Donald William Zimmer was born on January 17, 1931, in Cincinnati. As a boy, he saw his hometown Reds win the National League Pennant in 1939, then take the next step and win the 1940 World Series. At Western Hills High School, he was a star quarterback as well as a highly-regarded infielder.

He's one of 11 major leaguers to come from Western Hills, including Pete Rose, Karl "Tuffy" Rhodes, and the brothers Chuck and Eddie Brinkman. Another WHHS grad was Jim Frey, who, while he never reached the majors as a player, would manage the Kansas City Royals to their first Pennant in 1980, and the Chicago Cubs to their first Division Title in 1984, with his classmate Zim as a coach.

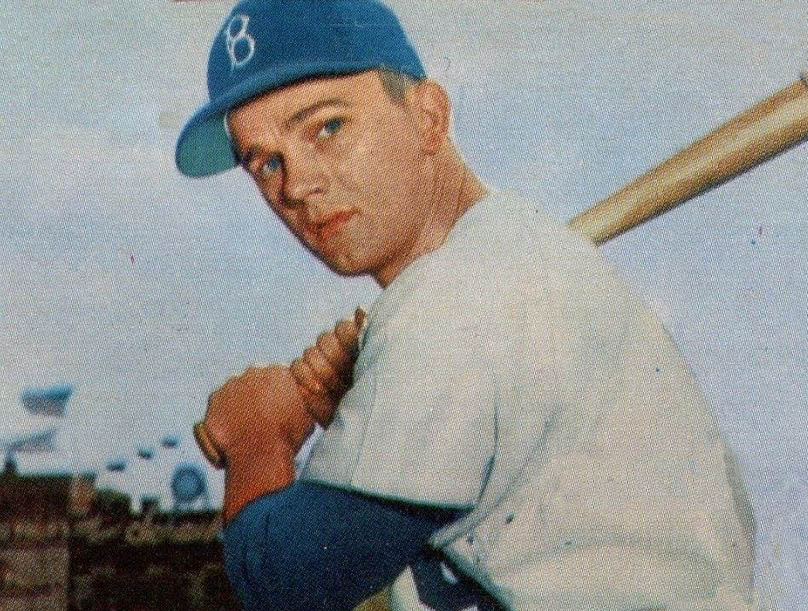

He signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1949, and his first club was the Cambridge Dodgers, in the Eastern Shore League in Maryland -- then called Class D, the equivalent of what we now call "short-season A ball." Joe Pignatano was a teammate, and would have a very similar career, being with Zim on the last Brooklyn team in 1957 and the first Met team in 1962, and have a long career as a coach; he is still alive.

In 1951, Zim was playing with the Elmira Pioneers of the New York-Penn League. (Formerly the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York, or "PONY League.") Before a game there that season, he married his high school girlfriend, Carol Jean Bauerle, a.k.a. "Soot." They would remain together for 63 years, settling in the Tampa Bay area in the late 1950s, so they were there long before they got old, or before the area, or Florida in general, became known as a haven for old people. They would have a son Thomas (now a scout for the San Francisco Giants) and a daughter Donna, with 4 grandchildren, including Beau Zimmer, now a reporter for WSTP-Channel 10 in St. Petersburg.

In 1953, he was playing for the St. Paul Saints of the American Association, and was hit in the head with a pitch. The pitcher's name was Jim Kirk -- no relation to the Star Trek captain of the same name. As far as anybody's ever been able to determine, it was not on purpose. But that didn't really matter, as Zim lost consciousness for 13 days and nearly died at age 22.

This produced the legend that Zim had "a steel plate in his head." This wasn't true, but doctors did drill holes in his skull, to relieve the pressure of swelling. It took some time for his vision to clear, and for him to relearn how to walk and talk. After this beaning, the Dodger brass made batting helmets mandatory throughout their organization. Soon, it became an universal rule, after having been optional beforehand.

He was called up by the Dodgers, and played his first major league game, wearing Number 23, on July 2, 1954. It was against the Philadelphia Phillies, at Connie Mack Stadium. In his first at-bat, in the top of the 3rd, Zim hit a triple down the left-field line off Curt Simmons, and scored on a single by Don Hoak. In the top of the 5th, he drew a walk on Simmons. In the top of the 6th, after reliever Steve Ridzik gave up a home run to Roy Campanella, Zim struck out against him. Billy Cox also homered for the Dodgers, Del Ennis for the Phillies. The Phillies won, 7-6, as the Dodgers blew leads of 2-0, 4-1 and 5-4. Ridzik won it, Clem Labine lost it, both in relief. Robin Roberts, one of the best starting pitchers of the era, got the save.

Here's what Major League Baseball was like back when Zim made his debut. A few teams, including the Yankees, had still not fielded a black player. Hispanic players were even rarer. Asian players, forget it. No artificial turf, no domes, no designated hitter, no interleague play. Only 15 years earlier, lights were rare. There were electric scoreboards, but not electronic ones, no big TV screens on them, no boards or roof apparati shooting off fireworks. As I said, batting helmets were then a choice. Only recently had fielders stopped leaving their gloves on the field after an inning. The Boston Braves had just moved to Milwaukee, and the St. Louis Browns had just moved to become the Baltimore Orioles. There were American League teams in Philadelphia and Washington, a National League team in Brooklyn, no teams south of Washington, Cincinnati or St. Louis, and no teams west of St. Louis. No team in Canada. Kansas City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Minneapolis, St. Paul, Houston, Atlanta, Oakland, San Diego, Montreal, Seattle, Dallas, Fort Worth, Toronto, Denver, Miami, Tampa, St. Petersburg and Phoenix... these 20 cities were then represented by 21 minor-league teams. Now, they are represented by 17 major-league teams. Honus Wagner, Nap Lajoie, Cy Young, and Hugh Duffy, the best hitter of the 1890s, were still alive.

The Dodgers ran away with the NL Pennant in 1955, with Zim alternating between 2nd base, shortstop, 3rd base and left field. The World Series against the Yankees went to Game 7. In the bottom of the 6th, with the Dodgers clinging to a 2-0 lead, manager Walter Alston removed Zim from the game, moved Jim Gilliam from left field to take his place at 2nd base, and moved Sandy Amoros to left field. This proved to be brilliantly timed, as the Yankees launched a rally, and Yogi Berra, who rarely hit to the opposite field, did just that. Had the righthanded Gilliam, with not much speed and his glove on his left hand, still been in left field, the ball would have dropped into the corner for at least a double, and the Yankees would have tied the game. Instead, it was the lefthanded Amoros out there, and he snared the ball with his glove on his right hand, and fired back to the infield to finish a rally-killing double play.

With Johnny Podres pitching superbly, the Dodgers hung onto that 2-0 lead, and won their first World Series. With Zim's death, there is now only one living Dodger who played in that game, 59 years ago: George Shuba, whom Alston had sent up to pinch-hit for Zim. With the recent death of Jerry Coleman, the only remaining Yankees in the game are Yogi and Bob Cerv. (Whitey Ford is still alive, but did not appear in the game.) There are 6 living men who played for the Dodgers in 1955: "Shotgun" Shuba, Carl Erskine, Roger Craig, Ed Roebuck, Sandy Koufax and Tommy Lasorda. (Yes, that Lasorda.)

The Dodgers won the Pennant again in 1956, but this time, the Yankees won, including in Game 5, with Don Larsen pitching a perfect game, still the only no-hitter in World Series history and one of only 2 no-hitters ever thrown in postseason play. Zim did not appear in that game, but he was in the Dodger dugout. The only living players remaining are Larsen and Yogi, although, again, Ford was on hand but not in the game.

Zim was the Dodgers' shortstop in their last home game in Brooklyn, at Ebbets Field on September 24, 1957, a 2-0 win over the Pittsburgh Pirates, with Danny McDevitt pitching a shutout. He got the last hit in the ballpark, a single to center in the 7th. The Dodgers moved to Los Angeles for 1958, and their arch-rivals, the New York Giants, to San Francisco at the same time. Zim did not however, play in the Dodgers' first game in L.A., on April 18, a 6-5 win over the Giants at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. But he did play for them in the 1959 World Series, and helped them win the first World Championship won by a baseball team west of St. Louis.

In 1960, he was traded to the Chicago Cubs, and would be with them in the 2 seasons in which they employed their "College of Coaches," a system that seemed to make sense on paper, with managers moving up through the minor leagues with the players they'd managed. That is frequently done today. The problem was, the Cubs took it too far, and rotated the managers among the permanent coaching staff during the season. Each new manager had a different style and different strategies, with no single guide (as in "Joe Girardi's Binder") to keep things consistent. Whatever Zim learned about managing, his experience playing at Wrigley Field sure taught him now not to manage a big-league ballclub.

After the 1961 season, in which he'd made the All-Star Team for the first and only time, the Cubs traded him to the expansion New York Mets. In the club's first-ever game, at Sportsman's Park (by then renamed to be the first Busch Stadium) on April 11, 1962, he played 3rd base, batted 7th, and went 1-for-4. In spite of home runs by Gil Hodges and Charlie Neal, the Mets lost to the St. Louis Cardinals, 11-4. Two days later, the Mets played their first home game, and Zim was one of 4 Mets photographed and filmed jumping in front of the center field clubhouse. Again, he played 3rd base, batted 7th, and went 1-for-4. Again, the Mets lost, 4-3 to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

On May 7, he was relieved from having to play for "the worst team in baseball history," traded to his hometown Reds for Cliff Cook and one of the 2 Bob Millers who would end up pitching for the '62 Mets, and rooming together. (The early Mets tended to not think things through. Worse than now.) It would be a short return to the Queen City of the Midwest, and he would spend his last 3 major league seasons with the Washington Senators. He would play for the Toei Flyers in Japan in 1966, and in 1967 closed his playing career by returning to the Reds as a player-manager in the minors, first with the Double-A Knoxville Smokies, then with the Triple-A Buffalo Bisons.

He also played in the Latin American winter leagues, in Cuba, Mexico and Puerto Rico. In Cuba, he was known as "El Galleguito" (The Gallegan). In Mexico and Puerto Rico, "El Soldadito" (The Small Soldier).

His playing career was more remarkable for what he had seen than for what he had done. He batted just .235, with a 77 career OPS+ -- meaning he was 23 percent less productive than the average hitter of his time. He collected just 773 hits and 91 home runs in his 12 big-league seasons. His best year was probably 1958, the first season in Los Angeles: He batted .262, and the weird setup at the Coliseum allowed him to reach career highs with 17 homers and 60 RBIs. He also had a career-high 14 stolen bases, although the high, close left-field screen, the "Chinese Wall," would have had nothing to do with that.

*

At the age of 36, his playing career was over. But his life in baseball was just getting warmed up. In 1968, he managed the Reds' Triple-A club again, this time the Indianapolis Indians. In 1969, the expansion San Diego Padres snapped him up, and he managed in Key West that year and in Salt Lake City the next. He was the Montreal Expos' 3rd base coach in 1971, and the Padres brought him back to the same post in 1972. Just 11 games into the season, the Padres fired Preston Gomez, and Zim was a big-league manager for the first time, at age 41.

It didn't last long, and the Padres were bankrupt, nearly moving to Washington, D.C. for the 1974 season. Zim was fired before that season could begin, but the Boston Red Sox made him their 3rd base coach. Zim was there for the 1975 World Series against his hometown Reds, for all the great and odd things that happened in that Series, from Luis Tiant's shutout and game-winning hit to the Ed Armbrister "interference" play, to Bill Lee's eephus pitch knocked out by Tony Perez to Joe Morgan's last-game, last-inning winning blooper. When Carlton Fisk did the Fenway Twist with that walkoff home run in Game 6, it was Zim who slapped him on the back as he rounded 3rd and the fans poured onto the field.

But in a real "What have you done for me lately" move, the Red Sox fired their Pennant-winning manager, Darrell Johnson, the next year. (It might not have been a bad move: He soon became the first manager of the expansion Seattle Mariners, and didn't seem to have a clue, and never managed again.) Zim became the Sox' manager, and after a rough start under Johnson, he got them to recover to win 83 games. In each of the next 3 full seasons, they won 97, 99 and 91 games. Sounds like Zim was a good manager.

There was a problem, though. In 1976, '77 and '78, the Yankees were better, winning 96, 100 and 100. In 1979, the Baltimore Orioles were better, winning 102. The Sox won nothing while Zim was their manager, and late in the 1980 season, he was fired.

Those are the facts that show up in a plain, colorless record on a sheet of paper or on a computer screen. They do not tell the full story. As with the Yankees of the same period, so much has been written about the Red Sox of the late 1970s, and it tends to defy belief. Lord Byron was right: Truth truly is stranger than fiction.

Yes, the Red Sox had Hall-of-Famers Carl Yastrzemski, Jim Rice and Carlton Fisk, and Fred Lynn, who might have been one if he hadn't gotten hurt. But they also had a bunch of characters on that team. When Tiant did goofy things, it was tolerated because he backed it up with great pitching. But then, there was a subset of the team, led by Lee, guys whose mouths and hijinks did more talking than their on-field performance.

Pitcher Ferguson Jenkins, himself a Hall-of-Famer but underachieving in Boston, told a reporter, "I look at him like I look at the buffalo, the stupidest animal that ever was." Lee ran with that, and called their gang "the Buffalo Heads." He also called Zim "the Gerbil," a nickname that stuck with him for a long time. (He was also called "Popeye," due to his resemblance to the cartoon character.)

After the Sox led most of the '77 season, but got beat out by the Yankees, he had enough: He blamed the Buffalo Heads, thinking their fooling around was hurting their performance and thus the team, and got general manager Haywood Sullivan to break them up. This may not have been a good idea: Jenkins was traded to the Texas Rangers, and his career was reborn; while Bernie Carbo was sold to the Cleveland Indians. And Zimmer banished Lee to the bullpen.

The Red Sox were in 1st place by 9 1/2 games on July 18, 1978, 14 games ahead of the Yankees. But injuries and a Yankee surge did them in. In early September, the Yankees had closed to within 4 games, and then swept a 4-game series at Fenway Park to tie for 1st, winning 15-3, 13-2, 7-0 and 7-4. The Sox started Jim Wright in the 2nd game and Bobby Sprowl in the 4th, both rookies who never did much. Legend has it that Yaz himself went to Zim before the 4th game, and begged him to start Lee, but Zim responded by reminding Yaz of all the rotten things Lee had said about him. The legend also says that Carbo would have been a big help down the stretch.

Anybody who tells you this version of the story, and only this version, is dishonest. Jenkins and Carbo both had cocaine problems, which they would later overcome. Jenkins did so in time to salvage his career; Carbo did not, and his life disintegrated, before former Sox teammate Dalton Jones brought him to evangelical Christianity and rehab. He became a hairdresser and a minister (How's that for a combination?), and, like Jenkins, is doing just fine today.

As for Lee, Zimmer did not refuse to pitch him during that series. Indeed, he used Lee in relief in both the 2nd game and the 4th. He pitched decently both times, but it was too late.

The truth is that Lee was in Zim's doghouse because Lee simply wasn't getting the job done. He had lost his last 7 starts. True, the Sox had injury issues, and were held to 3 runs or less in 4 of the 7. But in 4 of the 7, Lee didn't last 6 innings; he got knocked out in the 1st in one and the 4th in another. His ERA over that stretch was 5.18. If "Spaceman" Lee wants to blame somebody for the Red Sox' 1978 choke, there's plenty of blame to go around, and he can start by looking in the mirror.

In an interview for the NBC Game of the Week in the Yanks-Sox series at Yankee Stadium the week after the "Boston Massacre" series, Zimmer said, "'Choke' is not in my vocabulary. 'Slump' is." The Sox would drop the first 2 games of that series as well, falling 3 1/2 games behind the Yankees, before salvaging the last game, then winning 10 of their last 12, including their last 8, to forge a tie for 1st and force a Playoff to decide the AL Eastern Division title.

In today's baseball, Zimmer would probably have taken out Mike Torrez after pitching 6 innings of 2-hit shutout ball. At the very least, he would have taken him out after allowing 2 baserunners in the 7th. If he had done that, and Bucky Dent had hit that home run off Bob Stanley instead, Zim would have been roasted by the New England media and "Red Sox Nation" for that.

But the guy won 287 games in 3 full seasons. How bad a manager could he have been? Or, to put it another way: The Sox traded Lee after the 1978 season, to the Montreal Expos, for Stan Papi, who turned out not to be a "Big Papi." Lee, on the other hand, won 16 games for the Expos in 1979, his career revitalized by the looser atmosphere of Montreal and being away from Zimmer. But that was a last gasp, and 3 years later, only 35, he was done. What does that say about Lee that he was a lefthanded pitcher, but after age 35 nobody wanted him?

When Zimmer wrote his memoir Zim: A Baseball Life, he addressed the feud with Lee, pointing out that Lee wasn't pitching well, and that it was totally a baseball decision, not a personality decision. He did, however, also say that Lee was the only player he had ever managed whom he would not invite into his house. He didn't say that about any of the other Buffalo Heads: Just Lee.

*

Zim's baseball life continued long after leaving Boston. For 2 seasons, he managed the Texas Rangers without success. In 1983, the Yankees, of all teams, hired him as a coach. He was told that Dent, no longer a Yankee, was renting his Bergen County, New Jersey house out, and Zim rented it. He said it was a good house, but the only problem was that, in every room, there was a picture of Dent hitting that home run, or being greeted at home plate afterward. Zim said he had to take all those pictures down!

In 1984, the aforementioned Jim Frey hired Zim as a Cub coach, and the team reached the postseason for the first time in 39 years. But the Steve Garvey home run in Game 4 and the Leon Durham error in Game 5 doomed them, and the Cubs lost to the San Diego Padres. Late in 1987, Frey was fired, and Zim was promoted. In 1989, he led the Cubs to another NL East title, proving his point that he was a good manager. However, they lost the NL Championship Series to the Giants. No choke, no weird occurrence, they just got beat by a better team.

Those are the facts that show up in a plain, colorless record on a sheet of paper or on a computer screen. They do not tell the full story. As with the Yankees of the same period, so much has been written about the Red Sox of the late 1970s, and it tends to defy belief. Lord Byron was right: Truth truly is stranger than fiction.

Yes, the Red Sox had Hall-of-Famers Carl Yastrzemski, Jim Rice and Carlton Fisk, and Fred Lynn, who might have been one if he hadn't gotten hurt. But they also had a bunch of characters on that team. When Tiant did goofy things, it was tolerated because he backed it up with great pitching. But then, there was a subset of the team, led by Lee, guys whose mouths and hijinks did more talking than their on-field performance.

Pitcher Ferguson Jenkins, himself a Hall-of-Famer but underachieving in Boston, told a reporter, "I look at him like I look at the buffalo, the stupidest animal that ever was." Lee ran with that, and called their gang "the Buffalo Heads." He also called Zim "the Gerbil," a nickname that stuck with him for a long time. (He was also called "Popeye," due to his resemblance to the cartoon character.)

After the Sox led most of the '77 season, but got beat out by the Yankees, he had enough: He blamed the Buffalo Heads, thinking their fooling around was hurting their performance and thus the team, and got general manager Haywood Sullivan to break them up. This may not have been a good idea: Jenkins was traded to the Texas Rangers, and his career was reborn; while Bernie Carbo was sold to the Cleveland Indians. And Zimmer banished Lee to the bullpen.

The Red Sox were in 1st place by 9 1/2 games on July 18, 1978, 14 games ahead of the Yankees. But injuries and a Yankee surge did them in. In early September, the Yankees had closed to within 4 games, and then swept a 4-game series at Fenway Park to tie for 1st, winning 15-3, 13-2, 7-0 and 7-4. The Sox started Jim Wright in the 2nd game and Bobby Sprowl in the 4th, both rookies who never did much. Legend has it that Yaz himself went to Zim before the 4th game, and begged him to start Lee, but Zim responded by reminding Yaz of all the rotten things Lee had said about him. The legend also says that Carbo would have been a big help down the stretch.

Anybody who tells you this version of the story, and only this version, is dishonest. Jenkins and Carbo both had cocaine problems, which they would later overcome. Jenkins did so in time to salvage his career; Carbo did not, and his life disintegrated, before former Sox teammate Dalton Jones brought him to evangelical Christianity and rehab. He became a hairdresser and a minister (How's that for a combination?), and, like Jenkins, is doing just fine today.

As for Lee, Zimmer did not refuse to pitch him during that series. Indeed, he used Lee in relief in both the 2nd game and the 4th. He pitched decently both times, but it was too late.

The truth is that Lee was in Zim's doghouse because Lee simply wasn't getting the job done. He had lost his last 7 starts. True, the Sox had injury issues, and were held to 3 runs or less in 4 of the 7. But in 4 of the 7, Lee didn't last 6 innings; he got knocked out in the 1st in one and the 4th in another. His ERA over that stretch was 5.18. If "Spaceman" Lee wants to blame somebody for the Red Sox' 1978 choke, there's plenty of blame to go around, and he can start by looking in the mirror.

In an interview for the NBC Game of the Week in the Yanks-Sox series at Yankee Stadium the week after the "Boston Massacre" series, Zimmer said, "'Choke' is not in my vocabulary. 'Slump' is." The Sox would drop the first 2 games of that series as well, falling 3 1/2 games behind the Yankees, before salvaging the last game, then winning 10 of their last 12, including their last 8, to forge a tie for 1st and force a Playoff to decide the AL Eastern Division title.

In today's baseball, Zimmer would probably have taken out Mike Torrez after pitching 6 innings of 2-hit shutout ball. At the very least, he would have taken him out after allowing 2 baserunners in the 7th. If he had done that, and Bucky Dent had hit that home run off Bob Stanley instead, Zim would have been roasted by the New England media and "Red Sox Nation" for that.

But the guy won 287 games in 3 full seasons. How bad a manager could he have been? Or, to put it another way: The Sox traded Lee after the 1978 season, to the Montreal Expos, for Stan Papi, who turned out not to be a "Big Papi." Lee, on the other hand, won 16 games for the Expos in 1979, his career revitalized by the looser atmosphere of Montreal and being away from Zimmer. But that was a last gasp, and 3 years later, only 35, he was done. What does that say about Lee that he was a lefthanded pitcher, but after age 35 nobody wanted him?

When Zimmer wrote his memoir Zim: A Baseball Life, he addressed the feud with Lee, pointing out that Lee wasn't pitching well, and that it was totally a baseball decision, not a personality decision. He did, however, also say that Lee was the only player he had ever managed whom he would not invite into his house. He didn't say that about any of the other Buffalo Heads: Just Lee.

*

Zim's baseball life continued long after leaving Boston. For 2 seasons, he managed the Texas Rangers without success. In 1983, the Yankees, of all teams, hired him as a coach. He was told that Dent, no longer a Yankee, was renting his Bergen County, New Jersey house out, and Zim rented it. He said it was a good house, but the only problem was that, in every room, there was a picture of Dent hitting that home run, or being greeted at home plate afterward. Zim said he had to take all those pictures down!

In 1984, the aforementioned Jim Frey hired Zim as a Cub coach, and the team reached the postseason for the first time in 39 years. But the Steve Garvey home run in Game 4 and the Leon Durham error in Game 5 doomed them, and the Cubs lost to the San Diego Padres. Late in 1987, Frey was fired, and Zim was promoted. In 1989, he led the Cubs to another NL East title, proving his point that he was a good manager. However, they lost the NL Championship Series to the Giants. No choke, no weird occurrence, they just got beat by a better team.

Fired by the Cubs after the 1991 season, he returned to the Red Sox as a coach in 1992, under his former player Butch Hobson. In 1993, he was in uniform for an expansion team for the 3rd time, with the Colorado Rockies. He was with them for the first major league game ever played in the Mountain Time Zone, which was also the largest Opening Day crowd ever, 80,227, as the Rockies beat the Montreal Expos at Mile High Stadium. He was there as the Rockies set attendance records for most fans in a season (1993) and most fans per home game (1994 before the strike began, preventing them from breaking the previous season's record for most total fans). And he was with them as they reached the Playoffs for the first time, winning the 1995 NL Wild Card.

In 1996, Joe Torre became Yankee manager, and asked Zim to be his bench coach. The two men had no previous connection, but Torre knew a "baseball lifer" when he saw one, and their partnership became legendary as the Yankees, in the next 8 seasons, made the Playoffs every year, won 6 Pennants and 4 World Championships. Nearly every camera shot of Torre in the dugout had Zimmer on one side of him, and pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre on the other.

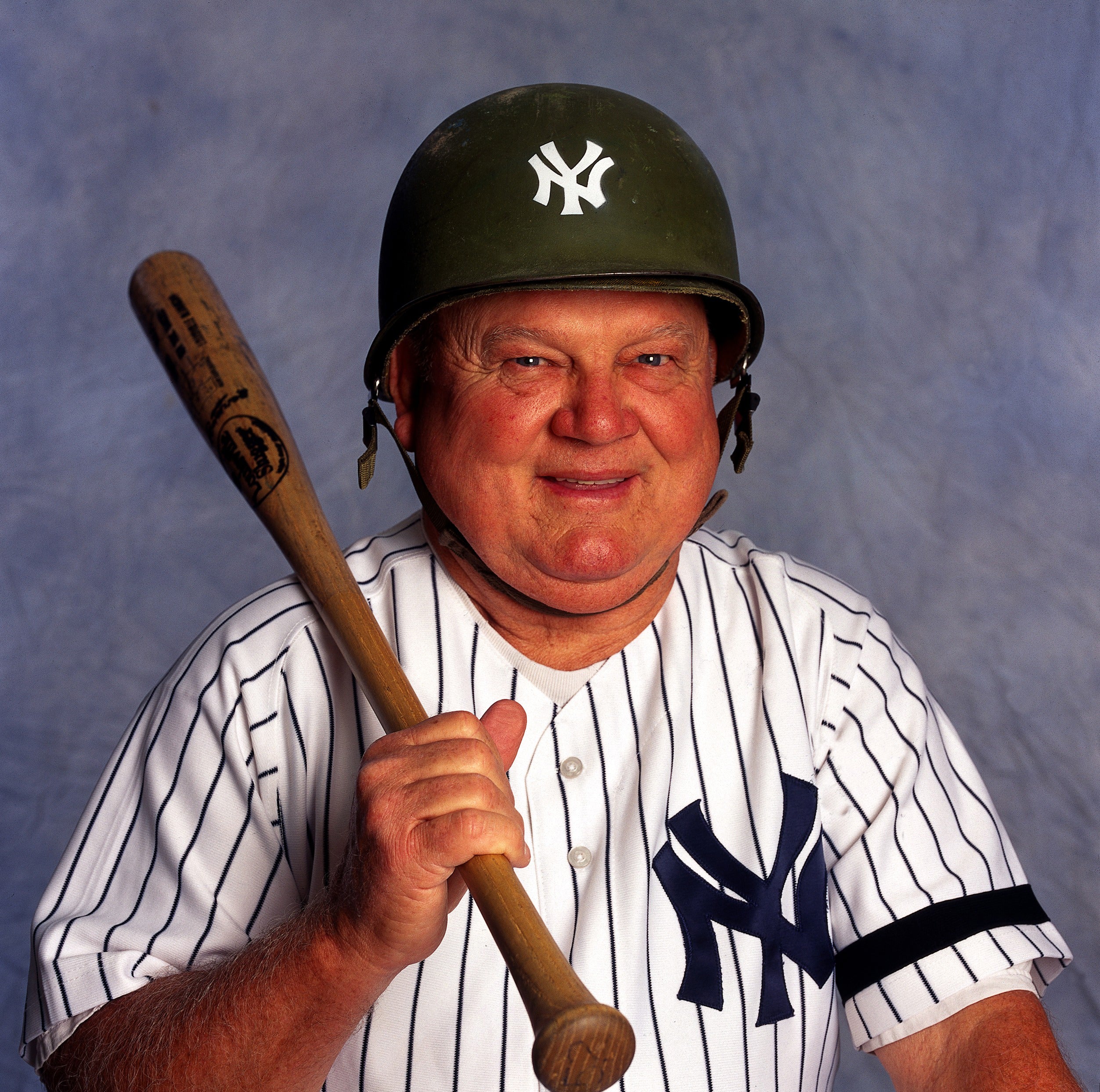

In the 1998 AL Championship Series, Zim was struck on his big bald head by a line drive. The next night, he showed up in the dugout wearing an Army helmet with an NY logo on it. The following season, he subbed as manager while Torre was being treated for prostate cancer, and went a decent 21-15 in his last (if unofficial) big-league managing job.

In 1996, Joe Torre became Yankee manager, and asked Zim to be his bench coach. The two men had no previous connection, but Torre knew a "baseball lifer" when he saw one, and their partnership became legendary as the Yankees, in the next 8 seasons, made the Playoffs every year, won 6 Pennants and 4 World Championships. Nearly every camera shot of Torre in the dugout had Zimmer on one side of him, and pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre on the other.

In the 1998 AL Championship Series, Zim was struck on his big bald head by a line drive. The next night, he showed up in the dugout wearing an Army helmet with an NY logo on it. The following season, he subbed as manager while Torre was being treated for prostate cancer, and went a decent 21-15 in his last (if unofficial) big-league managing job.

October 11, 2003. Game 3 of the ALCS. Fenway Park, where Zim was still not forgiven by a big chunk of the Red Sox fan base. Pedro Martinez had been hitting Yankee batters on purpose ever since he arrived in Boston, and hit Karim Garcia in the back. There was yelling back and forth. Jorge Posada yelled at Pedro in Spanish, to make sure he understood perfectly. Pedro pointed at his head, and then at Jorge, as if to say, "Look, pal, if you wanna be next, I can arrange it."

Later, Roger Clemens threw head-high -- but over the plate -- to Manny Ramirez, and Manny pointed to Clemens, and charged the mound with his bat. All hell broke loose. Zimmer, remembering his beaning -- actually, he'd been beaned a 2nd time before reaching the majors, but that one wasn't nearly as serious -- ran after Pedro.

At the time, Pedro Martinez was approaching his 32nd birthday, and was lean and strong; while Don Zimer was 72, fat and slow, and probably not a threat to anyone. Instead of just putting his hands up to stop Zim, Pedro grabbed him by the head and threw him to the ground. Luckily, Zim only sustained a cut to his head. Both men apologized for their actions. But I already had contempt for Pedro, and this made him the most hated opponent of any of my teams. Even in what turned out to be his last game in the majors, Game 6 of the 2009 World Series for the Phillies against the Yankees, Yankee Fans, instead of showing respect to a pitcher who will probably get into the Hall of Fame, booed the hell out of him.

The Yankees would go on to win that Pennant against the Sox, highlighted by a late Game 7 collapse that would lead to Sox fans adding Grady Little to the list of Sox managers they hated, followed by the winning homer of Aaron Boone. But they lost the World Series to the Florida Marlins.

Afterward, Zim and Yankee owner George Steinbrenner got into an argument, and Zim decided he'd had enough of The Boss. He decided that enough was enough, and, after an adult life in which he was proud to say he'd never picked up a paycheck from anything except baseball, went back to Tampa Bay and Soot, and retired from baseball.

But the Tampa Bay Devil Rays (just "Rays" from 2008 onward) made him an offer he couldn't refuse: Bench coach, home games only, no travel, and spring training instructor (also no travel). He took the job, and increased his uniform number by 1 every year, to match the number of years he'd been involved in professional baseball. In spring training 2014, he wore Number 66.

He was involved with the Rays as they went from a joke franchise to a perennial contender, reaching the Playoffs for the first time in 2008, winning the Pennant, and, albeit in a limited role, being to manager Joe Maddon what he had been to Joe Torre.

It's worth noting that Joe Torre managed a Major League Baseball team in baseball in 29 seasons. In 8 seasons with Don Zimmer beside him, he won 6 Pennants. In 21 seasons without Zim, he won exactly none -- even with such good teams as the 1982 Atlanta Braves, the 1993 St. Louis Cardinals, the 2006 New York Yankees and the 2009 Los Angeles Dodgers. In contrast, while Zim never won a Pennant as a manager without Torre, he did win a Division title without him.

*

Between playing, coaching, and managing, Don Zimmer reached postseason play 20 times (19 if you don't count the Bucky Dent Game), winning 11 Pennants and 6 World Championships. He got started as a professional in the second term of President Harry Truman, in the era of black & white TV, when some stars of the silent screen (1927 and earlier) were still acting; and ended in the second term of President Barack Obama and the age of social media, and having gone from when "starlet" meant Lauren Bacall to when it meant Jennifer Lawrence.

Somebody once called Zim "the Forrest Gump of baseball," for having been there, if not necessarily an integral part of it, for so much of baseball history. That may not be fair -- Forrest was developmentally disabled, and Zim certainly wasn't dumb, contrary to what Fergie Jenkins and Bill Lee said -- but if we accept "the beginning of professional baseball" as being the establishment of the Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1869, then he was involved with pro baseball for 45 percent of its entire history. He saw all there was to see in his time, from playing alongside Jackie Robinson in 1954 to coaching against Mike Trout in 2014.

He'd been suffering from heart and kidney problems, and died yesterday, at the age of 83. Death was the only thing that could truly keep Don Zimmer out of baseball.

But guys like that never truly leave the game. As Thomas Boswell, the great baseball columnist of The Washington Post, once put it, "We live in a disposable society. But we don't dispose of Babe Ruth. We don't dispose of Walter Johnson. We speak of these men as family, and as contemporaries, though they are dead."

Many people -- players, managers, general managers, owners, umpires, sportswriters, fans -- would have liked to have disposed of Don Zimmer. Some actually tried. Even death will not fully succeed. He's a baseball man forever.

UPDATE; Don was cremated, so there is no gravesite.

No comments:

Post a Comment