Around 2:00 in the morning, I found out about Darren Daulton. Jack Fritz, a producer at Philadephia all-sports station WIP (94.1 on your FM dial), tweeted, "Darren Daulton was the epitome of a baseball player. Wish I was around to fully appreciate him."

I told him, "He was a blood & guts catcher who wouldn't accept quitting, a Thurman Munson type."

Darren Arthur Daulton was born on January 3, 1962 in Arkansas City, Kansas. He was drafted by the Phillies in their World Series-winning year of 1980, and reached the major leagues on September 25, 1983, shortly before they won another Pennant. Wearing Number 29, he was a defensive replacement for Ozzie Virgil in the 9th inning of a 6-5 Phillies win over the St. Louis Cardinals at Busch Memorial Stadium.

He spent all of 1984 and most of 1985 in the minors, then was called up late in the 1985 season, given Number 10. But Virgil, and after 1986 Lance Parrish, stood in his way. It was not until 1989 that he became the Phillies' regular starting catcher.

On August 15, 1990, he caught a no-hitter pitched for the Phillies by Terry Mulholland. He batted .268 that year. But he really struggled with the plate otherwise: .204 in 1985, .225 in 1986, .194 in 1987, .208 in 1988, .201 in 1989 (his 1st full season), and .196 in 1991.

Then came 1992, a breakout year for the man called Dutch. He batted .270, hit a career-high 27 home runs, and led the National League with 109 RBIs. He made the NL All-Star Team for the 1st of 3 times. The Phillies still finished last in the NL Eastern Division.

But 1993 was the "Worst to First" year, the year of "Macho Row," what broadcaster Harry Kalas called "this wacky, wonderful bunch of throwbacks." Like the 1986 Mets before them, and the 2004 Boston Red Sox "Idiots" after them, they were a bunch of slobs with bad hair and worse personal habits: Daulton, Mulholland, Lenny Dykstra (who also played for the 1986 Mets), Dave Hollins, Jim Eisenreich, Pete Incaviglia, Mitch Williams, Danny Jackson, Larry Andersen, and a young, already effective, but also already annoying Curt Schilling. Jim Fregosi, who had managed the California Angels to the American League Western Division title in 1979, was their manager.

The exemplar of this was John Kruk, the big bearded 1st baseman. A female reporter saw him smoking a cigarette at his locker, and she asked him, "How can you smoke as an athlete?" And the Krukker said, "I ain't an athlete, lady. I'm a baseball player." (Kruk even titled his memoir I Ain't an Athlete, Lady.)

No, those Phillies didn't look like baseball players. But when they played baseball, they sure as hell looked like a baseball team. They won 97 games. For comparison's sake, the Pennant-winning Phillies of 1915 won 90 games; the 1950 "Whiz Kids," 91; the 1964 team that blew a sure Pennant in the last 2 weeks, 92; the 1980 team that won the whole thing, 91; the 1983 Pennant winners, 90; the 2007 Division winners, 89; the 2008 World Champions, 92; the 2009 Pennant winners, 93. In Phillies history, the only teams with more wins than the 1993 Macho Row are the 2011 Division winners with 102; and the 1976 and 1977 NL East winners, each with 101. The 2010 Division winners also won 97.

William Kashatus is a Philadelphia-area college professor and historian who's written several books about baseball, especially the Phillies, including Macho Row: The 1993 Phillies and Baseball's Unwritten Code. He said in today's Philadelphia Daily News:

He was both physically and mentally tough, a man's man. Daulton made teammates accountable and, in 1993, provided uncontested leadership for a colorful and irreverent band of throwbacks who went from worst to first in the National League East and restored some respectability to a franchise that had become a perennial loser.

The Atlanta Braves were 2-time defending Pennant winners, and were expected to beat the Phillies easily. And when the Phillies needed 10 innings to win Game 1 and the Braves won 14-3 in Game 2 to take a split at Veterans Stadium, and then won Game 3 in Atlanta, it looked bleak.

"Bleak, my ass," he seems to be saying.

"We're gonna win this thing."

But the Braves didn't win another postseason game for 2 years: The Phils won Game 4 2-1, took Game 5 4-3 in 10 innings, and then came home to win Game 6, 6-3. It was only the 5th Pennant in the franchise's 111-season history.

The Phillies lost the 1993 World Series to the Toronto Blue Jays, having blown a 14-9 lead in the 8th inning at home in Game 4, and then a 6-5 lead in the 9th in Toronto in Game 6. But, like the 1951 New York Giants, the 1959 Chicago White Sox, the 1965 Minnesota Twins, the 1967 and 1975 Boston Red Sox, the 1984 San Diego Padres, and since then the 1995 Cleveland Indians and the 2005 Houston Astros, it seems to have been enough that they won the Pennant. There are, of course, what-ifs, but few real recriminations. Phillies fans even forgave Mitch Williams for giving up the Joe Carter home run that won the Series, giving him a standing ovation every time he's returned to Veterans Stadium and now Citizens Bank Park.

"We played hard, and did everything yard," Daulton said of the 1993 Phillies. "It was fun, and that was what made us special."

*

On the other hand, maybe it would have been better for the Phillies if they'd given it a good run in 1993, and come up short, finishing 2nd. They might have had more drive if they'd had more to prove. Instead, 1994 was a year of injuries, including to Daulton, who was on paces for career highs in batting average (.300), home runs (15) and RBIs (56) before getting hurt 67 games in.

The strike then hit, and by the time baseball resumed in late April 1995, the Phillies were already a very different team. Between players and management, they acted less like a team that had unfinished business, and more like a team that thought, "We had one shot, and we gave it our best, and we gave everyone a thrill."

Daulton was pretty much done as a productive player at age 33. He played through pain in 1995, and only appeared in 5 games in 1996. With the emergence of Mike Lieberthal, Dutch became expendable. (Lieberthal is the Don Mattingly of Philadelphia: The Phillies won the Pennant in 1993, and won the Division in 2007, but didn't make the Playoffs in between -- Lieby's entire Phillies career.)

On July 21, 1997, the Phillies traded him to the Florida Marlins for Billy McMillon. a journeyman outfielder who never had more than 150 plate appearances in a season, and only played 24 games for the Phillies that year, but did reach the postseason with the 2001 and 2003 Oakland Athletics.

He didn't look right in a Marlins uniform.

Then again, nobody ever has, not even Jeff Conine.

Daulton was now an outfielder, and batted .263 with 14 home runs and 63 RBIs. His Macho Row teammate, Jim Eisenreich, had also been acquired. The Marlins were in only their 4th season, but owner Wayne Huizenga was going for broke, trading for as much talent as he could, knowing he was going to break it all up after the season. Daulton batted .389 with 2 doubles, a home run and 2 RBIs in the World Series, and the Marlins beat the Indians in 7 games.

Huizenga did break up the Marlins, and they lost 108 games in 1998, a disgusting total for a team past its 4th year after expansion, let alone a team that had won it all the year before. Knowing something like this would happen, Dave Rosenbaum wrote a book about the Marlins, titling it If They Don't Win It's a Shame. Still, they did give South Florida a title, which Macho Row was not able to give the Delaware Valley.

Knowing that it wasn't going to get any better than that, Daulton retired as a World Champion, with a .245 lifetime batting average, 137 home runs, and the admiration of the baseball world. In 2003, when Veterans Stadium closed after 33 seasons, Phillies fans chose him ahead of Lieberthal, Bob Boone and Tim McCarver as the catcher on the "All-Vet Team." In 2010, the Phillies inducted him into the Philadelphia Baseball Wall of Fame.

That year, he also began a pregame show on WPEN, then the Phillies' flagship radio station. He continued to do this show through the 2016 season, by which point his condition made it impossible.

Like several of those Phillies, he had legal issues. On 3 occasions, he was busted for drunk driving. He also ran up a lot of unpaid speeding tickets. He lost 2 marriages. He also began to talk about odd things, claiming, "I like to astral travel, teleport, travel through time." In 2007, he published a book about the occult and his claimed experiences, titled If They Only Knew.

When "the end of the Mayan Era," December 21, 2012, approached, and some people thought it was "the end of the world," Dutch said they were a little off: "December 24, 2012, by the way. That's the number. As 7 billion people, the world will rise to another level of consciousness."

People began to wonder what was going on in his head. As it turned out, there was something going on in his head. On July 1, 2013, he underwent surgery for brain cancer. Whether that had anything to do with his odd views is uncertain. What I do know is that he never recanted them.

But he did own up to his failings: "Anything I did in the past is my fault. Not my ex-wives' fault, not any of my kids' faults, not baseball, not the media. I did the damage. But I've also learned from it." He remarried, grew closer to his 4 children, quit drinking, and started the Darren Daulton foundation for brain cancer research. In early 2015, he announced that he was cancer-free.

But, as with so many other pronouncements regarding cancer, that turned out to be either premature or temporary. His condition returned this year. Darren Daulton died yesterday, in the Tampa Bay suburb of Clearwater, Florida, the Phillies' Spring Training home, at the age of 55. He was survived by his parents, Carol and Dave; his brother, Dave Jr.; his 3rd wife, Amanda Dick; daughters Summer and Savannah; and sons Zachary and Darren II.

"Darren was the face of our franchise in the early 1990s," David Montgomery, chairman of the group that owns the Phillies, said today. "Jim Fregosi asked so much of him as catcher, cleanup hitter and team leader. He responded to all three challenges."

Carli Lloyd, the world's greatest female soccer player, who grew up in the Philadelphia suburb of Delran, Burlington County, New Jersey, tweeted, "So sad. My all time favorite. Why I chose #10 jersey."

It wasn't because of any great soccer player. Not Pelé, not Diego Maradona, not Ronaldino, not Lionel Messi, not Michelle Akers. It was because of Darren "Dutch" Daulton. He reached her by crossing not just a river and a State Line, but by crossing sports, generations, and even genders.

Carli Lloyd was inspired by Darren Daulton, and wore Number 10 in his honor. Girls all over the world are being inspired by Carli Lloyd. If they only knew.

*

Then, this afternoon, I learned about Don Baylor. A very different player, with a very different personality. But also one of the game's leaders.

Don Edward Baylor (apparently, he was born "Don," not "Donald") was born on June 28, 1949 in Austin, Texas. He was the 1st black athlete at that city's Stephen F. Austin High School, and he was good enough at football that Darrell Royal offered him a scholarship, which would have made him the 1st black football player at the University of Texas, one of the greatest of all college football programs.

But baseball, then as now, paid more than pro football, and he enrolled at Blinn Junior College in nearby Brenham, and was drafted by the Baltimore Orioles in 1967. In 1970, playing for the Rochester Red Wings, he led the International League in doubles, triples and runs scored, and was a September callup for the eventual World Champion O's.

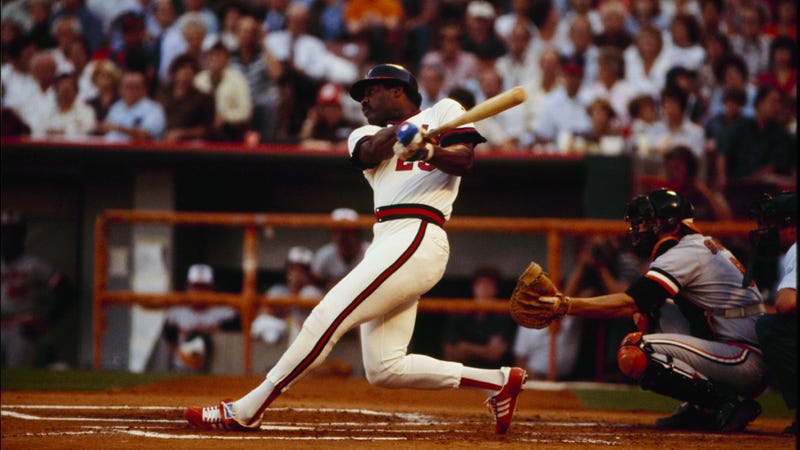

He made his major league debut on September 18, 1970. Batting 5th, wearing Number 23 and playing center field, his 1st at-bat resulted in an RBI single off Steve Hargan that drove in another Don B., Don Buford. He was vital to the game at the beginning, and at the end: In the bottom of the 11th, he singled home Paul Blair, to give the Orioles a 4-3 win over the Cleveland Indians at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore.

He led the IL in doubles for Rochester again in 1971, and again earned a late-season callup. In 1972, he was called up for good, wearing the Number 25 which would be his most familiar, and helped the O's win the American League Eastern Division in 1973 and 1974.

Gene Michael told this story about Baylor's toughness:

This was back in the Seventies, when I was with the Yankees and Donny was with the Orioles. I was playing second base instead of shortstop, when the ball was hit to Nettles at third, who bobbled it, prompting a late throw from me. Here was Baylor barreling down on me, and he slid right through me!

I turned around, he was about three feet past the bag, but the umpire called him safe. So I took after him and tagged him out, only to have Donny grab my arm like a vise. He later said he thought I was coming after him to fight him. But I never felt a grip so strong.

In 1976, he, Mike Torrez and Paul Mitchell were traded to the Oakland Athletics for Reggie Jackson, Ken Holtzman, and a minor leaguer. He became one of several players that A's owner Charlie Finley, in his everlasting cheapness, refused to keep as the first round of free agency came in the 1976-77 off-season. He then became one of several players that Gene Autry, the legendary entertainer who owned the team then known as the California Angels, opened the vault for and signed. (Joe Rudi also went from Oakland to Anaheim this way, and Autry also signed Baylor's ex-Baltimore teammate Bobby Grich.)

Despite having played his career thus far in pitcher's parks -- Memorial Stadium, the Oakland Coliseum, and now Anaheim Stadium (now named Angel Stadium of Anaheim), the man nicknamed "Groove" was quite strong, and hit 34 home runs in 1978. In 1979, he had his best season, reaching career highs with a .296 batting average, 36 home runs and 139 RBIs. He led the AL in RBIs and runs scored. Incredibly, this would be the only season in which he was selected for an All-Star Team.

The Angels were managed, as I said, by Jim Fregosi, and they reached the postseason for the 1st time, winning the AL Western Division. Their opponents in the AL Championship Series were Baylor's former team, the Baltimore Orioles, whose right fielder Ken Singleton was the other possible choice for the AL's Most Valuable Player. The O's won the series in 4 games, so Singleton got the Pennant (but not the World Series, as the O's were beaten by the Pittsburgh Pirates), but Baylor got the MVP.

He was injured in 1980, and missed a big chunk of the season. He was lucky not to be injured much more often: He was hit with 267 pitches. Only Hugh Jennings before him (287) had been hit with more, and only Craig Biggio since him (285) has.

But he was tough. 267 HBPs, and not once did he rub the spot where he was hit. Ken Griffey Sr. said that when Don was hit, the trainers would put the ball on a stretcher, and carry it off the field.

In 1982, he again helped the Angels win the AL West, but they lost the ALCS to the Milwaukee Brewers. He signed with the Yankees, and in 1983 batted .303, which turned out to be the only one of his 1979 career highs he ever beat. He had 21 home runs and 85 RBIs in 1983, 27 and 89 in 1984, and 23 and 91 in 1985.

That season, Billy Martin sent him up to pinch-hit to prevent the final out in a game against the Chicago White Sox, as the tying run with 2 men on. He gave the ball a ride, and it might have been out in any ballpark but the old Yankee Stadium, where it got hung up in its left-center "Death Valley." It was the last out -- of Tom Seaver's 300th win. I was there.

Baylor was now 36, and team owner George Steinbrenner may have thought he was done. Just before the 1986 season began, he traded Baylor to the Boston Red Sox for Mike Easler. This trade made no sense, as they were essentially the same player: Righthanded-hitting left fielders with some power, and Easler was only a year younger. Easler had a good year for the Yankees, but Baylor had a better one for the Sox, hitting 31 homers with 94 RBIs, and helping them win the Pennant. Of course, they lost the World Series to the Mets in crushing fashion, and Baylor going 2-for-11 in the Series didn't help.

Late in the 1987 season, after the trading deadline but meeting the waivers requirements, the Red Sox traded Baylor to the Minnesota Twins for a minor leaguer. At 38, he looked done, and he didn't do much for the Twins down the stretch. But they won the AL West, and the Pennant. This time, he went 5-for-13 with a homer and 3 RBIs in the World Series, and the Twins beat the St. Louis Cardinals. In his 18th major league season, Don Baylor finally got his ring.

The Twins released him, and he signed as a free agent with the Oakland Athletics. He batted just .220, with 7 homers and 34 RBIs in what amounted to half a season's worth of plate appearances. But it was enough to help them win the AL West. They won the Pennant, but lost the World Series to the Los Angeles Dodgers. He didn't get a hit in the postseason, going 0-for-7. But he did achieve something no other player has, before or since: He appeared in the World Series in 3 straight seasons with 3 different teams.

He then retired, with a lifetime batting average of .260, 2,135 hits, including 366 doubles, 28 triples, and 338 home runs. He has been elected to the Angels Hall of Fame, but he's 2 or 3 steps below Cooperstown consideration.

*

He was immediately hired as the hitting instructor for the Brewers, and he served as such for the Cardinals as well. In 1993, he was named the 1st manager of the expansion Colorado Rockies. He had them in position to make a run at the NL Wild Card in the 1st season in which that was possible, 1994, but the strike ended that hope. He got them the Wild Card in 1995, in only their 3rd season -- until Daulton's '97 Marlins, the soonest any team had gotten to the postseason since 1903. He was named NL Manager of the Year.

He remains Rockies manager until being fired after the 1998 season. The Atlanta Braves hired him as hitting instructor under Bobby Cox in 1999, and they won the Pennant, making it his 4th trip to the World Series -- his 6th, if you count his brief '70 and '71 Oriole callups.

The Chicago Cubs hired him as manager in 2000, and they kept him for 3 seasons. In 2003 and '04, he was the Mets' bench coach under manager Art Howe. In 2005, he was Seattle Mariners bench coach under Mike Hargrove. In 2007, he became a Washington Nationals broadcaster. In 2009, he returned to the Rockies as hitting instructor, and they won the Wild Card again. In 2011, he was hitting instructor for the Arizona Diamondbacks, and they won the NL West.

In 2014, he returned to the team now named the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, and they won the AL West. It was the 14th time a team that employed him had reached the postseason. He was not rehired after the 2015 season, and that was his last job in baseball.

It may have been just as well: He was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2003, and had been battling it ever since. He returned to his native Austin in 2015, and died today, at the age of 68. He was survived by his 2nd wife, Rebecca Giles; his son, Don Jr.; his brother, Doug; his sister, Connie; and 2 granddaughters.

Claire Smith, who just became the 1st woman and the 4th black person ever to receive the Baseball Hall of Fame's J.G. Taylor Spink Award, tantamount to Hall of Fame election for sportswriters, was a friend of Baylor's, knew he didn't have long, and mentioned him in her acceptance speech in Cooperstown last weekend. Today, she wrote this:

How is it that one person can be known as one of the most intimidating players to ever wear a major league uniform and as one of the game's all-time gentle giants?

Both descriptions fit Don Baylor perfectly, seamlessly, throughout his 19-year playing career and beyond.

Singleton, whom Baylor beat out for the '79 MVP, tweeted, "Very sad last few days as baseball loses 2 strong leaders of the past, Darren Daulton & Don Baylor. Two old school tough baseball players."

Dutch and Groove. I don't know how well they knew each other, if at all -- Daulton's Phillies and Marlins were not among the many teams to have sought Baylor out -- but now they can play again. If it's on opposite sides -- Daulton was a career National Leaguer, and Baylor played for only American League teams -- a word of suggestion, Dutch: Don't call for the inside pitch. He'll take it. Or, maybe, swing at it, and hit it out.

UPDATE; Daulton was buried in Memorial Lawn Cemetery in Arkansas City, Kansas. Baylor was buried at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin.

UPDATE; Daulton was buried in Memorial Lawn Cemetery in Arkansas City, Kansas. Baylor was buried at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin.

No comments:

Post a Comment