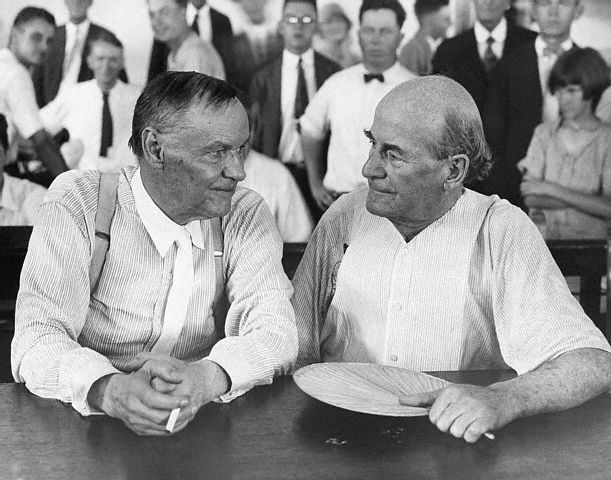

Clarence Darrow (left) and William Jennings Bryan

July 21, 1925, 100 years ago: A verdict is reached in the trial of The State of Tennessee vs. John Thomas Scopes, what has gone down in history as "The Scopes Monkey Trial."

Four months earlier, the Tennessee legislature passed the Butler Act, a law banning the teaching of evolution in its public schools, following news reports of children coming home from school and telling their parents, "The Bible is all nonsense." The law was named for its sponsor, State Representative John Washington Butler, who was also the head of the World Christian Fundamentals Association.

The American Civil Liberties Union chose to challenge this law. They found John Scopes, a 24-year-old Kentucky native who was teaching science and coaching football at Rhea County High School in Dayton, Tennessee, about 40 miles north of Chattanooga. Since the only penalty for teaching evolution in a public school in the State was a fine of $100 -- about $1,816 in today's money -- and he wouldn't be sent to prison, Scopes agreed to do it. On May 5, 1925, he was charged with violating the law.

Tom Stewart, a future U.S. Senator, was the lead prosecutor. Joining the prosecution team was William Jennings Bryan. The former Congressman from Nebraska had been nominated for President by the Democratic Party in 1896, 1900 and 1908, losing by a wider margin each time. He had served as Secretary of State in the 1st 2 years of Woodrow Wilson's Presidency, 1913-15.

In spite of an overall record that was very liberal for the time, he was a fundamentalist Presbyterian, and enthusiastically supported the law. His only misgiving was the fact that he hadn't tried a case in 36 years.

The ACLU needed a defense attorney. They wrote to H.G. Wells, the great science fiction writer, and a known Socialist and atheist. He wrote back and declined, saying that he had no legal training in his native Britain, let alone in America. John R. Neal, a professor at the University of Tennessee School of Law in Knoxville, volunteered.

But the ACLU thought he wasn't enough. So they called upon the foremost defense attorney of the day, Clarence Darrow. A year earlier, Darrow, a Chicago-based agnostic, had managed to save "thrill killers" Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb from the death penalty for their brutal kidnapping and murder of a 14-year-old boy. The ACLU believed that, if he could argue effectively that the death penalty was wrong, they could argue that the law banning the teaching of evolution was wrong -- and that, while they were unlikely to win this case, they could later get the law overturned as unconstitutional.

Darrow was a brilliant man. At first, he turned them down, knowing that the Leopold-Loeb trial had become a media circus, and he didn't want the same thing to happen here. They talked him into realizing that this was a ship that had already sailed. The proceedings would be broadcast nationally on the new medium of radio.

Journalists had come from all over the world, including H.L. Mencken, the nationally-syndicated columnist from The Baltimore Sun, who had agreed to pay Scopes' legal fees. (But not his fine.) On the other hand, he had called the defendant "the infidel Scopes" in his column, and had also given the case the name it has had ever since: "The Monkey Trial."

Bryan, the foremost political speechmaker of his era -- an era that had certainly passed by this point -- decided to go with the circus atmosphere, as it suited his style. He mocked evolution as a theory, for teaching that humans were descended "not even from American monkeys, but from Old World monkeys."

As with the murderous Leopold and Loeb, Darrow knew that the nonviolent Scopes had, beyond any question, committed the crime for which he was charged. He knew there was no hope of winning the case -- in this round. But he understood the possibility of getting the Butler Act overturned as unconstitutional by a higher court.

So he went after it on that ground: He said that the Bible should be preserved in the realm of theology and morality, and not put into a course of science. Then he took the dramatic turn of attacking his opponent: He said that Bryan was waging "a duel to the death against evolution," and said, "There is never a duel with the truth."

On the 7th day of the trial, the Judge, John T. Raulston, ordered the proceedings moved to the lawn of the Rhea County Courthouse, because it was simply too hot inside: Air conditioning was still rare. On that day, Darrow took a truly radical step: He called Bryan, his opponent, to the stand, as "an expert on the Bible." Bryan made a key mistake: He accepted, mainly because his ego had been bruised by Darrow's previous speech.

Darrow asked Bryan about some of the more fantastical stories in the Bible: Whether Eve was created from one of Adam's ribs, how their son Cain could have found a wife if Eve was still the only woman on Earth (Bryan: "I will leave the agnostics to hunt for her"), whether Joshua could make the Sun stand still in the sky, and so forth.

In 1955, Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee wrote the play Inherit the Wind. Unfortunately, the best line from the play appears to have been made up for it, and didn't happen in real life. The Darrow character, named Henry Drummond, holds a rock, and asks the Bryan character, named Matthew Brady, how old the rock is. Brady says, "I am more interested in the Rock of Ages than in the age of rocks."

In the play, Brady sticks to the "Biblical chronology" of the Irish archbishop James Ussher, who published a paper in 1654 stating that the Creation told in The Book of Genesis occurred in 4004 BC. Drummond said that the rock in question was not 6,000 years old, but millions of years old. (For comparison's sake: Ussher said that Noah's Flood happened in 2348 BC, the Exodus in 1446 BC, and the death of King David and the accession of his son King Solomon in 970 BC. The most common date given for the destruction of Troy in the Trojan War is 1275 BC, and the founding of Rome is said to have been in 753 BC.)

After 2 hours of testimony, Bryan was looking forward to cross-examining Darrow, which, under most circumstances, he would have had the right to do. But Judge Raulston ruled that all the arguments against the Bible were immaterial to the case, and therefore irrelevant. He was right: Nothing that Darrow alleged in his statements and questions addressed the trial's central fact, which was whether or not Scopes broke the law as it then stood. The law's fairness was not at issue in the trial.

Bryan was furious: He had been denied his chance to make the speech of his life, surpassing even his pro-free silver "Cross of Gold" speech at the 1896 Democratic Convention in Chicago. Like so many old people -- he was now 65 -- he recognized that he had far more yesterdays than tomorrows, and was thinking more about death, and clinging more toward the hope that his religion gave him for an afterlife. As a result, he was now sounding more an more like a modern-day evangelical Republican than as the intellectual founding father of the modern Democratic Party, as he sometimes seems to be.

The trial took 8 days. The jury's deliberations took 9 minutes. They found Scopes guilty. Raulston ordered the $100 fine paid. He could have set the sentence aside, but ordered it. Once he did, Scopes, who did not testify on his own behalf, spoke for the only time in the proceedings:

Nonetheless, the fine was levied. The ACLU, as they promised, paid it.

Over the next 5 days, Bryan delivered some speeches in Tennessee. But on July 26, 1925, he had a stroke, and died at his hotel in Dayton. Most people, at the time, thought that the trial had a deleterious effect on his health, although this was not proven, since there was no autopsy. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington.

Darrow continued to practice law in Chicago until 1938, when he died of heart disease at age 80. Judge Raulston wanted to increase his political profile with the case, but was defeated for re-election in 1927. Representative Butler was also defeated for re-election in 1927. Neither ever won another office: Raulston ran for Governor and lost. He finally admitted that he no longer believed that the State should pass laws like the Butler Act. Butler died in 1952, Raulston in 1956.

Scopes lost his teaching career in the Great Depression, and he, his wife and 2 sons had to move in with his parents in Paducah. He entered politics, and ran for the State House of Representatives in 1932, as a Socialist, and lost. Then he did something very un-socialist: Having gotten a master's degree in geology, he worked for an energy company that would later be bought out by Pennzoil, in Houston and later in Shreveport, Louisiana.

On October 10, 1960, he and two men claiming to be him were guests on the TV game show To Tell the Truth. Scopes was an ideal subject for that show: Since his fame came before the age of television, his name was well-known, but his face wasn't.

In 1967, Gary Scott, a science teacher in Jacksboro, Tennessee, was fired for teaching evolution. He sued, following Darrow's idea that the law itself should one day be challenged as unconstitutional, and said that forbidding its teaching was a violation of the 1st Amendment's protection of speech. The school board got scared, and reinstated him. He didn't care: He went forward with his suit. Three days later, on May 18, 1967, 42 years after the Scopes Trial, the State legislature passed a law repealing the Butler Act. The same day, Governor Buford Ellington signed it into law. Scott dropped his suit.

Scopes' thoughts on the repeal are not recorded: He wrote a memoir, but it wasn't published until a few days after the repeal. He died of cancer in Shreveport in 1970, at 70.

As I mentioned, in 1955, the play Inherit the Wind was written, using a fictionalized version of the Scopes Trial as a critique of McCarthyism. Ironically, the title comes from the Bible: Proverbs 11:29 reads, "He that troubleth his own house shall inherit the wind, and the fool shall be servant to the wise of heart."

When it was first staged on Broadway, Darrow/Drummond was played by Paul Muni, and Bryan/Brady by Ed Begley Sr. A young Tony Randall was also in the cast. It was filmed in 1960 with Spencer Tracy and Fredric March. It was adapted for television in 1965, with Melvyn Douglas and Begley. (As far as I know, his son, Ed Begley Jr., has never appeared in a version of the play.) A 1988 TV-movie had Jason Robards and Kirk Douglas. A 1996 Broadway revival had George C. Scott and Charles Durning. A 1999 TV-movie had Scott switching roles to play Bryan/Brady, and Jack Lemmon as Darrow/Drummond. A 2007 Broadway revival had Christopher Plummer and Brian Dennehy.

No comments:

Post a Comment