifinal site, and the opposing teams were Liverpool, led by Kenny Dalglish (not yet retired as a player, but hardly ever putting himself into games); and Nottingham Forest, led by Brian Clough, once a great player whose career ended too soon due to injury, then became the enfant terrible of English managers. He led Derby County to the 1972 League title, and its East Midlands arch-rivals Forest to it in 1978, and to the European Cup in 1979 and '80. This fed into his massive ego, leading him to say, "I wouldn't say I'm the best manager in the country, but I'm in the top one."

Liverpool won the game, but would be stunned in the Final by South London club Wimbledon. But, for at least the 4th time, the Leppings Lane End was a problem. A Liverpool fan wrote to the FA before the next season's Semifinal, saying, "The whole area was packed solid to the point where it was impossible to move and where I, and others around me, felt considerable concern for personal safety."

The FA didn't listen, and, despite Hillsborough not having a valid safety certificate, it was chosen as a Semifinal site again in 1989. And, again, it would be Liverpool and Forest.

By the time of the Spurs fans' near-disaster of 1981, Hillsborough was one of several English stadiums whose caretakers -- more likely than not to be Conservative -- thought, "If they want to act like animals, we'll put them in a cage." And so perimeter fencing was put up, to make it harder for fans to storm the field -- what the English call a pitch invasion.

Ewood Park, Blackburn, Lancashire, home of Blackburn Rovers.

This stadium has since been completely rebuilt.

Spurs' White Hart Lane had this fencing at least as early as 1978 (as can be seen on the video of Arsenal's Christmas week 5-0 win over their rivals), because the Spurs hooligans were known at the time to be particularly nasty.

*

April 15, 1989. To paraphrase America's World War II President, Franklin D. Roosevelt: In Britain, this is a date which lives in infamy.

Construction on a major highway leading into Sheffield led to a lot of fans arriving late. As was nearly always the case in those days, English football matches kicked off precisely at 3:00 in the afternoon on Saturdays.

But as 3:00 approached, a lot of late-arriving fans weren't yet in the stadium. Many had tickets, but weren't able to get in. Many had tickets, but showed up at the wrong gate. Many didn't have tickets, but tried to get in anyway.

A police officer called the stadium operations office, saying that the kickoff should be delayed. This may have been the last moment on the day when the South Yorkshire Police did the right thing. The request was denied.

Remember: There was no Internet as we now know it, and certainly no social media, to warn people of problems: Not from civilians to the police, nor vice versa, nor within either group. Even mobile phones weren't common. There were beepers, but those were mainly for doctors -- and drug dealers. So the cops has to rely on their two-way radios, and civilians had nothing but word of mouth, notoriously short of full reliability.

Concerns were raised that people might be crushed to death outside the gate at the Leppings Lane End. So it was decided to open an additional gate. Unfortunately, the solution turned out to be far worse than the problem.

A BBC TV news report conjectured that if police had positioned two police horses correctly, they would have acted as breakwaters directing many fans into side pens. On this occasion, it was not done.

The fans rushing into the End had, at the time, no idea that they were causing a problem at the front of the End. People were being pushed into the perimeter fencing, and were literally crushed to death, asphyxiated. Some fans, desperate, began to climb the fencing, and got onto the pitch.

At 3:04, 4 minutes into the match, BBC announcer John Motson began to see this, and mentioned it on the air. A policeman ran onto the pitch, got the attention of referee Ray Lewis, and advised him to abandon the match -- call it off. At 3:06 PM, he did.

Emergency services were totally inadequate to the situation. There weren't enough stretchers. Some fans, seeing what was happening, tore advertising signs off the perimeter of the pitch, and used them as stretchers to get the dead and the badly injured out of the way.

But most of the policemen on hand didn't see missions of mercy. They saw fans running onto the pitch, and presumed it must be another hooligan invasion. They stopped people running to help others, and probably prevented the saving of several lives.

An official inquiry later said that everybody who died was already either dead, or beyond saving, by 3:15. Long-suppressed video evidence, backed up by time-stamps, later showed this not to be true in at least 1 case.

Liverpool goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar, who had fought in the all-white army of his native Rhodesia as a majority-black population won a civil war and made it into the nation of Zimbabwe, felt his soldier's training kick in, and ran to help -- but the police stopped him. They wouldn't let him be a hero, either.

Fans watching on television couldn't see the reason for the crush. All they saw was fans going onto the pitch, and many figured, "Same old Scousers, causing trouble again. Animals as usual."

But when it became clear that the game wouldn't be played, and why, an entire nation went into shock. This wasn't intentional violence that Liverpool fans were causing. This wasn't violence at all. This was a horrible accident, happening to them.

As I said, this was the pre-Internet age. But many fans at regular season League matches, having brought transistor radios, began to receive details. In his memoir Fever Pitch, writer and Arsenal fan Nick Hornby told of receiving the news at Highbury, watching Arsenal play Newcastle:

There were rumours emanating from those with radios, but we didn't really know anything about it until half-time, when there was no score given for the Liverpool-Forest semi-final, and even then nobody had any real idea of the sickening scale of it all...

A few people, those who had been to Hillsborough for the big occasions, were able to guess whereabouts in the ground the tragedy had occurred; but then, nobody who runs the game has ever been interested in the forebodings of fans.

By the time we got home it was clear that this wasn't just another football accident, the sort that happens once every few years, kills one or two unlucky people, and is general and casually regarded by all the relevant authorities as one of the hazards of our chosen diversion...

Though it is clear that the police messed up badly that afternoon, it would be terribly vengeful to accuse them of anything more than incompetence.

Whether Hornby knew it or not, this last point of his was already untrue before the match was abandoned.

Brian Marwood of Arsenal scored the only goal in that Arsenal-Newcastle match, but recalls that the crowd was somewhat subdued as the game moved toward the final whistle, because people were finding out that the death toll was going up, and up, and up.

In the film version of Fever Pitch, Colin Firth and Ruth Gemmell can be seen after the game, watching a televised news report, saying that at least 74 people have been reported dead. By the time the day was over, there were 94 confirmed deaths. Another died a few days later.

Another remained in a coma for 4 years before mercy finally took hold. This is why many sources written between 1989 and 1993, including Fever Pitch, list the death toll as 95, not the now-familiar 96. Nearly 700 others sustained injuries.

Of those who died, 79 were age 30 or younger. A pair of sisters, three pairs of brothers, and a father and son were among those who died, as were two men about to become fathers for the first time.

The oldest person to die at Hillsborough was 67-year-old Gerard Baron, brother of the late Liverpool player Kevin Baron. The youngest was only 10: His name was Jon-Paul Gilhooley, and he was a cousin of a boy about to turn 9, named Steven Gerrard. Gerrard went on to become one of the legends of English football -- Captain of Liverpool by 2003, meaning he was their Captain on the 15th, the 20th, and the 25th Anniversaries of the disaster.

By the 10th Anniversary in 1999, at least 3 people who survived were known to have committed suicide due to survivor's guilt, including 1 who couldn't go, and had sold his ticket to a man who died. Another had spent 8 years in psychiatric care.

Many survivors fell victim to drinking and drugs. Marriages and families broke up due to the psychological strain of Hillsborough.

Liverpool manager Dalglish went to several of the Hillsborough victims' funerals, including 4 in one day. It had a profound effect on him, and was a factor in his deciding to resign as manager in 1991 (though he would return many years later).

Queen Elizabeth II, President George H.W. Bush, Pope John Paul II, and even the officials at Juventus, certainly bitter toward Liverpool for the preceding 4 years, sent official condolences.

And if that were the extent of it, the tragedy would be enough to still haunt Merseyside to this day.

*

But the British government made things worse for those who survived the disaster, and for those who lost loved ones in it. Police officials told bald-faced lies about what had happened, the higher-up covering for the mistakes of the lower-down. And the government accepted this.

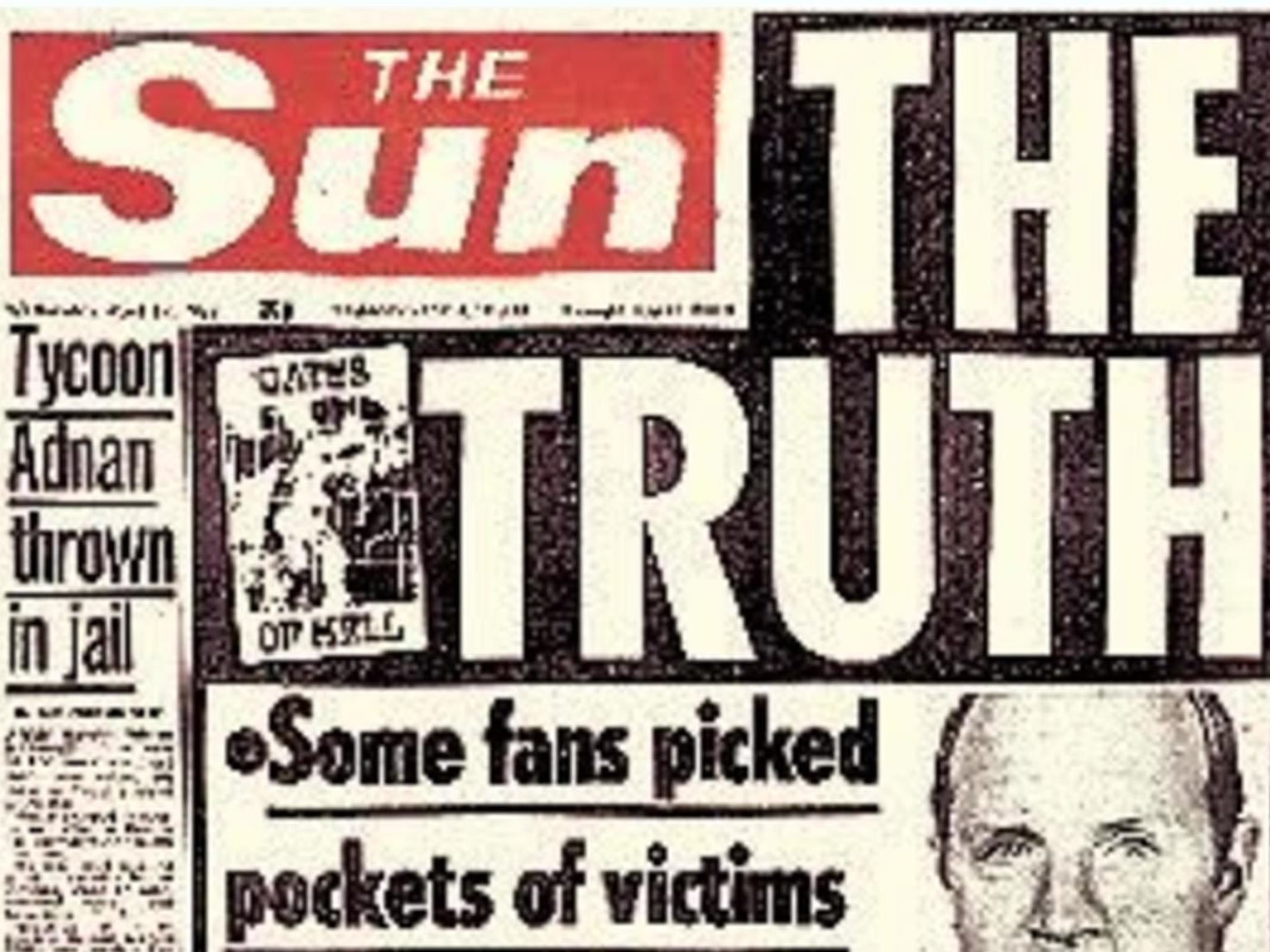

On April 19, just 4 days later, Rupert Murdoch's national newspaper The Sun, fitting his conservative bias and his faux populism, published a banner headline: "THE TRUTH":

* "Some fans picked pockets of victims" (Thus feeding the stereotype of Merseysiders being criminals, thieves in particular)

* "Some fans urinated on the brave cops" (Ditto, and keeping up the traditional Murdoch stance, in whatever country he publishes or broadcasts, of "The police are never wrong")

* "Some fans beat up PC giving kiss of life" (A Police Constable administering cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR)

All of these charges were lies, and Murdoch and his editors probably already knew this. Thatcher and her Cabinet probably knew it, too.

Sun editor Kelvin MacKenzie approved the headline, apologized for it in 1993, and retracted his apology in 2006: "I wasn't sorry then, and I'm not sorry now."

In 2017, MacKenzie, still working for The Sun, again published defamatory remarks about Liverpool as a city, and, in the same article, a racist comment about Everton player Ross Barkley. He was suspended by the paper, and Everton banned all people working for The Sun from their facilities, including their stadium, Goodison Park.

It wasn't just The Sun:

* The Daily Star: "Dead Fans Robbed By Drunk Thugs"

* The Sheffield Star: "Fans In Drunken Attacks On Police"

* The Liverpool Daily Post: "I Blame the Yobs" (another word for hooligans)

On September 12, 2012, 23 years later, the British government, through the Hillsborough Independent Panel, finally issued a report exonerating the Liverpool fans. This led MacKenzie to apologize once more, although we've seen what that is worth. Murdoch has never apologized for allowing the despicable front page to be printed, although he did have to print a response.

As the Spurs fan who was caught in the near-disaster at Hillsborough in 1981 put it:

English football still feels bitter about the sorrow of that day. And we all know why that is. The police screwed up; and with the help of the newspapers they blamed us. We football fans were accused of unspeakable horrors that I simply refuse to repeat. And plenty of normal human beings in this country believed it. Then when the truth became apparent the police who screwed up got off scot free for their criminal incompetence, largely thanks to the argument that it was an unprecedented situation.

But that argument was another lie.

As an Arsenal fan, I often accuse Tottenham fans of weak intelligence and poor taste. But this man was there, under circumstances all too close to what would later happen. He knew the score, and used his intelligence to be spot on.

The government and the media blamed the victims. This was cruel, and it was cowardly.

*

The Taylor Report, commissioned to find out what had caused the disaster, and to make recommendations as to what to do to prevent repeats, demanded the removal of perimeter fencing, and to make all English stadiums all-seater.

It took a few years, and led to many antiquated stadiums being either replaced by newer ones or completely renovated, but it was done. There has never been another disaster in an English stadium.

Hillsborough Stadium still stands, and is still the home of Sheffield Wednesday. After the Taylor Report, its conversion to all-seater reduced its capacity from about 55,000 to 39,732, and it hosted games in Euro 96, and an FA Cup Semifinal in 1997.

A proposal to expand it to 44,825 was accepted by the city council, but was put on hold after England did not get the rights to host the 2018 World Cup, which was the main reason for the proposed expansion.

*

In America, we cringe at the thought of April 15, as it is the deadline day for our federal taxes, and the anniversary of the death by assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

As sports fans, we celebrate April 15 as the anniversary of the Major League Baseball debut of Jackie Robinson, and the reintegration of the game. But it is also the anniversary of the bombs set off at the finish line of the Boston Marathon in 2013, killing 3 people.

Britain treats April 15 -- or "15 April," as they would write it -- with great solemnity, with moments of silence, with calls for "Justice for the 96" (often abbreviated to "JFT96"), and with the singing of a song which had already become an anthem of joy for Liverpool Football Club, but in 1989 became an anthem of sorrow, comfort, and recovery, the signature song from Rodgers & Hammerstein's 1945 Broadway musical Carousel: "You'll Never Walk Alone."

Liverpool manager Dalglish went to several of the Hillsborough victims' funerals, including 4 in one day. It had a profound effect on him, and was a factor in his deciding to resign as manager in 1991 (though he would return many years later).

Dalglish, conferring with the authorities at the game

And if that were the extent of it, the tragedy would be enough to still haunt Merseyside to this day.

*

But the British government made things worse for those who survived the disaster, and for those who lost loved ones in it. Police officials told bald-faced lies about what had happened, the higher-up covering for the mistakes of the lower-down. And the government accepted this.

On April 19, just 4 days later, Rupert Murdoch's national newspaper The Sun, fitting his conservative bias and his faux populism, published a banner headline: "THE TRUTH":

* "Some fans picked pockets of victims" (Thus feeding the stereotype of Merseysiders being criminals, thieves in particular)

* "Some fans urinated on the brave cops" (Ditto, and keeping up the traditional Murdoch stance, in whatever country he publishes or broadcasts, of "The police are never wrong")

* "Some fans beat up PC giving kiss of life" (A Police Constable administering cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR)

Lies.

All of these charges were lies, and Murdoch and his editors probably already knew this. Thatcher and her Cabinet probably knew it, too.

Sun editor Kelvin MacKenzie approved the headline, apologized for it in 1993, and retracted his apology in 2006: "I wasn't sorry then, and I'm not sorry now."

In 2017, MacKenzie, still working for The Sun, again published defamatory remarks about Liverpool as a city, and, in the same article, a racist comment about Everton player Ross Barkley. He was suspended by the paper, and Everton banned all people working for The Sun from their facilities, including their stadium, Goodison Park.

It wasn't just The Sun:

* The Daily Star: "Dead Fans Robbed By Drunk Thugs"

* The Sheffield Star: "Fans In Drunken Attacks On Police"

* The Liverpool Daily Post: "I Blame the Yobs" (another word for hooligans)

On September 12, 2012, 23 years later, the British government, through the Hillsborough Independent Panel, finally issued a report exonerating the Liverpool fans. This led MacKenzie to apologize once more, although we've seen what that is worth. Murdoch has never apologized for allowing the despicable front page to be printed, although he did have to print a response.

As the Spurs fan who was caught in the near-disaster at Hillsborough in 1981 put it:

English football still feels bitter about the sorrow of that day. And we all know why that is. The police screwed up; and with the help of the newspapers they blamed us. We football fans were accused of unspeakable horrors that I simply refuse to repeat. And plenty of normal human beings in this country believed it. Then when the truth became apparent the police who screwed up got off scot free for their criminal incompetence, largely thanks to the argument that it was an unprecedented situation.

But that argument was another lie.

As an Arsenal fan, I often accuse Tottenham fans of weak intelligence and poor taste. But this man was there, under circumstances all too close to what would later happen. He knew the score, and used his intelligence to be spot on.

The government and the media blamed the victims. This was cruel, and it was cowardly.

*

The aftermath: All English football matches were postponed for 2 weeks. On May 1, a "Bank Holiday Monday," every player across the country wore black armbands for matches, and a minute's silence was held before every kickoff.

The Semifinal was replayed on May 7, and Liverpool beat Nottingham Forest 3-1; and then, against neighboring Everton, won the FA Cup at Wembley on May 20, 3-2, on 2 extra time goals by Ian Rush.

The Liverpool-Arsenal match, scheduled for Liverpool's home of Anfield on April 22, was postponed to Friday night, May 26 -- and it turned out to be the League title-decider. When the Arsenal players came onto the pitch, they were holding bouquets of flowers, and each player in the starting XI ran toward the stands and gave his bouquet to a fan.

With the tiebreakers requiring Arsenal to win by 2 goals, at a stadium where they hadn't won at all in 15 years, to win the League title (and deny Liverpool the Double), they did just that, with Michael Thomas' goal in the 2nd minute of 2nd-half stoppage time giving Arsenal the most dramatic title in League history.

True, Liverpool fans did have the FA Cup, so they didn't exit the season empty-handed. But after all the death and destruction, and the lies and humiliation from the media and their own government, this defeat was another blow to their collective psyche.

The disaster happened 6 months before the Loma Prieta Earthquake interrupted the 1989 World Series in San Francisco. The much-maligned Candlestick Park held, protecting 60,000 people, although 63 people died around the San Francisco Bay Area.

There were stadium accidents in America early in the 20th Century, the worst being a balcony collapse at Baker Bowl in Philadelphia that killed 12 people in 1903. But nothing like Hillsborough has happened here since then.

The Semifinal was replayed on May 7, and Liverpool beat Nottingham Forest 3-1; and then, against neighboring Everton, won the FA Cup at Wembley on May 20, 3-2, on 2 extra time goals by Ian Rush.

The Liverpool-Arsenal match, scheduled for Liverpool's home of Anfield on April 22, was postponed to Friday night, May 26 -- and it turned out to be the League title-decider. When the Arsenal players came onto the pitch, they were holding bouquets of flowers, and each player in the starting XI ran toward the stands and gave his bouquet to a fan.

With the tiebreakers requiring Arsenal to win by 2 goals, at a stadium where they hadn't won at all in 15 years, to win the League title (and deny Liverpool the Double), they did just that, with Michael Thomas' goal in the 2nd minute of 2nd-half stoppage time giving Arsenal the most dramatic title in League history.

True, Liverpool fans did have the FA Cup, so they didn't exit the season empty-handed. But after all the death and destruction, and the lies and humiliation from the media and their own government, this defeat was another blow to their collective psyche.

The disaster happened 6 months before the Loma Prieta Earthquake interrupted the 1989 World Series in San Francisco. The much-maligned Candlestick Park held, protecting 60,000 people, although 63 people died around the San Francisco Bay Area.

There were stadium accidents in America early in the 20th Century, the worst being a balcony collapse at Baker Bowl in Philadelphia that killed 12 people in 1903. But nothing like Hillsborough has happened here since then.

The Taylor Report, commissioned to find out what had caused the disaster, and to make recommendations as to what to do to prevent repeats, demanded the removal of perimeter fencing, and to make all English stadiums all-seater.

It took a few years, and led to many antiquated stadiums being either replaced by newer ones or completely renovated, but it was done. There has never been another disaster in an English stadium.

Hillsborough Stadium still stands, and is still the home of Sheffield Wednesday. After the Taylor Report, its conversion to all-seater reduced its capacity from about 55,000 to 39,732, and it hosted games in Euro 96, and an FA Cup Semifinal in 1997.

A proposal to expand it to 44,825 was accepted by the city council, but was put on hold after England did not get the rights to host the 2018 World Cup, which was the main reason for the proposed expansion.

Hillsborough as it looks today, post-Taylor Report

In America, we cringe at the thought of April 15, as it is the deadline day for our federal taxes, and the anniversary of the death by assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

As sports fans, we celebrate April 15 as the anniversary of the Major League Baseball debut of Jackie Robinson, and the reintegration of the game. But it is also the anniversary of the bombs set off at the finish line of the Boston Marathon in 2013, killing 3 people.

Britain treats April 15 -- or "15 April," as they would write it -- with great solemnity, with moments of silence, with calls for "Justice for the 96" (often abbreviated to "JFT96"), and with the singing of a song which had already become an anthem of joy for Liverpool Football Club, but in 1989 became an anthem of sorrow, comfort, and recovery, the signature song from Rodgers & Hammerstein's 1945 Broadway musical Carousel: "You'll Never Walk Alone."

In 2014, to commemorate the 25th Anniversary of the disaster, every English match was postponed 7 minutes, with a minute's silence to begin at what would have been the 6-minute mark, in honor of the stoppage of play at 3:06. (10:06 AM, U.S. Eastern Time.) Liverpool marked the anniversary yesterday, before their game against Chelsea, which they won 2-0.

I've enlarged the picture, so that their names can be read.

There are documentaries about the disaster on YouTube. I recommend that you watch one. It is a story most Americans do not know. It is a story that anyone with a heart should know.

1 comment:

Very significant Information for us, I have think the representation of this Information is actually superb one. This is my first visit to your site. Tim hornibrook

Post a Comment