Joe DiMaggio presented him with a Plaque that would be placed on the center field wall, near the flagpole and the Monuments to Miller Huggins, Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Mantle presented DiMaggio with a similar Plaque, which DiMaggio did not know was going to happen. Each of these Plaques was replaced with a Monument after the player in question died.

The original plaques, now at the Yogi Berra Museum

"Baseball has been very good to me," Mantle told the fans, "and playing 18 years in Yankee Stadium for you folks is the best thing that could ever happen to a ballplayer."

The worst thing was having it come to an end. Mickey's drinking, already indulged before he was old enough to legally do so, increased after his father died in 1952, and increased further as his injuries piled up. Now that he no longer had to stay in shape to play, it had gone from bad to worse.

In the movie 61*, Whitey Ford (played by Anthony Michael Hall) asks Mickey (Thomas Jane), "Hey, Slick, how come every time you get drunk, it ends up costing me money?"

Eventually, Mickey realized, "I was telling the same old stories, and I saw how much I was drinking in them, and I realized they weren't funny anymore." In 1993, a doctor told him, "Mickey, your next drink might be your last."

Cover date: April 17, 1994

He went into the Betty Ford Center, and was able to stop drinking. But it was too late. He developed liver cancer, and he was given a liver transplant -- on June 8, 1995, the anniversary of his Day. He became an advocate for organ donation, as well as against drug and alcohol abuse, doing more good with the last 2 months of his life than with the first 63 years. But his cancer had spread, and he died on August 13, 1995.

At his press conference after his transplant, he said, "This is a role model: Don't be like me." At his funeral, Bob Costas described him as "a fragile hero to whom we had an emotional attachment so strong and lasting that it defied logic." He added: "In the last year of his life, Mickey Mantle, always so hard on himself, finally came to accept and appreciate the distinction between a role model and a hero. The first, he often was not. The second, he always will be. And, in the end, people got it."

Mickey's drinking was wrong. But it was not incomprehensible.

Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame Mickey Mantle for Becoming an Alcoholic

5. Unfair Expectations. "Everybody said I was going to be the next Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio, all rolled into one," Mickey said. "And it just didn't happen."

Mickey's rookie season, 1951, was difficult, for several reasons. But his statistics for the next 4 seasons would have been just fine by most people's standards. He batted .300 or better in 1952, '54 and '55. In all 4, he had at least 21 home runs and 87 RBIs.

In '54, he has his 1st 100+ RBI season, and led the American League in runs scored. In '55, he led the AL in home runs, triples, walks, on-base percentage and slugging percentage.

His OPS+'s in those seasons were 162, 144, 158 and 180, meaning he was 62 percent better at producing runs than the average hitter in '52, 44 percent better in '53, 58 percent better in '54 and 80 percent better in '55. And he did all of this on one good knee, before his 24th birthday.

For comparison's sake, the player considered the best in baseball in 1954 and '55, and the man to whom Mickey was most often compared, Willie Mays of the New York Giants, had an OPS+ of 175 in '54 and 174 in '55. In other words, Mickey wasn't that far behind Willie in '54, and was better in '55. (Willie spent most of '52 and all of '53 in the U.S. Army, due to the Korean War.)

What about the other great center fielder in New York City in the early 1950s, Duke Snider of the Brooklyn Dodgers? From '52 to '55, he had OPS+'s of 135, 165, 171 and 169.

So, in '52, with Willie unavailable, Mickey was 27 percent better than the Duke, despite the Duke having Ebbets Field to hit in. In '53, with Willie unavailable, the Duke was 19 percent better than Mickey. In '54, Mickey was 17 percent behind Willie, and 13 percent behind the Duke. In '55, Mickey was 6 percent better than Willie and 11 percent better than the Duke.

The guys then considered the best hitter in each league? Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox and Stan Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals? Ted was also serving in Korea, in his case as a fighter pilot for the U.S. Marine Corps. His OPS+ for '54 was 201, and for '55, 209. So Mickey was 43 and 29 percent behind him.

Stan the Man was available for all 4 of those seasons. His OPS+'s were 167, 169, 167 and 157. So, in those seasons, Mickey was 5 percent behind, 25 percent behind, 9 percent behind, and 23 percent ahead.

It's important to keep age in mind. Mickey was so easily comparable to Willie not just because they were in the same City, playing the same position, but they debuted the same year, and were only 5 months apart in age.

In contrast, Mickey was 5 years younger than the Duke, 11 years younger than Stan, and 13 years younger than Ted. Ted and Stan were only a few years younger than DiMaggio, so they were in his generation, not in that of the 3 New York center fielders of the '50s.

Mickey was, if not yet obviously better than Ted, Stan, Willie and the Duke, at least on a level where comparing him to them would not be ridiculous. And he was younger than all of them, and had already dealt with more injuries than any of them would in their entire careers. In other words, comparing Mike Trout to Mickey Mantle, as some people now do, would be fair if you compare Trout to Mantle as of 1955 -- and, even then, Mickey had already won 4 Pennants to Trout's none so far.

And all this was before the next 2 seasons, 1956 and 1957. He won the Triple Crown in '56 -- something Ted did twice, but none of those others did -- and the Most Valuable Player award both times. (MVPs in a career: Mickey 3, Joe D 3, Stan 3, Ted 2, Willie 2, Duke none.)

And still, it wasn't enough for some people. They wanted Mickey to be even better. Better than what? Better than who? Better than Ruth? Better than Gehrig? Better than DiMaggio? Better than Ruth, Gehrig and DiMaggio? Wasn't it enough that he was roughly on the same level as Mays, Snider, Williams and Musial? Wasn't it enough for him, before turning 24, to be 1 of the top 5 players in the game? Apparently, for some people, it wasn't enough.

And before his 24th birthday, on one good knee, Mickey had already helped the Yankees win 4 Pennants and 3 World Series. Those other guys? Well, the Duke would go on to win 7 Pennants and 2 World Series in his career. The other 3 guys combined would win 9 Pennants and 4 World Series.

So, before turning 24, Mickey Mantle had already surpassed the expectations one could reasonably have for just about any other player who ever lived. And still, he got booed when he limped up to the plate.

And Alex Rodriguez thought he had it bad at Yankee Stadium?

Bitch, please.

So if, at the end of the night, if Mickey Mantle wanted to have a drink or two, or more, who could blame him?

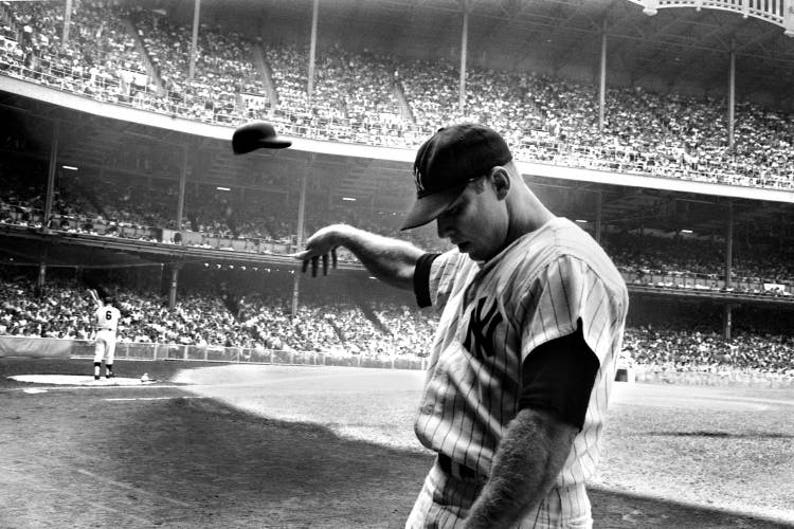

4. Injuries. A common excuse used by people who drink to excess is that "It kills the pain." No athlete had more pain than Mickey Mantle. As this chart following his 1963 broken foot shows, he had already sustained 17 separate injuries in 13 seasons, plus 1 in high school.

The broken foot of 1963 cost him 2 months, June 4 to August 4, the longest he was ever out. But, for long-term effect, the 2 biggest injuries were the knee he tore up in the 1951 World Series, while still a teenager for a few more days; and the shoulder injury he got in 1957, on his throwing arm, at age 25. He played another 11 seasons, in pain every day.

If drinking alcoholic beverages truly did ease pain, then maybe Mickey drank enough, and maybe he didn't. Of course, it doesn't truly ease pain, and drinking on that level causes far more problems than it solves, which is none.

I'm reminded of an episode of M*A*S*H, where Radar (played by Gary Burghoff) was having a bad day, and Hawkeye (Alan Alda) and B.J. (Mike Farrell) offered him a drink from the distillery in their tent. Radar tasted it, and hated it. He said, "I thought you guys drank this stuff because it makes you feel good." And B.J. told him, "No, it's supposed to make you feel nothing."

And they were doctors, not patients. Which leads to the other familiar excuse for drinking to excess: "I drink so that I can forget." Certainly, Mickey had things he wanted to forget, emotional pain that he wanted the drinking to dull. More about that in a moment.

3. Baseball's Double Standard. Teams, and the radio and TV networks broadcasting them, took advertising revenue from breweries and distilleries.

In the Yankees' case, it was Ballantine beer, leading to broadcaster Mel Allen calling a home run "a Ballantine blast." When the Yankees replaced their scoreboard in 1959, they sold the old one to the Philadelphia Phillies, and now they advertised Ballantine, too. Of course, the new Yankee Stadium scoreboard also had a Ballantine ad.

Don Larsen's perfect game, Game 5 of the 1956 World Series.

Mickey hit a home run and made a game-saving catch.

Falstaff sponsored the Chicago White Sox, the Giants after they moved to San Francisco, and the Los Angeles/California Angels. The Baltimore Orioles and the Washington Nationals, National Bohemian, or "Natty Boh." The Boston Red Sox, Narragansett. The Chicago Cubs, Old Style. The Cincinnati Reds, Hudepol. The Detroit Tigers, Stroh's. The Kansas City Athletics, Schlitz. The Milwaukee Braves, Miller High Life. The Minnesota Twins, Hamm's. The Pittsburgh Pirates, Iron City Beer. "If Carling did... " Well, they did do baseball, sponsoring the Cleveland Indians.

Hell, the St. Louis Cardinals were owned by Gussie Busch, who owned Anheuser-Busch Brewery, and essentially bought the Cardinals because he wanted to use their giant radio network to advertise Budweiser. It worked: When Gussie bought the Cardinals in 1953, Bud was not one of the top 10 beer brands in America. When they won their next World Series in 1964, Bud was Number 1, and a lot of the brands mentioned above were on their last legs, although they've since been brought back on a local basis.

So in the midst of all this alcohol advertising at ballparks and on baseball broadcasts, did anybody in baseball really have the moral authority to tell Mickey Mantle that he shouldn't drink booze?

Mickey did a commercial for "Lite Beer From Miller," as Miller Lite was then called, with Whitey Ford. Then the noted switch-hitter switched to Miller's competitor, Anheuser-Busch Natural Light, doing one of a series of commercials featuring malaprop-prone comedian Norm Crosby and ex-athletes.

Yankee broadcasts were also sponsored by White Owl cigars, so a home run could also be "a White Owl wallop." Mickey smoked, but not nearly as much as he drank. If Billy Crystal's film 61*is telling the truth, Mickey told Roger Maris that his smoking meant that he shouldn't be criticizing anyone's drinking.

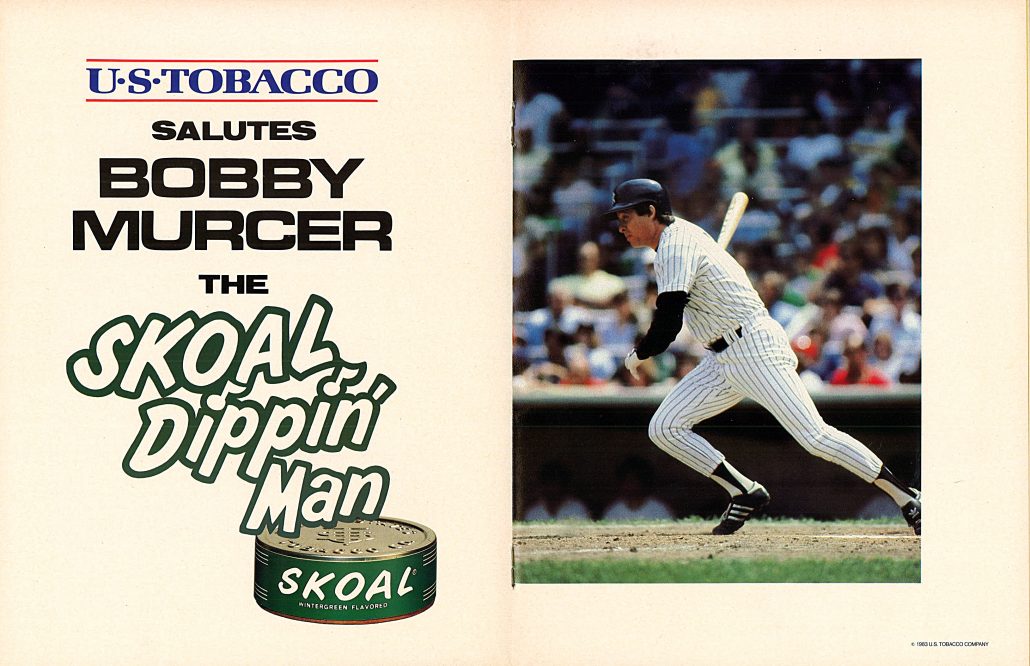

Tobacco advertising on American television and radio would not be banned until 1971. But, let the record show that, among Mickey's teammates, Maris died from cancer at age 51, and Bobby Murcer, who not only chewed tobacco, but even sang in commercials, "I'm a soul-dippin', Skoal-dippin' man," died of cancer at 62, both younger than Mickey.

No, I wasn't kidding. Note the musical notes dotting the I's.

Then again, DiMaggio died of lung cancer, but he was 84. Mickey's first manager, Casey Stengel, was also a noted boozer, and he lived to be 85. Mays was a smoker in his playing days, and he's still alive, at age 88.

2. Mental Health Treatment, 1950s Style. This was not the golden age of mental health. When a celebrity was checked in for psychiatric treatment -- or for alcohol or drug rehab, for that matter -- it was publicized that the person was being "treated for exhaustion." Sometimes, it was listed as "nervous exhaustion."

Jimmy Piersall, a great-field-okay-hit outfielder for the Red Sox in the 1950s, was committed to an asylum for what would now be called bipolar disorder. Hollywood actually made an effort to treat it with dignity, casting Anthony Perkins as Piersall in Fear Strikes Out. This was in 1957, the same year that Joanne Woodward became a star as a patient with a split personality, which we would now call disassociative identity disorder, in The Three Faces of Eve. The fact that these films stand out so much is telling.

Jimmy Piersall

Fear Strikes Out typecast Perkins to the point where he was the only guy who could play Norman Bates in Psycho. Let's face it: If there had been a Batman TV show even 5 years earlier, and they were doing it seriously, like such crime shows of the era as The Untouchables and Naked City, Perkins would have been the easy choice to play the Joker.

Anthony Perkins as Jimmy Piersall in Fear Strikes Out

But how did Piersall's opponents treat him? Pretty badly. Everybody called him "Crazy." In the Ike Age, admitting to V.D. would have been better received than admitting to mental health difficulties.

You think I'm exaggerating? After the 1957 season, Philadelphia Phillies 1st baseman Ed Bouchee -- a fair player, but not as good as Piersall, let alone Mantle -- was arrested for exposing himself to underage girls. He was committed, sentenced to 3 years' probation, and permitted to rejoin the Phillies in the middle of the next season. And he didn't seem to have been given a hard time by opponents or fans, even in boo-riddled Philly. When did I learn this story? In 2006. To his credit, Bouchee lived until 2013, and, as far as is publicly known, never had another such incident.

So what was Mickey supposed to do? Tell a psychiatrist that he was depressed? That losing his father so early had affected his thinking? That the booing was getting to him? That the physical pain led to psychological pain? That he wasn't strong enough inside to put it all aside and simply show how strong he was outside by hitting the ball farther than anybody since Ruth?

Could he have told his teammates those things? No. Somebody would have had a big mouth, violated "the sanctity of the clubhouse" and failed to "let it stay here when you leave here," and it would have gotten back to Yankee management. And they would have ignored it -- if he was lucky. Yankee management publicized that Mickey endured his pain. They talked about his "courage." Today, we say somebody has courage if they do seek mental health treatment.

Back then? That wasn't "The Yankee Way." The Yankee Way was enduring pain, stoically. Like DiMaggio with his bad heel. Like Gehrig, knowing he was dying and still calling himself "the luckiest man on the face of the Earth."

Like Ruth, suffering from throat cancer, telling a crowd, "You know how pained my voice sounds? Well, it feels just as bad," and then changing the subject to how great a game baseball is, and saying, "There's been so many lovely things said about me, and I'm glad that I've got the opportunity to thank everybody. Thank you."

Complain about your physical pain? Complain about your emotional pain? What are you, a sissy? Get over to Toots Shor's and have a few scotches. That's what a man does: Go out drinking with the boys.

A photo of Mickey Mantle and Bernard "Toots" Shor together,

at Toots' Midtown bar, is not unusual.

One of Mickey and his wife Merlyn together at a bar is.

Which brings us to...

1. Toxic Masculinity, 1950s Style. We hear that phrase "toxic masculinity" a lot now. But Mickey's career, 1951 to 1968? That was the golden age of it. You grew up in the Great Depression, and you fought in World War II? Or, you grew up with the rationing of WWII and fought in the Korean War? Now, you were going to enjoy your middle-class (or better) manhood to the hilt.

The TV show Mad Men was set, mostly in New York, from 1960 to 1971, as this world began to change. The TV show Life On Mars was set in New York in 1973, and it accurately showed that, while this mindset had been weakened, it was far from crumbling.

Did it really matter if a Democrat (Harry Truman, 1945-53; or John F. Kennedy, 1961-63; or Lyndon Johnson, 1963-69) or a Republican (Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1953-61) was in the White House? Not if you were a straight white Christian male age 21 and up. Heck, you could be Jewish, and still get away with a lot of that kind of behavior, as long as you weren't "too Jewish."

As comedian Bill Maher has put it, "On a resume, a man could list 'sexual harassment' under 'Special Skills.' And nobody ever asked you to check your privilege. You didn't have to check. It was there, all right."

Nobody batted an eye early in Goldfinger (released on September 18, 1964, a few days before Mickey's last World Series appearance) when Sean Connery, playing James Bond, dismissed Dink, his girlfriend-of-the-moment (Margaret Nolan), when CIA Agent Felix Leiter (Cec Linder) came over, by saying, "Dink, say goodbye to Felix. Man talk," and then slapped her on the ass. James Bond: The Man. He drinks. He smokes. He screws women he wants, and hits women he doesn't want.

Incidentally, the Hays Code, which prohibited a lot of things, and the early Bond films barely got approval with their "adult situations," had no problem with the particular act of Bond slapping Dink on the ass. But, just in the last few years, this sort of thing has gone from being classified as "sexual harassment" to being classified as "sexual assault."

Let the record show that, while Mickey had a serious drinking problem, and was a serious womanizer (which I did not know before he died -- though I read ex-teammate Jim Bouton's Ball Four and knew about the Peeping Tom stuff, a.k.a. "beaver shooting"), no one has ever publicly accused him of hitting a woman, or "taking advantage of her," as the expression of the time went.

Who told Mickey that what 1950s American society said that a man -- or "a real man" -- did was wrong? Nobody. He had a father, Elvin "Mutt" Mantle, a dirt-poor miner who taught him to play, love and respect baseball; but also taught him how to drink, and likely didn't teach him anything about respecting women. Mickey had brothers, who were no help.

When he got to the Yankees, there were new "father figures," who did little to disabuse him of these notions. Joe DiMaggio? He wasn't an alcoholic, but he wasn't exactly on the straight and narrow. He fooled around, and palled around with mobsters. He was just more discreet about it. Casey Stengel? He tried to tell Mickey, "Being with a woman all night never hurt no professional ballplayer. It's running around all night looking for one that does him in." Message received: Don't run around all night to bar after bar. Stick to one bar, and...

And Mickey's new "brothers," his Yankee teammates? Phil Rizzuto and Yogi Berra were happily married men who liked to go out with the boys, but who also knew their limits with booze, and didn't get into trouble, of any kind. That was no fun. So Mickey hung out with guys who did get into trouble, and didn't care that they had wives who wanted them to come home before it got too late: Billy Martin and Whitey Ford.

"I roomed with Phil Rizzuto, Yogi Berra and Mickey Mantle," Billy said. "They all won the MVP. How bad an influence could I have been?" Billy was traded in 1957, and Mickey said, "Turned out, Whitey was the bad influence on me."

And, as the movie 61* showed, Roger Maris did try to tell Mickey that he was drinking too much. But Mickey told him that, given how much he was smoking, and his smoking was getting worse the closer he got to both the home run record and the end of the season, he had no place to talk. But smoking was also something that "a real man" did in those days.

Mickey would later admit that Roger was the best man he ever knew, and that he'd want his kids to grow up to be like Roger, not like himself.

Instead, all 4 sons -- Mickey Jr., Billy (named for Martin), David and Danny -- became alcoholics, too. All 4 eventually got clean, although Billy died in 1994, shortly after Mickey got out of Betty Ford, triggering fears that he would fall off the wagon. He didn't. Mickey Jr. died in 2000. David is now 63, the same age Mickey was when he died, and Danny is 59. Merlyn died in 2010.

*

On Old-Timers' Day 1995, Mickey was too weak to attend, so he made a video message. He said, "When I died, I wanted on my tombstone, 'A GREAT TEAMMATE.' But I didn't want it this soon." That caption appeared on his Monument, dedicated the next year.

So now, we have to reach a verdict. The case for the defense is that Mickey had all of these things against him, and their combination was overwhelming. The case for the prosecution is that he still had a choice, and he chose the option that led to drink and dissolution.

But what if someone -- perhaps someone more responsible, like Rizzuto or Berra -- had told him early on, "Mickey, you're gonna get in trouble if you keep drinking like that"? Would he have listened? Or would he still have caved in to those less responsible?

Here's testimony from Mickey's surviving sons, David and Danny, in response to an unflattering book that was published in 2009:

Was dad an alcoholic? Yes, he could be unruly sometimes and say rude things but alcohol does that to people. It makes a person say and do things that they normally wouldn’t do and say. When he acted rude towards people, he later deeply regretted it. So for these writers and other people to keep bringing up this issue is actually good because it points out why he got help in the first place. Was he a bad father? No. He never left his family and always made sure we were well taken care of. He had a heart of gold, always thinking of others. After his father passed, with dad at the young age of 21, he assumed the high pressure role of family provider and took care of everybody including his mother, brothers, sister, and his in-laws.

We are so proud to call him our dad. From the time he co-wrote his original biography “The Mick” in 1985 until his final days when he said “I am not a role model”, he was completely honest and open about his life. While in the Betty Ford Clinic, he received tens of thousands of cards and letters of support and thanks. His actions became an inspiration to others with the same problem which meant a lot to dad. He has no idea how many people have come up to us and expressed their sincere appreciation for the example he set in seeking help for his alcoholism.

With that in mind, is it fair to find him Guilty?I'm afraid it is. If he really wanted to be "a role model," as we now define that phrase, he could have kept his drinking in moderation early on, and perhaps he could have lived longer. Only another year and change, and he would have seen the beginning of the 1996-2003 dynasty. Another 15 years? He would have been just past his 78th birthday when the Yankees won the 2009 World Series at the new Yankee Stadium.

"You couldn't possibly approve of Mickey Mantle," the legendary New York sportswriter Roger Kahn wrote. "What you could do was love him."

Plea-bargain. Find him guilty of the lesser charge of giving in to peer pressure. But suspend the sentence. The man suffered enough in life. And it was hardly all his own fault. Let him have peace in death, where he can play on heavenly grass in center field, and hit home runs, and run around the bases as fast as he wants.

No comments:

Post a Comment