Roger Gilbert Bannister was born on March 23, 1929, in Harrow, West London. He went to University College School in his hometown, and medical school at the University of Oxford and at St. Mary's Hospital Medical School, which is now part of Imperial College London.

He was 8 years old on August 28, 1937, when fellow Englishman Sydney Wooderson ran a mile in 4 minutes, 6.4 seconds at Motspur Park in London. This was a world record. On July 1, 1942, the record was reduced to 4:06.2 by Swedish runner Gunder Hägg, who then began alternating holding the record with another Swede, Arne Andersson. (Sweden was neutral during World War II, and thus its best athletes were not off fighting.) On July 17, 1945, between V-E Day and V-J Day, Hägg reduced the record to 4:01.4.

After The War, Wooderson challenged the Swedes to match races, and he usually beat them, eventually setting a personal best and a British record -- but not breaking the world record. They inspired Bannister, and when he arrived at Oxford in 1946, he began running on their Iffley Road Track.

He began training for the 1948 Olympic Games -- the Olympics use not the mile run but the 1,500 meters, a.k.a. "the metric mile" -- to be held in his hometown of London, but he believed he wasn't ready. He may have been right: While he did run in the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Finland, he finished 4th in the 1,500, but he did set a British record. The race was won by Josy Barthel of Luxembourg. Bannister had reduced his mile time to 4:08.3 at the 1951 Penn Relays in Philadelphia, his 1st visit to America.

The mile record was still Hägg's 4:01.4 in 1945. A mile is 1,609 meters, so it was a shade over 4 laps around a traditional 400-meter track. It was a nice round number, a perfect match: 4 laps, 4 minutes, 1 minute per lap on the average. If, one day, someone runs a mile in under 3 minutes, as amazing as that would be, it wouldn't have the same impact -- just as the 1st Earth person's walk on the planet Mars will never be as celebrated as the 1st such walk on the Moon was in 1969.

And in the early 1950s, there were people who believed that a sub-4-minute mile was not physically possible. There was a myth that there were those who believed that any man who broke it would die in so doing, but Bannister, as a medical student, knew that such an occurrence was unlikely. In fact, as Bannister said in the memoir he published a year after the feat, he said that there was no such widely-held belief.

On May 2, 1953, at Iffley Road, he ran a mile in 4:03.6, setting a new British record. Now, he was sure: "This race made me realize that the 4-minute mile was not out of reach." On June 27, in Surrey, he ran a mile in 4:02.0. Now, in all of human history to that point, only Hägg and Andersson had been timed in a mile run faster.

But, as with the Wright Brothers trying for the 1st heavier-than-air flight, and Charles Lindbergh for the 1st nonstop flight between the United States and the European continent, the efforts of others were rendering time to be of the essence. Also in 1953, American runner Wes Santee ran a mile in 4:02.4, and Australian runner John Landy matched Bannister at 4:02.0. On January 21, 1954, Landy ran 4:02.4. On April 19, he ran 4:02.4 again. Still not sub-four, and still not even beating the existing record, but a threat to them nonetheless.

*

It was May 6, 1954. Let me set the stage: Dwight D. Eisenhower was President of the United States. Winston Churchill was in his last months as Prime Minister of Britain, and Queen Elizabeth II had been monarch for a little over 2 years, and was just 28 years old. Donald Trump, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton were 7 years old, and Barack Obama wouldn't be born for another 7 years.

Edmund Hillary had become the 1st man to reach the summit of the world's highest mountain, Mount Everest in Nepal, a little less than a year earlier. Decades later, Sports Illustrated would do a joint feature on Hillary and Bannister.

Britain had just 1 TV network, the BBC; America had 3, NBC, CBS and DuMont, with ABC preparing to launch and essentially replace DuMont. Color televisions were few and far between. Rock and roll was just getting started. Cordless telephones, never mind mobile ones, were out of the question. Computers took up entire sides of buildings. The Subway fare in New York had gone up to 15 cents the year before.

There were 48 States. The U.S. Supreme Court was days away from ordering the desegregation of public schools. There were 3 Major League Baseball teams in New York City, none south of Washington and Cincinnati, and none west of St. Louis. Joe DiMaggio had recently married Marilyn Monroe. There were 6 teams in the NHL, and the NBA was an afterthought, barely integrated, with teams in cities as small as Syracuse, Rochester and Fort Wayne, and the 24-second shot clock hadn't yet happened.

About 1,200 people gathered for a meet between Oxford University runners and the British AAA (Amateur Athletic Association), at the Iffley Road Track, not a bad crowd for a Thursday early evening, with the meet broadcast live on BBC Radio (not on television), and iffy weather.

How iffy was it? It was damp, and the wind was measured at 25 miles per hour -- meaning that, if sub-four was done that day, it wouldn't be counted as a world record by the governing body of world track & field, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF). With this in mind, Bannister thought that trying for the record would be a waste, and he'd try at a later meet. But he was kept in the lineup, and shortly before the race was to begin, the wind stopped. Any record(s) set at the meet, in any event, would count.

Bannister, now 25 years old, would run, wearing Number 41 (well before Tom Seaver became identified with the number), for the AAA team. He was no longer eligible to run for Oxford, because he had since gotten his degree, and had actually had to take a train from London's Paddington Station to Oxford to get to the meet.

Six men ran. For the AAA team: Bannister, Chris Chataway, Chris Brasher and Tom Hulatt. For Oxford: Alan Gordon and George Dole. Nigel Miller arrived at the match, and only found out that he was due to run when he read the meet program. He didn't have a uniform with him, and couldn't find one, and had to drop out. Would the record have happened if there'd been 7 men racing instead of 6? We'll never know.

At 6:00 PM -- 1:00 in the afternoon, New York time -- the starter fired his pistol. After 1 lap, Brasher led, with a time of 57.5 seconds. The pace was on. After 2 laps, Brasher still led, with a time of 1 minute and 58 seconds. The pace was still on. Chataway took the lead, and at the end of the 3rd lap, he led with a time of 3 minutes and 0.7 seconds. The pace was no longer on.

Bannister took the lead with about 300 yards, about half a lap, to go. With about 275 yards to go, he went into his finishing kick. He took the lead, and broke the tape. He had won, beyond any doubt, but that was secondary to his real goal. Did he break the record? Did he break the barrier?

The meet announcer was Norris McWhirter. The next year, with his twin brother Ross, he would, appropriately enough, begin publishing The Guinness Book of World Records. And this is what he said:

Ladies and gentlemen, here is the result of event nine, the one mile: First, Number 41, R.G. Bannister, Amateur Athletic Association, and formerly of Exeter and Merton Colleges, Oxford, with a time which is a new meeting and track record, and which, subject to ratification, will be a new English Native, British National, British All-Comers, European, British Empire and World Record. The time was three...

Nobody heard the rest of it, because they roared in approval and drowned it out. The nice round number of 4 minutes even, the barrier thought impenetrable, had been broken. The time was 3 minutes, 59.4 seconds. Bannister had lowered the 9-year-old world record by 2 seconds, or about 0.8 percent. The times of the laps: 57.5 seconds, 1 minute and 0.5 seconds, 1 minute and 2.7 seconds, 58.4 seconds.

And since it was broadcast on the BBC, the world knew about it quickly. Special editions of newspapers were published all over the world. It was done in plenty of time to make the evening papers in North America.

The Daily Express, one of London's tabloid newspapers

As I said, it was not broadcast on television, but it was filmed, so you can watch it happen, with Bannister's own voiceover.

*

The record didn't stand long. Just 46 days. Indeed, despite his monumental achievement, no one has ever officially held the record for the mile for a shorter time. On June 21, 1954, John Landy ran in a meet in Turku, Finland, and reduced the record from 3:59.4 to 3:57.9 -- a second and a half less.

The Empire Games -- the British mini-Olympics, now known as the Commonwealth Games -- were coming up, and a mile race between Bannister and Landy had to happen. It was the running equivalent of the Heavyweight Championship of the World. It was called The Mile of the Century and The Miracle Mile.

The site was the new Empire Stadium in Vancouver. The date was August 7, 1954. A much larger crowd came out: 35,000. Bannister competed for England (not "Great Britain"), Landy for Australia. They were then the only 2 men ever to run a mile in under 4 minutes, and Landy held the record.

In the 3rd lap, Landy had a 10-yard lead. But Bannister caught up, and, on the final turn, Landy made a critical mistake: He turned his head to his left, to see how far behind Bannister was. In fact, Bannister was on his right, and was thus able to pass Landy and win the race. The time was 3:58.8 -- a new personal best for Bannister, but short of Landy's record.

"To everything -- turn, turn, turn --

there is a season -- turn, turn, turn...

A time to gain, a time to lose."

In 1967, a statue of the men would be dedicated at Empire Stadium. Landy said, "While Lot's wife was turned into a pillar of salt for looking back, I am probably the only one ever turned into bronze for looking back."

*

On August 29, 1954, Bannister won the 1,500 meters at the European Championships in Bern, Switzerland. The newly-founded magazine Sports Illustrated named him their 1st-ever Sportsman of the Year.

Note the English rose on his jersey.

Behind him, a Canadian runner with a maple leaf.

He never ran another competitive race. He retired to focus on his medical career, forfeiting a chance at the 1956 Olympics. This might have been for the best, as they were held in Melbourne, Australia, Landy's hometown. But Landy only won the Bronze Medal in the 1,500 meters, with the Gold Medal going to Ron Delany of the Republic of Ireland -- a country that was, and remains, proudly not in the British Commonwealth.

Interestingly, given his inspirations, Bannister married a Swede, Moyra Jacobsson. He had literally met her just the day before his achievement. They had, perhaps appropriately, 4 children: Sons Clive and Thurstan, and daughters Erin and Charlotte.

He spent 40 years as a practicing neurologist, publishing more than 80 papers, and becoming director of the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases in London, before retiring and moving back to Oxford.

He also became the 1st Chairman of the Sports Council, now known as Sport England, rapidly increasing central and local government funding of sports centers, and initiating the 1st testing for anabolic steroids in sports, anywhere in the world. It was for this, rather than his 1954 achievement, that the Queen knighted him, making him Doctor Sir Roger Gilbert Bannister, Companion of Honour, Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

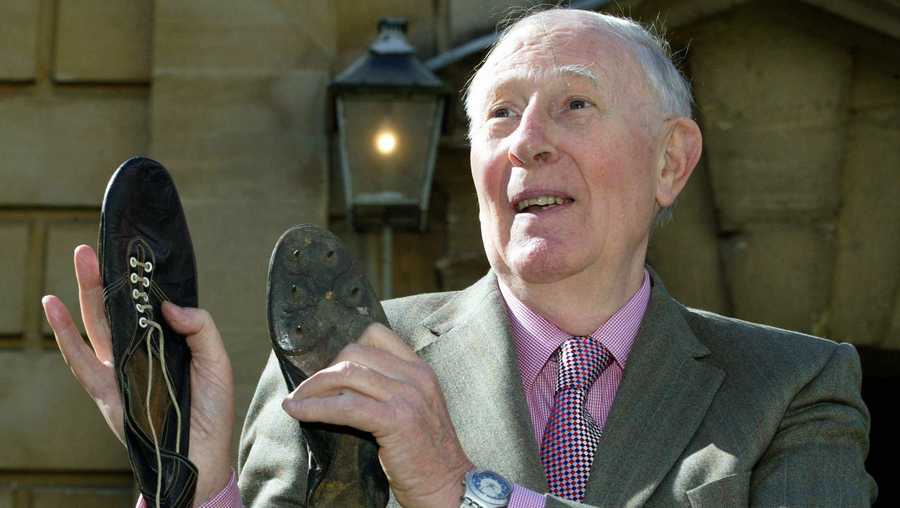

Dr. Sir Roger Bannister, May 6, 2004,

the 50th Anniversary of the 1st sub-four mile,

with the shoes he wore in the race

In 2011, he was, with some irony given his line of work, diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. But he was still healthy enough to take part in the Torch Relay for the 2012 Olympics in London, carrying it on the Iffley Road Track. In another irony, on his last visit to Iffley Road, on the 60th Anniversary of the event, May 6, 2014, he was in a wheelchair. He died yesterday, March 3, 2018, shortly before what would have been his 89th birthday.

*

As for the other notables:

John Landy would later be an environmental activist, writing 2 books on the subject, and serve as Governor of the Australian State of Victoria, which includes Melbourne, from 2001 to 2006. He will be 88 years old if he is still alive on this coming April 12. (UPDATE: He died on February 24, 2022, at 91.)

Ron Delany worked for a ferry company, and turns 82 this coming Tuesday. Josy Barthel, the 1952 Gold Medalist, worked for the Luxembourg sports federation, and died in 1992, at the age of 65.

Chris Brasher won the Gold Medal in the 3,000-meter steeplechase at the 1956 Olympics, became a journalist, designed camping equipment, and co-founded the London Marathon in 1981. He died in 2003, age 74.

Chris Chataway -- or Sir Christopher Chataway -- won the 3-mile race at the 1954 Empire Games, but never won an Olympic medal. He went into broadcasting, and served in the British Parliament from 1959 to 1966, and again from 1969 to 1974. He then served as Chairman of Britain's Civil Aviation Authority, and was knighted for his services therein. He died in 2014, age 82.

Norris McWhirter edited the Guinness Book alone following his brother Ross' 1975 murder by the Irish Republican Army, in London at age 50. Norris lived until 2004, age 78.

Here is the progression for the record in the mile run:

May 6, 1954: Roger Bannister, England, at Oxford, England, 3:59.4.

June 21, 1954: John Landy, Australia, at Turku, Finland, 3:58.0.

July 19, 1957: Derek Ibbotson, England, at London, 3:57.2

August 6, 1958: Herb Elliott, Australia, at Dublin, Ireland, 3:54.5.

January 27, 1962: Peter Snell, New Zealand, at Whanganui, New Zealand, 3:54.4.

November 17, 1964: Snell again, at Auckland, New Zealand, 3:54.1.

June 9, 1965: Michel Jazy, France, at Rennes, France, 3:53.6.

July 17, 1966: Jim Ryun, the 1st American to hold the record since Glenn Cunningham in 1937, at Berkeley, California, 3:51.3.

June 23, 1967: Ryan again, at Bakersfield, California, 3:51.1.

May 17, 1975: Filbert Bayi, Tanzania, at Kingston, Jamaica, 3:51.0.

August 12, 1975: John Walker, New Zealand, at Göteborg, Sweden, 3:49.4.

July 17, 1979: Sebastian Coe, England, at Oslo, Norway, 3:48.95. It was now possible to record the time to the nearest 1/100th of a second.

July 1, 1980: Steve Ovett, England, also at Oslo, 3:48.80.

August 19, 1981: Coe again, at Zürich, Switzerland, 3:48.53.

August 26, 1981: Ovett again, at Koblenz, Germany, 3:48.40.

August 28, 1981: Coe again, the 3rd new record in 9 days, at Brussels, Belgium, 3:47.33.

July 27, 1985: Steve Cram, England, at Oslo, 3:46.32.

September 5, 1993: Noureddine Morceli, Algeria, at Rieti, Italy, 3:44.39.

July 7, 1999: Hicham El Guerrouj, Morocco, at Rome, Italy, 3:43.13. (UPDATE: As of May 6, 2022, this record still stands.)

Chris Brasher won the Gold Medal in the 3,000-meter steeplechase at the 1956 Olympics, became a journalist, designed camping equipment, and co-founded the London Marathon in 1981. He died in 2003, age 74.

Chris Chataway -- or Sir Christopher Chataway -- won the 3-mile race at the 1954 Empire Games, but never won an Olympic medal. He went into broadcasting, and served in the British Parliament from 1959 to 1966, and again from 1969 to 1974. He then served as Chairman of Britain's Civil Aviation Authority, and was knighted for his services therein. He died in 2014, age 82.

Norris McWhirter edited the Guinness Book alone following his brother Ross' 1975 murder by the Irish Republican Army, in London at age 50. Norris lived until 2004, age 78.

Here is the progression for the record in the mile run:

May 6, 1954: Roger Bannister, England, at Oxford, England, 3:59.4.

June 21, 1954: John Landy, Australia, at Turku, Finland, 3:58.0.

July 19, 1957: Derek Ibbotson, England, at London, 3:57.2

August 6, 1958: Herb Elliott, Australia, at Dublin, Ireland, 3:54.5.

January 27, 1962: Peter Snell, New Zealand, at Whanganui, New Zealand, 3:54.4.

November 17, 1964: Snell again, at Auckland, New Zealand, 3:54.1.

June 9, 1965: Michel Jazy, France, at Rennes, France, 3:53.6.

July 17, 1966: Jim Ryun, the 1st American to hold the record since Glenn Cunningham in 1937, at Berkeley, California, 3:51.3.

June 23, 1967: Ryan again, at Bakersfield, California, 3:51.1.

May 17, 1975: Filbert Bayi, Tanzania, at Kingston, Jamaica, 3:51.0.

August 12, 1975: John Walker, New Zealand, at Göteborg, Sweden, 3:49.4.

July 17, 1979: Sebastian Coe, England, at Oslo, Norway, 3:48.95. It was now possible to record the time to the nearest 1/100th of a second.

July 1, 1980: Steve Ovett, England, also at Oslo, 3:48.80.

August 19, 1981: Coe again, at Zürich, Switzerland, 3:48.53.

August 26, 1981: Ovett again, at Koblenz, Germany, 3:48.40.

August 28, 1981: Coe again, the 3rd new record in 9 days, at Brussels, Belgium, 3:47.33.

July 27, 1985: Steve Cram, England, at Oslo, 3:46.32.

September 5, 1993: Noureddine Morceli, Algeria, at Rieti, Italy, 3:44.39.

July 7, 1999: Hicham El Guerrouj, Morocco, at Rome, Italy, 3:43.13. (UPDATE: As of May 6, 2022, this record still stands.)

On June 1, 1957, Don Bowden became the 1st American to run a mile in under 4 minutes, going 3:58.7 in Stockton, California.

On February 10, 1962, Jim Beatty, a New Yorker running in the Los Angeles Invitational at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena, became the 1st person to run a mile in under 4 minutes indoors: 3:58.9. It was broadcast live on ABC Wide World of Sports, and it was considered a big coup for ABC Sports, as well as for Beatty.

The women's record in the mile currently stands at 4:12.56, set by Svetlana Masterkova of Russia, at Zürich on August 14, 1996. It has stood for over 21 years, longer than even the men's record.

The Empire Stadium in Vancouver has since been demolished. The Bannister-Landy statue now stands at the Pacific National Exhibition, which includes the Pacific Coliseum, the former home of the NHL's Vancouver Canucks.

The Iffley Road stadium at Oxford, which opened in 1876, is still in use. But after the Taylor Report, and its recommendations for English sports facilities in the wake of the 1989 Hillsborough Stadium Disaster, its seating capacity was reduced to 499. At 500 or over, it would have been too expensive to maintain. The track is now named the Roger Bannister Track, and has long since been upgraded from cinder to rubber.

Three minutes, fifty-nine point four seconds.

Andy Warhol once said, "In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes." Roger Bannister was famous for less than that, or so it seemed. But those 4 minutes, minus 6/10ths of a second, made him a legend forevermore.

Of course, to paraphrase Dr. Archibald "Moonlight" Graham, the brief Major League Baseball player turned small-town physician in the novel Shoeless Joe and its film version Field of Dreams, If Roger Bannister had only gotten to be a doctor for 4 minutes, now that would have been a tragedy.

UPDATE: Dr. Sir Roger Bannister was buried at Wolvercote Cemetery in Oxford.

No comments:

Post a Comment