January 12, 1975, 50 years ago: Western Pennsylvania, and Pittsburgh in particular, has long been known as a source of football talent and football fandom. But up to this day, it had never won a professional football championship.

Art Rooney founded the NFL's Pittsburgh Steelers on May 19, 1933. He and his wife, the former Kathleen "Kass" McNulty, lived in the Troy Hill section of the North Side of Pittsburgh, and raised 5 sons. They were Dan, Art Jr., Tim, Patrick and John. They would have 32 grandchildren and 75 great-grandchildren.

Art Jr. said that Art Sr., known to all of Western Pennsylvania as "The Chief," always told his sons, "Treat everybody the way you'd like to be treated. Give them the benefit of the doubt. But never let anyone mistake kindness for weakness." Or, as Art Jr. put it, "He took the Golden Rule, and put a little bit of the North Side in it."

The Steelers were founded when they were because 1933 was the year the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania finally repealed the "blue law" prohibiting professional sports on Sunday. This also enabled the Philadelphia Eagles to be founded on July 8, 1933.

Both teams struggled for years. Indeed, the manpower drain of World War II led them to merge the teams for the 1943 season, and the team was nicknamed the "Steagles." In 1947, at last, the Steelers finished 1st in the NFL's Eastern Division. Well, in a tie for it. With the Eagles. And the Eagles won a Playoff at Pittsburgh's Forbes Field.

That was the closest the Steelers would get to an NFL Championship Game for another quarter of a century. In 1955, Dan and Art Jr. seemed to be the only people at Steeler training camp to notice a young Pittsburgh native who was trying to make the team as a quarterback. But Art Sr. deferred to his head coach, a run-centric old-schooler named Walt Kiesling.

Kiesling is not well-remembered today. The young quarterback is: He was picked up by the Baltimore Colts, and he made that team, and himself, legend. He was Johnny Unitas.

If Art Sr. had died shortly after the Jets won Super Bowl III on January 12, 1969, it would have been said that the best thing he did for his team was to die, so that his son could run the team. Instead, his sons held what we would now call an "intervention," telling him that they should take over the operations of the team. He agreed -- and lived another 20 years, in which the sons turned the Steelers from a joke franchise into an iconic team of American sports.

Pretty much the first thing that Dan Rooney did was offer the Steelers' head coaching job to the head coach at nearby Penn State, Joe Paterno. Paterno turned him down. So Dan offered it to the defensive coordinator of the team the Jets had just beaten in the Super Bowl, who had been on the staff of the San Diego Chargers team that won the 1963 AFL Championship, and a lineman who had won 2 NFL Championships with the Cleveland Browns: Chuck Noll.

Dan put his brother Art Jr. in charge of the team's drafts. His drafts included:

* 1969: Defensive tackle Joe Greene, offensive tackle Jon Kolb and defensive end L.C. Greenwood.

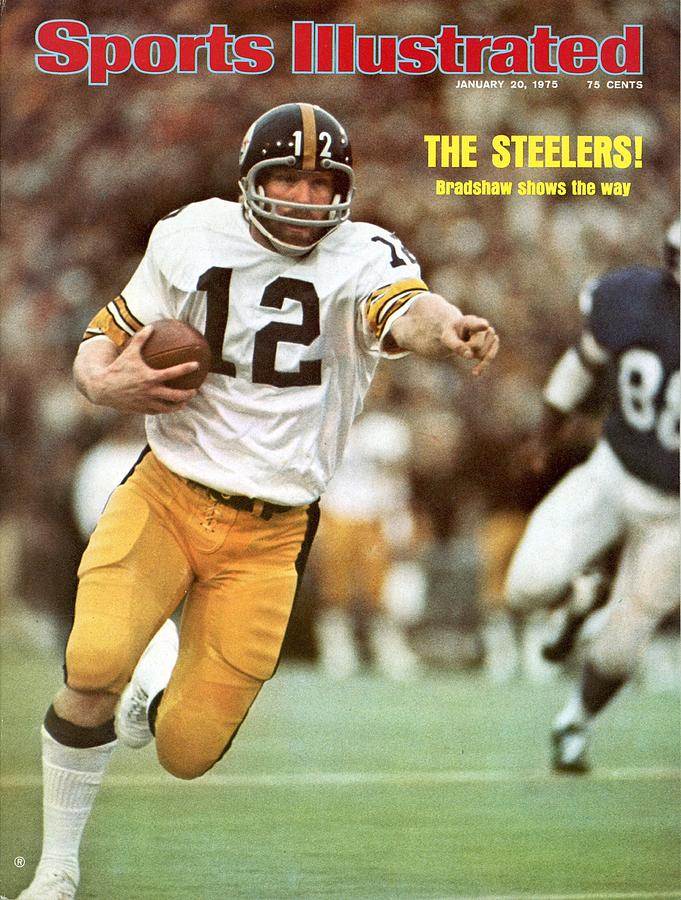

* 1970: Quarterback Terry Bradshaw and cornerback Mel Blount.

* 1971: Linebacker Jack Ham, guard Gerry Mullins, defensive tackles Dwight White and Ernie Holmes, tight end Larry Brown, and safety Mike Wagner.

* 1972: Running back Franco Harris and defensive tackle Steve Furness.

* And in 1974, in perhaps the greatest single draft in NFL history, he selected receivers Lynn Swann and John Stallworth, linebacker Jack Lambert, and center Mike Webster -- 4 Hall-of-Famers in one draft. And that's not counting safety Donnie Shell, who wasn't drafted in 1974, but was signed anyway, and is in the Hall.

Counting Greene, Bradshaw, Blount, Ham and Harris, that was 10 Hall-of-Famers in 6 drafts. Counting Noll, 11 -- all based on the decisions of Dan Rooney and Art Rooney Jr. To put that in perspective: The team had 5 players from 1933 to 1968 who ended up making the Hall.

Counting Greene, Bradshaw, Blount, Ham and Harris, that was 10 Hall-of-Famers in 6 drafts. Counting Noll, 11 -- all based on the decisions of Dan Rooney and Art Rooney Jr. To put that in perspective: The team had 5 players from 1933 to 1968 who ended up making the Hall.

It took a while to build a winner, especially because Noll and Bradshaw had a contentious relationship. Moving from 1925-built Pitt Stadium into the new Three Rivers Stadium in 1970 helped. In 1972, the Steelers went 11-3, won the AFC Central Division Championship, and reached the AFC Championship Game, thanks to a pass Bradshaw threw that deflected off Oakland Raider safety Jack Tatum and ended up being caught and taken in for a Divisional Playoff-winning touchdown by Harris, known as "the Immaculate Reception."

They made the Playoffs again in 1973, going 10-4. But they didn't make the Super Bowl either time. In 1974, they went 10-3-1, and won the AFC Central Division again. In the Divisional Playoff, they beat the Buffalo Bills, 32-14 at Three Rivers. This would be the only Playoff game of O.J. Simpson's career: Although he caught a touchdown pass, he couldn't help the Bills win, and he never got to another.

They had to go to the Oakland Coliseum to win the AFC Championship -- this would be the last season that a rotation chose the site of the Conference Championship games, rather than which team had the better record -- and beat the Raiders, 24-13. They would play Super Bowl IX at Tulane Stadium in New Orleans, site of the annual Sugar Bowl, against the Minnesota Vikings.

Both teams had named defenses. Reminiscent of the Iron Curtain across Europe, the Steelers' front seven was known as the Steel Curtain: Tackles Greene and White, ends Greenwood and Holmes, and linebackers Lambert, Ham and the veteran Andy Russell. The Vikings, due to their jersey color reminding people of Sheb Wooley's novelty song that hit Number 1 in 1958, had a defense known as the Purple People Eaters. So it's not surprising that Super Bowl IX was one of the lowest-scoring championship games in NFL history.

Western Pennsylvania had been hit hard over the last 10 years. The coal and steel industries had severely declined. The industries that would replace them and get Pittsburgh, if not the small towns nearby, back on its feet -- computers and health care -- had not yet arrived. Labor unions were losing power.

"White flight" increased the population of the suburbs, but dropped that of the city itself. The city's population peaked at 676,806 in the 1950 Census, but was down to 520,117 in 1970. This decline continues, having reached 302,971 in 2020. The metropolitan area dropped from 2.8 million in 1960 to 2.3 million in 2010, but has gained a little back since then.

The city's sports teams had always been a rallying point, but were also inconsistent. Like the nursery rhyme about the little girl with the curl in the middle of her forehead, when they were good, they were very, very good; but when they were bad, they were horrid.

The city had a team in the NBA during its inaugural season of 1946-47, the Pittsburgh Ironmen, but they failed after that season. The Pittsburgh Condors won the title in the 1st season of the American Basketball Association, 1967-68. But when their biggest star, Connie Hawkins, had his ban from the NBA (due to an overreaction to his role in a point-shaving scandal) lifted in 1969, he went to the Phoenix Suns, and the Pipers were doomed. A rebranding to the Pittsburgh Condors in 1970 didn't help, and they folded in 1972.

The NHL granted the Steel City an expansion team in 1967, the Pittsburgh Penguins. They made the Playoffs in 1970 and '72, and would again in '75, but, at the time, they were nothing special. By far the most successful team in town was the baseball team, the Pirates. They had won the National League Eastern Division title in 1970, '71, '72, '73 and '74, and would again in '75. But aside from 1971, they couldn't win a Pennant. They won the World Series that year, but the death of Roberto Clemente in a plane crash after the 1972 season cast a pall over them that left them unable to return to the Fall Classic.

But football was the sport in Pittsburgh, and in all of Western Pennsylvania. It was especially known for producing great quarterbacks, such as Unitas (from Bloomfield on the city's East Side), Johnny Lujack (Connellsville, 50 miles southeast of downtown), George Blanda (Youngwood, 36 miles southeast), and Joe Namath (Beaver Falls, 30 miles northwest). Later would come Joe Montana (New Eagle, 23 miles south), Dan Marino (South Oakland, on the East Side) and Jim Kelly (East Brady, 57 miles northeast).

Still, the city was looking for its 1st pro football championship. It hadn't happened in the NFL. And the city didn't have teams in any of the AFLs, or the AAFC. Now, it looked to Coach Noll, the Steel Curtain, and Bradshaw, "the Blond Bomber" from Shreveport, Louisiana, to get that 1st title.

A full house of 80,997 fans filed into Tulane Stadium. Despite the Vikings having been to the Super Bowl the year before (losing to the Miami Dolphins), and 4 years before that (losing to the Kansas City Chiefs), the Steelers were favored by 3 points. The weather was bad: 46 degrees, with the artificial turf field a bit slick due to rain the previous day. (The game was supposed to be played indoors at the Superdome, but construction delays forced that stadium's opening to the following August.)

Talk about low-scoring: Not only did the 1st quarter end 0-0 (the Steelers' Roy Gerela missed 2 field goal attempts, and the Vikings only got 20 total yards), but the only score of the 1st half was the 1st safety in Super Bowl history.

Fred Cox missed a field goal for the Vikings. On their next possession, Viking quarterback Fran Tarkenton pitched the ball behind him to Dave Osborn. That may have been his name, and he may have been in the Super Bowl, but unlike the daredevil character created by comedian Bob Einstein, this Dave Osborn was not super: He never had control of the ball, and Tarkenton, known as a "scrambler," ran to the ball and fell on it. White just had to touch him, and it was 2-0 Steelers.

The Steelers got a drive going in the 3rd quarter, and Franco Harris ran the ball in for a touchdown and a 9-0 Pittsburgh lead. And that would be all the scoring in the game's 1st 45 minutes. The Steelers forced a fumble in the 4th quarter, but had the tables turned when the Vikings blocked one of their punts, and Terry Brown recovered the ball in the end zone. But Cox missed the extra point. With 10:33 to go, the Vikings trailed only 9-6. Through the 2023 season, that remains the closest the Vikings have ever come to becoming World Champions.

So often derided as dumb, Bradshaw proved he was a smart quarterback. He launched an 11-play, 66-yard drive, ending with a 4-yard pass to Brown. The touchdown put the Steelers up 16-6 with 3:31 left. Tarkenton threw a pass that was intercepted by Wagner, and the Steelers ran the clock down as much as they could. With 38 seconds left, there was nothing the Vikings could do.

The Pittsburgh Steelers were World Champions. Harris was named the game's Most Valuable Player. At the time, Noll was the youngest man ever to coach a team to victory in the Super Bowl: He had just turned 42. Pete Rozelle said his happiest moment in his 29 seasons as Commissioner of the NFL was handing the Vince Lombardi Trophy to Art Rooney Sr. -- but it was because of the building done by Dan and Art Jr.

Art Sr. wanted it. The organization as a whole, and even Western Pennsylvania as a whole, needed it. The Steelers would reach 4 Super Bowls (IX, X, XIII and XIV), winning all of them, in a span of 6 years.

All tolled, under Dan Rooney's operation, 48 seasons, they reached the Playoffs 29 times, won 22 Division titles (15 in the old AFC Central, 7 in the AFC North following the 2002 realignment), reached 16 AFC Championship Games, won 8 AFC Championships, and won 6 Super Bowls, the most NFL Championships in the Super Bowl era. He also built Heinz Field (now Acrisure Stadium), the Steelers' new home, for the 2001 season, and it is one of the best stadiums in the NFL.

The Steelers became a cultural phenomenon, with their black and gold uniforms, their helmets with the "Steelmark" logo on only the right side with the left side remaining blank, their multi-ethnic working-class fan base, and their bright yellow Terrible Towels being waved in the stands (first at Three Rivers Stadium, then at Heinz Field).

Much like Liverpool Football Club in England, the Steelers had great success in the 1970s, in a city hit hard by industrial decline, where the "football" team meant everything. As with the 1965 Los Angeles Dodgers and the 1968 Detroit Tigers with their World Series wins following race riots, a community in another kind of trouble rallied around a great team, to lift them up, to show a country that had been looking down on them that they were still entitled to some pride.

The fact that the Steelers stood up, usually successfully, to the Dallas Cowboys and the Oakland Raiders, 2 of the most hated NFL teams nationwide, also helped boost their national image. Along with the Cowboys, the Raiders, the Green Bay Packers (due to their similar cultural stamp in the 1960s) and the Chicago Bears (ditto for the 1980s), the Steelers are one of the few NFL teams to have a nationwide fan base. In New York and New Jersey, 400 miles from Pittsburgh, you can see Steeler bumper stickers and window stickers on cars every day.

The fact that the Steelers stood up, usually successfully, to the Dallas Cowboys and the Oakland Raiders, 2 of the most hated NFL teams nationwide, also helped boost their national image. Along with the Cowboys, the Raiders, the Green Bay Packers (due to their similar cultural stamp in the 1960s) and the Chicago Bears (ditto for the 1980s), the Steelers are one of the few NFL teams to have a nationwide fan base. In New York and New Jersey, 400 miles from Pittsburgh, you can see Steeler bumper stickers and window stickers on cars every day.

Art Rooney Sr. died in 1988, and Dan became majority owner, replacing Noll with Bill Cowher in 1992. By that point, Art Jr. had reduced his involvement in the team. The Steelers won the 1995 AFC Championship, but history was turned on its head, and the Steelers lost Super Bowl XXX to the Cowboys.

In 2003, Dan followed in his father's footsteps, and handed over day-to-day operations to his son, Art Rooney II (grandson of the founder and nephew of Art Jr.). It was Art II who oversaw the building of the teams that won Super Bowls XL and XLIII and lost Super Bowl XLV, and in 2007 replaced the retiring Cowher with his assistant, Mike Tomlin, the team's 1st black head coach. Dan died in 2017.

No comments:

Post a Comment