A pair of basketball legends died in the last few days -- although one is better known for playing baseball.

Donald Eugene Conley was born on November 10, 1930 in Muskogee, Oklahoma, where his mother was a full-blooded Cherokee. He inherited his height from her: She was 6 feet even, and he grew up, in Richland, Washington, to be 6-foot-8. At Richland High School, he was All-State in baseball and basketball, and State Champion in the high jump.

He went to nearby Washington State University, and in 1950 he was All-Conference in the Pacific Coast Conference (which evolved into today's Pac-12), and helped the Wazzu baseball team reach the College World Series. In August, he signed with the Boston Braves for a $3,000 bonus -- about $30,000 in today's money, so that was a nice chunk of change for a teenager. He was able to use that money to marry Kathryn Dizney (no relation to Walt Disney) in early 1951.

Conley's height made him ideal to both play basketball and to avoid serving in the Korean War: It was above the draft limit. And so, on April 17, 1952, wearing Number 56, he was able to make his major league debut. It didn't go so well: An Andy Pafko home run knocked him out of the box in the 3rd inning, and the Brooklyn Dodgers beat the Braves, 8-2 at Braves Field in Boston.

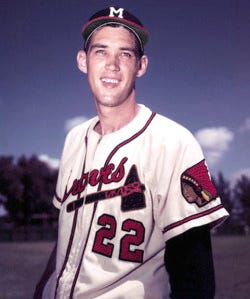

He struggled, going 0-3 with a 7.82 ERA in 4 games, and spent the rest of the 1952 season and all of 1953 in the minor leagues. By the time he returned, the Braves had moved to Milwaukee and, now wearing Number 22, he was ready. He went 14-9 in 1954, and in 1955 he went 11-7.

He made the All-Star Team both seasons, and was the last National League pitcher in the 1955 All-Star Game, at his home park, Milwaukee County Stadium. In the top of the 12th, he struck out the American League side: Al Kaline, Mickey Vernon and Al Rosen -- a Hall-of-Famer, and 2 guys who, perhaps, should be. In the bottom of the inning, Stan Musial hit a home run to give the National League the victory.

He struggled after that, though he did help the Braves win their 1st World Series in 1957. In 1958, they won the Pennant again, but he went 0-6, and was not included on the World Series roster. In 1959, he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies, and found his control again, to rebound somewhat. In 1961, he was traded again, to the Boston Red Sox -- because he was already playing basketball in the city.

So let me backtrack: In 1952, he was drafted by the Boston Celtics, and played for them in the 1952-53 season. The Braves, with teams then having all the power over the players, put it into his 1953 contract that he could not play another sport, forced him to stick with baseball.

But in 1958, having been traded to the Phillies, who had no objection to him also playing basketball, and with the Celtics still holding his NBA rights, he returned to the Boston Garden, winning NBA Championships as a reserve in 1959, 1960 and 1961. The Celtics would trade him to the Knicks, and give his Number 17 to John Havlicek, for whom it would be retired.

"He's the most incredible athlete in the country," said Celtics head coach and general manager Red Auerbach. "He's the only one who spends the entire year competing under the heaviest of pressure in 2 major sports. The average athlete would crack under that strain in a hurry. He thrives on it."

On July 26, 1962, Conley (wearing Number 18 for the Sox) brought about what was, by the standards of the time, one of the most bizarre incidents in baseball history. The Red Sox had just completed a series against the Yankees, losing 3 out of 4, including 13-3 in the finale, with Conley giving up 8 runs. The winning pitcher was rookie Jim Bouton, later the author of Ball Four. For all the weirdness that was to come, surprisingly, the notoriously iconoclastic Bouton was only involved in this most peripheral of ways.

After the game, the Sox got on the bus outside Yankee Stadium, and tried to get to the airport to fly to Washington to play the Senators. But they got stuck in traffic. Conley and teammate Elijah "Pumpsie" Green -- who, 3 years earlier, had become the 1st black player on the Red Sox, making them the last MLB team to racially integrate -- both had to go to the bathroom, and there was no toilet at the back of the bus.

They told the driver that, since they weren't moving anyway, he should let them off so they could use the bathroom at the bar they were in front of. He did. But when they came back out, the bus was gone.

That's dumb, but it's not bizarre. What's bizarre is what happened next. Conley and Green checked into the Waldorf-Astoria hotel, and went to the hotel's bar, and started drinking. They saw on the evening news that they were missing. Green decided he didn't want to be missing, and took a train down to Washington, and caught up with the Red Sox.

Conley decided he liked being missing. So, the next day, he went to Idlewild International Airport -- renamed John F. Kennedy International Airport in December 1963 -- and bought a ticket to fly to Israel. "I guess I thought they had weaker batters over there," he later said. But he had no passport, and was held up at the plane's gate. This caught the attention of a New York Post reporter, and Conley knew the game was up.

Can you imagine if this kind of incident had happened in the age of ESPN? In the age of Twitter? When he rejoined the team, owner Tom Yawkey fined him $1,500 -- about $12,000 in today's money. Yawkey told Conley that if there were no further incidents, he would give the money back at the end of the season. Both men kept their half of the deal.

Conley finished his baseball career with the 1963 Red Sox, ending 91-96, with a 3.82 ERA. He played the 1962-63 and 1963-64 seasons for the Knicks, and was still playing minor-league basketball as late as 1968.

"When I look back," he said in 2008, "I don't know how I did it. I really don't. I think I was having so much fun that it kept me going. I can't remember a teammate I didn't enjoy."

He added: "Basketball, to me, was easier to play, because it was an instinctive game. You can watch it, and you know instinctively what to do. Baseball is more of a thinking game."

He stayed in Massachusetts, settling in the Boston suburb of Foxborough, where the New England Patriots' stadiums would be built. He quit a heavy drinking habit while still playing -- during his meeting with Yawkey, also a major boozer, he was offered a drink and said, "I never touch the stuff" -- and became a Seventh-day Adventist.

He and his wife Kathryn ran an industrial paper supply business, so they were never short on cash. They would have 3 children, 7 grandchildren and 2 great-grandchildren. In 2004, Kathryn published One of a Kind, a biography of her husband, telling of how he played 2 sports at once, and how the family dealt with him being away for most of the year.

Gene Conley went to his final reward still the only man ever to win both the World Series and the NBA Championship. He died on July 4, 2017, in Foxborough, of heart trouble, at age 86.

With his death, there are now 11 surviving players from the 1957 World Champion Milwaukee Braves: Hank Aaron, Red Schoendienst, Del Crandall, Felix Mantilla, Bobby Malkmus, Mel Roach, Dick Cole, John DeMerit, Juan Pizarro, Taylor Phillips and Joey Jay.

There are now 6 surviving players from the 1959 World Champion Boston Celtics: Bill Russell, Bob Cousy, Frank Ramsey, Tom Heinsohn, and the unrelated Sam and K.C. Jones. Those same 6 survive from the 1960 World Champion Boston Celtics. And from the 1961 World Champion Boston Celtics, the 7 survivors are those 6 plus Tom "Satch" Sanders.

*

For 1 season, 1961-62, Gene Conley was a teammate of the other man I want to salute in this post.

Darrall Tucker Imhoff -- not "Darrell" or "Darryl" -- was born on October 11, 1938 in the Los Angeles suburb of San Gabriel, California. He grew up in nearby Alhambra, famous as the hometown of baseball legend Ralph Kiner -- and later infamous as the site of the murder that put legendary music producer Phil Spector in prison.

Imhoff, a 6-foot-10 center, was recruited to the University of California by head coach Pete Newell. As a junior in 1959, he led the team to the National Championship, and scored the winning basket against Jerry West's West Virginia team with 17 seconds left. The next year, he got them back into the Final, but lost to an Ohio State team with Jerry Lucas, the aforementioned John Havlicek, and a sixth man named Bobby Knight.

Newell then coached the U.S. team in the Olympics, a team that included Imhoff, West, Lucas, Oscar Robertson, Walt Bellamy, Bob Boozer. This may have been the best basketball team that had yet been assembled. It was so good that Havlicek only made it as an alternate, in case one of the players couldn't make the trip. They won the Gold Medal in Rome.

Known as "The Ax" -- with some irony, since Cal's arch-rivals, Stanford University, have an Axe as one of their main symbols, including the trophy given to the football game between the schools -- Imhoff was taken by the Knicks as the 3rd pick in the 1960 NBA Draft, adding him to a roster that included Richie Guerin and Willie Naulls. Things were looking up for Knick fans. But it didn't turn out so well. (Sound familiar?)

On March 2, 1962, the Knicks traveled to Hershey, Pennsylvania to play the Philadelphia Warriors, and Wilt Chamberlain scored 100 points in a single game. Aside from Wilt, the only players scoring at least 18 points were Knicks: Guerin 39, Cleveland Buckner 33, and Naulls 31. Imhoff could have gone down in history as the most-torched player in any NBA game, but he played only 20 minutes, and got just 7 points. (Wilt also had 25 rebounds.) The Warriors won, 169-147.

The Knicks traded Imhoff to the Detroit Pistons for future coaching star Gene Shue in the 1962 off-season, and the Pistons traded him to the Los Angeles Lakers in 1964. Now teamed with West and Elgin Baylor (already a pro in 1960 and thus ineligible for that Olympic team under the rules of the time), Imhoff found a groove, won the NBA Western Division in 1965, '66 and '68, and made the All-Star Team in 1967.

In 1968, the Philadelphia 76ers made one of the biggest management mistakes in a long history of them: With Imhoff outplayed by Bill Russell of the Celtics, the Lakers talked the Sixers into trading them Chamberlain for Imhoff. As legend put it, the Sixers traded the man who scored 100 points in a game for the man off whom he scored them. (This ignores the fact that Imhoff only played 20 of the 48 minutes.)

After that, Imhoff bounced around, playing for the 76ers, the Cincinnati Royals, and the Portland Trail Blazers. A torn ACL with Cincinnati in 1971 meant that he had to have surgery, and his career ended in 1973.

His last team was Portland, and he stayed in Oregon. He worked in sales and marketing for the United States Basketball Academy there, and broadcast for the Blazers, including during their 1977 NBA Championship season, getting him that ring that he was unable to get as a player.

He was elected to the Cal Athletic Hall of Fame and the Pac-10 (now Pac-12) Hall of Honor, and Cal retired his Number 40. He has not, however, been elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame in his own right -- though he was as a member of the 1960 U.S. Olympic team, which was collectively elected.

A testament to Imhoff's character is that he discovered that he was the only player ever coached by Pete Newell who had not gotten his college degree. He went back to school, got the credits he needed, and invited Newell to the graduation ceremony.

He was married, with 2 sons and 2 daughters. One daughter, Nancy Jones, is a high school basketball coach in Twin Falls, Idaho. Her son, Damon Jones, played baseball at Washington State (Conley's alma mater), and was just drafted by the Phillies (another of Conley's teams).

Darrall Imhoff died last Friday, June 30, 2017, of a heart attack, in Bend, Oregon. He was 78 years old.

With Imhoff's death, there are 3 surviving players from the 1959 National Champion California Golden Bears. Denny Fitzpatrick, Bill McClintock and Bob Dalton.

And there are now 7 surviving players from the 1960 Gold Medal-winning U.S. Olympic basketball team: West, Lucas, Robertson, Burdette "Burdie" Haldorson (the only holdover from the 1956 team that won the Gold Medal in Melbourne, Australia), Jay Arnette, Terry Dischinger, and Adrian "Odie" Smith.

UPDATE: Conley was buried at Highland Memory Gardens in Chapmanville, West Virginia. Imhoff's final resting place is not publicly known.

Friday, July 7, 2017

Gene Conley, 1930-2017; Darrall Imhoff, 1938-2017

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment