And neither the Yankees nor the Mets came out of it looking good.

On Sunday, the anniversary of the Yankee event in question, I'll post about it. Today is the anniversary of the Met event in question.

June 15, 1977, 40 years ago: The Yankees trade Mike Fischlin, Randy Niemann and a player to be named later (who, after the season, turns out to be Dave Bergman) to the Houston Astros for Cliff Johnson.

This is easily the best trade made by a New York baseball team on the day, as Johnson becomes Thurman Munson's backup catcher and a key righthanded bat off the bench for the Yankee teams that win the 1977 and '78 World Series. But it is not the trade that anyone ends up talking about that week.

In June 1977, the Mets were, for the moment, still the most popular team in New York City, riding their rather incomplete successes of the 1969 World Series win and the 1973 National League Pennant (but losing the World Series). They remained the most popular team despite not really following up, and despite the Yankees having won the 1976 American League Pennant.

M. Donald Grant was a friend of Joan Payson, the founding owner of the Mets. She hired him to be the team's 1st chairman of the board. After the 1969 season, the Mets owned New York, even more than the Jets did. After the 1973 season, when they'd won another Pennant, they were so far ahead of the Yankees it wasn't funny -- though you can be sure Met fans were cackling with glee.

Surely, with their new ballpark and exciting young players in a nice neighborhood, they had the advantage over the Yankees, with their old ballpark and failing players in a disastrous neighborhood, not to mention their crazy new owner.

The Mets, or rather Grant, frittered away so much of that goodwill, to the point where a few Met fans -- not many, but a few, including a Brooklyn-born-and-raised college student and aspiring filmmaker, Shelton "Spike" Lee -- switched to the Yankees after they returned to the top, a rise coinciding with the Mets' collapse.

Grant was the son of Mike Grant, a member of the Hockey Hall of Fame, winning the Stanley Cup with the Montreal Victorias in 1895, 1896, 1897 and 1898; and the Winnipeg Victorias (not the same team) in 1899 and 1900. This was when hockey was all-amateur.

But after trying his hand at amateur hockey in Montreal, "Don" Grant came to New York in the 1920s, becoming a stockbrocker. He made a lot of money in the bull market of the Roaring Twenties, and was not wiped out in the Crash of 1929. He became Mrs. Payson's personal advisor when she found out they shared a passion for horse racing.

She became a member of the board of directors of the New York Giants baseball team, and he stood in as her proxy vote on the board. On her order, he cast the only dissenting vote when the board voted to move to San Francisco after the 1957 season. Together, they worked with prominent New York attorney William A. Shea to get a new team for New York, and that's how the Mets were born: If Bill Shea is the Mets' "father" and Joan Payson its "mother," then Don Grant is... their creepy uncle.

(Yeah, I know: As someone who calls himself "Uncle Mike," I should be careful. But those of you who remember Grant, tell me he wasn't creepy.)

In 1970, shortly after the World Series win, Johnny Murphy, the former Yankee reliever who was the Mets' general manager, died. Their player development director expected to be promoted into the job, but Grant wouldn't do it, because he knew the guy wouldn't let him tell him what to do.

When manager Gil Hodges died in 1972, Grant passed the guy over for that job as well, giving it to coach Yogi Berra -- who, to be fair, had won a Pennant as manager of the Yankees in 1964, and would do so for the Mets in 1973.

The passed-over guy had enough: He went to the Kansas City Royals, and built a winner there, before crossing Missouri and doing the same thing with the St. Louis Cardinals, causing problems first for the Yankees in the 1970s and then for the Mets in the 1980s. He was Dorrel Norman Elvert "Whitey" Herzog.

Grant hired Bob Scheffing to be the GM, and he did as he was told -- including trading away Nolan Ryan in 1971, allowing Ryan to become one of the best pitchers of his generation. On Grant's orders, Scheffing traded away Tommie Agee after the 1972 season, and Tug McGraw after 1974. In 1975, Grant fired Scheffing, and replaced him with Joe McDonald, who traded away Cleon Jones and Rusty Staub after that season.

Then Mrs. Payson died. Her daughter, Lorinda de Roulet, inherited the team, and she knew that she knew nothing about baseball, so she trusted Grant even more than her mother did. After the 1976 season, in which the Mets finished 15 games out of 1st place, but were nonetheless 86-76 for a very respectable 3rd, Grant/McDonald traded away Jerry Grote. Hardly anybody from the '73, let alone '69, Pennant winners was left.

But there was still Tom Seaver, the greatest player the Met franchise had ever known. (And he still is). Along with Steve Carlton of the Philadelphia Phillies and Don Sutton of the Los Angeles Dodgers, he was still 1 of the 3 best pitchers in the NL; along with Ryan of the California Angels, Jim Palmer of the Baltimore Orioles,and Jim "Catfish" Hunter of the Yankees, 1 of the top 6 in the majors. But he was also expensive: Going into the 1977 season, he was in the middle of a 3-year contract worth $675,000.

Think about that for a moment: Tom Seaver, "Tom Terrific," "The Franchise," was making $225,000 a year. Factoring inflation in, that's about $900,000 today. For comparison's sake, the man usually regarded as the best pitcher in baseball today, Clayton Kershaw, is making $35.5 million this season -- about $8.8 million in 1977 dollars.

Granted -- no pun intended -- most MLB team owners were cheap back then. Some, notoriously so, like Walter O'Malley of the Dodgers, Charlie Finley of the Oakland Athletics, and Calvin Griffith of the Minnesota Twins. Some were forced into it by low revenue streams, like a succession of owners of the Chicago White Sox and the Cleveland Indians. A few were willing to spend, like George Steinbrenner of the Yankees, Ruly Carpenter of the Phillies, Gene Autry of the Angels and Ray Kroc of the San Diego Padres.

And then there was August Anheuser Busch Jr., owner of the brewery that sold Budweiser, and owner of the St. Louis Cardinals. Gussie Busch went to both extremes. If you did what you were told, kept your mouth shut, and showed loyalty, Gussie treated you very well, and paid you well -- as shown by a cover on Sports Illustrated magazine at the start of the 1968 World Series, showing that the Cards were the highest-paid team in baseball.

But if you asked for anything more than what he was offering, Gussie wanted nothing to do with you, and traded you. In 1971, he had offered Carlton $50,000, a pretty good salary for a pitcher at the time. Carlton wanted $60,000. Not $200,000, not $100,000, not even $65,000. $60,000. Just $10,000 more than Busch was offering. He had the stats to deserve it. Busch had all that beer money, and should have been too big of a man to quibble over ten thousand bucks. He traded Carlton to the Phillies, and it took the Cards 10 years to recover.

M. Donald Grant -- he really hated it when people referred to him that way -- was cheap. Not because the Mets weren't making money. And even if they weren't, it wasn't his money: Mrs. de Roulet was a de Roulet by marriage, and both a Payson and a Whitney by blood. She was richer than George Steinbrenner. She could afford to spend whatever she wanted.

But she trusted Grant, and he thought baseball players were beneath him. He had what Marvin Miller, director of the players' union, called "a plantation mentality." When Seaver, who lived in Stamford, Connecticut during the season (and his native Fresno, California in the off-season), joined the nearby Greenwich Country Club, Grant was furious: "Who do you think you are, joining the Greenwich Country Club?"

Seaver eventually told the New York Daily News that, during the negotiations over the contract that was paying him $225,000 a year, Grant asked Seaver, "What are you, some sort of Communist?"

Tom Seaver was not a Communist. He was a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps, having served during, if not in, the Vietnam War. I looked it up: M. Donald Grant never served in the military, neither in his native Canada nor in his adopted America. (Being born in 1904, he was 14 when World War I ended, and 35 when Canada entered World War II, so he was not going to be drafted.)

Seaver and Grant in happier times, 1972.

They are probably not discussing that year's Presidential election

between Richard Nixon and George McGovern.

As might have been said on Match Game 77 at that time: "Dumb Donald is so dumb!" "How dumb is he?" Well, actually, M. Donald Grant wasn't so much dumb as he was out of touch. How out of touch was he? I once saw a Met-themed blog whose author wrote that Grant tried to explain what he was doing with Seaver in terms of "bluffing and playing tricks in a hand of bridge."

How many average baseball fans know how to play the card game bridge, a.k.a. contract bridge? I consider myself a fairly smart person. I can play poker and gin rummy. I've never even seen bridge being played. It's usually considered a rich person's game. Well, M. Donald Grant was a rich person.

His son, Michael Donald Grant III, who goes by Michael Grant, said, "He was a formal kind of guy, but he wasn't an aristocrat or a blue blood. It annoyed him that he was given the image of a stuffed shirt."

Well, tough shit, M. Donald. Regardless of your father's success at amateur hockey, you had no more business running a professional sports team than you would have a trucking company.

Seaver thought that, even at $225,000 a year, he was underpaid. He knew that, across town, Catfish was making $640,000; as the 1st free agent of the modern era, his salary was well-publicized. Also well-publicized was the $230,000 that the Cleveland Indians were paying free agent pitcher Wayne Garland, whose career would be cut short by that season's injury.

Seaver may not have known that Carlton was making less than he was, $160,000. Or that Palmer was making more than he was: $250,000. Or that Sutton was also making $250,000. (O'Malley often reluctantly paid stars big, but average players very little.)

Noting 2 other pitchers whose names will shortly come up: He may not have known that Luis Tiant of the Boston Red Sox was making $185,000, or that Ryan's California Angels teammate Frank Tanana was making $225,000.

But he did know that his teammate, Jerry Koosman, who had, in 1976, become the 2nd Met, after Seaver, to win 20 games in a season was making $150,000. And he knew that Ryan was making $200,000.

And how did he know this? Because their wives, Nancy Seaver and Ruth Ryan, remained close friends after Nolan was traded. Women talk.

Let me say this again: Seaver was making $225,000, Ryan $200,000. Tom Seaver was making more money than Nolan Ryan. Baseball-Reference.com, the most authoritative historical baseball source there is, confirms this. If anybody said that Ryan was making more money, and that Seaver was thus jealous of Ryan over this, that anybody was a liar. He was also making more than Luis Tiant, and exactly as much as Frank Tanana.

Again: Anybody saying that those 3 guys were making more money than Seaver was flat-out lying. And anybody saying that Seaver was saying that those 3 guys were making more was flat-out lying.

Still, Seaver thought he was underpaid. Given that he was the Mets' biggest drawing card, he was right: In the 8 home games that he started, the Mets got an average per-game attendance of 23,257; the 17 home games he didn't start, they averaged 11,913, about half as much.

Seaver wanted to remain a Met for the rest of his career, but wanted more money and over a longer period of time, guaranteed. He decided to go over Grant's head, and asked Mrs. de Roulet for a contract extension. She agreed to it. No problem, right?

Wrong: Grant acted as though he was the true owner of the Mets, and took this as a grave personal insult. (Well, maybe it was, but he deserved it.) Apparently, he was okay for him to call a wartime U.S. Marine veteran who was the greatest player his team had ever had "a Communist," but it wasn't okay for said player to go over his head to his boss.

He probably also didn't like that his boss was a woman. After all, unlike Mrs. Payson, Mrs. de Roulet was not an old friend. He probably thought of her as "the kid."

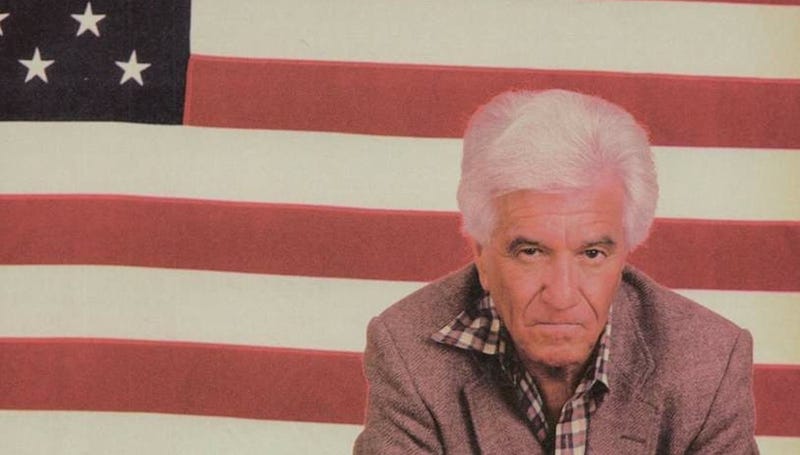

Grant went to Dick Young, longtime baseball columnist for the Daily News. Once a liberal crusader who stood up for Jackie Robinson, Young was now 59 years old. Years of hard drinking had lined his face and turned his hair stark white. He had become embittered and conservative, as he saw what he called "my America" fading away.

Dick Young, circa 1977.

No longer Young. But very much a dick.

Aside from possibly Whitey Ford, Seaver was the best pitcher he would ever see for a New York team, but he was now tight with Grant. Grant asked him to write a column smearing Seaver. Young didn't need much convincing. He probably traded it for a drink. He was probably happy to do it.

Young's anger at Seaver may have dated to the 1969 postseason, in which Seaver made public statements like, "If the Mets can win the World Series, we can get out of Vietnam," and, "I think it's perfectly ridiculous what we're doing about the Vietnam situation. It's absurd!" Seaver would later say, "I wasn't opposed to all wars. I wasn't a confirmed pacifist. But I did feel that this particular war was wrong."

Here is a summary of the most infamous sports column in the history of New York newspapers, from the Daily News of June 15, 1977 -- at the time, June 15 was the trading deadline in MLB:

In a way, Tom Seaver is like Walter O’Malley. Both are very good at what they do. Both are very deceptive in what they say. Both are very greedy.

Greed is greed, whether it is manifested by an owner or a ballplayer...

Tom Seaver is after more money. He wants to break his contract with the Mets. “Renegotiate” is the pretty word he used for it in this time of pretty words.

So, Tom Seaver said, over and over, that the Mets were not competitive in the free agent field. He said the front office was not spending money the way it should. He made it appear that he wanted the money to be spent on others, but really he wanted it to be spent on him. He talked ideals, but actually he was talking hard cash.

Like O’Malley, Tom Seaver couldn’t say that out loud. How would it sound for Tom Terrific, All-American boy, to disavow a contract he had signed in good faith?...

“Tom, we can’t do that,” said Grant. “I have a board of directors to account for. Were you happy when you signed your contract?”

“Yes, I was, but things have changed.”

“You asked for more money than had ever been paid to any pitcher, and you got it.”

“That’s not so anymore,” said Seaver.

“Who gets more?”

“Tiant, Ryan, Tanana.”

“I don’t know about that,” said Grant, “but it was you who opted for a three year contract. If we renegotiate for you, we would have every player on the team in the office. Please see the light of day. I beg you to reconsider and be the Tom Seaver happy to play with the Mets.”

“You want me to be happy at your terms.”

“Yes, and you want to be happy only on your terms, and that’s a standoff. I have told you 10 times we don’t want to trade you. Of the cities you prefer, we have our best offer from Cincinnati. If that can crystallize, we’ll make it.”

Tom Seaver’s base pay is $225,000, and he could do $250,000 with a good year. Luis Tiant does not make $225,000. Frank Tanana, by threatening to play out his option, received a $1 million signing bonus from Gene Autry, but his base salary of $200,000 is below Seaver’s. Nolan Ryan is getting more now than Seaver, and that galls Tom because Nancy Seaver and Ruth Ryan are very friendly and Tom Seaver long has treated Nolan Ryan like a little brother.

It comes down to this: Tom Seaver is jealous of those who had the guts to play out their option or used the threat of playing it out as leverage for a big raise — while he was snug behind a three-year contract of his choosing. He talks of being treated like a man. A man lives up to his contract...

*

Young had lied through his dentures about what Seaver said, and his reasons for wanting to renegotiate. That was bad enough. But he had also brought Seaver's wife into the lies -- and Ryan's wife, too.Young wrote about what "a man" does. A man may disagree with another man, but a man does not bring the other man's family into it. That is a line that a man does not cross. Ever.

You got a problem with someone? Fine. But leave the family out of it. By playing Major League Baseball, Tom Seaver had made himself a public figure. Nancy Seaver was not a public figure until Dick Young made her one, and for what? Selling a few newspapers, and doing his pal M. Donald Grant a big fat favor.

"That Young column was the straw that broke the back," Seaver told the Daily News in 2007, on the 30th Anniversary. "Bringing your family into it, with no truth whatsoever to what he wrote. I could not abide by that. I had to go."

I know what it is like to work for a man who doesn't respect you, and lies to you, and treats you like garbage. Seaver knew what I later found out: Sometimes, you get to a point where no other circumstance matters, and you can no longer work for your boss. The well had been poisoned -- by Grant and Young, not by Seaver.

According to the Young column, Grant had told Seaver that the Cincinnati Reds had made the best trade offer for him. Seaver took Grant at his word one last time, and accepted a trade to Cincinnati.

"Come on, George... " said George Thomas Seaver,

trying to maintain control of his emotions at the press conference,

calling himself by his rarely-used first name,

As the Daily News' front page put it, "His wish is M. Don Granted."

In exchange for the legend, 32 years old but still one of the game's top pitchers, the Mets got:

* Steve Henderson, 24, who made his major league debut for the Mets the next day, and became a decent hitter and a good left fielder, finishing 2nd in the NL Rookie of the Year voting, behind Andre Dawson of the Montreal Expos.

* Doug Flynn, 26, stuck behind Joe Morgan in Cincinnati, but became one of the best-fielding 2nd basemen in baseball in Flushing Meadow, winning a Gold Glove in 1980, although never making an All-Star Team and never becoming much of a hitter.

* Pat Zachry, 25, a pitcher who had finished in a 1st place tie in the vote for the previous year's NL Rookie of the Year, with pitcher Butch Metzger of the San Diego Padres -- but, stricken by injury, would himself be traded to the Mets in 1978, ending his career with them that season. Zachry would be an All-Star in 1978, going 10-6 for a bad Met team.

* And Dan Norman, 22, a right fielder who made his major league debut that September, and never amounted to much; essentially, a throw-in, to make it look like the Mets had actually gotten 4 serviceable major leaguers for Seaver.

And yet, by Opening Day 1981, Henderson and Norman would be gone; by Opening Day 1982, so would Flynn; by Opening Day 1983, so would Zachry. By the time Seaver pitched his last major league game, Henderson was the only 1 of the 4 still playing in the majors.

True, the Mets didn't exactly get nothing for Seaver. That would happen when, after the new regime brought him back in 1983, a clerical mistake caused them to lose him as a free-agent compensation pick to the Chicago White Sox after the season. They got some value for him in 1977.

They still didn't get as much value for Seaver as Seaver gave the Reds from June 18, 1977 to August 15, 1982 (a season cut short by injury), including 2 more All-Star seasons in 1978 and 1981, pitching the only no-hitter of his career in 1978, leading the NL in shutouts and getting them to its Championship Series in 1979, leading it in wins and winning percentage in 1981, nearly winning a 4th Cy Young Award that year, and, also that year, notching his 3,000th career strikeout, against the St. Louis Cardinals, the victim being future Met legend Keith Hernandez.

Aside from the Dodgers and Giants getting moved out of town, this is the most hated transaction in the history of New York sports.

And it wasn't the only Met trade of the night: They also sent Dave Kingman, the surly slugger who would go on to hit 442 home runs but, strikeout-prone, would have a lifetime batting average of .236, to the Padres.

What did they get from San Diego for "Kong"? Paul Siebert, a nothing pitcher who would throw his last major league pitch for the Mets in 1978, only 25. And a once-greatly-heralded prospect, now a 27-year-old banged-up utility player who could no longer hit, and would play his last major league game just 2 years later. He would, however, later write his name into Met history. His name was Bobby Valentine.

The Padres didn't keep Kingman long, soon trading him to the Angels, who then waived him, and he was picked up for the stretch run by the Yankees, making him the 1st man to play for 4 major league teams in 1 season in the 20th Century, and the 1st man to play for the Mets and the Yankees in the same season. He was not, however, included on the Yankees' ALCS or World Series roster.

Interestingly, when the Mets got Kingman back in 1981, from the Chicago Cubs, where he'd thrived, the player they sent to get him was Steve Henderson.

With Watergate and its "Saturday Night Massacre" -- which happened mere hours after Seaver was the losing pitcher when the Mets lost Game 6 of the 1973 World Series -- still fresh in the memory, and the Yankees having made a trade in 1974 that was known as "the Friday Night Massacre," these 2 Met trades became known as "the Midnight Massacre."

The effect on attendance was staggering. The following Saturday, June 18, was Banner Day, and the Mets drew 52,784, nearly a sellout. On August 21, not just a Sunday but also Seaver's 1st game back with the Reds, the Mets drew 46,265. Minus those 2 games, their average attendance from June 16 to September 23, 1977 (their last home date of the season) was 13,243 -- only a little more than they were getting without Seaver before the trade, and 10,000 per game less than they got when he pitched.

The face is Tom's. The ballpark is Shea.

But the uniform never looked right on him.

In hindsight, it had to be done. Either Seaver or Grant had to go, and Grant had the power, so he wasn't going anywhere.

And, let's be honest about this: Having Seaver, even if the Mets had those other 4 players as well, would have made no difference: The Mets were nowhere near Playoff contention from 1977 to 1982, when he was in Cincinnati, and his pitching wouldn't have won enough games to get them into contention.

There is even a theory that suggests that losing Seaver may have been for the best, since the Mets would have been a little better, and wouldn't have accumulated the draft picks that helped build The Dynasty That Never Was, including the 1986 World Championship. In other words, had Tom Seaver stayed, the Mets would not have won the World Series since 1969 -- not once in my entire lifetime -- and we would now be talking about the Curse of Amos Otis, instead of the Curse of Kevin Mitchell.

And, let's be honest about this: Having Seaver, even if the Mets had those other 4 players as well, would have made no difference: The Mets were nowhere near Playoff contention from 1977 to 1982, when he was in Cincinnati, and his pitching wouldn't have won enough games to get them into contention.

There is even a theory that suggests that losing Seaver may have been for the best, since the Mets would have been a little better, and wouldn't have accumulated the draft picks that helped build The Dynasty That Never Was, including the 1986 World Championship. In other words, had Tom Seaver stayed, the Mets would not have won the World Series since 1969 -- not once in my entire lifetime -- and we would now be talking about the Curse of Amos Otis, instead of the Curse of Kevin Mitchell.

But from a public relations standpoint, the deal was a nightmare. It made the Mets organization look petty, bush-league, like profits were more important than Playoffs, and obedience more important than performance. It made them look, as Wayne Gretzky would say of the New Jersey Devils in 1983, like "a Mickey Mouse organization."

The world of baseball had changed, to the point where players now had the freedom to get paid based on performance, and to play where they wanted; and M. Donald Grant was saying, essentially, "No, the world has not changed, not on my watch!"

Throw in the fact that the Yankees were titleholders in the American League, had a renovated Yankee Stadium that was better than Shea, had the defending AL Most Valuable Player in Thurman Munson, had the game's best relief pitcher in Sparky Lyle, and had recently acquired the game's most charismatic slugger in Reggie Jackson, and any pretensions the Mets had to being the most popular, and the most respected, baseball team in New York were gone. Until 1984, anyway.

For Met fans, this was, to borrow Don McLean's phrase about the 1959 plane crash that killed Buddy Holly, "The Day the Music Died." They treated it as if their childhood was over. They reacted to it the way their parents (or big brothers) did when the Dodgers (or Giants) left in 1957. They cried over this as if Seaver had died. As if Seaver had been assassinated by M. Donald Grant, and their youth had died with him.

Babe Ruth left the Yankees in 1935. Joe DiMaggio retired in 1951. Mickey Mantle retired in 1969. Reggie Jackson was not re-signed in 1981. Mariano Rivera retired in 2013, and Derek Jeter retired in 2014. On none of those occasions did Yankee Fans react like a child who had been told his dog was "taken to a farm upstate."

There were 2 times when Yankee Fans did react like that. The 1st was for Lou Gehrig in 1939. Except he actually was going to die. The 2nd was for Thurman Munson in 1979. And he actually

did die.

Great players leave. Great players come to take their places. It was time for Met fans to grow up.

*

In February 1978, 8 months after the trade, Grant was asked when the Mets would be contenders. He said, "We are contenders right now."

Was he full of shit? Or just delusional?

Lorinda de Roulet finally fired the old buzzard in 1978. By that point, attendance at Shea Stadium was so sparse, it was being called Grant's Tomb: It had gone from a City record 2.7 million fans in the 1970 season to under 800,000 by 1979 -- or, per game, from 33,000 to 9,740. Contrast that with the Yankees: In 1972, they bottomed out at 966,000 (12,000 per game), their lowest since World War II; by 1980, they had risen to 2.6 million (32,000).

The world of baseball had changed, to the point where players now had the freedom to get paid based on performance, and to play where they wanted; and M. Donald Grant was saying, essentially, "No, the world has not changed, not on my watch!"

Throw in the fact that the Yankees were titleholders in the American League, had a renovated Yankee Stadium that was better than Shea, had the defending AL Most Valuable Player in Thurman Munson, had the game's best relief pitcher in Sparky Lyle, and had recently acquired the game's most charismatic slugger in Reggie Jackson, and any pretensions the Mets had to being the most popular, and the most respected, baseball team in New York were gone. Until 1984, anyway.

For Met fans, this was, to borrow Don McLean's phrase about the 1959 plane crash that killed Buddy Holly, "The Day the Music Died." They treated it as if their childhood was over. They reacted to it the way their parents (or big brothers) did when the Dodgers (or Giants) left in 1957. They cried over this as if Seaver had died. As if Seaver had been assassinated by M. Donald Grant, and their youth had died with him.

Babe Ruth left the Yankees in 1935. Joe DiMaggio retired in 1951. Mickey Mantle retired in 1969. Reggie Jackson was not re-signed in 1981. Mariano Rivera retired in 2013, and Derek Jeter retired in 2014. On none of those occasions did Yankee Fans react like a child who had been told his dog was "taken to a farm upstate."

There were 2 times when Yankee Fans did react like that. The 1st was for Lou Gehrig in 1939. Except he actually was going to die. The 2nd was for Thurman Munson in 1979. And he actually

did die.

Great players leave. Great players come to take their places. It was time for Met fans to grow up.

*

In February 1978, 8 months after the trade, Grant was asked when the Mets would be contenders. He said, "We are contenders right now."

Was he full of shit? Or just delusional?

Lorinda de Roulet finally fired the old buzzard in 1978. By that point, attendance at Shea Stadium was so sparse, it was being called Grant's Tomb: It had gone from a City record 2.7 million fans in the 1970 season to under 800,000 by 1979 -- or, per game, from 33,000 to 9,740. Contrast that with the Yankees: In 1972, they bottomed out at 966,000 (12,000 per game), their lowest since World War II; by 1980, they had risen to 2.6 million (32,000).

Not until 1980 did things begin to turn around at Shea. That was the year when Lorinda sold the team to Fred Wilpon and Nelson Doubleday. They hired Frank Cashen, who helped build the Baltimore Orioles team that dominated the American League from 1966 to 1971, as general manager. His drafts and trades built the Mets into a contender by 1984, and a World Champion in 1986.

Tom Seaver was not killed by M. Donald Grant on June 15, 1977. His life and career continued to flourish. He even came back to the Mets for 1983, though only for 1983.

He won his 300th game in New York City on August 4, 1985 -- pitching for the White Sox against the Yankees at Yankee Stadium. I was there: It was Phil Rizzuto Day, and there were 54,000 fans on hand, half of them Yankee Fans there to honor the Scooter, half of them Met fans there to see Tom Terrific notch the milestone.

He retired after the 1986 season -- in which he was with the Boston Red Sox, and might have pitched against the Mets in the World Series, had he not been injured. The Mets retired his Number 41 in 1988. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1992. He had already assisted ABC on its baseball broadcasts while still active, including during the 1977 World Series that the Yankees won. He later broadcast for the Yankees from 1989 to 1993, playfully bantering with Rizzuto; and for the Mets from 1999 to 2005.

In 2008, he threw out the ceremonial last pitch at Shea Stadium. The next year, he threw out the first pitch at Citi Field. He is now 72 years old, still married to Nancy, they have 2 daughters, and they are still close friends with Nolan and Ruth Ryan. They still have a home in Connecticut, and they own a vineyard in Northern California's Napa Valley, producing fine wine. There is a rumor going around that the Mets will honor him with a statue in 2019, as part of the celebrations of the 50th Anniversary of the 1969 "Miracle."

M. Donald Grant died on November 29, 1998, at the age of 94, not having been involved in professional sports for the last 18 years of his life. He died 16 days after the death of the Jets' title-winning head coach, Wilbur "Weeb" Ewbank, and 12 days after the death of the Knicks' title-winning head coach, William "Red" Holzman. Weeb and Red got a lot of praise in the New York media at the time. Grant's death was barely even noticed. Serves him right.

Moral of the story? Never trust a businessman named Donald in New York City -- especially in Queens. Incidentally, that boss I mentioned? He was from New York City, albeit Staten Island rather than Queens, but his name was Donald.

Lorinda de Roulet is still alive, age 85, but hasn't been involved in professional sports since selling the Mets, 37 years ago.

Tom Seaver made his 1st start for Cincinnati on June 18, 1977. That would also turn out to be an epic day in the saga of New York baseball -- but because of what happened with the Yankees, and it would be even uglier than the way Seaver was forced out of the Mets.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/60074771/tom_seaver_getty2.0.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment