Dwight Clark, Bill Walsh and Joe Montana at Candlestick Park, 1982.

Walsh and Montana made Clark famous.

Clark made Walsh and Montana Super Bowl-bound.

A person should not have his or her life limited to the perception of one moment in it. But sometimes, one moment can make us remember your life forever.

Dwight Edward Clark was born on January 8, 1957 in Kinston, North Carolina, and grew up across the State in Charlotte. He was a quarterback in high school, but Clemson University tried to convert him into a defensive back. He was unhappy, and they moved him to wide receiver.

In 1978, with Steve Fuller as quarterback, he helped them go 11-1, beat Ohio State in the Gator Bowl (where his teammate Charlie Bauman was punched by Ohio State coach Woody Hayes, leading to his firing), and were ranked 6th in the final poll.

Clark caught only 33 passes in college, 11 in his senior year. But Bill Walsh, head coach of the San Francisco 49ers, saw something in him, and drafted him in the 10th round. (Today, the NFL Draft only has 7 rounds.)

The 49ers were terrible, going just 2-14 in Clark's 1st season, as they had the season before. But it was also Walsh's 1st season, and he was building one of the greatest teams of all time. Included in this was another rookie, Notre Dame quarterback Joe Montana.

The 49ers improved to 6-10 in 1980, but no one except Walsh saw the 1981 season coming. After dropping 2 of their 1st 3 -- losing away to Detroit by 7, beating Chicago at home, and losing away to Atlanta by 17 -- the Niners went on a tear, winning 12 of their last 13, the only loss by 3 at home to Cleveland, a pretty good team at the time, and taking their 1st NFC Western Division title in 9 years.

Included in that run was a 17-10 win over the Giants at Candlestick Park. They hosted the Giants again in the Divisional Playoff, and beat them 38-24. This set up their 3rd appearance in an NFC Championship Game. The 1st 2 had been in 1970 and 1971, both against the Dallas Cowboys, and they lost both. They had made the Playoffs again in 1972, and again lost to the Cowboys.

(The 49ers had also lost the 1949 All-America Football Conference Championship Game to the Cleveland Browns, and a 1-game Playoff for the 1957 NFL Western Division title to the Detroit Lions. Until 1981-82, those had been their only trips to the Playoffs, in any league.)

Now, they welcomed the Cowboys again to windswept Candlestick. The Niners had home-field advantage. The Cowboys had experience, with most of them having played in the previous season's NFC Championship Game, a loss to the Philadelphia Eagles; and some having played in Super Bowls XII (a win over the Denver Broncos) and XIII (a loss to the Pittsburgh Steelers).

The game was a seesaw affair. The 49ers led 7-0, then the Cowboys led 10-7 at the end of the 1st quarter, then the 49ers led 14-10, then the Cowboys led 17-14 at the half, then the 49ers led 21-17 at the end of the 3rd quarter. This included a touchdown pass from Montana to Clark.

The Cowboys kicked a field goal at the start of the 4th quarter, to make it 21-20 San Francisco, then added a touchdown to make it 27-21 Dallas. With 4:54 left in the game, the 49ers got the ball at their own 11-yard line. They had given up 6 turnovers, including 3 interceptions by Montana. This would have been cited as the reason they had lost -- if they had lost.

Montana went to work. Lenville Elliott dropped a pass, then ran for 6 yards. Montana threw a 6-yard pass to Freddie Solomon. First down. Elliott ran for 11 yards, for a 1st down, then another 7, then let another Montana pass slip through his hands. He was seemingly setting himself up to be the scapegoat, and he might have remained so, had the Cowboys not been caught offside on the next play, giving the 49ers a 1st down.

Montana threw a 5-yard pass to Earl Cooper, the unintentional symbol of the team, as he wore Number 49. This brought the game to the 2-minute warning. Montana called a reverse, and handed off to Solomon, who ran for 14 yards and a 1st down. Montana threw to Clark for 10 yards, 1st down. Then he threw to Solomon for 13 yards and a 1st down at the Dallas 12. They called their 1st timeout. Montana looked to Solomon in the end zone, but it went incomplete. Elliott ran for 6 yards, bringing the ball to the Dallas 6.

San Francisco called its 2nd timeout, with 58 seconds on the clock. It was 3rd and 3. If the next play failed, there was still time to call timeout -- or to use the stoppage of the clock if it were an incomplete pass -- and get a 1st down and then a winning touchdown, but a field goal wouldn't be enough. It had to be a touchdown.

Walsh told Montana to run "Sprint Right Option," a play he adapted from one he learned as an assistant coach to Paul Brown on the Cincinnati Bengals, which Brown had run successfully with quarterback Otto Graham on the 1950s Browns. Earlier in the game, the play had resulted in a touchdown pass from Montana to Solomon. Walsh figured that would work again.

Maybe it would have, if Solomon hadn't slipped while running his route. There are so many things the loss could have been blamed on, if the 49ers had lost and blown their best chance to date of winning a title. To make matters worse, the Cowboys broke through the 49ers' offensive line. Ed "Too Tall" Jones, Larry Bethea and D.D. Lewis of the "Doomsday Defense" all came toward Montana.

It would later be said of Montana, "He sees the whole field." He knew he had the mobility to get out of this, and the awareness of where his receivers (now including his running backs) were so that he could get the ball to them. I like to compare him to another blond legend of a game called "football," the legendary Dutch forward for Arsenal, Dennis Bergkamp.

Clark's job on the play was to block, but with Solomon having slipped, there was no one to block for. Instead, he got into the end zone. Everson Walls saw this, and covered him. Montana thought he could get the ball to Clark. He executed a perfect pump-fake, and Jones, at 6-foot-9, was not too tall for this play: In this case, his height was a disadvantage, as he jumped to block and possibly intercept a pass that never came, and couldn't get back down in time to get back into position to chase Montana.

Montana jumped and threw. It looked like the ball would go over the end zone. But Clark, who later denied that it was a throwaway, that it was a backup plan for such a play that they had practiced, jumped and caught it in the corner. Touchdown.

"I don't know how I got up there," he said after the game. "Maybe it was God, or something."

Walter Iooss Jr. of Sports Illustrated, already considered perhaps the greatest photographer in sports history, got the picture that ended up on the cover and in everyone's memory. It's an iconic image, even though, due to his arm and his facemask, you can't see his face.

Ray Wersching kicked the all-important extra point, and it was San Francisco 28, Dallas 27. There were still 51 seconds left. But the Cowboys could only run 2 plays from scrimmage, and Lawrence Pillers caused a fumble while sacking Danny White well short of game-winning field-goal range. Jim Stuckey recovered it, and the 49ers were headed to their 1st NFL championship game of any name.

Candlestick Park stood for 54 years, hosting the baseball Giants for 40 seasons, the 49ers for 43 seasons, and the Beatles' last official concert in 1966. Unless you want to count holding firm during the 1989 World Series earthquake and saving 60,000 lives, and hosting the Bay Area's coming-together a week later, this was the much-maligned stadium's greatest moment. As Clark said, "It was dump, but it was our dump, so we could talk about about it, but we didn't want anybody else to talk bad about it."

As with Willie Mays in the 1954 World Series, when the baseball Giants were still in New York, before moving to San Francisco, Clark's grab became known as simply "The Catch."

The 49ers advanced to Super Bowl XVI, at the Pontiac Silverdome in the Detroit suburbs. By a weird twist, the opponent was Walsh's former employer, the Cincinnati Bengals, still owned but no longer coached by Paul Brown, who taught him "Sprint Right Option." Forrest Gregg, who won 5 NFL Championships with the Green Bay Packers and a 6th with the Cowboys, coached them. The 49ers won, 26-21. Clark was not much of a factor, not catching a single pass. But he had won a ring.

He had also earned his 1st Pro Bowl bid, and earned his 2nd the next season, leading the NFL in receptions. The 49ers returned to the NFC Championship Game in the 1983 season, but lost to the Washington Redskins. But they went 15-1 in 1984, and won Super Bowl XIX. In that game, Clark caught 6 passes for 77 yards, as the 49ers beat the Miami Dolphins 38-19.

Clark retired after the 1987 season, having been replaced as a receiving target by both Jerry Rice and John Taylor. He finished his career with 506 receptions for 6,750 yards and 48 touchdowns. Not enough, perhaps, to get into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, but enough for the 49ers to retire his Number 87, their 1st honoree from their 1980s teams that won 4 Super Bowls before adding another in the 1994 season.

"The Catch" was a hinge moment in NFL history. Before it, the Cowboys had been one of the League's dominant teams, reaching 11 NFL or NFC Championship Games in 16 years, including 5 Super Bowls, winning 2; while the 49ers had made the Playoffs only 5 times in the previous 35 years. Over the next 14 seasons, the 49ers would go 5-0 in Super Bowls, while the Cowboys would struggle for several years. The rivalry would be renewed in the 1990s, as they faced each other in 3 straight NFC title games, the Cowboys winning in 1992 and '93 and the 49ers in '94.

Everson Walls, meanwhile, spent several years trying to live down his ineffectiveness in preventing "The Catch." But in the 1990 season, he helped the Giants reach Super Bowl XXV, and win it, finally getting a ring.

*

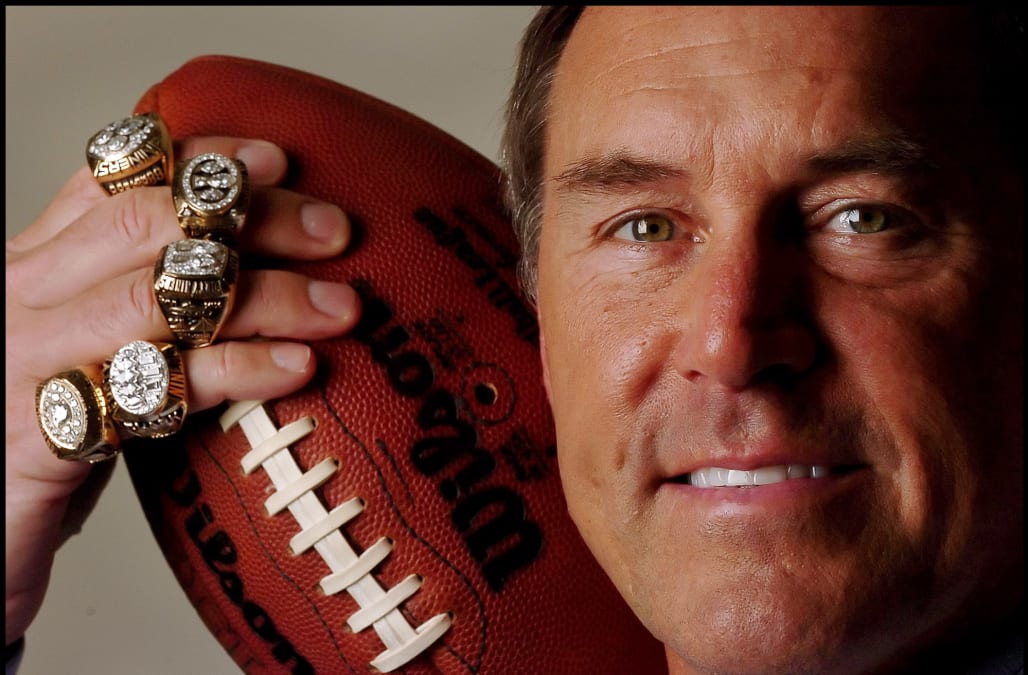

After retiring as a player, Clark was hired in the 49ers' front office. He was awarded rings from their victories in Super Bowls XXIII, XXIV and XXIX. In 1999, when the Browns began their restoration, former 49ers executive Carmen Policy was running them, and hired Clark to be general manager. Things didn't go well there, and Clark resigned after 3 seasons, becoming a postgame analyst on SportsNet Bay Area's 49ers coverage.

He married and divorced Ashley Stone, having daughter Casey and sons Riley and Mac. Casey married Peter Harrold, who played for the Los Angeles Kings and the New Jersey Devils.

In 2011, Clark married Kelly Radzikowski, and lived in Santa Cruz, which is considerably closer to the 49ers' new home, Levi's Stadium in Santa Clara, than it is to the site of Candlestick or to downtown San Francisco. Clark may have anticipated having a longtime job as a 49ers studio analyst, and thus living somewhere convenient to work.

If so, he was tragically mistaken. On March 19, 2017, he annouced that he had been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, known by its initials ALS, but best known for the earlier sports legend who suffered from it: Lou Gehrig's disease. It's awful: It kills neurons that control voluntary muscles, resulting in the muscles stiffening, twitching and shrinking. Eventually, victims lose the ability to speak, swallow, and finally breathe.

Gehrig died just 2 years after being diagnosed. Physicist Stephen Hawking died earlier this year, over 50 years after being diagnosed, and after 30 years of being almost completely immobile. So its "progress" varies.

Other sports figures known to have had it: Football layers Kevin Turner, Orlando Thomas, and Canadian star Tony Proudfoot; Yankee Hall of Fame pitcher Jim "Catfish" Hunter, 1949-51 Heavyweight Champion Ezzard Charles, and soccer legends Don Revie and Jimmy "Jinky" Johnstone.

From outside sports: Chinese dictator Mao Zedong, Vice President Henry Wallace, Blues singer Huddy "Lead Belly" Ledbetter, actor and singer Dennis Day, songwriter Bob Haymes, jazz musician Charles Mingus, actor David Niven, General Maxwell Taylor, former Senator Jacob Javits of New York, former Governor Sidney P. Osborn of Arizona, former Governor Paul Cellucci of Massachusetts, playwright Sam Shepard, Toto bassist Mike Porcaro, British comedian Ronnie Corbett, actor Lane Smith, soap opera star Michael Zaslow, and professor Morrie Schwartz, immortalized by his former student, Detroit sports columnist Mitch Albom, in his book Tuesdays with Morrie.

More to the point, 3 players from the 49ers' 1964 team developed ALS: Running back Gary Lewis, dead in 1986 at 44; linebacker Matt Hazeltine, dead a month after Lewis, at 53; and quarterback Bob Waters, dead in 1989 at 50. Some people speculated that something to do with Candlestick caused it, but that now appears to have been a dead end. After all, until Clark, no other 49er had been diagnosed.

But enough players now have that a link has been suggested between ALS and the the brain condition chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which can only be definitively diagnosed after death. Players who've developed ALS have usually had repeated concussions, which has also been a cause of CTE.

Clark had 3 concussions while playing. "I've been asked if playing football caused this," he said. "I don't know for sure. But I certainly suspect it did. And I encourage the National Football League Players Association and the NFL to continue working together in their efforts to make the game of football safer, especially as it related to head trauma.

Dwight and Kelly Clark moved to rural Whitfish, Montana, where he died on June 4, 2018, at the age of 61.

Some of us only knew Dwight Clark for a moment. But because of that moment, we will remember him forever.

UPDATE: Clark was buried at Candy Bar Ranch in Kalispell, Montana.

No comments:

Post a Comment