And he may have been better than any of them.

Yelberton Abraham Tittle Jr. was born on October 24, 1926 in Marshall, Texas, in the northeastern corner of the Lone Star State. Learning that the greatest of all Texas-born football players, Sammy Baugh, had practiced throwing footballs through a tire swing, he did the same thing. In 1943, he quarterbacked Marshall High School to an undefeated season.

He was recruited by Louisiana State University, and since World War II caused a manpower drain, the NCAA temporarily rescinded its prohibition on freshmen playing varsity sports (which it would strike down for good in 1972). LSU won only 2 games in 1944, but 1 was over arch-rival Tulane, in which Tittle through for 238 yards, then a school record.

In 1946, LSU beat Tulane again, and was awarded a berth in the Cotton Bowl in Dallas -- not quite Tittle's hometown, but the closest big city to it. More than 20 years before a game in Green Bay got the nickname, this game was called the Ice Bowl, as the field at the Cotton Bowl was covered with ice in frigid weather. Tittle was able to move the ball a little, but nobody moved it much, and the game with Arkansas ended in a 0-0 tie.

When I was a kid, I saw a little sports trivia book, and it had this question: "Who was the only man to hit a home run off Sandy Koufax and catch a touchdown pass from Y.A. Tittle?" It was Tittle's predecessor as LSU's starting quarterback, future New York Giants shortstop Alvin Dark.

*

Tittle was chosen by the Detroit Lions in the 1st round of the 1948 NFL Draft, but he signed with the Baltimore Colts of the All-America Football Conference instead. The Lions went after another quarterback from Texas, Bobby Layne, and did all right. With the Colts, Tittle was 1948 AAFC Rookie of the Year. They joined the NFL for 1950, but were bankrupt, and folded. A new Colts would start in 1953.

The San Francisco 49ers took Tittle in the dispersal draft. In 1951 and 1952, he split quarterbacking duties with Frankie Albert, one of the earliest lefthanded quarterbacks. He became the starter in 1953, and led the Niners to a 9-3 record, the 1st of several near-misses for him.

In 1954, the 49ers had the only backfield ever to be fully comprised of future members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Behind Tittle were halfback Hugh McElhenny and fullbacks John Henry Johnson and Joe "the Jet" Perry. They were called the Million Dollar Backfield ($1 million then would be about $9.2 million today, or about $2.3 million per year per man), and the hype was such that, on their issue dated November 22, 1954, Tittle became the 1st pro football player to appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

Tittle reminisced, "It made quarterbacking so easy, because I just get in the huddle, and call anything, and you have 3 Hall of Fame running backs ready to carry the ball." But he also said, "They should have called us the Hundred Dollar Backfield, because that's about what we were paid."

The Million Dollar Backfield lasted all of 6 games. The 49ers beat the Lions, the Washington Redskins, the Green Bay Packers and the Chicago Bears, and tied the Los Angeles Rams. But on Halloween, October 31, McElhenny got his shoulder separated, and the 49ers lost 31-27 to the Chicago Bears, and their championship aspirations were ruined. This was a run of losing 4 out of 5, and they finished 7-4-1. (Don't blame The Dreaded SI Cover Jinx: This was before Tittle was on the cover.)

The backfield was kept together for 2 more seasons, but won nothing. Johnson was traded before the 1957 season, and a new player, receiver R.C. Owens, made his mark when he jumped high in the air to catch Tittle passes, a play that became known as "the alley-oop." The Niners tied the Lions for the Western Division title, losing a Playoff. This would be as close as they would get to an NFL Championship for 13 years. They wouldn't get closer for another 24 years.

In 1960, a new coach came in, Red Hickey, and he became the 1st NFL coach to use the shotgun formation. This enabled him to use 2 young quarterbacks at once, John Brodie and Billy Kilmer. Tittle had become marginalized. He was 34, and it seemed his days as a starting NFL quarterback were over.

*

But after the 1st preseason game in 1961, Tittle was traded to the New York Giants, rejuvenating his career. He was actually younger than the quarterback the Giants had: Charlie Conerly, who had led them to the 1956 NFL Championship and back to the Championship Game in 1958 and '59, was 40. Tittle led the Giants to the Eastern division Championship, and was voted by the NFL players as League Most Valuable Player. But the Giants got clobbered by the Packers in the Championship Game, 37-0.

On October 28, 1962, the day the Cuban Missle Crisis was resolved, Tittle tied an NFL record with 7 touchdown passes in a 49-34 win over the Redskins. In the season finale, he threw 6 in a 41-31 win over the Dallas Cowboys, setting a new NFL record with 33 touchdown passes on the season. Again, the Giants won the Division. Again, they advanced to the Championship Game. This time, it was at home at Yankee Stadium. But again, the Packers won, 16-7.

Tittle had to be talked out of retirement in 1963. At 37, he set a new record with 36 touchdown passes, and he was named MVP by the Associated Press. He was a bigger star than ever, even appearing as the "mystery guest" on CBS' What's My Line?

Again, he got the Giants into the Championship Game. This time, it was against the Bears at a chilly Wrigley Field. In the 2nd quarter, he was tackled by Larry Morris and wrecked his knee. But he kept playing, gamely trying to finally win that elusive title. But he threw 5 interceptions, 4 after the injury, and the Bears won, 14-10.

The Giants seemed to get old all at once. On September 20, 1964, the Giants played the Pittsburgh Steelers at Pitt Stadium. John Baker hit Tittle hard enough to give him a concussion, crack his sternum, and injure the cartilage in his ribs. Chuck Hinton, who later played for the Jets, intercepted the pass that Tittle threw, and returned it for a touchdown. The Steelers won, 27-24.

There were no hard feelings: Baker later ran for Sheriff in Wake County, North Carolina, and Tittle went there to campaign for him during one of his re-election bids. He served 24 years.

Morris Berman of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette took a picture of Tittle kneeling on the grass after the hit, blood dripping from his famously bald scalp. While the P-G refused to publish it, preferring what it called "action shots," Berman took it to Life magazine, which published it in its October 2, 1964 issue. The photo became iconic, with Charlton Heston re-enacting it while playing an aging quarterback in the 1969 film Number One.

It was the beginning of the end, for Tittle and that generation of Giants. They finished 2-10-2 that season. "That was the end of the road," Tittle later said. "It was the end of my dream. It was over." But, at the time, he held most of the major career passing records that would later be broken by Johnny Unitas, then Fran Tarkenton, then Brett Favre, then Peyton Manning, then Tom Brady: 4,395 passes, 2,427 completions, 33,070 yards, 242 touchdowns, and 39 rushing touchdowns for a quarterback.

*

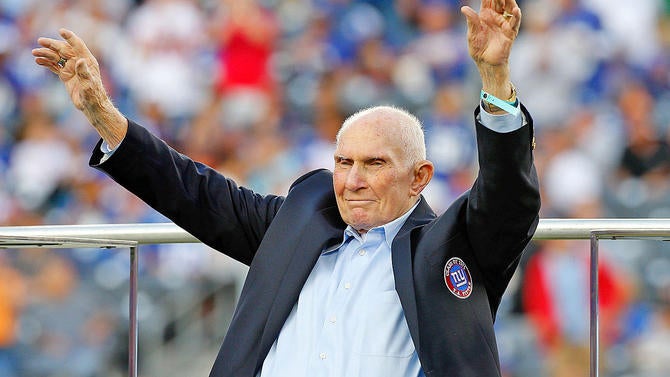

He was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, the Texas Sports Hall of Fame, the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame, the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame, the San Francisco 49ers Hall of Fame, and the New York Giants Ring of Honor. The Giants retired his Number 14. He later served as an assistant coach for the 49ers and the Giants, and returned to the Bay Area, launching an insurance and financial services company.

With Giants teammate Frank Gifford

On October 31, 1994, 40 years to the day after the Million Dollar Backfield got derailed, he appeared with another New York quarterbacking legend, Joe Namath of the Jets, and Packer linebacker icon Ray Nitschke, in a Halloween-themed cold open for ABC's broadcast of a Monday Night Football game between the Packers and the Bears. (I have it on videotape somewhere. It doesn't seem to be on YouTube, nor does a photo seem to be on Google Images.)

He lived out his life in Atherton, the same town on "The Peninsula," San Mateo County south of San Francisco, where Willie Mays lived (and still does at this writing). He married a fellow LSU student named Minnette, and they had sons Michael, Patrick and John, and a daughter, Dianne Tittle de Laet, who wrote a biography, Giants & Heroes: A Daughter's Memories of Y.A. Tittle.

Minnette died in 2012. By this point, dementia had begun to take over, making Tittle yet another of the old-time NFL players affected by the many head shots that players take. In 2014, ESPN.com published a story by Seth Wickersham, about Dianne taking him back to Marshall and Baton Rouge, to trigger his memories one more time, and to get him talking about his experiences.

Y.A. Tittle died on October 8, 2017, at a hospital in Stanford, California, just short of his 91st birthday. A long life of defying many foes ended, as there is one foe that eventually stops caring about every person's defiance.

That foe erased Y.A. Tittle's memories. It cannot erase his place in the collective memory. For as long as people talk about football, they will talk about him. He earned that.

UPDATE: He was buried near the Stanford campus, at Alta Mesa Memorial Park in Palo Alto.

No comments:

Post a Comment