March 26, 1963: The Cincinnati Royals beat the Syracuse Nationals, 131-127 at the Onondaga County War Memorial Arena in Syracuse, New York. Despite the Nats' Lee Shaffer leading all scorers with 45 points, 32 from Oscar Robertson leads the Royals to victory in this deciding Game 5 of the NBA Eastern Conference Semifinals.

The Royals went on to lose the Eastern Conference Finals to the Boston Celtics. The Nationals never played again. At least, not as the Nats. The following season, they moved to become the Philadelphia 76ers, taking the place of the Warriors, who had moved to San Francisco in 1962.

The Nats were founded in 1946, as members of the Midwest-based National Basketball League. In 1949, they were one of 7 NBL teams admitted to the Northeast-based Basketball Association of America, a merger (for all intents and purposes) in a single league whose name became the National Basketball Association -- which still dates its founding to that of the BAA in 1946.

Their founding owner was Danny Biasone. He was also the father of the 24-second shot clock, which was instituted for the 1954-55 season. Biasone knew that a game was 48 minutes long. He thought a game would be best if each team took about 60 shots per game. So he divided 2,880 (the number of seconds in 48 minutes) by 120 (2 teams each taking 60 shots), and came up with 1 shot every 24 seconds. He died in 1992, having lived long enough to see the shot clock adopted everywhere (including college and high school), but not long enough to be elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame (he was finally elected in 2000).

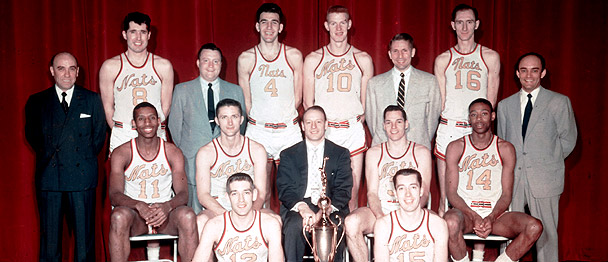

The Nats lost the 1950 and 1954 NBA Finals to the Minneapolis Lakers, and then won the 1955 NBA Championship by beating the Fort Wayne Pistons in the Finals. (Given that they'd made the Finals the year before, it's unlikely that the institution of the shot clock made the difference for them, but it did end the Lakers' dynasty.) Indeed, not until 1971-72 would the Nats/Sixers franchise play a season and fail to make the Playoffs. Even in their last season in Syracuse, they went 48-32, playing .600 ball.

By 1963, the team was in transition. Hall-of-Famer Dolph Schayes, the big hero of the 1955 title, was winding down, and was now player-coach. The players who would become the stars of the 76ers' 1967 title were beginning to come in, including Hall-of-Famer Hal Greer.

But it was getting harder and harder to run a team in such a small market. And so, Biasone sold the team to Irv Kosloff and Ike Richman, who moved the team to Philadelphia. By 1967, the 76ers were World Champions. By 1970, the New York Knicks -- 248 miles away, but at least in the same State -- had won a World Championship (and, in 1973, another), and became the Syracuse area's favorite team, as if the Nationals had never even existed.

Top 5 Reasons You

Can’t Blame the Syracuse Nationals for Moving to Philadelphia

5. The Arena Situation. From their founding in 1946 until 1951, the Nats played at the State Fair Coliseum. Built in 1927, it seated 7,500 people. It has since been renovated, with its seating capacity cut in half, and is now named the Toyota Coliseum.

From 1951 onward, the Nats played at the Onondaga County War Memorial. It seated 8,000, and was a decent arena for an NBA team of the period. It has also hosted a series of minor-league hockey teams: The Syracuse Warriors of the American Hockey League (1951-54), the Syracuse Blazers of the Eastern Hockey League (1967-77), the Syracuse Firebirds of the AHL (1979-80), and the Syracuse Crunch of the AHL (since 1994). It's also hosted arena football, minor league soccer, and lacrosse, which is popular in New York State.

It was renovated in 1994, and renamed The OnCenter War Memorial Arena. It was renovated again in 2018, and renamed the Upstate Medical University Arena at Onondaga County War Memorial. Most people still just call it "The War Memorial."

There's nothing wrong with it, as far as minor-league hockey goes. But for a modern major league sports team, it was already starting to lose its fitness by 1963. Syracuse University knew this: A year earlier, it opened Manley Field House on campus, and in 1980 built the Carrier Dome to host both baseball and football.

In contrast, in 1963, Philadelphia had the Convention Hall at its Civic Center, built in 1931 but bigger at 12,000 seats, with more amenities. The Warriors had played there from 1952 to 1962, and the 76ers would until The Spectrum opened in 1967. The Spectrum was already in the planning stages at the time of the move.

4. Television. Seeing Major League Baseball games on TV helped to kill the Negro Leagues and devastate the minor leagues. That didn't affect the NBA much, since there was almost no overlap in season.

But the rise of TV did give people a reason to stay home during basketball season. What's more, unlike MLB, boxing, horse racing and (eventually) the NFL, in the 1950s, the NBA didn't handle TV well. You'd think it would, since the court was small enough for cameras to easily follow. (Horse racing was then popular on TV because, despite having the largest "field," the horses were all bunched together, making for easy camera work.) Games were locally broadcast, but not nationally, and the teams just didn't get enough revenue from it.

3. The NBA. Like the NFL, it had started in smaller cities in the Northeast and the Midwest, and all those cities would turn out to be to small to keep the league going, and would lose their teams, except for Green Bay, Wisconsin.

There were 4 teams that didn't even survive the 1st BAA (NBA) season of 1946-47: The Pittsburgh Ironmen, the Cleveland Rebels, the Detroit Falcons and the Toronto Huskies -- and those were all big cities at the time. By the dawn of the 1950-51 season, Providence, St. Louis, Washington and even Chicago had lost their teams. The next season, Indianapolis followed. And the original version of the Baltimore Bullets, NBA Champions in 1948, folded early in the 1954-55 season.

The Royals/Kings aren't the only team that has made several moves. One of the charter BAA teams was the Buffalo Bisons. They didn't even make it to the New Year in that 1st season, moving to Moline, Illinois, next-door to Rock Island, and across the Mississippi River from Davenport and Bettendorf, Iowa. They became the Tri-Cities Blackhawks. (The region is now known as the Quad Cities.) They only stayed until 1951, became the Milwaukee Hawks, and then moved again in 1955, becoming the St. Louis Hawks, the team the Royals played in their last game in Rochester. In 1968, they moved again, becoming the Atlanta Hawks.

The Royals weren't even the only team moving in 1957: The Fort Wayne Pistons moved to Detroit. (As with the Royals, the name made even more sense in their new city than in their old one.) In 1960, the Minneapolis Lakers, winners of 5 titles, moved to Los Angeles.

In 1961, an expansion team called the Chicago Packers began. After 1 year, they became the Chicago Zephyrs, probably because Chicagoans didn't want to root for a team called the Packers. In 1963, they became the new Baltimore Bullets. In 1973, they moved to Washington. In 1997, the Washington Bullets became the Washington Wizards.

So the moving of teams wasn't something the early NBA establishment frowned upon. They would have been more surprised if the Harrison brothers had tried to stay in Rochester. Especially when there were other options.

2. Philadelphia. It was then, and is now, a great basketball city. By 1962, when the Warriors left for San Francisco, it had already seen that team win the NBA title in 1947 and 1956, and introduced Joe Fulks, Neil Johnston, Paul Arizin, and the greatest player the game has ever known, Wilt Chamberlain, to the NBA.

Philadelphia, as seen from the Museum of Art,

before the skyscraper building boom that began in the 1980s

Furthermore, by this point, the city's "Big 5" had been established: The University of Pennsylvania, Temple University, La Salle University, St. Joseph's University, and Villanova University. High school hoops were also huge, with both the Philadelphia Public League and the Philadelphia Catholic League producing local legends, in basketball and other sports.

New York likes to think of itself as the basketball city. But there are a few other contenders, and Philly is one of them. A 1986 documentary made by NFL Films, The 10 Greatest Moments in Philadelphia Sports History, said of basketball, "It is the pulse of the city, the beat on the street."

So if it was accepted that the Nationals had to move, Philadelphia was a good place to move to.

1. Western New York State. While Philadelphia's population has shrunk significantly, Syracuse didn't have a whole lot of people to lose. Even in 1963, it was home to only about 200,000 people. Today, despite being home to a major university and the New York State Fair, Syracuse has only about 150,000 people, with a metro area of only about 650,000, less than any city in North America with a major league sports team -- except for Green Bay, Wisconsin.

A recent photo of downtown Syracuse,

including the white-roofed Carrier Dome.

This is matched by the other cities in Western New York. Rochester lost the NBA's Royals in 1957. Like Syracuse, Rochester has a longtime team in minor-league hockey, the Rochester Americans. Both cities also have long had teams in baseball's Class AAA International League, the Rochester Red Wings and the Syracuse Chiefs. But not in the major leagues in either sport.

NBT Bank Stadium, home of the Syracuse Chiefs since 1997

As stated earlier, Buffalo had already lost the BAA's Bisons in 1946. Buffalo also had a team called the Buffalo Bills in the All-America Football Conference from 1946 to 1949, but when the NFL took 3 teams from the AAFC, they took the Cleveland Browns, the Baltimore Colts and the San Francisco 49ers. It became known as "The Screwing of Buffalo."

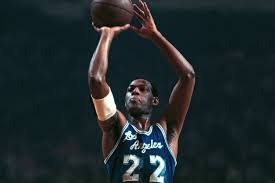

Buffalo would gain the AFL's version of the Bills in 1960, and the NBA's Braves and the NHL's Sabres in 1970, the same year the Bills became part of the AFL-NFL merger. The Braves would move in 1978, and are now the Los Angeles Clippers. And the Bills and Sabres have both faced the possibility of having to move. Today, both are still struggling, despite both being owned by billionaires Terry and Kim Pegula.

Remember the movie It's a Wonderful Life? George Bailey (played by Jimmy Stewart), operator of a building and loan association, is shown what his New York State hometown of Bedford Falls would have been like if he had never been born.

He sees that the company his father had founded had gone out of business, because George wasn't there to save it; the low-income housing George had built wasn't built; Henry Potter, the miserable old man who controlled everything in town but the building and loan, had changed the town's name to Pottersville; and, like an organized crime boss, he let other businessmen do what he pleased, so long as he got his cut.

And what businesses were doing well? Bars and casinos. The very things that, today, are pretty much the only businesses doing well in New York State, thanks to the local Native tribes getting casino licenses. In 2009, at the depth of a recession, a New York Times writer pointed this out, and contrasted it with the housing market that George Bailey once ran. The writer concluded that, for the sake of the future of the State of New York, the kindhearted Bailey was wrong, and the old bastard Potter was right. (And you thought the Times was a liberal newspaper.)

Put simply, New York State, from the capital of Albany on west through Syracuse, Rochester and Buffalo, simply can't support major league sports in the modern era.

VERDICT: Not Guilty. Whatever its benefits, Syracuse is not big enough to major league sports. The Nationals had to be moved.

And not once during this post did I mention the weather: Syracuse can get really cold during basketball season. (How cold is it?) It's sometimes known as Siber-cuse.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69007647/944358686.0.jpg)