Let the record show that Tommy Lasorda was one of the best ambassadors the game of baseball has ever known.

Let the record also show that Tommy Lasorda was not a good person.

Thomas Charles Lasorda was born on September 22, 1927 in Norristown, Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia. He graduated from Norristown High School, as would another sports Hall-of-Famer, Washington Redskin running back Bobby Mitchell.

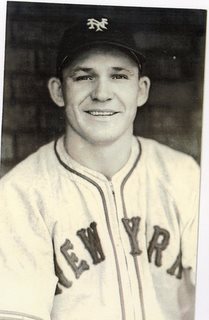

While at Norristown High, in 1943, Tommy went to his 1st live game in what would later be called Major League Baseball. It was at Shibe Park, where the Philadelphia Phillies were playing the New York Giants. When the game ended, Tommy waited outside the runway between the dugout and the clubhouse, hoping to get some autographs. The first player he asked to sign his scorecard not only refused, but shoved him.

"I couldn't believe it," he said. "Here was the first big-league player I'd ever seen up close, the first one I ever dared speak to, and what he did was shove me up against the wall." He got a look at the player's uniform number. It was 6. He looked on the scorecard. Number 6 was outfielder James Walter "Buster" Maynard. Tommy Lasorda decided he would never forget the name.

In 1945, Lasorda was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers as a pitcher. Despite World War II having ended, the military draft had not, and he spent the 1946 and 1947 seasons in the U.S. Army. On May 31, 1948, pitching for the Schenectady Blue Jays against the Amsterdam Rugmakers, he pitched 15 innings and struck out 25 batters, a professional record that would stand only 4 years. But he also got a hit to drive in the winning run.

In 1949, he had been called up to the Greenville Spinners, of Greenville, South Carolina, in the Class A South Atlantic League. He was on the way up. He started against the Augusta Tigers of Augusta, Georgia. The public address announcer introduced a batter: Buster Maynard.

Now 36, and having last played in the majors 3 years earlier, Maynard was instantly recognized by Lasorda, who was determined to give him a reminder of the old saying: "Be kind to the people you meet on the way up, because you're going to meet the same people on the way down." Tommy threw 3 brushback pitches. None hit Maynard, but after the 3rd, Maynard charged the mound, and the men had to be separated.

After the game Maynard came into the Spinner locker room. He didn't recognize Tommy, and asked, "Listen, kid, did I ever meet you before?"

Lasorda: "Not exactly."

Maynard: "Did I bat against you someplace, maybe?"

Lasorda: "Nope."

Maynard: "Well, why were you tryin' to take my head off out there?"

Lasorda: "Because you didn't give me an autograph at Shibe Park in 1943."

Tommy would tell his players this story, saying, "Always give an autograph when somebody asks you. You never know who you're going to meet someday."

There have always been what are now called "Quadruple-A" players: Players too good for Triple-A ball, but not really good enough to stay in the major leagues. Tommy Lasorda was one of them. In spite of a continually changing staff in Brooklyn, complicated by Don Newcombe missing the 1952 and '53 seasons by serving in the Korean War, Lasorda was stuck at the Dodgers' top farm team, the Montreal Royals. Dividing his time between starting and relief, he went 9-4 in 1950 and 12-8 in 1951, helping them win the 1951 International League Pennant. Mainly starting thereafter, he went 14-5 in 1952, 17-8 in 1953 to help win another Pennant, and 14-5 again in 1954, before being called up.

He made his debut on August 5, at Ebbets Field. The Dodgers lost to the St. Louis Cardinals, 13-4. Wearing Number 29, he pitched the 6th, 7th and 8th innings, allowing 3 runs on 6 hits, walking 1 and striking out 1. He appeared in 4 games for the Dodgers in 1954, all in relief.

Switching to Number 27, he appeared in 4 more games in 1955, starting 1, on May 5. He tied a major league record with 3 wild pitches in the 1st inning, and got spiked and injured by the Cardinals' Wally Moon when he tried to cover the plate. He had no decisions, and, that wild 1st inning aside, was wholly unremarkable.

He made his last appearance in a Brooklyn uniform on June 6, 1955. Shortly thereafter, Dodger general manager Emil "Buzzie" Bavasi called him in, and told him that he was being sent back down to Montreal. He objected. Bavasi decided to give him a chance to defend himself, and asked who he would have sent down in his place.

Lasorda made a nomination, another lefthander, one who hadn't yet made a major league appearance. Bavasi told him that that lefty couldn't be sent down: He had been given a big signing, and thus qualified under MLB's "bonus baby" rule: He had to be kept on the major league roster for at least 2 seasons, even if he never appeared in a game. In other words, he couldn't be sent down in 1955 or 1956. The rule was designed to keep teams from making mistakes on young pitchers who weren't ready.

Lasorda insisted he was a better pitcher than this other lefty. Bavasi's hands were tied: He had to keep that lefty in Brooklyn. And so, Lasorda would never again play for the Dodgers.

That other lefty was Sandy Koufax. To the end, Lasorda insisted that, at the time, he was a better pitcher than Koufax. Even before he learned how to control his pitches, Koufax was a better pitcher than Lasorda.

On March 2, 1956, the Kansas City Athletics decided to take Lasorda off the Dodgers' hands, purchasing him for a sum that has never been publicly disclosed. He made 18 appearances for the A's, including 5 starts. He went 0-4, with an ERA of 6.15.

His most notable appearance in a K.C. uniform -- Number 23 -- came on May 22, at Kansas City Municipal Stadium. Pitchers for the A's and the Yankees took turns brushing players back. Late in the game, Lasorda knocked Hank Bauer down. From the dugout, Billy Martin yelled, "Knock him down, and we'll chase you out of the park and into the river!"

Tommy was a Philly guy. He wasn't going to be intimidated by a New York player. He walked toward the Yankee dugout. Billy, as was so often the case, was ready to start a fight, but his teammates held him back.

On July 8, he appeared for the A's. On July 11, the A's traded him -- to, of all teams, the Yankees, for Wally Burnette, a pitcher who had yet to make his debut. He would make 68 appearances in the majors, all for the A's over the next 2 1/2 seasons, and if he's remembered for anything, it's for being traded for Tommy Lasorda.

Who never appeared in the majors again. The Yankees sent him down to their top farm team, the Denver Bears. (Whether they were trying to prevent another incident between him and Martin, or any of the other players, is unknown.) There, he played for Ralph Houk, who would later manage the Yankees to 3 Pennants, and would also manage the Detroit Tigers and the Boston Red Sox.

"Ralph taught me that if you treat players like human beings, they will play like Superman," he told Los Angeles Times columnist Bill Plaschke, in the biography I Live for This: Baseball's Last True Believer. "He taught me how a pat on a shoulder can be just as important as a kick in the butt."

Houk would lead the Bears to the American Association Pennant in 1957, but Lasorda wouldn't play much of a part in it. On May 26, the Dodgers bought him back, and assigned him to a farm team they had just bought: The Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. Dodger owner Walter O'Malley had bought the Angels from their previous parent club, the Chicago Cubs, thus buying the rights to the Los Angeles market in the National League. (In return, he gave the Cubs the Fort Worth Panthers of the Texas League, and $3 million.)

Tommy went 7-10 for the Angels. When the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles for 1958, they moved the Angels as well, to the Pacific Northwest, becoming the Spokane Indians. Instead of keeping Tommy in L.A. for the big club, or keeping him with the franchise and send him to Eastern Washington State, they sent him back to the Montreal Royals.

He went 18-6 in 1958. Despite this, and the Dodgers' 7th-place finish as their "Boys of Summer" had gotten old, he wasn't called up. Somebody once told me that, since good lefthanded pitching is scarce, you should not give up on a lefty until he's at least 31 years old. Tommy was 31. In 1959, he went 12-8 for the Royals. Still, no callup, as the Dodgers rebounded to win their 1st Pennant and World Series in California.

In 1960, which turned out to be the Royals' last year -- they became the Syracuse Chiefs and a Minnesota Twins farm team the next season -- it all fell apart for Tommy, as he lost his control, going 2-5 with an 8.20 ERA. He was released on July 9. At 33, he was done as a player: His minor-league record was 136-104, but in the majors, he went 0-4, with an ERA of 6.48, and a WHIP of 1.869. Better than Koufax, huh?

*

Well, his baseball career might have ended there, except that Al Campanis, who had been a Montreal teammate of his, was now the Dodgers' scouting director, and he immediately hired Tommy as a scout. By 1966, he was managing in the Dodgers' farm system, with the Pocatello Chiefs. He was quickly moved up to the Ogden Dodgers, and stayed with them until finally going to the Spokane Indians as their manager in 1969.

In 1972, the Indians were moved to New Mexico, to become the Albuquerque Dukes. That year, Tommy managed them to the PCL Pennant. In 1973, in the off-season for American baseball, he managed the Tigres del Licey to the Pennant in the Dominican Winter Baseball League.

That got him brought back to the big-league Dodgers, as 3rd base coach for the 1973 season. It made him the front-runner to succeed Walter Alston as manager. Alston had managed the Dodgers since 1954, and before that had managed the Royals (including Tommy). Knowing that he was the front-runner, Tommy turned down other managing offers. (While the Yankees changed managers after the 1973 season and in mid-1975, team owner George Steinbrenner did not offer him the job.)

On September 29, 1976, Alston retired, and Tommy Lasorda was named manager with 4 games to go in the regular season. In his 1st full season, 1977, his Dodgers dethroned the Cincinnati Reds' "Big Red Machine" as NL Western Division Champions, and beat his hometown team, the Philadelphia Phillies, in the NL Championship Series. He had won a Pennant.

The World Series would be against the Yankees, now managed by Billy Martin. As the teams were introduced before Game 1 at Yankee Stadium, the 2 hotheaded Italians ignored their 1956 brouhaha, and shook hands as competitors and mutual admirers. The Yankees won in 6 games.

You want to hear something stupid? In 1978, when I was 8 years old, I thought baseball managers wore uniform numbers based on how they finished. Billy Martin wore Number 1. Tommy Lasorda wore Number 2. Martin's Yankees beat Lasorda's Dodgers in the previous year's World Series. So, that's how it worked, right? If the Dodgers had won, Lasorda would have wore 1, and Billy would have worn 2.

Then, when Billy, ahem, was allowed to resign in mid-1978, and Bob Lemon was hired as manager, he didn't take Number 1. He took the number he'd always worn as a major league pitcher, 21. I didn't get it.

Then, when Billy, ahem, was allowed to resign in mid-1978, and Bob Lemon was hired as manager, he didn't take Number 1. He took the number he'd always worn as a major league pitcher, 21. I didn't get it.

The Dodgers would again win the Division, beat the Phillies in the NLCS, and face the Yankees in the World Series. One big difference was that, after an emotional meltdown by Martin, Bob Lemon was now the Yankee manager.

They beat the Yankees in Games 1 and 2 at Dodger Stadium. The Yankees won Game 3, but the Dodgers were winning Game 4, 3-0, with 1 out in the bottom of the 6th inning. They were 11 outs away from taking a 3-games-to-1 lead. That's when one of the screwiest plays in memory happened.

Reggie Jackson, whose 3 home runs in Game 6 clinched the previous year's Series, singled home a run. Thurman Munson took 2nd base on the play. Then Lou Piniella came to bat. Sweet Lou hit a low line drive toward shortstop Bill Russell.

It's important to remember that this ball was very low. If it had been any higher, the umpires would probably have invoked the infield-fly rule, which would automatically have declared the batter, Piniella, out for the 2nd out of the inning, and forced Munson to stay at 2nd and Jackson at 1st.

But there was no time for the IFR to be called, and Russell… dropped the ball. Thurman saw this and headed for 3rd. Russell recovered the ball, and stepped on 2nd to force out Reggie, who was stuck just off of 1st, seemingly frozen. Russell threw to 1st, and, the ball hit Reggie on the leg, and caromed away into foul territory. Lou got to 1st safely. Thurman rounded 3rd and scored. The Yanks now trailed 3-2, with Lou on 1st and 2 outs.

Lasorda stormed out of the dugout, and furiously argued with the umpires' crew chief, American League ump Marty Springstead, that Lou should be called out due to Reggie's intentional interference.

Springstead decided that he could not determine Reggie's intent, and he let the result of the play stand. Lasorda would later say he was impressed with Reggie's presence of mind to attempt the "tactic," which becomes known as "the Sacrifice Thigh," but he still thought it was an illegal play.

The Yankees tied the game in the 8th and won it 4-3 in the 10th, tying the Series at 2 games apiece. They won Game 5 in The Bronx and Game 6 in L.A., to take the title.

Game 4 of the 1978 World Series still ticks off Dodger fans. They still believe that if Reggie hadn't interfered with the ball, the Dodgers would have won the game and the Series. They claim they can see him sticking his hip out to deflect the ball on the replay. They need to get their vision checked. Umpires from both Leagues determined that there was no intentional interference. So we can also rule out AL bias.

Also, the Dodgers were still winning. After the run scored, it was Dodgers 3, Yankees 2. What's more, the Dodgers were up 2 games to 1. The Dodger bullpen could have held that lead, and they would then have had 3 chances to get 1 win. Even after losing the game, the Series was still tied. They had 3 chances to get 2 wins, with Game 6 and, if necessary, Game 7 at Dodger Stadium. Instead, they blew a 2-0 lead in games. The Dodgers flat-out choked, and the Yankees happily took advantage of this.

Does Lasorda deserve some blame? He lost his cool. I don't blame him for arguing the call, because a manager needs to stand up for his team when he believes they're being wronged. But, as they say in English soccer, he lost the plot, and his team followed his lead.

Furthermore, the Yankees were better. They were the defending World Champions, having beaten the Dodgers the year before. They had won 100 games to the Dodgers' 97, and in a tougher Division, too. They had a better lineup, a better defense, a better starting rotation, a better bullpen, and a calmer manager in Bob Lemon.

Let's face it: Even if Reggie had been called out, and the inning ended, there's no guarantee that the Yankees still wouldn't have come from behind to win. This was a team that did what it had to do to win.

Furthermore, the Yankees were better. They were the defending World Champions, having beaten the Dodgers the year before. They had won 100 games to the Dodgers' 97, and in a tougher Division, too. They had a better lineup, a better defense, a better starting rotation, a better bullpen, and a calmer manager in Bob Lemon.

Let's face it: Even if Reggie had been called out, and the inning ended, there's no guarantee that the Yankees still wouldn't have come from behind to win. This was a team that did what it had to do to win.

The Dodgers did not win the Division in 1979. In 1980, they lost a 1-game Playoff for the title to the Houston Astros. Finally, in 1981, they beat the Yankees to win the World Series for the 1st time in 16 years. Lasorda had his 1st real World Series title.

*

But he had already become very popular after winning a Pennant as a rookie manager. He told the media, "I bleed Dodger Blue." When rookie Mexican pitcher Fernando Valenzuela took baseball by storm in 1981, Lasorda called his habit of looking up to the sky in mid-windup "looking to The Big Dodger in the Sky" -- in other words, suggesting that God as a Dodger fan.

He was so well-liked that, after a 3-home run performance by Dave Kingman of the Chicago Cubs against the Dodgers in 1978, he was asked about it, and let loose a torrent of profanities, and the media laughed it off as a personality trait. If Martin had done it, it would have been considered evidence of a mind having long been lost.

Like Martin, Lasorda enjoyed emphasizing his Italian-ness. He said his favorite food was "anything ending in a vowel." He also palled around with Frank Sinatra, as had Brooklyn-era Dodger manager Leo Durocher. Tommy kept a framed photo of himself with Frank in his office.

Durocher once said, "It's Frank Sinatra's world,

the rest of us only live in it."

Whatever Lasorda thought of Durocher,

he clearly agreed with him on this.

Being the personable manager of a successful team in a big market soon made Lasorda national a media darling. The Los Angeles Times loved him. So did NBC, which often booked him on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and on Bob Hope's specials.

NBC also always interviewed him for its Saturday Game of the Week, as did ABC for its Monday Night Baseball -- this at the dawn of ESPN, before there was Baseball Tonight and nationally-televised ballgames every day of the week.

In the early 1980s, to see a game that did not feature your local team -- or, as in the cases of the New York, Chicago, Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay areas, one of them -- was only possible once or twice a week. Other than that, unless your local TV affiliate happened to get footage from another city the same night, in order to see a highlight -- say, an especially long home run, or a no-hitter -- you had to wait until the syndicated This Week In Baseball aired before your local team's Sunday afternoon game.

With this in mind, NBC took 2 of the biggest stars in the game, and put them together: Lasorda and Reds superstar Johnny Bench. From 1980 to 1985, before its Saturday Game of the Week, the network aired The Baseball Bunch, an instructional show hosted by Bench. Each week, a different current baseball star, or sometimes an all-time great, would guest-star as they taped in Tucson, Arizona, which enabled them to tape near several Spring Training camps. The pilot episode featured the biggest name on the Dodgers, 1st baseman Steve Garvey.

Lasorda appeared remotely, as the turban-wearing "Dugout Wizard." This meant that he could dispense his baseball wisdom without being on-set. This meant that not only did he not have to interact with opposing players that he didn't like, but he also didn't have to interact with another regular on the show, The Chicken, the former San Diego Padres mascot played by Ted Giannoulas.

Lasorda hated mascots. With the Dodgers facing the Phillies at Veterans Stadium on August 28, 1988, he saw the Phillie Phanatic dressing a dummy in a Dodgers Number 2 jersey. He stormed out of the dugout, took the doll, and hit the Phanatic with it. Needless to say, the Philly boo-birds let him have it.

On August 23, 1989, at the Olympic Stadium in Montreal, Lasorda complained to the umpires about Expos mascot Youppi! -- and crew chief Bob Davidson threw him out of the game, making Youppi! the 1st mascot ever ejected.

Lasorda kept winning, but only to a point. In 1983, he guided the Dodgers to another Division title, but the Phillies finally beat him in the NLCS. In 1985, he won another Division, but lost the NLCS to the St. Louis Cardinals, in large part because he trusted reliever Tom Niedenfuer, who had no pitch but a fastball, and had already given up a walkoff home run to Ozzie Smith in Game 5 in St. Louis, to pitch to Jack Clark, who took one halfway across the San Gabriel Mountains in the 9th inning of Game 6 to give the Cards the Pennant.

In 1988, the Dodgers had NL Most Valuable Player Kirk Gibson, NL Cy Young Award winner Orel Hershiser (who set a new record with 59 consecutive scoreless innings), and little else. But they won the Division, and upset the Mets in the NLCS. Gibson was hurt, but convinced Lasorda to let him pinch-hit with a man on in the bottom of the 9th in Game 1 of the World Series against the Oakland Athletics, with the A's leading 4-3. Gibson hit a home run to win the game, 5-4, and the Dodgers went on to win the Series in 5 games.

It would be Lasorda's last Pennant. He had a near-miss for the Division title in 1991, losing to the Atlanta Braves on the last weekend. The Dodgers were leading the Division in 1994, when the Strike hit. The Dodgers won the Division in 1995, but got swept by the Reds in the NL Division Series.

On June 23, 1996, at Dodger Stadium, the Dodgers beat the Astros 4-3. The next day, Lasorda had a heart attack. For years, his pasta-rich diet and his weight had been an issue. He did commercials for Ultra Slim-Fast, and lost 38 pounds, and looked a lot better. But, by this point he had gained it all back. And now, at the age of 68, his life was genuinely in danger.

Former shortstop Bill Russell, by then one of his coaches, served as interim manager, until July 29, when Lasorda officially retired. Until then, for 43 seasons, the team had had just 2 managers: Walter Alston and Tommy Lasorda, as many managers as they'd had home cities -- but had 16 postseason appearances, 11 Pennants and 6 World Championships.

Lasorda had achieved 8 of those postseason berths, winning 7 Pennants and 2 World Series. He had won 1,599 games against 1,439 losses, for a winning percentage of .526. In postseason play, he was 31-30, for .508.

"I made guys believe," he said in a 2013 interview. "I made them believe they could win. I did it by motivating them. I was asked all the time, 'You mean baseball players that make $5 million, $8 million, $10 million a year need to be motivated?' They do. That's what I did."

*

He was no longer the manager, and was no longer under the same kind of stress. But he was hardly retired. The Dodgers immediately named him a team vice president. He served as an interim general manager in 1998. For the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia, he was appointed manager of the U.S. team, and he led them to the Gold Medal.

In 1997, his 1st year of eligibility, he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. In connection with this honor, the Dodgers retired his Number 2, and named a street at their "Dodgertown" Spring Training complex in Vero Beach, Florida "Tommy Lasorda Lane." In 2014, as part of renovations to Dodger Stadium, a restaurant named Lasorda's Trattoria opened.

At the 2001 All-Star Game in Seattle, he was named to the coaching staff. In a freak occurrence, Vladimir Guerrero swung and lost his bat, and it went flying toward Lasorda in the 3rd base coaching box. He tried to get out of the way, and fell flat on his ass. He was 73 years old, and fatter than ever. People were worried that he was seriously hurt. He wasn't.

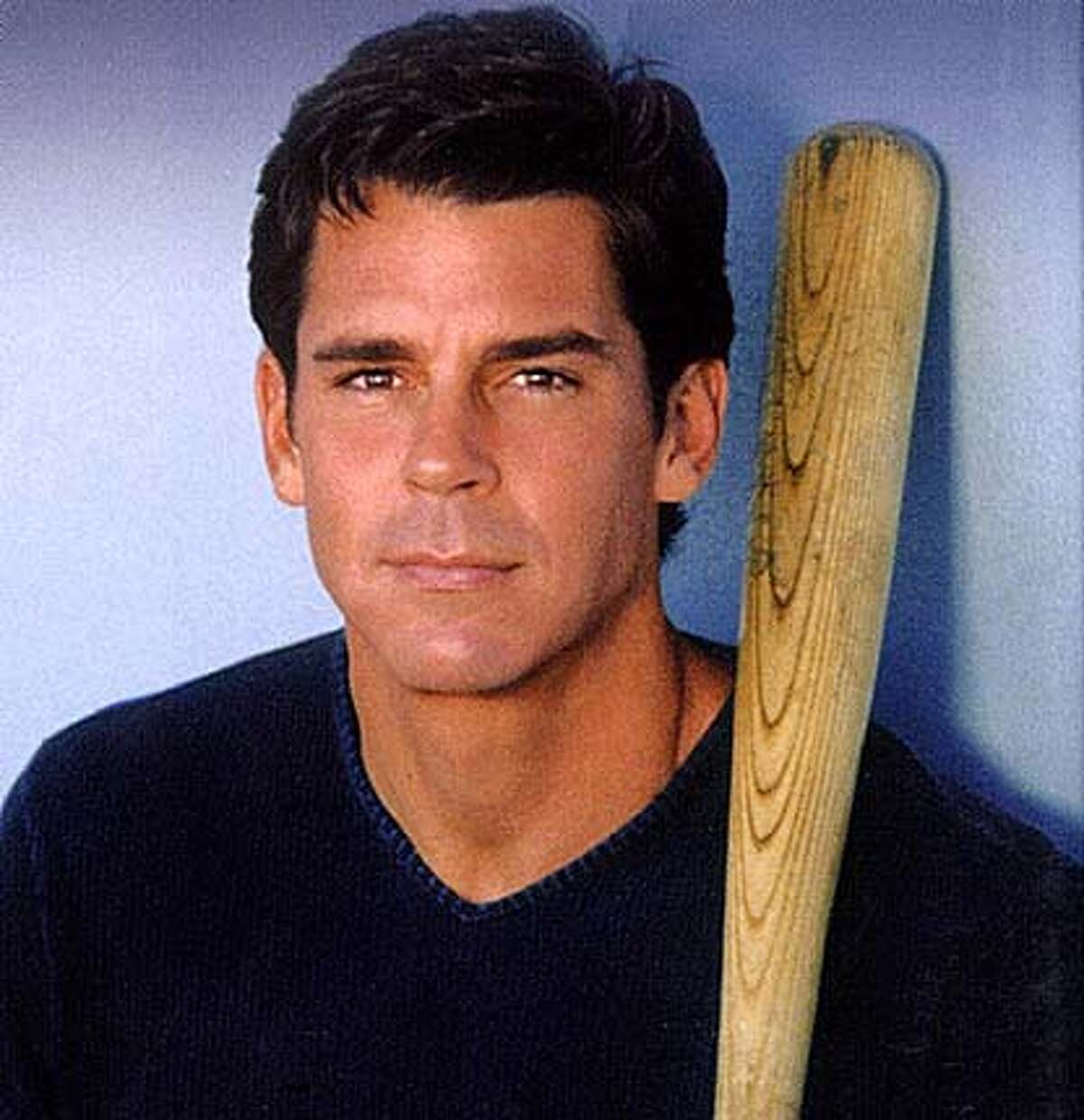

He was like a father to so many of his players. His former teammates included high school classmate Vince Piazza, who named one of his sons Thomas and named Lasorda the boy's godfather. Another of his sons was drafted by the Dodgers in a very late round, solely because Lasorda asked. That was Mike Piazza, who became a superstar, first with the Dodgers, then with the Mets. Another Lasorda teammate was Ralph Avila, grandfather of Alex Avila, a Minnesota Twins catcher. Lasorda was his godfather, too.

As for his own children, well, that was another story. He met his wife Jo while he was playing in the minor leagues, in her hometown, Greenville, South Carolina. They were married for 70 years. They had a daughter, Laura, who has a daughter, Emily Goldberg.

He also had a son, Thomas Charles Lasorda Jr. He was a good athlete, and was nicknamed "Spunky." But he was also gay, and Tommy Sr. couldn't handle that. Tommy Jr. became friends with Dodger outfielder Glenn Burke, whose teammates knew he was gay. Dodger 2nd baseman Davey Lopes said, "No one cared about his lifestyle." Lasorda cared, and on May 17, 1978, the Dodgers traded Burke to the A's for fellow outfielder Bill North.

Father and son were close. When the Dodgers were at home, Tommy Jr. would visit the clubhouse. When they were on the road, Tommy Sr. would call his son, at a time when a long-distance call was still a big deal.

But Tommy Sr. refused to see the truth. Cat Gwynn, a high school classmate of Tommy Jr., said, "It was very obvious that he was feminine... He wasn't at all uncomfortable with who he was... He strutted his stuff." (Apparently, it never occurred to the father that "Spunky" might not be a good nickname for his son.)

But, like so many other young gay men in the 1980s, Tommy Jr. contracted AIDS. He did whatever he could. He stopped dating. He quit illegal drugs. He took every new drug that was recommended to combat the virus. He went to the gym more often. In the end, it did no good. He died on June 3, 1991, at the age of 33.

A magazine writer did a profile on him the following year, and Tommy Sr. was furious. Not only did the father insist that his son wasn't gay, but that his cause of death was pneumonia. The latter claim wasn't a complete delusion. Nobody really dies from AIDS, but rather from complications from it, including cancer. HIV does affect the lungs, and so, frequently, one of those complications is pneumonia.

Did Tommy Sr. ever accept the truth about Tommy Jr., and his own anti-gay bigotry? Only he knew for sure. What he did do was seek comfort in the game he loved: "When I walk into the clubhouse, I got to put on a winning face. A happy face. If I go in with my head hung down when I put on my uniform, what good does it do?" And he funded an athletic complex in the Los Angeles suburb of Torrance: The Tommy Lasorda Jr. Field House.

Tommy Lasorda had a 2nd heart attack in 2012, but recovered. But on November 8, 2020, he had a 3rd, and was hospitalized. He was released on January 5, but, as it turned out, he was not out of the woods. Yesterday, January 7, 2021, he had a 4th heart attack, and was taken to a hospital near his home in suburban Fullerton, California. He died there, at the age of 93.

He was a people person, as long as you were his kind of people. If you weren't, he had no use for you. But he loved baseball, and I have to give him credit for that.

UPDATE: He was buried at Rose Hills Memorial Park, in the Los Angeles suburb of Whittier, California.

No comments:

Post a Comment