Right?

Well, there is some truth to that.

But it's like statistics. Statistics are like bikinis. What they reveal can be nice. What they don't reveal can be more important.

Top 10 Myths About the 1950s

1. America was at peace. This is a doozy. Remember Billy Joel's song "We Didn't Start the Fire"? He wrote it right after he turned 40 in May 1989, and also right after some kid came up to him and said, "Man, you were lucky, you grew up in the Fifties. Nothing happened in the Fifties."

Billy nearly flipped out. He asked the kid if he'd ever heard of the Korean War. The Red Scare. The Hungarian Freedom Fighters. When he got home, Billy started writing down those markers of his life, and found that he could neatly fit them in chronological order and (more or less) make them rhyme.

He was able to fit in Presidents Truman, Eisenhower and Nixon (although Nixon was only a Congressman when the decade began, then got elected to the Senate in November 1950, then Vice President on Ike's ticket in 1952, wasn't nominated for the top job until 1960, and didn't get it until 1968); Senator Joe McCarthy, McCarthy's legal counsel Roy Cohn, diplomat (and later Governor, Presidential candidate and Vice President) Nelson Rockefeller

He was also able to fit in Queen Elizabeth II; Red China, Mao Zedong's right-hand man Zhou En-Lai (but not Mao himself), both Koreas (North and South), South Korean dictator Syngman Rhee, and the Truce at Panmunjom that ended the war; Soviet leaders Josef Stalin, Georgi Malenkov and Nikita Khrushchev, the "Communist bloc" in general, the fall of Dienbienphu, the Rosenbergs, the hydrogen bomb whose secrets they leaked, the Hungarian Freedom Fighters of 1956, Dr. Zhivago author Boris Pasternak, Sputnik, Fidel Castro, and the U-2 spy-plane incident; Egyptian dictator Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Suez Canal Crisis he provoked, Argentine dictator Juan Peron, and the Lebanon situation of 1958 -- all before moving on to the 1960s and things like Belgians in the Congo.

When the decade began, Mao and Zhou had already taken over China, and on June 24, 1950, North Korea, backed by Stalin and Mao, invaded South Korea. The United Nations chose to fight, and President Harry S Truman sent in the troops. Oh yeah: Dwight D. Eisenhower, a.k.a. "Ike," wasn't President for the entire decade. He was President for 69.4 percent of it.

To be honest, Ike was a lot savvier than he let on to the people who thought he was square. But they were right: He was very, very square, by his own choice. Cool clock, though.

The Korean War lasted for over 3 years, until July 27, 1953. But even after that, America was involved -- whether the general public knew it or not -- in Iran, Guatemala, the 1956 Arab-Israeli war that resulted from the Suez Crisis, Lebanon, and, yes, from 1954 onward, Vietnam. (Oh, you were told JFK started that war? They lied to you.) But not, to the dismay of millions of Americans of Eastern European descent, Hungary.

All of this, while the general feeling of Cold War chilled us all. If that was "peace," then "war" must really have been hell.

Ironically, the best pop-culture expression of this feeling came after the end of the Cold War, when the TV show The West Wing addressed the "cold war" we've had with terrorism pretty much since the Munich Massacre at the 1972 Olympics. John Amos, playing Admiral Percy Fitzwallace, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff on the show, asks John Spencer, as White House of Chief of Staff Leo McGarry, if he can tell whether they're living in wartime or peacetime. McGarry, an Air Force pilot in Vietnam (at which point Fitz would have been a young Naval officer), says he can't tell.

And Fitz says, "I don't know who the world's leading expert on warfare is, but any list of the top has got to include me, and I can't tell when it's peacetime and wartime anymore."

Kids, that was what the Cold War was like at its chilliest. You never knew when it was going to go from zero to a thousand.

2. America had prosperity. For the most part, this is true. But there were actually 2 recessions that began in the decade. One lasted from July 1953 to May 1954, the other from August 1957 to April 1958. Another one under Eisenhower's leadership began in April 1960 and lasted until February 1961, making Ike the only President to preside over 3 separate recessions. These were relatively mild downturns compared to the ones from 1973 onward, but they did happen.

And that was for the nation as a whole. On the average in the 1950s, about 23 percent of Americans -- between 1 in 5, and 1 in 4 -- were living in poverty. For them, the "prosperity" of the Fifties was something that happened to others, something they could see, but not grasp; a cruel joke.

This was before the "War On Poverty." When I do "Top 10 Myths About the 1960s," I'll give details on how the War On Poverty did not, as the conservatives told us, fail. But, by 1973, the poverty rate had been cut in half, to about 12 percent.

3. Politically, it was a conservative era. Yes, Ike won landslide victories in 1952 and 1956. The one in 1952 also swept the Republican Party to control of both houses of Congress.

But the 1954 recession, and the excesses of McCarthy and his Red-baiting ilk, caused a backlash. In that year's Congressional elections, the Democrats gained 19 seats in the House and retook control, and they held that control for the next 40 years. The Dems gained just 2 seats in the Senate races, but that slim margin was enough to take control, and they held that control for the next 26 years. Despite the success that Nixon would have in 1968 and '72, it would be 1980 before Republicans were trusted again on a truly national scale.

In 1956, despite Ike's landslide win in his rematch with his 1952 opponent, former Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, the Democrats gained 2 House seats and broke even in the Senate.

In 1958, while the recession wasn't as bad as would later be seen in the 1970s, '80s, '90s and 2000s, there was another backlash. The Democrats, already in control of the House, gained 49 seats -- a total they haven't topped since. (They got 49 again in the "Watergate Babies" Class of '74, but that's the only time since '58 they've come close.) And they gained 15 seats in the Senate, a total neither party has approached since. Those '54 and '58 elections pretty much built the Democratic coalition that would pass John F. Kennedy's New Frontier and Lyndon Johnson's Great Society in the 1960s, and would dominate the Congress with their seniority in the '70s and '80s.

Ike himself was more conservative than Adlai, or the Speaker of the House, Sam Rayburn, or the Senate Majority Leader, Lyndon Johnson (the latter two from Texas). But, just as Bill Clinton would later be accused of not making a serious effort to end the Reagan era, Ike did little to dismantle Franklin Roosevelt's 1930s New Deal.

Indeed, the next favorite son of the conservatives, Barry Goldwater (first elected as Senator from Arizona in Ike's '52 landslide), called the Eisenhower Administration "a dime-store New Deal." "Mr. Sam" and LBJ were able to pass some liberal legislation and get Ike to sign it, although they could only get a watered-down Civil Rights Act in 1957, and they couldn't pass Medicare because Ike threatened a veto, scaring off some moderate Republicans who would otherwise have voted for it.

And did everybody like Ike? No, of course not. But he was very popular, right? After all, he won 2 landslides, winning States that Republicans, between 1932 and 1980, rarely won, right?

When he took office in January 1953, his approval rating was 68 percent. High, but understandable, considering he was a new President elected in a landslide. In November 1955, after his heart attack 2 months earlier, and again in December 1956, after his landslide re-election, Ike topped out at 78 percent.

But in September 1957, as that mild recession took hold and Southerners responded to his action in Little Rock, his rating began to go down. In February 1958, it went below 57 percent for the first time. In April, it was all the way down to 48 percent -- a minority. It got back above 60 percent in April 1959, but in July 1960, the week that JFK was nominated at his Convention, it was back down to 49. When Ike left office in January 1961, he was at 60 percent. Compare that to the other Presidents limited by the 22nd Amendment to 2 terms: In January 1989, Ronald Reagan was at 63 percent; in January 2001, Bill Clinton was at 66 percent; in January 2009, George W. Bush was at 34 percent.

So, yes, Ike was more popular than a lot of Presidents. But he had his moments where people didn't like him so much. And, while there was a Republican in the White House for the vast majority of the decade, the GOP was only in control of Congress for 20 percent of it, and it was a much more conservative era in terms of personal behavior than it was in terms of political activity.

4. The cars were cooler. When we think of Fifties cars, we might think of big bastard things with tailfins, like this 1959 Cadillac Coupe de Ville, one of the few things on Earth that can be pink (an oh-so-Fifties color) and still look badass:

Or maybe you think of spunky little sports cars, like the Chevrolet Corvette, which debuted in 1953. (This one is a 1958.)

In each case, no, I don't know if that's original paint.

Although tailfins were already being used in the 1940s, they didn't become especially popular until 1956 or so. Indeed, as with the Truman/Eisenhower shift in political power, car styles show that there was a significant divide between the early 1950s, which were really an extension of the 1940s, and the mid-to-late 1950s, the "cool" part of the decade.

This is a 1951 Chevy Fleetline. Had you been around then, you could have driven this vehicle to the Polo Grounds to see Bobby Thomson hit "The Shot Heard 'Round the World." Is this a "cool car"?

It's a nice design, but it's not a classic "Fifties" design. It definitely looks like a holdover from the Forties.

You also could have driven this little number to the Polo Grounds that day. This is a 1951 Hudson Hornet.

That doesn't look like the classic memory of a "Fifties car." Nor does this, a 1952 station wagon, familiar to anyone who's heard the 1958 song by the Playmates, "Beep Beep," as "the little Nash Rambler."

This was the 1950s equivalent of the minivan. No, it's not a Woodie. (Those were being phased out in the 1950s, at least in America.) Not even a rock and roll novelty song could hide the fact that this car was a piece of tin.

(Ferris Bueller's Day Off reference.)

Speaking of rock and roll...

5. Rock and roll. Yeah, from 1954 onward, and especially from the arrival of Elvis Presley on the national scene in early 1956, rock and roll took over.

Elvis singing "Hound Dog" on The Milton Berle Show,

June 3, 1956. Damn, would I like to know

what that outfit looked like in color.

Rock and roll ruled the radio, Daddy-O!

The hell it did. Once again, there's a major divide between the early Fifties and the late Fifties. When "Rock Around the Clock" by Bill Haley & His Comets topped the Top 100 chart in Billboard magazine's issue of July 9, 1955, it was a watershed moment. But that doesn't mean the styles of music popular up until that point went away.

Far from it. Teenagers may have voted with their dimes in the jukeboxes, but grownups still controlled radio stations and TV networks. This was still the time of Perry Como, Dean Martin, Nat King Cole, Tony Bennett, Pat Boone, Eddie Fisher, Guy Mitchell, mambo orchestras like that of Prez Prado, and, of course, it was the time of Frank Sinatra. Among women, the big singers were still Rosemary Clooney, Patti Page, Doris Day, Teresa Brewer, Kay Starr, the Andrews Sisters and the McGuire Sisters.

Some of those singers, the men and the women, had loads of quality. Some of them released some really good songs in the 1950s, even into the 1960s. But, let's face it, some of them put out weak records that stayed near the top of the charts for too long, proof that rock and roll had to happen.

And it wasn't just rock and roll. The 1950s were a golden age for jazz. Yes, Charlie Parker died. But Miles Davis made his best music, including albums with John Coltrane. By the time the decade ended, Coltrane had begun his own career as a headliner and an innovator. Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Gerry Mulligan and Dave Brubeck released groundbreaking works. Cannonball Adderley was big then -- and not just physically so.

L to R: Miles, Cannonball, 'Trane.

Recording the same song together.

This would be like if, today, Alicia Keys,

Lorde and Taylor Swift collaborated.

The Doors were heavily influenced by 1950s jazz: When keyboardist Ray Manzarek met drummer John Densmore, one of the first things Densmore said was, "Do you like Coltrane?" Manzarek said, "I love Coltrane! McCoy Tyner is my idol," and Densmore said, "I worship Elvin Jones, he is the greatest drummer on the planet. What about Miles?" And Manzarek, invoking Miles' pianist and arranger, said, "I'm Bill Evans!" (No, he wasn't, but he certainly learned from Evans.) The lyrics to "Light My Fire" were written by guitarist Robbie Krieger, and when he played it for the others, he recommended that they "put some long solos on it, like Coltrane did with 'My Favorite Things.'" They did, and the jazz influence seemed to suit singer Jim Morrison -- more about whom in a moment.

Speaking of "My Favorite Things," Coltrane warped it into something really smooth, but it began as a song from the musical The Sound of Music. Even into the early Sixties, Broadway "original cast albums" and film soundtracks nearly always topped the album charts (at least, when singles brought together in a "greatest hits" package weren't doing so). The idea that a non-soundtrack album could be a thing into and of itself didn't begin in rock and roll (Sinatra and his arrangers and producers were actually the major pioneers in this), but even rockers didn't really do this until acts like the Beatles, the Beach Boys and Bob Dylan began doing so in 1964, '65, '66.

Country music. Hank Williams died on New Year's Day 1953, but not before releasing classic stacks of wax. Johnny Cash arrived in mid-decade. So did George Jones. So did Patsy Cline.

The blues. The Fifties was the golden age of the blues. Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Willie Dixon and John Lee Hooker all recorded their best stuff then. And B.B. King launched his career.

And then there was folk music. Pete Seeger & the Weavers began the decade as superstars, but got blacklisted in the Red Scare. But along came Harry Belafonte, leading the calypso fad. And then, in 1958, the Kingston Trio hit the big time, paving the way for Dylan and Joan Baez and Glenn Yarborough and the New Christy Minstrels, and 1960s folk-rockers like Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, the Byrds, and the Lovin' Spoonful.

So, yes, the rock and roll revolution began in the mid-1950s. But it did not dominate. Elvis, even as early as May 1956, was being called "the king of rock and roll," but the kingdom wasn't especially large until those four longhaired knights arrived from Liverpool in 1964.

6. The Beat Generation. Before there were the punks of the 1970s, before there were the hippies of the 1960s, there was the Beat Generation of the 1950s -- the Beats, or "beatniks." "Beat Generation" + "Sputnik" = "Beatnik," implying that the Beats were Communists.

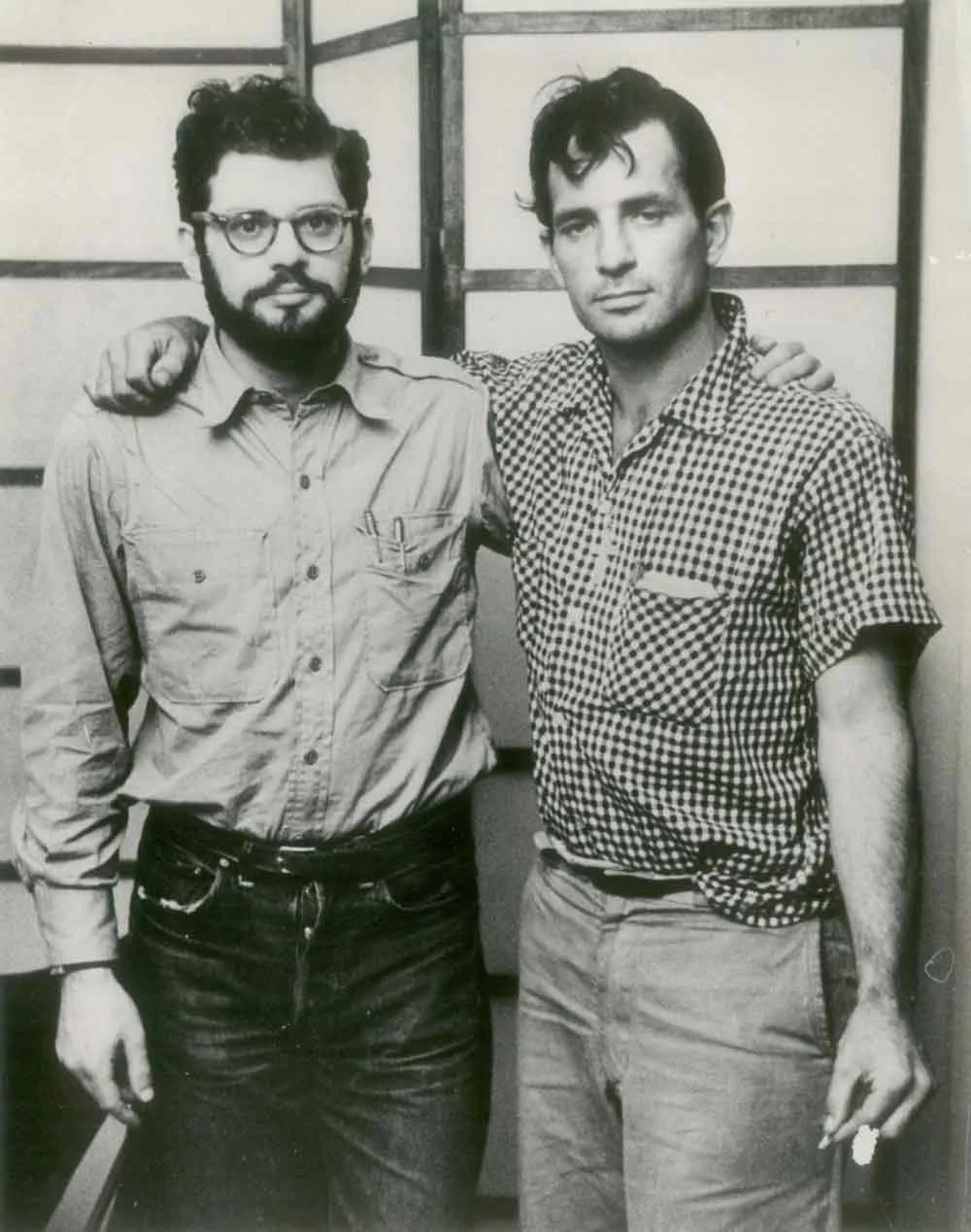

Poet Allen Ginsberg, poet-novelist Jack Kerouac, and novelist William S. Burroughs were the Big Three of the Beats. Here's Allen (on the left) and Jack.

The perception that the Beats hated bathing

was probably exaggerated, but

did neither of these men own a hairbrush?

Back to the Doors: Jim Morrison was a huge fan of the Beats (probably digging the fact that Kerouac was a prodigious drinker, and that they all loved their marijuana), and this greatly influenced his poetry. In the last few years of his life, Manzarek would often appear with Michael McClure, one of the few surviving Beats, and play organ behind McClure's reading. Jerry Garcia, leader of the Grateful Dead, was also a major influencee of the Beats -- which would explain why the Dead, like the Doors, turned what should have been 3-minute songs into who-knows-how-long-this-could-go-on.

So, yes, the Beats were very influential. And they were very popular in their time, right?

Wrong. As the term "beatnik" implies, they were, at best, widely mocked; at worst, hated, for their drug use, their apparent tendency toward beards, their leftward leanings, their drug use, their religious beliefs, and their sexual habits.

Most of the major writers didn't have beards, except Ginsberg by the late Fifties. Of the big names among the Beats, only Ginsberg was an out-and-out Communist. Drugs? Mainly marijuana, but Ginsberg would later advocate LSD, and Burroughs was hooked on heroin and wrote a memoir titled Junky. Religion? The Catholic Kerouac and the Jewish Ginsberg both embraced, and wrote about, Buddhism. Sex? Kerouac and his On the Road muse Neal Cassady were always writing about the women they slept with. Ginsberg was one of the few openly gay celebrities of the time, and Burroughs would screw anything that moved, male or female.

But an even bigger misperception of the Beats is that they were Fifties exemplars, cultural touchstones. Far from it. Ginsberg didn't publish Howl and Other Poems until 1956. Kerouac had published his 1st novel, The Town and the City, in 1950, but it was barely noticed at the time. (Mainly because it wasn't very good, by his own admission, and it isn't exactly typical of his later style. Even the name was different: He was listed on the cover as "John Kerouac." He was never called by the English name "John": He was the French "Jean" to his family, and the nickname "Jack" to his friends.) His magnum opus, On the Road, came out in September 1957, when the decade was 77 percent over.

Moreover, On the Road takes place between 1947 and 1950, the Truman and Joe DiMaggio years, not the Eisenhower and Mickey Mantle years. A generation later, the film Easy Rider would premiere, and the words on its poster could easily have been applied to Kerouac's time on the road: "A man went looking for America... and couldn't find it anywhere."

As an article on Cracked.com put it, Kerouac wasn't even writing about the same time period. It would be like the ravers of the late 1980s and early 1990s using a book about Studio 54 as their template for life -- or conservatives in 2014 looking back with fondness on George W. Bush's first term for the way to approach life, domestic politics and foreign policy.

And, like those hypothetical current conservatives and ravers, the Beatnik copycats of the late 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s missed the point of the Beats. They were essentially embracing a lifestyle that the Beats themselves had realized was pointless. Even their escapes provided only short-term respite from American life.

And while Ginsberg accepted the copycats, and the subsequent hippies, as kindred spirits, Kerouac sure didn't. As he got older, his innate Catholicism and conservatism kicked in, and he treated the copycats as poseurs. He lived long enough to see the rise of the hippies, and he was as repulsed by them as any Catholic (or Protestant) conservative. By the time he died due to the excesses of his drinking at the end of the 1960s, Kerouac was only 47, but he was in full "Get off my lawn, you filthy kids!" mode.

7. Pop culture in general. Look at the TV shows. I Love Lucy. Father Knows Best. The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Leave It to Beaver. These were happy families, typical of decent suburban America at the time. No sex scenes. No skimpy outfits. No violence. No filthy language. No angst. Just good, clean, wholesome entertainment. Where "those people" -- blacks, Hispanics, Jews, Muslims, gays -- were never seen, let alone heard. And where women knew their place: In the home.

I haven't seen enough of Father Knows Best to know what was really going on. I only know Robert Young as Marcus Welby, M.D. and as the man in the Sanka coffee commercials. But after the series went off the air, Lauren Chapin (Kitten) turned to drugs and prostitution, before getting clean through religion. And Billy Gray (Bud) pretty much exploded the myth by saying...

I wish there was some way I could tell the kids not to believe it. The dialogue, the situations, the characters they were all totally false. The show did everyone a disservice. The girls were always trained to use their feminine wiles, to pretend to be helpless to attract men. The show contributed to a lot of the problems between men and women that we see today...

I think we were all well motivated, but what we did was run a hoax. 'Father Knows Best' purported to be a reasonable facsimile of life. And the bad thing is, the model is so deceitful. It usually revolved around not wanting to tell the truth, either out of embarrassment, or not wanting to hurt someone.

All looking at "Father" with happy reverence.

I'm not questioning either the character

or the wisdom of either Jim Anderson or Robert Young.

But the show was hardly as realistic

as it would have you believe.

Ozzie and Harriet? Ozzie Nelson was pretty domineering in real life, though he did indulge his sons David and Eric (a.k.a. Ricky) with their love of rock and roll. But Rick (as he preferred to be called as an adult) had issues.

Someone once made the point that Leave It to Beaver debuted around the time of the Sputnik launch, and aired its last episode not long before the JFK assassination, and that, between those 2 upsetting events, it revealed a lot of youthful angst. Joan Jett once sang, "You don't lose when you lose fake friends." Wally Cleaver never figured out that Eddie Haskell was a fake friend. And little brother Theodore, a.k.a. the Beaver? Let's just say that he was damn lucky Ward and June were as good at parenting as they were, or else June would have had reason to be more than "worried about the Beaver."

No, it wasn't The Wonder Years, with the mean father and the asshole big brother (and the Beaver didn't have an attractive sister as Kevin Arnold did, either). But there were things going on in Beaver's head, troubles that you just didn't talk about back then -- to the point that we really still don't know what they were. I'm not insinuating that he was sniffing glue, or that he had been molested, or that he was being constantly bullied, or that he had witnessed something shocking like a murder or his father cheating on his mother. We just don't know. But if any of those things had been true, it would explain a lot.

Lucille Ball and her then-husband Desi Arnaz founded a production company (Desilu) together. Lucy was one of the few women to really have any power in Hollywood in the Fifties (or even in the Sixties, when the 2 of them kept Desilu together even after their divorce, before it was bought out by Paramount Pictures).

But look at the character of Lucy Ricardo: No, she wasn't dumb, but did she really think her schemes through? And what was her main ambition, anyway? To get into show business. "Ricky, can I be in the show?" "No, Loo-zee, you can't be in the show!" "Waaaaaaaah!" (Yes, she did cry a lot, but it was more whining than depression. Think Rachel on Friends.)

As for Desi's Ricky Ricardo, he was one of the few non-WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) stars on TV at the time. (Yes, the Italian Catholic Perry Como had a show, and so did the black Nat King Cole, but those were variety shows, not series where they played characters like themselves.) And even then, Desi was very much a white Cuban, not a black one like, say, later baseball pitcher Luis Tiant. But, in those years before Castro took over Cuba, boy, did Desi ever lay it on thick, and not just the accent. He was the public embodiment the very passionate Latino, clearly adoring his wife (though, in real life, cheating on her like crazy), but also flying into rages (as much as anyone, outside of Jackie Gleason, was allowed to do on TV in those days).

Did he object to the stereotype? Cleary not, as he and Lucy were co-executive producers: He couldn't complain to the boss, because he was the boss. As was Lucy. For Hispanics like Desi and women like Lucy, this was a step forward, but a step with a chain dragging them.

I mentioned Jackie Gleason. Now, I come to the elephant in the room.

(Yeah, that was a cheap shot.)

The Honeymooners. Gleason's Brooklyn bus driver, Ralph Kramden, was always yelling at his wife, Alice, played by Audrey Meadows. Today, we would call that "verbal abuse." And one of the things he yelled at her was threats. "You are gonna get yours." "You're going to the Moon!" "Hoo-hoo, would I like to... " "Oh-ho... Oh-ho... Bang! Zoom!"

And, just once in the "Classic 39" episodes -- he used this one a lot more when The Honeymooners was just a sketch on his earlier Jackie Gleason Show -- "One of these days, one of these days... POW! Right in the kisser!" As comedian Bill Maher put it, Ralph was always threatening to graduate from verbal to physical abuse, and mainstream America was fine with this and thought it was funny.

You know how many times Ralph actually hit Alice onscreen in those 39 episodes? Zero.

Because Alice wouldn't have put up with it. No, she couldn't have beaten the 6-foot, 300-pound Ralph in a genuine fight, but if she so much as slapped him just once, he would have been so shocked that the woman he loved had done that to him, that he would have backed down. For all his "king of the castle" bluster, Ralphie Boy was whipped.

Sure, Ralph would get in Alice's face and berate her, but she was just as likely to get into his. Check out this exchange, after she accused him of being cheap, leading to the lack of amenities in their apartment (and 328 Chauncey Street, which is a real address, was actually in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn, not in Bensonhurst like was so often said onscreen):

Ralph: When we got married, you said, "Ralph, I'd be happy to live in a tent with you!"

Alice: I'm still willing. I think it'd be an improvement.

Ralph, shaking his fist in her face: You wanna go to the Moon? Do ya wanna go to the Moon?

Alice: That would be an improvement, too!

Look at this picture. Ralph has his fist balled up. Is Alice intimidated? Hell no: She's standing her ground, ramrod straight, and giving Ralph a death stare.

She was from Brooklyn, too, you know: Alice Gibson Kramden was one tough redhead, a much tougher redhead than Lucille Esmeralda McGillicuddy Ricardo, who (as was said on her show) was from the real Lucy's hometown of Jamestown, in far western New York State. (Lucy wasn't a real redhead, either.) Alice gave as good as she got, and, while Ralph would frequently continue the verbal thrust-and-parry, just as often, he would back down, and make that big sad moon face, and be contrite, and apologize.

And she would forgive him. Because, deep down, she loved him as much as he loved her. And he would acknowledge just how good a fit she was for him, say, "Baby, you're the greatest!" and grab her and bend her over and kiss her like in romantic movies -- a much better "Pow, right in the kisser." For all his big talk, he was a romantic and a sentimentalist.

Lucille Ball may have been the first woman with any power in television production, but Audrey Meadows was TV's first feminist.

Also, Audrey wore some tight dresses on that show. How they got away with this in 1955 and '56, I don't know, but this was a few years before Annette Funicello's sweaters got interesting.

Westerns were very popular. Well, guess what, all you "Let's go back to the '50s and their values" types: On Gunsmoke, Marshal Matt Dillon (James Arness) demanded that everybody going into Dodge City's Longbranch Saloon surrender their firearms at the entrance. And not one desperado -- or even "law-abiding gun owner" -- told the 6-foot-6, 270-pound Marshal, "The only way yer gonna git mah gun is ta pry it from mah cold, dead hands!"

"If you insist."

Then there was Dragnet, the defining police drama of television's first generation. Show creator, executive producer and star Jack Webb (as Sergeant Joe Friday) insisted that the police be shown firing their weapons a maximum of one time per episode. The point was not to show how violence crime, and the fighting of it, could be; but to solve the crime, to show the detective work that went into it, to show that it wasn't all bang-bang, to punish the guilty, and to protect the innocent. (This is also the purpose of Batman: To be a detective, and to solve the crime. Kicking ass is secondary.)

And while the 1950s were a time when cop shows would show women as victims or witnesses, rarely would they be the criminals. But even female criminals would be seen more often than women in the precinct house: No lady cops, not in uniform, nor (God forbid, at least until the 1970s) as detectives. Maybe as secretaries or dispatchers. And none of those aforementioned female criminals would be hookers.

And let's not forget all those science-fiction movies, many of them featuring invaders from other planets, like the 1953 version of H.G. Wells' The War of the Worlds. Or the monster movies, featuring Godzilla and the Creature from the Black Lagoon and the giant ants from Them! All allegories for the Cold War.

By the way: In addition to Jackie Gleason only using "One of these days... " once in the "Classic 39," Desi Arnaz never, not once, said, "Lucy, you got some 'splaining to do!" And Jack Webb never said, "Just the facts, ma'am." Variations on that, yes; the exact words, no. In each case, it was parodies that put those words in our minds, just as it did for the words never spoken on Star Trek: "Beam me up, Scotty."

8. The Brooklyn Dodgers & the New York Giants. As we all know, the Dodgers and Giants were beloved in New York, right up until 1957, when, after the season, the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, and the Giants moved to San Francisco. And this traumatized New York, especially Brooklyn, which never recovered. What followed, at least until Mayor Rudy Giuliani began to clean up the City in the 1990s, was nearly 40 years of degradation, crime and filth.

Let's put the latter part to rest right now. Brooklyn was always poor, home to the newest immigrant groups. The Irish, then the Jews, then the Italians, then the black Southerners, then the Hispanics, then the black Caribbeans, and now the black Africans and the Arabs. Along with each of the preceding, who have never completely gone away, leaving behind remnants of their communities even after most of them moved up the economic ladder and moved east to Queens or Long Island, north to Westchester or Connecticut, or west to Staten Island or New Jersey.

But Brooklyn had slums long before 1957. And the thing that really ruined things there was the loss of industry, the manufacturing base. Emblematic of this was the closing of the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1966. While there was already decline in the Borough, the closing of the Navy Yard was the real "nail in the coffin" for "the old Brooklyn" -- not the loss of the Dodgers.

Duke Snider and Willie Mays

But just how popular were the Dodgers and the Giants? From the first postwar season of 1946, to the last season in Brooklyn in 1957, the Dodgers averaged just 16,800 fans per home game, in a ballpark, Ebbets Field, that seated 31,497. That's just 53 percent of capacity.

They peaked at 23,323 in 1947, the first year that Jackie Robinson played for them. An influx of black fans? Possibly, but it wasn't appreciably higher than the year before, 22,889. More like it was the postwar hunger for baseball still taking effect. Surely, there were more black fans; but, by and large, black fans couldn't afford to go to games as often as white fans could.

In 1949, the Dodgers averaged 20,945 fans -- and never topped 17,000 as a seasonal per-game average again until 1958, their first year in Los Angeles (the novelty factor taking hold there). That overall 1947 total was 1,807,526, and while they got at least 1 million total fans every year after World War II, in 1954, '55 (the World Championship season) and '57, they just got past the million mark. In contrast, in the 56 seasons that the Dodgers have played in Los Angeles, only 5 times, and not at all since 1970, have they failed to top that 1947 Brooklyn peak.

The Giants did even worse: Their per-game average at the 55,987-seat Polo Grounds from 1946 to 1957 was 13,642 -- just 24 percent of capacity. In other words, the average Dodger crowd and the average Giant crowd combined, 30,442, would not have sold out Ebbets Field, let alone the Polo Grounds. Double it, and it wouldn't have filled the pre-renovation original Yankee Stadium.

And how do these figures compare to the team then frequently described as "the lordly Yankees"? They averaged 24,063 from 1946 to 1957 -- over 10,000 more than the Giants and 7,000 more than the Dodgers, but still not great.

Was it all about winning? Not really: In that 12-year stretch, the Giants won a couple of Pennants and only got close a couple of other times; but the Dodgers were at least in the Pennant race every year, were still alive in at least the 154th and last scheduled game of the season 9 out of 12 times, and won 6 Pennants. And yet the Dodgers got the kind of attendance that's a couple of thousand less than we mock the contending Tampa Bay Rays for getting. (Well, you have to remember: Like the 1950s Dodgers, the Rays' average fan was born in the 1930s.)

Some context is needed: Most teams weren't doing well at the box office in the Fifties. That's why the Braves left Boston to the Red Sox and moved to Milwaukee for 1953, and got more fans in their first homestand in Wisconsin than they did in their last season in Massachusetts. That's why the Browns left St. Louis to the Cardinals and moved to Baltimore for 1954, and got nearly as many fans in their first season as the Orioles as they did in their last three seasons as the Browns. That's why the Athletics left Philadelphia to the Phillies and moved to Kansas City for 1955, and got more fans in their first season in the Midwest than they got in their last three seasons in the Northeast. And that's why the Senators left Washington and moved to Minnesota for 1961, and got more fans in their first season as the Twins than they got in their last two seasons in D.C.

The great American middle class was growing, but it hadn't yet reached the point where a Major League Baseball team could get 2 million fans in a season. Even the Yankees didn't cross the 2 million mark between 1951 and 1975, despite 12 Pennants over that stretch.

So, while the Dodgers were more popular than any team except the Yankees, it was the 1950s nostalgia wave that began in the 1970s, including Roger Kahn's 1971 book about them, The Boys of Summer, that propped the Dodgers up as an ideal, even fetishized them, at a time when baseball, along with so many other things (Vietnam, race riots, Watergate, gas prices, terrorism) seemed to be screwed up.

9. Everybody knew their place. If true, then this was a bad thing, because people were being denied a proper place because of race, religion, gender, or sexual orientation.

But it's not true. Lots of people refused to accept their place. Rosa Parks refused -- and there were bus boycotts before the one she began in Montgomery, Alabama. Oliver L. Brown and the other parents who were the plaintiffs in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas refused, and public schools in America were desegregated. The Little Rock Nine refused, and Eisenhower, while no progressive on race, chose to uphold the federal law and sent the U.S. Army's famed 101st Airborne Division to enforce it.

True, there wasn't much of a women's movement. Or one for the rights of Hispanics, or non-Christians. Those would come in the 1960s. For Asians, Native Americans, gays and the handicapped, the 1970s would see the flowerings of their efforts.

UPDATE: I quoted Bill Maher earlier. In 2016, on his show Real Time, he did a routine about "'50s Guys," and closed by saying, "The Fifties weren't that great if you were black, or gay, or a woman, which is why Little Richard was always screaming."

10. It was a simpler time. I think the first 9 have pretty much vaporized this one. The truth is, when people reach middle age, and look at the world around them, and say, "There's got to be something better than this," they tend to look back on their childhood, when angst was, as Terry Jacks sang in 1974, when you "learned of love and ABC's, skinned our hearts and skinned our knees."

We've seen it before: Today's Tea Partiers came of age in the Reagan Eighties; Democrats then, in the Kennedy-then-hippie Sixties; people of either political leaning in the Seventies, "the Fabulous Fifties"; conservatives hating the hippies, the oh-so-certain Forties; Fifties parents looking at their kids turning into James Dean, the Roaring Twenties (as if they weren't getting drunk on bathtub gin); their parents, the simpler age of William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt at the turn of the 20th Century.

The Fifties? It was a time when our government didn't lie us into war (except it did), when Presidents didn't get shot (but private citizens got lynched), when TV was clean (except when Ralph threatened to send Alice to the Moon), when cars were cool (except when you realized they got 5 miles to the gallon), and when rock and roll was fun and didn't have lyrics about sex and drugs (except there were plenty of lyrics that were about sex, if you paid attention to them).

It was a simpler time, if you were a kid then. Not if you were a parent then, or anyone willing to look up the truth now.

The 1950s were not a time when "nothing happened." I think even people who believe all or most of the myths listed here would agree with that.

But a lot of what you think was happening wasn't -- or, it wasn't happening the way you've been told it did.

We've seen it before: Today's Tea Partiers came of age in the Reagan Eighties; Democrats then, in the Kennedy-then-hippie Sixties; people of either political leaning in the Seventies, "the Fabulous Fifties"; conservatives hating the hippies, the oh-so-certain Forties; Fifties parents looking at their kids turning into James Dean, the Roaring Twenties (as if they weren't getting drunk on bathtub gin); their parents, the simpler age of William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt at the turn of the 20th Century.

The Fifties? It was a time when our government didn't lie us into war (except it did), when Presidents didn't get shot (but private citizens got lynched), when TV was clean (except when Ralph threatened to send Alice to the Moon), when cars were cool (except when you realized they got 5 miles to the gallon), and when rock and roll was fun and didn't have lyrics about sex and drugs (except there were plenty of lyrics that were about sex, if you paid attention to them).

It was a simpler time, if you were a kid then. Not if you were a parent then, or anyone willing to look up the truth now.

The 1950s were not a time when "nothing happened." I think even people who believe all or most of the myths listed here would agree with that.

But a lot of what you think was happening wasn't -- or, it wasn't happening the way you've been told it did.

3 comments:

As someone who loves studying about the 1950's but hates "nostalgia," I loved your blog!

You hit it right on the head about why people looking back on any time period say "it was simpler." It was "simpler" in their minds because the just kids at the time.

I realize that it's "Top 10 Myths", so this number 11 wouldn't make the list, but I would like to add that in recent years, another myth has popped up (and I've seen it in "nostalgia" Facebook groups and even in a rock n' roll blog: Juvenile delinquency in the 1950's meant gum chewing and spitting on sidewalks. There were no killings.

Statements like that ignore incidents such as the various gang killings that grabbed New York and San Francisco headlines. (I'm guessing you are familiar with the story of 15 year old Michael Farmer, the polio victim who was killed by gang members in a New York park in 1957. I'm also guessing that proponents of the "harmless and safe" 1950's have not or have chosen to ignore that incident, which was really just one of many.)

As a '50's fan I will definitely be sharing your blog!

Thank you. Actually, I didn't know about the Michael Farmer story. But, given my own issues with my legs and how my jackass classmates reacted to that in the suburbs in the late 1970s, I can't say I'm surprised.

I knew about Charlie Starkweather, but that was because of songs by Bruce Springsteen and Billy Joel. I knew that Beat writer Jack Kerouac got his head bashed into the sidewalk outside the Kettle of Fish on Macdougal Street in 1959, so, as John Lennon later found out, fame was no protection. (The Kettle of Fish was a rough bar at the time. There's a far tamer place by the name now, a few blocks away on Christopher Street. It's known as a hangout for Green Bay Packer fans.)

Post a Comment