So let me go over some tributes that shouldn't have waited so long.

*

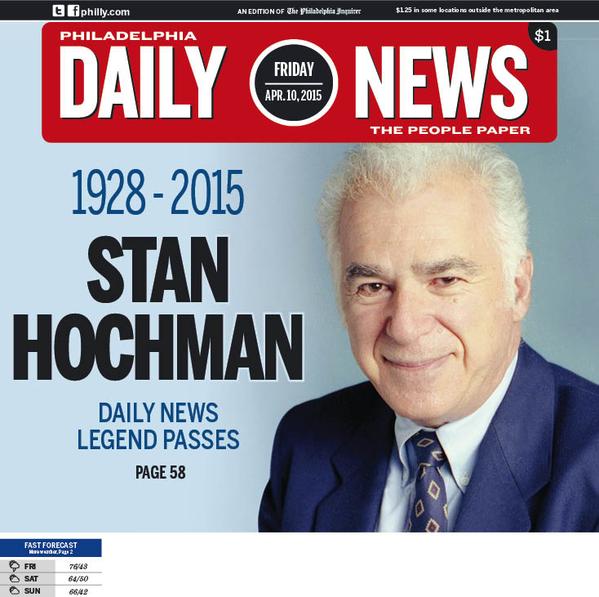

About some guys, you can say, "When they made him, they broke the mold." In the case of Stan Hochman, I think the mold dissolved.

Doug Collins, former Philadelphia 76ers star and head coach, said:

I have the utmost respect for Stan. I've known him since 1973. He was passionate about his work, and he knew his subjects. Before he would interview you, he did his homework so you knew that anything that he was going to write was done with due diligence. I consider him a dear friend.

Stan is Philly, through and through. When I think of all the writers that have come and gone through Philadelphia, that's what I think of. Stan and that voice. He was a throwback. He knew how to separate when to be a reporter and when to turn off the tape recorder. I understand the job that reporters have to do and sometimes it's not easy to ask the tough questions, the ones that need to be asked. Stan had a way of not only asking them so that you wanted to answer, but also made you feel better talking about it. He was tough, but fair. I always respected that.

Stan wasn't born in Philly, though. He was born in 1928 in Brooklyn -- which has a little-brother complex with Manhattan, and that might be why he understood Philly so well.

He went to New York University, and served in the U.S. Army during the Korean War. He joined the staff of the Philadelphia Daily News in 1959, and the only way he left was in a coffin, on April 9. He was 86.

He covered it all in the City of Brotherly Love (and Several Hatreds): The Eagles' 1960 NFL Championship and their 2 Super Bowl defeats, Wilt Chamberlain's 100-point game, the 1964 Phillies Phlop, the 76ers' titles under Wilt and Hal Greer in 1967 and Julius Erving and Moses Malone in 1983 (with Billy Cunningham as a rookie 6th man for the former and as head coach for the latter), Eagles fans booing Santa Claus, Philly's adopted son Joe Frazier rising to the Heavyweight Championship of the World, The Flyers' back-to-back Stanley Cups, the Phillies ending droughts with the 1980 and 2008 World Championships, Villanova's 1985 miracle, and the rise of sports-talk on radio and TV -- of which he became an integral part.

He covered games at Connie Mack Stadium, Franklin Field, Municipal/John F. Kennedy Stadium, the Philadelphia Civic Center, the Palestra, the Spectrum, Veterans Stadium, what's now known as the Wells Fargo Center, Lincoln Financial Field and Citizens Bank Park.

In 2009, he was interviewed for his 50th Anniversary with "The People Paper," and said this:

"Why do I keep doing what I do? The answer is, because I still enjoy it... I'm just a guy who truly enjoys what he's doing, in a city that cares deeply about its teams, but wants to read stuff that's 'tough but fair.'"

*

All of you have heard of baseball's racial-integration pioneers, Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby. Some of you have heard of the pioneers in other sports: Kenny Washinton and Marion Motley in the NFL; Willie O'Ree in hockey; and Chuck "Tarzan" Cooper, Nat "Sweetwater" Clifton and Earl "the Big Cat" Lloyd in the NBA. (Apparently, to be a racial trailblazer in the NBA -- well before there were the Portland Trail Blazers -- you needed a badass nickname.)

You may not have heard of Art Powell. But you should.

Unfortunately, I had not heard of Lloyd's death at the time, so let me get to him first.

Earl Francis Lloyd was born on April 3, 1928, in Alexandria, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. He played college basketball at West Virginia State, then an all-black school, and was drafted by the Washington Capitols in 1950. Their coach, Red Auerbach, a former star at George Washington University, liked that he was a D.C. guy. And Red didn't care about color, only talent and character.

The way it worked out, Cooper was the 1st black man drafted by an NBA team, the Boston Celtics; Clifton, a former Harlem Globetrotter, was the 1st one signed to a contract, by the Knicks; and Lloyd was the 1st one who actually got into a game, 1 day before Cooper and 4 before Clifton. It was Halloween Night, October 31, 1950, and the Nats lost to the Rochester Royals, 78-70. This was not a big surprise, as the Royals, forerunners of the Sacramento Kings, went on to win the NBA Championship that season.

The Caps were badly mismanaged, and owner Mike Uline's firing of Auerbach didn't help -- especially when Auerbach went to the Celtics and dragged the NBA into the modern world. The Syracuse Nationals picked Lloyd up, after he'd served in the Army (like Hochman, in the Korean War), and he helped them reach the NBA Finals in 1954, losing to the Minneapolis Lakers. In 1955, they won the title, beating the Fort Wayne Pistons in the Finals.

That tells you what the NBA was like in the Fifties: Cities the size of Rochester, Syracuse and Fort Wayne could reach the Finals, and no one thought that was shocking.

Lloyd ended his career with the Pistons, after they moved to Detroit, in 1960. He remained with the Pistons as an assistant coach. In 1965, general manager Don Wattrick wanted to make Lloyd the NBA's 1st black head coach. But he was overruled by ownership, and, instead, the head coaching job went to Dave DeBusschere -- later proven one of the sharpest minds in basketball, but, at the time, a 25-year-old player. What a massive insult to Lloyd.

He was, however, given the job in 1972, after Bill Russell and Lenny Wilkens had been named NBA head coaches, but didn't last long. He became an NBA scout. In 2003, because of his pioneering role, and also because he was one of the best players of his time, he was elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame. He died on February 26, at age 86.

*

Arthur Lewis Powell was born on February 25, 1937, in Dallas. and grew up in San Diego. He went to San Jose State, and played in the Canadian Football League, as did several other black players, knowing how many racist Southerners were playing in the NFL, and how few up there.

Powell was 1 of 2 notable rookies with the 1959 Eagles who didn't stick with the Eagles. The other was John Madden, who got hurt in preseason, was taught how to analyze football film by Eagles quarterback Norm Van Brocklin, and became a great coach and later broadcaster because of that.

Powell played for the Eagles in '59, but wasn't with them when they won the title in '60. They were scheduled to play an exhibition game with the Washington Redskins in Norfolk, Virginia, and found out that he and his black teammates weren't going to be staying at the same hotel as their white teammates. To make matters worse, his black teammates didn't want to do anything about it.

So he jumped the team, and signed with the New York Titans of the American Football League -- the team that became the Jets. In 1960, he led the AFL in receiving touchdowns. In 1962, he led it in receiving yards.

In 1963, having been traded to the Oakland Raiders, he led the AFL in both categories. (The Titans weren't unhappy with him, but they were desperate for cash, and the Raiders offered it.) In a league that put emphasis on the passing game, he was a big star. Indeed, it could be argued that he was the first star player in Jets' history, even if he was gone by the time the name was adopted for the 1963 season.

In 1963, a preseason game between the Raiders and the newly-renamed Jets was to be held in Mobile, Alabama. He found out the seating would be segregated. This time, he managed to get 3 black teammates to back him up, and they told Raiders GM Al Davis (not yet the owner) that they wouldn't play in a segregated stadium. Say what you want about the man that Al Davis became, but, on this occasion, he did the right thing: He backed his black players up, and the game was moved to Oakland.

In 1965, after the 1964 season, the AFL All-Star Game was scheduled for Tulane Stadium in New Orleans -- a city which then didn't have a team in either the NFL or the AFL. Powell and other black players were refused service by white taxi drivers and white nightclubs -- and this was a few months after the Civil Rights Act became law. Powell again organized, and 21 black players said they wouldn't play. The game was moved to Houston -- also a Southern city, but one which had already, through the AFL's Houston Oilers, accepted the black players as equals, so they knew it could be trusted.

Powell went to the Buffalo Bills in 1967, and, following the AFL-NFL merger, returned to the NFL in 1968, with the Vikings. Between both leagues, he caught 479 passes for 81 touchdowns -- an exceptional ratio. After the AFL was fully, uh, integrated into the NFL, and All-Time AFL Team was chosen, and Powell and Houston's Charlie Hennigan were selected to the Second Team. The First Team selections were Don Maynard of the Jets and Lance Alworth of the San Diego Chargers, both later elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Powell returned to Southern California, and ran a small oil company. He died on April 6, at the age of 78.

*

Jim Mutscheller was not as significant a pro football receiver as Art Powell. But he was important. After all, he was the 1st NFL player from the Pittsburgh satellite town of Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, and thus served as an inspiration for another man from that town, Joe Namath.

James Mutscheller -- no middle name, but he was nicknamed Bucky -- was born on March 31, 1930 in Beaver Falls. He went to Notre Dame, and was a sophomore on their 1949 National Championship team under Frank Leahy.

Yet another Korean War veteran, his NFL debut was delayed until 1954, when he became a tight end for the Baltimore Colts. He played 8 seasons with them, including the NFL Championship season of 1958 and '59, a target for the great quarterback Johnny Unitas. One of his catches was key to the Colts' winning drive in the 1958 NFL Championship Game victory over the Giants at the original Yankee Stadium.

He caught 220 passes for 3,685 yards and 40 touchdowns -- numbers that don't leap off the page today, but noticeable then. He was named an All-Pro in 1957.

After his playing career, Mutscheller stayed in the Baltimore area, living in Towson, Maryland, where he died on April 10. He was 85.

*

Eddie LeBaron was a big star in the NFL in the 1950s. A big one -- but not a tall one.

Edward Wayne LeBaron -- often incorrectly listed as Eddie Lee LeBaron -- was born on January 7, 1930 in San Rafael, California, north of San Francisco. He went to the College (now the University) of the Pacific in nearby Stockton and, after becoming yet another Korean War veteran, was ready to enter the NFL.

NFL GMs blanched at drafting 1984 Heisman Trophy winner Doug Flutie because he was just 5 feet, 9 3/4 inches. LeBaron was just 5-foot-7, yet he was one of the best quarterbacks of his time. After the Marines discharged him with a Bronze Star in 1952, he became only the 2nd starting quarterback the Redskins ever had following their 1937 move to Washington, succeeding the legendary Slingin' Sammy Baugh. He was a 4-time Pro Bowler.

In 1960, he became the 1st starting quarterback of the Dallas Cowboys -- and thus the 1st player to cross the divide of what eventually became the NFL's nastiest rivalry. After 4 seasons, in which the Cowboys were terrible (ah, the good old days), in 1963 he gave way to Don Meredith.

On October 9, 1960, the shortest quarterback in the NFL's modern era threw the NFL's shortest touchdown pass. The ball was 2 inches from the goal line, yet LeBaron dropped back to pass, and threw to Dick Bielski. The opponent? Oddly enough, the Redskins.

He became a lawyer, a broadcaster for CBS, and an executive with the Atlanta Falcons. He retired to Stockton, and died there this past April 1. He was a member of the College Football Hall of Fame, the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame, and, showing no hard feelings for his having gone to the Cowboys, the Washington Redskins Ring of Fame.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/45788798/635606234807286315-earl-loyd-piston-player-195.0.0.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment