Ted Williams would shout this, to no one in particular and to anyone who could hear, as he took batting practice.

And while he was slightly off on the nomenclature, he was frequently right on the description.

*

August 30, 1918, 100 years ago: Theodore Samuel Williams is born in San Diego, California. His father, Samuel, was a photographer from New York -- as was my grandfather, George Golden, who had been born on August 30, 1906. Ted's mother was May Venzor, a nurse in the Salvation Army. She was from El Paso, Texas, and of Mexican descent.

Ted rarely mentioned this, once saying, "If I had my mother's name, there is no doubt I would have run into problems in those days, considering the prejudices people had in Southern California." Although he appeared "white" enough to be allowed to play in what was then known as "organized ball," if he had embraced this side of himself, he could have been remembered as the 1st great Hispanic player in the major leagues. There had been white Cubans before him, such as the All-Star pitcher Adolfo "Dolf" Luque, but nobody anywhere near Ted's status. That would change after integration.

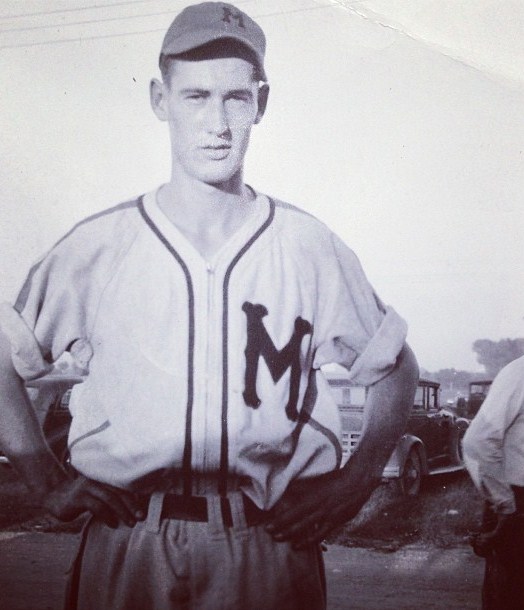

He was taught to play baseball by his uncle, Saul Venzor, who had played semi-pro ball, pitching to Yankee legends Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Joe Gordon in an exhibition game. Long after his retirement, Ted said, "All I wanted was the make the Herbert Hoover High School varsity." He did -- although it's odd that a school would have been named for Hoover during his Presidency.

It opened in 1930. Despite the Great Depression, its name has never been changed, and it is still open. Other famous graduates include another Red Sock, 1965 no-hitter pitcher Dave Morehead; 1988 World Champion Los Angeles Dodger Michael Davis; former NFL quarterback Tony Banks; 1948 Olympic long jump Gold Medalist Willie Steele; Mary "Mickey" Wright, one of the greatest female golfers; and Ted Giannoulas, a.k.a. the San Diego Chicken.

The Yankees and the St. Louis Cardinals both scouted Ted in high school, but his mother thought it was too soon for him to leave home. Fortunately, at this point, the Pacific Coast League was nearly on the same talent level as the major leagues -- or, as PCL fans called them, "the Eastern leagues." Ted signed with his hometown team, the San Diego Padres. (When San Diego got a major league team in 1969, it took the Padres name.)

For the 1st time, but not the last, Ted took a back seat to a member of the DiMaggio family: His position was left field, and the Padres' starting left fielder was Vince DiMaggio, the oldest of the brothers. Once Vince was acquired by the Boston Braves, Ted got the starting job, and the Padres won the 1937 PCL Pennant.

Eddie Collins, one of the greatest 2nd basemen who ever lived, and by this point the general manager of the Boston Red Sox, had been scouting 2nd baseman Bobby Doerr of the San Francisco Seals. But watching a game between the Seals and the Padres, he saw Ted. As he said later, "It wasn't hard to find Ted Williams: He stood out like a brown cow in a field of white cows." The Red Sox sent the Padres 2 major leaguers and 2 minor leaguers, none of whom would be easily remembered today, and $35,000 for Ted.

He spent the 1938 season with the Sox' top farm team, the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. They didn't win the Pennant that year, but Ted won the AA Triple Crown, batting .366, hitting 46 home runs, with 142 RBIs.

He made the big club, and debuted on April 20, 1939, against the Yankees, at Yankee Stadium. It was a Hall of Fame pitching matchup: Charles "Red" Ruffing for the Yankees, and Robert "Lefty" Grove for the Red Sox. Ted played right field, batted 6th, and wore Number 9, the only one he would ever wear throughout his major league career. Ruffing struck him out in the top of the 2nd, but he ripped a double to right-center in the 4th. Ruffing struck him out again in the 6th, and popped him up to 2nd in the 9th. The Yankees won, 2-0, thanks to a home run by Bill Dickey.

There was no Rookie of the Year award in 1939. If there had been, Ted, who turned 21 late in the season, would have won it easily, batting .327, hitting 31 home runs, and leading the American League with 344 total bases and 145 runs batted in -- the 1st rookie ever to lead the AL in RBIs.

He soon developed nicknames. He seemed really young, so they called him "The Kid." He was thin, but could hit, so they called him "The Splendid Splinter." He hit hard, so they called him "The Thumper." And, at some point in his career, he became so much the symbol of baseball in New England, that he was known as "Teddy Ballgame."

Sometimes, he would call himself "Ol' TSW" for his initials. Or, as I said, "Ted Fucking Williams." Or "Teddy Ballgame of the MFL." Asked to explain, he said, "That's the Major Fucking Leagues."

No, he was no angel. He wasn't a boozer, but he was a womanizer. He supposedly spit at fans once. On more than one occasion, he gave fans the middle finger. And, after making an error in left field in a 1940 game, he got booed so badly that he swore he would never tip his cap to the fans for as long as he played.

His prickly personality didn't endear him to the Boston media, either. One of the city's leading sportswriters was Dave Egan of the Boston Record, considered so authoritative that he was known as "the Colonel." Early in his career, Egan was following the team on the road, and in the hotel lobby, saw Williams come in, and asked him for an interview. Williams saw that Egan was drunk, and knew better than to give an interview to a drunk.

But that may not have been the lesser of two evils, as Egan slammed Williams in his column every chance he had. Soon, Ted had a reputation of being arrogant and aloof, never caring whether the Red Sox won or lost, so long as he got a hit.

Ted's magnum opus was the 1941 season. It's worth pointing out that, for most of the season, he was 22 years old, turning 23 late in it. At the All-Star Game at Briggs Stadium (later renamed Tiger Stadium) in Detroit, he hit a home run in the bottom of the 9th of Claude Passeau of the Chicago Cubs, turning a 5-4 National League lead into a 7-5 American League win.

Going into the last day of the regular season, which included a doubleheader with Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics at Shibe Park, his batting average was .39955. This would have been rounded up to .400, an average not achieved in the major leagues since Bill Terry of the New York Giants hit .401 in 1930.

Going into the last day of the regular season, which included a doubleheader with Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics at Shibe Park, his batting average was .39955. This would have been rounded up to .400, an average not achieved in the major leagues since Bill Terry of the New York Giants hit .401 in 1930.

The Sox manager and shortstop, Joe Cronin, told Ted that he could sit the doubleheader out if he wanted to, to protect his ".400 batting average." Ted knew the truth, and he refused to take the coward's way out.

The 1st time he came to bat in the opener, the A's catcher, Frankie Hayes, told him, "Ted, Mr. Mack told us to pitch to you." As in, we will try to get you out, but we won't try to stop you from getting to .400 by walking you, intentionally or "not."

Ted singled to right in the 2nd inning, hit a home run leading off the 5th, singled to right in the 6th, hit an RBI single to right in the 7th, and reached on an error in the 9th, by the A's 2nd baseman -- Lawrence Columbus "Crash" Davis of Durham, North Carolina, for whom the Kevin Costner character in the movie Bull Durham would be named. So the one time he didn't get a hit, he got on base anyway. Despite a 9-run A's outburst in the 5th inning, the Sox won 12-11.

Ted's batting average was now .404. Even if went 0-for-4 in the nightcap, he would still have finished at .4004 -- but going 0-for-5 would have made him .39956. He played anyway. He singled to right in the 2nd, doubled to center in the 4th, and flew to left in the 7th.

Because Pennsylvania had only legalized professional sporting events on Sunday in 1934, and had a 7:00 PM curfew for them on Sundays, the A's were already up 7-1, and Ted's .400 was secure, it was agreed between the umpires and the managers, Cronin and Mack, that the 2nd game would end after 8 innings, thus denying Ted a 4th at-bat in the game.

He finished the season with 185 hits in 456 at-bats, for a batting average of .405701754, rounded off to .406. He also finished with a league-leading 37 home runs and 120 RBIs -- not surprising, since, for 1940, the Sox had fenced off an area in right field at Fenway Park, and moved the bullpens there, to make it easier for Ted. The pens, and the seats behind them, became known as Williamsburg.

The Sox pitcher in the 2nd game was former A's star Lefty Grove. It was the last appearance of a Hall of Fame career in which he went 300-141.

Joe DiMaggio of the Yankees was awarded the American League MVP for 1941. Red Sox fans, now 3 generations removed, remain angry about this. They say Ted's .406 average was a greater achievement than DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak the same season. They forget that the award is Most Valuable Player, not Most Outstanding Player. Ted's great season did not get the Red Sox the Pennant, finishing 2nd, 17 games behind the Yankees. Joe's great season put the Yankees on a run that led to them winning the World Series.

There would be another MVP controversy in 1942. Ted batted .356, hit 36 home runs, and had 137 RBIs. Each of these led the League, giving him the Triple Crown. But the Sox finished 2nd to the Yankees, and the MVP went to their 2nd baseman, Joe Gordon. How do you deny a Triple Crown winner the MVP? Again: Most Valuable Player, not Most Outstanding Player.

Incidentally, the American League runners on base when Ted hit that walkoff homer in the '41 All-Star Game? Joe DiMaggio and Joe Gordon. (DiMaggio did get a hit in that game, but it didn't count toward his hitting streak, which was then 49 games.)

*

World War II was already underway. In January 1942, Ted was classified 1-A: "Available for unrestricted military service." In other words, the next time there was a draft, Ted could be chosen. A friend reminded Ted that he was now the sole support of his mother, and should appeal. He did, and was reclassified 3-A: "Registrant deferred because of hardship to dependents."

Boston fans, no longer caring that he was a .400 hitter the year before, booed him throughout his Triple Crown season. Opposing fans booed him, too. Quaker Oats dropped him as a spokesman. He had loved their products, but never ate their products again.

Ted had had enough. He joined the Navy Reserve, missed the entire 1943 season on active duty as a pilot trainee, and on May 2, 1944, was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps, as a flight instructor.

Ted didn't see combat in World War II, but would also miss the 1944 and 1945 seasons. He rejoined the Sox for 1946, and hit 3 home runs with 8 RBIs in the 1st game of a doubleheader against the Cleveland Indians. Lou Boudreau, the Indians' manager, invented the infield shift -- in his case, it was called the Boudreau Shift or the Williams Shift. He moved the shortstop (himself) to between 1st and 2nd base, daring Ted, a noted pull hitter, to hit to he opposite field. Did it work? Sort of: Ted grounded to Boudreau twice, but also doubled and walked.

On June 9 of that year, against Fred Hutchinson of the Detroit Tigers -- later to manage the Cincinnati Reds to the 1961 NL Pennant -- hit a drive 502 feet into the center field bleachers. Joe Boucher, a construction engineer from Albany, New York, sat there, and the ball hit him on the head, wrecking his straw hat. The wooden bleachers were replaced by plastic seats in 1976, but the location was noted: It is Section 42, Row 37, Seat 21. In 1984, it was painted red, and it remains "The Red Seat" today.

That year, the All-Star Game was held at Fenway. Ted hit a home run off Kirby Higbe of the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 4th inning. In the 7th, the National League brought in Rip Sewell of the Pittsburgh Pirates. He had a blooper that he called the "eephus pitch." It had been hit, but no one had yet hit it for a home run. Ted did it, and Sewell, in his 4th All-Star Game, was never the same pitcher.

This time, the Red Sox ran away with the Pennant, led by Ted, Doerr, Dom DiMaggio (Joe's brother, also a center fielder), shortstop Johnny Pesky (Cronin was still the manager, but had retired as a player), and pitchers Dave "Boo" Ferriss and Cecil "Tex" Hughson. It was their 1st Pennant since 1918, before selling several players to the Yankees, including Babe Ruth. This time, there was no denying Ted: He batted .342, hit 38 home runs, and had 123 RBIs (oddly, none of these led the AL), and he was an easy choice for MVP.

Then came the World Series. The opposition was the St. Louis Cardinals. Led by the NL's answer to Ted, Stan Musial, the Cards were in their 4th World Series in 6 years, having won in 1942 and 1944, and lost in 1943. But Ted was nursing an elbow injury, and only batted .200, 5-for-25. Stan didn't hit well, either, and neither would end up the big story of the Series.

The Series went to a Game 7 at Sportsman's Park in St. Louis. It was tied 3-3 in the bottom of the 8th. It should be noted that Dom DiMaggio had been injured earlier, and Leon Culberson was now in center field for Boston. Enos Slaughter was on 1st base, and took off with a pitch to Harry Walker, who hit a drive to right-center. Mel Allen, the Yankees' main broadcaster, was covering the Series for NBC despite the Yankees not being in it, and his surviving radio broadcast shows him saying, "Culberson fumbles with the ball momentarily."

Slaughter turned his head, saw this, and realized he could score all the way from 1st. Culberson threw the ball back to the infield. Pesky got it, and... Well, I've seen the film a few times. I can't really say he "hesitated" or "held the ball," as people have been saying for the last 72 years. I don't think it would have mattered, as Slaughter probably would have been safe at the plate anyway. It was 4-3 St. Louis, and that's how it ended.

The Sox had won 104 games, a record for a Boston baseball team that still stands, but had lost the World Series. It was a crushing defeat for Ted, who had gone 0-for-4 in the finale. And, as it turned out, neither Ted (28 years old) nor Stan (25) would ever appear in another World Series game.

*

Ted won the Triple Crown again in 1947, and he and Rogers Hornsby remain the only 2 men to win it twice: He batted. .343, hit 32 home runs and had 114 RBIs. But, again, the Sox didn't win the Pennant. The main reason they won it the year before was that their stars adjusted to civilian life better than the Yankees' stars had, including Joe DiMaggio. In 1947, DiMaggio was back, and he won the MVP by 1 point in the voting over Ted -- because 1 writer, whose name has never been revealed, left Ted off his ballot completely. If he had even listed Ted 10th, Ted would have won it.

In 1948, the Sox tied the Indians for the Pennant, but lost a 1-game Playoff at Fenway. Ted went 1-for-4, but had no RBIs. In 1949, the Sox and Yanks battled for the Pennant all the way to the final weekend. The Sox led the Yanks by 1 game with 2 to go, against each other, at Yankee Stadium. All the Sox had to do was win 1 of the 2. The Yankees won them both, 5-4 and 5-3. Ted went 1-for-3 with a walk in the Saturday game, and 0-for-2 with 2 walks in the Sunday game.

In spite of the Sox not winning the 1949 Pennant, the Yanks didn't have any single player who stood out above the others -- DiMaggio being hurt much of the year, keeping his power stats down -- so Ted got his 2nd MVP. But he had also begun to get a reputation as coming up small in big games. This ignores the fact that, in those 3 end-of-season games in '48 and '49, he did reach base 5 times. But, in those days, you rarely heard the cliche, "A walk is as good as a hit."

The Korean War began in 1950, and, much to Ted's dismay, he was called back to service by the Marines. His last game before rejoining was April 30, 1952, and it was Ted Williams Day at Fenway Park. He received several gifts, including from already-wounded veterans of that war, and it choked him up. He even broke his own taboo about tipping his cap. He still managed to hit a home run in the game.

Captain Williams turned down all offers for a cushy service job, and was soon flying again, in an F9F Panther jet fighter, as a wingman for Major John Glenn -- yes, the future astronaut and U.S. Senator. Glenn said Ted was one of the best pilots he knew, but his wife Annie said he was the most profane man she had ever met.

On February 16, 1953, Williams and Glenn were part of a 35-plane raid against a military training school outside Pyongyang, the North Korean capital. Ted's plane was hit, knocking out his hydraulics and his electrical systems. He managed to get his plane back to its base, and get out, right before it burst into flames.

He ended up flying 39 combat missions, before developing pneumonia, during which an inner ear infection was discovered. This disqualified him from further service, and eventually left him hard of hearing.

Ted remained a lifelong Republican. He hated beatniks, he hated Hippies, and hated feminists. He said he would make one exception when it came to voting Republican: If Glenn would ever have gotten the Democratic nomination for President, he'd vote for him. Glenn only ran for President once, in 1984, and didn't come close.

*

Williams returned to the Red Sox late in the 1953 season, and, despite some nasty injuries, he just kept plugging along. That was also the year the Braves had left Boston for Milwaukee. The Braves had been the sponsors of the Jimmy Fund, run by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute since 1948.

The Institute's founder, Dr. Sidney Farber, turned to the Red Sox, and Williams volunteered to become the face of the Fund, becoming close friends with Farber and raising money all over the country, especially after his retirement as a player gave him more time to do so, until becoming too ill to do so late in life.

In 1956, Ted missed out on another batting title, as Mickey Mantle of the Yankees won the Triple Crown. To this day, Mantle is the last player to lead both Leagues in all 3 categories. However, while Mantle led Williams in batting average, .353 to .345, Williams led Mantle in on-base percentage, .479 to .464.

The 1st time he came to bat in the opener, the A's catcher, Frankie Hayes, told him, "Ted, Mr. Mack told us to pitch to you." As in, we will try to get you out, but we won't try to stop you from getting to .400 by walking you, intentionally or "not."

Ted singled to right in the 2nd inning, hit a home run leading off the 5th, singled to right in the 6th, hit an RBI single to right in the 7th, and reached on an error in the 9th, by the A's 2nd baseman -- Lawrence Columbus "Crash" Davis of Durham, North Carolina, for whom the Kevin Costner character in the movie Bull Durham would be named. So the one time he didn't get a hit, he got on base anyway. Despite a 9-run A's outburst in the 5th inning, the Sox won 12-11.

Ted's batting average was now .404. Even if went 0-for-4 in the nightcap, he would still have finished at .4004 -- but going 0-for-5 would have made him .39956. He played anyway. He singled to right in the 2nd, doubled to center in the 4th, and flew to left in the 7th.

Because Pennsylvania had only legalized professional sporting events on Sunday in 1934, and had a 7:00 PM curfew for them on Sundays, the A's were already up 7-1, and Ted's .400 was secure, it was agreed between the umpires and the managers, Cronin and Mack, that the 2nd game would end after 8 innings, thus denying Ted a 4th at-bat in the game.

He finished the season with 185 hits in 456 at-bats, for a batting average of .405701754, rounded off to .406. He also finished with a league-leading 37 home runs and 120 RBIs -- not surprising, since, for 1940, the Sox had fenced off an area in right field at Fenway Park, and moved the bullpens there, to make it easier for Ted. The pens, and the seats behind them, became known as Williamsburg.

The Sox pitcher in the 2nd game was former A's star Lefty Grove. It was the last appearance of a Hall of Fame career in which he went 300-141.

Joe DiMaggio of the Yankees was awarded the American League MVP for 1941. Red Sox fans, now 3 generations removed, remain angry about this. They say Ted's .406 average was a greater achievement than DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak the same season. They forget that the award is Most Valuable Player, not Most Outstanding Player. Ted's great season did not get the Red Sox the Pennant, finishing 2nd, 17 games behind the Yankees. Joe's great season put the Yankees on a run that led to them winning the World Series.

There would be another MVP controversy in 1942. Ted batted .356, hit 36 home runs, and had 137 RBIs. Each of these led the League, giving him the Triple Crown. But the Sox finished 2nd to the Yankees, and the MVP went to their 2nd baseman, Joe Gordon. How do you deny a Triple Crown winner the MVP? Again: Most Valuable Player, not Most Outstanding Player.

Incidentally, the American League runners on base when Ted hit that walkoff homer in the '41 All-Star Game? Joe DiMaggio and Joe Gordon. (DiMaggio did get a hit in that game, but it didn't count toward his hitting streak, which was then 49 games.)

*

World War II was already underway. In January 1942, Ted was classified 1-A: "Available for unrestricted military service." In other words, the next time there was a draft, Ted could be chosen. A friend reminded Ted that he was now the sole support of his mother, and should appeal. He did, and was reclassified 3-A: "Registrant deferred because of hardship to dependents."

Boston fans, no longer caring that he was a .400 hitter the year before, booed him throughout his Triple Crown season. Opposing fans booed him, too. Quaker Oats dropped him as a spokesman. He had loved their products, but never ate their products again.

Ted had had enough. He joined the Navy Reserve, missed the entire 1943 season on active duty as a pilot trainee, and on May 2, 1944, was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps, as a flight instructor.

Ted didn't see combat in World War II, but would also miss the 1944 and 1945 seasons. He rejoined the Sox for 1946, and hit 3 home runs with 8 RBIs in the 1st game of a doubleheader against the Cleveland Indians. Lou Boudreau, the Indians' manager, invented the infield shift -- in his case, it was called the Boudreau Shift or the Williams Shift. He moved the shortstop (himself) to between 1st and 2nd base, daring Ted, a noted pull hitter, to hit to he opposite field. Did it work? Sort of: Ted grounded to Boudreau twice, but also doubled and walked.

On June 9 of that year, against Fred Hutchinson of the Detroit Tigers -- later to manage the Cincinnati Reds to the 1961 NL Pennant -- hit a drive 502 feet into the center field bleachers. Joe Boucher, a construction engineer from Albany, New York, sat there, and the ball hit him on the head, wrecking his straw hat. The wooden bleachers were replaced by plastic seats in 1976, but the location was noted: It is Section 42, Row 37, Seat 21. In 1984, it was painted red, and it remains "The Red Seat" today.

That year, the All-Star Game was held at Fenway. Ted hit a home run off Kirby Higbe of the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 4th inning. In the 7th, the National League brought in Rip Sewell of the Pittsburgh Pirates. He had a blooper that he called the "eephus pitch." It had been hit, but no one had yet hit it for a home run. Ted did it, and Sewell, in his 4th All-Star Game, was never the same pitcher.

This time, the Red Sox ran away with the Pennant, led by Ted, Doerr, Dom DiMaggio (Joe's brother, also a center fielder), shortstop Johnny Pesky (Cronin was still the manager, but had retired as a player), and pitchers Dave "Boo" Ferriss and Cecil "Tex" Hughson. It was their 1st Pennant since 1918, before selling several players to the Yankees, including Babe Ruth. This time, there was no denying Ted: He batted .342, hit 38 home runs, and had 123 RBIs (oddly, none of these led the AL), and he was an easy choice for MVP.

Then came the World Series. The opposition was the St. Louis Cardinals. Led by the NL's answer to Ted, Stan Musial, the Cards were in their 4th World Series in 6 years, having won in 1942 and 1944, and lost in 1943. But Ted was nursing an elbow injury, and only batted .200, 5-for-25. Stan didn't hit well, either, and neither would end up the big story of the Series.

The Series went to a Game 7 at Sportsman's Park in St. Louis. It was tied 3-3 in the bottom of the 8th. It should be noted that Dom DiMaggio had been injured earlier, and Leon Culberson was now in center field for Boston. Enos Slaughter was on 1st base, and took off with a pitch to Harry Walker, who hit a drive to right-center. Mel Allen, the Yankees' main broadcaster, was covering the Series for NBC despite the Yankees not being in it, and his surviving radio broadcast shows him saying, "Culberson fumbles with the ball momentarily."

Slaughter turned his head, saw this, and realized he could score all the way from 1st. Culberson threw the ball back to the infield. Pesky got it, and... Well, I've seen the film a few times. I can't really say he "hesitated" or "held the ball," as people have been saying for the last 72 years. I don't think it would have mattered, as Slaughter probably would have been safe at the plate anyway. It was 4-3 St. Louis, and that's how it ended.

The Sox had won 104 games, a record for a Boston baseball team that still stands, but had lost the World Series. It was a crushing defeat for Ted, who had gone 0-for-4 in the finale. And, as it turned out, neither Ted (28 years old) nor Stan (25) would ever appear in another World Series game.

*

Ted won the Triple Crown again in 1947, and he and Rogers Hornsby remain the only 2 men to win it twice: He batted. .343, hit 32 home runs and had 114 RBIs. But, again, the Sox didn't win the Pennant. The main reason they won it the year before was that their stars adjusted to civilian life better than the Yankees' stars had, including Joe DiMaggio. In 1947, DiMaggio was back, and he won the MVP by 1 point in the voting over Ted -- because 1 writer, whose name has never been revealed, left Ted off his ballot completely. If he had even listed Ted 10th, Ted would have won it.

In 1948, the Sox tied the Indians for the Pennant, but lost a 1-game Playoff at Fenway. Ted went 1-for-4, but had no RBIs. In 1949, the Sox and Yanks battled for the Pennant all the way to the final weekend. The Sox led the Yanks by 1 game with 2 to go, against each other, at Yankee Stadium. All the Sox had to do was win 1 of the 2. The Yankees won them both, 5-4 and 5-3. Ted went 1-for-3 with a walk in the Saturday game, and 0-for-2 with 2 walks in the Sunday game.

In spite of the Sox not winning the 1949 Pennant, the Yanks didn't have any single player who stood out above the others -- DiMaggio being hurt much of the year, keeping his power stats down -- so Ted got his 2nd MVP. But he had also begun to get a reputation as coming up small in big games. This ignores the fact that, in those 3 end-of-season games in '48 and '49, he did reach base 5 times. But, in those days, you rarely heard the cliche, "A walk is as good as a hit."

The Korean War began in 1950, and, much to Ted's dismay, he was called back to service by the Marines. His last game before rejoining was April 30, 1952, and it was Ted Williams Day at Fenway Park. He received several gifts, including from already-wounded veterans of that war, and it choked him up. He even broke his own taboo about tipping his cap. He still managed to hit a home run in the game.

Captain Williams turned down all offers for a cushy service job, and was soon flying again, in an F9F Panther jet fighter, as a wingman for Major John Glenn -- yes, the future astronaut and U.S. Senator. Glenn said Ted was one of the best pilots he knew, but his wife Annie said he was the most profane man she had ever met.

Major John H. Glenn Jr. and Captain Theodore S. Williams, USMC

On February 16, 1953, Williams and Glenn were part of a 35-plane raid against a military training school outside Pyongyang, the North Korean capital. Ted's plane was hit, knocking out his hydraulics and his electrical systems. He managed to get his plane back to its base, and get out, right before it burst into flames.

He ended up flying 39 combat missions, before developing pneumonia, during which an inner ear infection was discovered. This disqualified him from further service, and eventually left him hard of hearing.

Ted remained a lifelong Republican. He hated beatniks, he hated Hippies, and hated feminists. He said he would make one exception when it came to voting Republican: If Glenn would ever have gotten the Democratic nomination for President, he'd vote for him. Glenn only ran for President once, in 1984, and didn't come close.

*

Williams returned to the Red Sox late in the 1953 season, and, despite some nasty injuries, he just kept plugging along. That was also the year the Braves had left Boston for Milwaukee. The Braves had been the sponsors of the Jimmy Fund, run by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute since 1948.

The Institute's founder, Dr. Sidney Farber, turned to the Red Sox, and Williams volunteered to become the face of the Fund, becoming close friends with Farber and raising money all over the country, especially after his retirement as a player gave him more time to do so, until becoming too ill to do so late in life.

Ted Williams, Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey, and Sidney Farber

In 1956, Ted missed out on another batting title, as Mickey Mantle of the Yankees won the Triple Crown. To this day, Mantle is the last player to lead both Leagues in all 3 categories. However, while Mantle led Williams in batting average, .353 to .345, Williams led Mantle in on-base percentage, .479 to .464.

Ted loved to talk about hitting, and it delighted Ty Cobb in his old age, at a time when he didn't have many friends, that this younger great hitter wanted to talk about hitting with him. Ted and Joe DiMaggio may have had a professional rivalry, but it wasn't personal in the slightest, and they remained friends for the rest of Joe's life. Joe always called Ted the greatest hitter he ever saw, and Ted always called Joe the greatest all-around player he ever saw -- although he also said, "If there was a guy born to play baseball, it was Willie Mays."

But Ted seemed to have a particular interest in Mickey, because there had never been a switch-hitter with Babe Ruth's power lefthanded and Jimmie Foxx's power righthanded. Most previous switch-hitters had been slap hitters, like Pete Rose, and the man Rose succeeded as the all-time hit leader among switch-hitters, Frankie Frisch.

Ted wanted to know Mickey's secret. Before a 1957 game at Yankee Stadium, he asked Mickey all kinds of questions. How do you shift your weight? Which hand do you lead with? Do you prefer swinging up or down? Mickey wasn't flat-out stupid, but he never gave much thought about why he was a good hitter. He just knew he was quick enough to get the bat on the ball, and strong enough to hit it far. He later said Ted had confused him, and he went into a slump, until he decided to stop thinking about hitting and just do it.

That season, just before turning 26, Mickey hit .365, the highest average of his career. But he didn't win the batting title. Ted, who turned 39 near the end of it, hit .388. In 1958, he batted .328, .060 lower than the year before, but good enough to win him the batting title for the 6th and last time -- keeping in mind, he missed the entire seasons in which he turned 25, 26 and 27, and most of the seasons in which he turned 33 and 34.

It also would have helped him if he could have run better. In 19 seasons of play, he stole just 24 bases, hit just 1 inside-the-park home run despite wide-open territory in center and right field at Fenway Park and some other expansive fields in the AL in the 1940s and '50s, and only hit for the cycle once. And he never got 200 hits in a season, topping out at 194 in 1949. He said it himself: "If I coulda run like Mickey Mantle, I'd a-hit .400 every year."

He wasn't known for his defense, either. The Gold Glove award wasn't instituted until late in his career, and it's unlikely he would have won one anyway. But he did become an expert at playing the ricochets off the big left field wall at Fenway, nicknamed the Green Monster.

After retiring, he would teach his successor at that position, Carl Yastrzemski, everything he knew about it, and Yaz became a great fielder -- a better one than Ted, a better runner, and, while not as good a hitter, as good a hitter as just about anybody else. It can be argued that, for all Ted's hitting skill, Yaz was the better all-around player.

Like Ruth, Ted was noted for having great eyesight, supposedly to the point where he could see the stitches on a pitched ball before most players could even see the ball itself. He also had a sensational memory. Long after he retired, he met comedian Billy Crystal, who said, "Ted, I have home movies of you, striking out against Bobby Shantz at Yankee Stadium, 1957, first game of a doubleheader." Ted thought for a moment, and said, "Curveball, low and away."

I looked it up, and the story is true: The Yanks hosted the Sox on the 4th of July in 1957, and in the 1st inning of the 1st game, Shantz struck Ted out, but Bob Grim blew the save by giving up a home run to Mickey Vernon, and the Sox won ,3-2. The Yankees won the nightcap, 4-1, despite Vernon hitting another homer.

In 1959, the Red Sox, the last major league team that hadn't yet integrated, finally did so, with infielder Elijah "Pumpsie" Green. Ted was pleased that it had finally happened. But his own performance that year was unsatisfying: For the 1st time in his career, he failed to bat .300, dropping to .254.

So he decided he couldn't go out like that, and chose to play 1 more year. He batted .316, and made his 19th All-Star Game. On June 17, 1960, he hit the 500th home run of his career, off Wynn Hawkins of the Cleveland Indians, at Municipal Stadium. At this point, only Ruth, Foxx and Mel Ott had gotten to 500.

Ted may also have hit the longest home run at Municipal Stadium. Officially, Luke Easter, who had been a star in the Negro Leagues, hit one 475 feet there. But Mantle may have hit one there that went 490. And I once had a teacher who was from the Cleveland area, and he told me that, in order to keep a reasonable run distance, a chain-link fence was installed that limited center field to 410 feet, whereas the bleacher wall was about 490. The teacher told me Ted was the only player he'd ever seen hit one into the bleachers. When I met him again years later, he stuck to his story.

On September 28, 1960, 19 years to the day after Ted became the last man to bat .400, the Red Sox played their last home game of the season. They had 3 more against the Yankees in New York, but it was already decided that Ted would sit them out.

It was a Wednesday afternoon, the Sox were well out of the race, and their opponents, the Baltimore Orioles, had been in their 1st serious race, but were now out of it as well. The weather wasn't good: Ted later described it as "Lousy day, damp." And Ted's retirement had not been officially announced, so it wasn't known for sure that it would be his finale. So only 10,454 fans came out.

It was 4-2 Baltimore going into the bottom of the 8th. Jack Fisher was pitching in relief of Steve Barber, whose arm might have been sore, or maybe just a little stiff. (Fans of Jim Bouton's book Ball Four will get that joke.) Fisher grooved a pitch, and Ted slammed it into the center field bleachers. It was career home run Number 521. It was also career hit Number 2,654 -- a total which surprises people, to whom it hasn't occurred that Ted Williams is in the 500 Home Run Club, but not the 3,000 Hit Club.

Ted came around to score, and shook the hand of the on-deck hitter, Jim Pagliaroni. (Like Barber, he would be a 1969 Seattle Pilot, and would be mentioned in Ball Four.) And he walked back to the dugout. Sox fans chanted, "We want Ted!" Some fans wondered if he might come out, or even if he'd finally tip his cap.

He did not. John Updike, that most New England of 20th Century upper-crust writers, was there that day. As he put it in "Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu," his classic essay that appeared a few weeks later in The New Yorker, "Gods do not answer letters."

The Sox won the game, 5-4 in the bottom of the 9th, as Fisher gave up a single to Marlan Coughtry, a double to Vic Wertz (see the 1954 World Series), and a walk to Pumpsie Green, completed by Willie Tasby grounding into what looked like a game-ending double play, but 2nd baseman Marv Breeding threw the ball wide of 1st base, scoring Coughtry and Tom Brewer, who had pinch-run for Wertz.

Ted liked to say, "All I ever wanted was to be able to walk down the street, and hear people say, 'There goes the greatest hitter who ever lived.'" And he achieved this dream: Not that he became the greatest hitter who ever lived, but that people said he was.

Is he? In 1995, he published a book, Ted Williams' Hit List, in which he ranked the top 25 hitters ever, based on his own formula. He notably did not include himself in the rankings. His choice for Number 1 was Babe Ruth, whom he met at Fenway in 1943, for a special game to raise money for war bonds.

His lifetime batting average is .344, the highest of any player in the post-1920 Lively Ball Era; Ruth is right behind, at .342. Ted's on-base percentage is .482, the best ever; Ruth is right behind, at .474. Ted's slugging percentage is .634; Ruth is the all-time leader, at .690. Ted's OPS+ is 190, meaning he was 90 percent better at producing runs than the average player of his time; Ruth is the all-time leader, at 206 (106 percent better).

Ted hit 521 home runs, despite missing what amounted to 5 full seasons in his prime, due to 2 wars and a couple of injuries. He hit 36 home runs in 1942, and 38 in 1946, despite playing home games in a park that favored righthanded hitters and hurt lefthanders. (The right field pole at Fenway, then as now, was 302 feet from home plate, but the fence curves, and straightaway right is 380, furthest in the majors.) In 1950, his last full season before going to Korea, Ted hit 30 homers. In 1954, his 1st full season after coming back, 29.

So if we presume that Ted would have averaged 37 home runs over 1943, '44 and '45, and would have hit 30 in '52 and again in '53, minus the 14 he actually hit in those seasons, then we're talking an additional 157 home runs -- giving him 678, just 36 short of what was then the career record, Ruth's 714.

So the 2 greatest hitters who ever lived are Babe Ruth and Ted Williams. Which one was the greatest? Look at the numbers, consider the mitigating factors, and decide for yourself. I say it's Ruth, but is that because he actually was, or is that because I'm a Yankee Fan? How about because Ted said it was, and, if not the greatest hitter who ever lived, certainly, he was the greatest expert on hitting who ever lived.

*

Ted could now relax. He enjoyed fishing, and spent time doing so in Central Florida, to which he'd moved, and on the Miramichi River in the Canadian Province of New Brunswick. I've often compared Ted to Maurice Richard, the great Montreal Canadiens scorer: Both wore Number 9, both were known for their eyes and their burning temper, and both liked to fish. They did fish together a few times, as Ted always appreciated greatness, no matter what the sport, or the line of work.

From 1961 to 1966, he was a Spring Training instructor for the Red Sox. In 1967, Dick Williams (no relation) became the manager, and saw Ted talking to one of the players. When the player said, "Well, Dick wants us to do it this way," and Ted said to do it his way, Dick had Ted thrown out of the camp.

And Sox owner Tom Yawkey, who loved Ted like a son, did nothing about it. That showed the players something: If Dick was willing to defy the team's greatest legend, and could get away with it, then they knew he was the boss. The Sox won the Pennant that season. Ted was not invited back to Spring Training until 1978, by which point Yawkey was dead and Dick was managing his 4th different team.

In 1966, Ted and Casey Stengel were elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, in each case in his 1st year of eligibility. At the induction ceremony at Cooperstown, New York on July 25, Ted said, "I've been a very lucky guy to have worn a baseball uniform, and I hope some day the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, in some way, can be added as a symbol of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren't give a chance."

Eventually, the Hall overseers listened to Ted: In 1971, a special committee was convened, to research the records of Negro League players. Paige became the 1st player they elected. In 1972, Gibson and Buck Leonard joined them. By 1977, 9 players had been elected based on their Negro League play. Over the years, others who had played in the Negro Leagues were elected, but on the basis of their major league performance, including Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays and Hank Aaron.

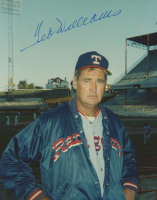

No longer officially affiliated with the Red Sox, in 1969, Ted was offered the job of managing the Washington Senators. He got them to an 86-76 record, the 1st winning record for a Washington-based baseball team in 24 years. Several of the Senators' hitters showed remarkable improvement under Ted's tutelage.

But they dropped off in 1970, and Ted never did get through to the pitchers. He always thought pitchers were dumb, which is hardly the case: Of the ballplayers generally considered intellectuals, a majority of them seem to be pitchers. The team moved to become the Texas Rangers for the 1972 season, and Ted was fired after it, and was never in uniform for another competitive major league game.

You've heard the expression, "(Person's Name) wrote the book on (subject)?" Well, Ted Williams wrote the book on hitting: The Science of Hitting. Dictated to Sports Illustrated writer John Underwood, excerpted in SI in 1968, and published in book form in 1971, it's still the foremost textbook on the subject, and no human being, living or dead, ever knew more about the subject than Ted Williams.

Ted always said, "Hitting a baseball is the hardest thing to do in sports." Of course, while he would talk to anyone about hitting, and go into the minutest detail, whenever anybody asked him, "What's the first thing to know?" he would say, "Get a good pitch to hit." It was what Rogers Hornsby had taught him as a young player.

Ted was married 3 times: To Doris Soule, from 1944 to 1954, and they had a daughter, Barbara Joyce, a.k.a. Bobbi Jo; to Lee Howard, from 1961 to 1967, and they had no children; and to Dolores Wettach, from 1968 to 1972, and they had a son, John Henry, and a daughter, Claudia. From 1973 to 1993, Ted lived with Louise Kaufman at his home in Hernando, Florida, on the Gulf Coast, north of Tampa. He later moved to nearby Citrus Hills.

In 1986, I attended the Hall of Fame's induction ceremony for the first time. I also went in 1988 and 1994. I won't do it again: Cooperstown is too small a town to take on that many visitors at once and remain comfortable. If you want to go to the Hall of Fame, unless it's your favorite player of all time that's going in, go any other time.

It was the first time I got to see Ted in person. He sat next to Ralph Kiner, and kept talking to Kiner all through the speeches, including the one given by his former teammate Bobby Doerr. At one point, Kiner turned to talk to the player next to him, and Ted literally bent his ear, as if to say, "Ralph, I'm not finished, and you're going to listen!"

In his speech, Doerr remembered Ted giving advice, and he refused it, saying he didn't need it. "Okay," Bobby remembered Ted saying, "if you want to be a lousy .280 or .290 hitter, that's your choice!" We all laughed, as .280 is a fairly good average. Bobby finished with a .288 lifetime average, including 223 home runs, a good total for a 2nd baseman in his era.

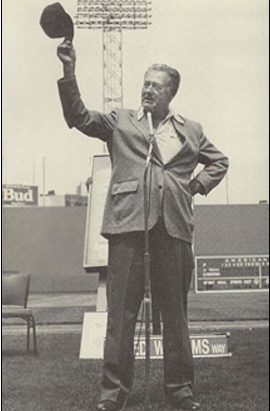

In addition to his election to Cooperstown, Ted had many other honors. In 1954, while still active, he was elected to the San Diego Hall of Champions. In 1984, his Number 9 became the 1st to be retired by the Red Sox. In 1991, the Sox held another Ted Williams Day, in honor of the 50th Anniversary of his .406 season, and he finally tipped his cap to the fans. Lansdowne Street, behind left field, was renamed Ted Williams Way.

Later that year, President George H.W. Bush, a fellow World War II pilot, presented him with the nation's highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 1995, when Ted opened the Ted Williams Museum and Hitters' Hall of Fame in Hernando, he invited Bush, who called him "John Wayne in a baseball uniform." Except Ted really was what Wayne only pretended to be: A great athlete and a genuine war hero. The museum would be moved to the Tampa Bay Rays' Tropicana Field after his death, and is still there.

In 1992, San Diego County renamed its stretch of California State Route 56 the Ted Williams Parkway. In 1995, a new tunnel extending the Massachusetts Turnpike under Boston Harbor to Logan International Airport was named the Ted Williams Tunnel.

In 1999, The Sporting News listed its 100 Greatest Baseball Players, and Ted was ranked 8th, the highest-ranking left fielder. For the sake of perspective, here are the 7 players ranked ahead of him: Babe Ruth, Willie Mays, Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Hank Aaron, Lou Gehrig and Christy Mathewson. That's 4 of the 1st 5 guys elected to the Hall (Ruth, Cobb, Johnson and Mathewson, but not Honus Wagner), a .340 lifetime hitter (Gehrig), and the guys who used to be the top 3 home run hitters ever (Aaron, Ruth and Mays). Although it probably pleased him that only 2 of the guys ahead of him were pitchers.

That year, Ted was named a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team, to be chosen in All-Star-style balloting by the fans. Many of the finalists were introduced before the 1999 All-Star Game, which was held at Fenway Park. After the other finalists were introduced, Ted was driven onto the field in a golf cart, and tipped his cap to the fans.

When the cart stopped, all the greats, current and former, crowded around him, like he was the Pope about to offer blessings. A path had to be cleared for them so he could be eased to a spot in front of the pitcher's mound, where he would throw out the ceremonial first ball to another finalist, former Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk. The man then thought of as the best pure hitter in the game, a modern San Diego Padre, Tony Gwynn, helped steady him so he could properly throw.

When he finished his throw, he was led back to the cart, and the players were still crowding around him. It might have been the first time people had come to a baseball game, and were hoping it wouldn't be played, that the pregame could go on forever.

The fans voted, and, naturally, Ted was elected to the final All-Century Team. Every player elected to it and still living showed up at Turner Field in Atlanta, to be introduced before Game 2 of the World Series between the Braves and the Yankees. Ted tipped his cap again, and Atlanta fans, who never got to see him play (never mind Interleague play, the Braves didn't move to Atlanta until he was already elected to the Hall of Fame), gave him a standing ovation.

It was his last time in a major league ballpark. He'd had a stroke, and his famous vision had already gotten so bad, he couldn't see Fisk from the mound during the Fenway pregame, and was heard to ask, "Where is he?" And he was nearly wheelchair-bound. He had another stroke, and was practically immobile after that. He died on July 5, 2002, at age 83, at Citrus Memorial Hospital in Inverness, Florida.

The tributes flowed. Fenway Park draped the Green Monster with large pictures of Ted's life, and the Sox wore black armbands and black Number 9s on their sleeves for the rest of the season. Every game played that night was preceded by a moment of silence. The All-Star Game was played in Milwaukee 3 days later, and a moment of silence was held.

The less said about what happened to his remains, the better.

Ted has 2 statues outside Fenway Park. One shows him giving his cap to a young fan. The other shows him with Bobby Doerr, Johnny Pesky and Dom DiMaggio, and is named "The Teammates," which was also the title of a book that David Halberstam wrote about them and their friendship.

"The man's a saint!" Bob Costas once said. No, Ted Williams was not a saint. An avenging angel, maybe.

Was he the greatest hitter who ever lived? Does it matter?

Ted Williams was one of the few players who can legitimately be said to have given more to baseball than the sport gave to him. And for that, all fans of all teams should thank him.

Ted wanted to know Mickey's secret. Before a 1957 game at Yankee Stadium, he asked Mickey all kinds of questions. How do you shift your weight? Which hand do you lead with? Do you prefer swinging up or down? Mickey wasn't flat-out stupid, but he never gave much thought about why he was a good hitter. He just knew he was quick enough to get the bat on the ball, and strong enough to hit it far. He later said Ted had confused him, and he went into a slump, until he decided to stop thinking about hitting and just do it.

That season, just before turning 26, Mickey hit .365, the highest average of his career. But he didn't win the batting title. Ted, who turned 39 near the end of it, hit .388. In 1958, he batted .328, .060 lower than the year before, but good enough to win him the batting title for the 6th and last time -- keeping in mind, he missed the entire seasons in which he turned 25, 26 and 27, and most of the seasons in which he turned 33 and 34.

It also would have helped him if he could have run better. In 19 seasons of play, he stole just 24 bases, hit just 1 inside-the-park home run despite wide-open territory in center and right field at Fenway Park and some other expansive fields in the AL in the 1940s and '50s, and only hit for the cycle once. And he never got 200 hits in a season, topping out at 194 in 1949. He said it himself: "If I coulda run like Mickey Mantle, I'd a-hit .400 every year."

He wasn't known for his defense, either. The Gold Glove award wasn't instituted until late in his career, and it's unlikely he would have won one anyway. But he did become an expert at playing the ricochets off the big left field wall at Fenway, nicknamed the Green Monster.

After retiring, he would teach his successor at that position, Carl Yastrzemski, everything he knew about it, and Yaz became a great fielder -- a better one than Ted, a better runner, and, while not as good a hitter, as good a hitter as just about anybody else. It can be argued that, for all Ted's hitting skill, Yaz was the better all-around player.

Like Ruth, Ted was noted for having great eyesight, supposedly to the point where he could see the stitches on a pitched ball before most players could even see the ball itself. He also had a sensational memory. Long after he retired, he met comedian Billy Crystal, who said, "Ted, I have home movies of you, striking out against Bobby Shantz at Yankee Stadium, 1957, first game of a doubleheader." Ted thought for a moment, and said, "Curveball, low and away."

I looked it up, and the story is true: The Yanks hosted the Sox on the 4th of July in 1957, and in the 1st inning of the 1st game, Shantz struck Ted out, but Bob Grim blew the save by giving up a home run to Mickey Vernon, and the Sox won ,3-2. The Yankees won the nightcap, 4-1, despite Vernon hitting another homer.

In 1959, the Red Sox, the last major league team that hadn't yet integrated, finally did so, with infielder Elijah "Pumpsie" Green. Ted was pleased that it had finally happened. But his own performance that year was unsatisfying: For the 1st time in his career, he failed to bat .300, dropping to .254.

So he decided he couldn't go out like that, and chose to play 1 more year. He batted .316, and made his 19th All-Star Game. On June 17, 1960, he hit the 500th home run of his career, off Wynn Hawkins of the Cleveland Indians, at Municipal Stadium. At this point, only Ruth, Foxx and Mel Ott had gotten to 500.

Ted may also have hit the longest home run at Municipal Stadium. Officially, Luke Easter, who had been a star in the Negro Leagues, hit one 475 feet there. But Mantle may have hit one there that went 490. And I once had a teacher who was from the Cleveland area, and he told me that, in order to keep a reasonable run distance, a chain-link fence was installed that limited center field to 410 feet, whereas the bleacher wall was about 490. The teacher told me Ted was the only player he'd ever seen hit one into the bleachers. When I met him again years later, he stuck to his story.

On September 28, 1960, 19 years to the day after Ted became the last man to bat .400, the Red Sox played their last home game of the season. They had 3 more against the Yankees in New York, but it was already decided that Ted would sit them out.

It was a Wednesday afternoon, the Sox were well out of the race, and their opponents, the Baltimore Orioles, had been in their 1st serious race, but were now out of it as well. The weather wasn't good: Ted later described it as "Lousy day, damp." And Ted's retirement had not been officially announced, so it wasn't known for sure that it would be his finale. So only 10,454 fans came out.

It was 4-2 Baltimore going into the bottom of the 8th. Jack Fisher was pitching in relief of Steve Barber, whose arm might have been sore, or maybe just a little stiff. (Fans of Jim Bouton's book Ball Four will get that joke.) Fisher grooved a pitch, and Ted slammed it into the center field bleachers. It was career home run Number 521. It was also career hit Number 2,654 -- a total which surprises people, to whom it hasn't occurred that Ted Williams is in the 500 Home Run Club, but not the 3,000 Hit Club.

Ted came around to score, and shook the hand of the on-deck hitter, Jim Pagliaroni. (Like Barber, he would be a 1969 Seattle Pilot, and would be mentioned in Ball Four.) And he walked back to the dugout. Sox fans chanted, "We want Ted!" Some fans wondered if he might come out, or even if he'd finally tip his cap.

He did not. John Updike, that most New England of 20th Century upper-crust writers, was there that day. As he put it in "Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu," his classic essay that appeared a few weeks later in The New Yorker, "Gods do not answer letters."

The Sox won the game, 5-4 in the bottom of the 9th, as Fisher gave up a single to Marlan Coughtry, a double to Vic Wertz (see the 1954 World Series), and a walk to Pumpsie Green, completed by Willie Tasby grounding into what looked like a game-ending double play, but 2nd baseman Marv Breeding threw the ball wide of 1st base, scoring Coughtry and Tom Brewer, who had pinch-run for Wertz.

Ted liked to say, "All I ever wanted was to be able to walk down the street, and hear people say, 'There goes the greatest hitter who ever lived.'" And he achieved this dream: Not that he became the greatest hitter who ever lived, but that people said he was.

Is he? In 1995, he published a book, Ted Williams' Hit List, in which he ranked the top 25 hitters ever, based on his own formula. He notably did not include himself in the rankings. His choice for Number 1 was Babe Ruth, whom he met at Fenway in 1943, for a special game to raise money for war bonds.

Why Ted was wearing a Red Sox road jersey,

and the Babe the Yankees' home Pinstripes, I don't know.

His lifetime batting average is .344, the highest of any player in the post-1920 Lively Ball Era; Ruth is right behind, at .342. Ted's on-base percentage is .482, the best ever; Ruth is right behind, at .474. Ted's slugging percentage is .634; Ruth is the all-time leader, at .690. Ted's OPS+ is 190, meaning he was 90 percent better at producing runs than the average player of his time; Ruth is the all-time leader, at 206 (106 percent better).

Ted hit 521 home runs, despite missing what amounted to 5 full seasons in his prime, due to 2 wars and a couple of injuries. He hit 36 home runs in 1942, and 38 in 1946, despite playing home games in a park that favored righthanded hitters and hurt lefthanders. (The right field pole at Fenway, then as now, was 302 feet from home plate, but the fence curves, and straightaway right is 380, furthest in the majors.) In 1950, his last full season before going to Korea, Ted hit 30 homers. In 1954, his 1st full season after coming back, 29.

So if we presume that Ted would have averaged 37 home runs over 1943, '44 and '45, and would have hit 30 in '52 and again in '53, minus the 14 he actually hit in those seasons, then we're talking an additional 157 home runs -- giving him 678, just 36 short of what was then the career record, Ruth's 714.

So the 2 greatest hitters who ever lived are Babe Ruth and Ted Williams. Which one was the greatest? Look at the numbers, consider the mitigating factors, and decide for yourself. I say it's Ruth, but is that because he actually was, or is that because I'm a Yankee Fan? How about because Ted said it was, and, if not the greatest hitter who ever lived, certainly, he was the greatest expert on hitting who ever lived.

*

Ted could now relax. He enjoyed fishing, and spent time doing so in Central Florida, to which he'd moved, and on the Miramichi River in the Canadian Province of New Brunswick. I've often compared Ted to Maurice Richard, the great Montreal Canadiens scorer: Both wore Number 9, both were known for their eyes and their burning temper, and both liked to fish. They did fish together a few times, as Ted always appreciated greatness, no matter what the sport, or the line of work.

From 1961 to 1966, he was a Spring Training instructor for the Red Sox. In 1967, Dick Williams (no relation) became the manager, and saw Ted talking to one of the players. When the player said, "Well, Dick wants us to do it this way," and Ted said to do it his way, Dick had Ted thrown out of the camp.

And Sox owner Tom Yawkey, who loved Ted like a son, did nothing about it. That showed the players something: If Dick was willing to defy the team's greatest legend, and could get away with it, then they knew he was the boss. The Sox won the Pennant that season. Ted was not invited back to Spring Training until 1978, by which point Yawkey was dead and Dick was managing his 4th different team.

In 1966, Ted and Casey Stengel were elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, in each case in his 1st year of eligibility. At the induction ceremony at Cooperstown, New York on July 25, Ted said, "I've been a very lucky guy to have worn a baseball uniform, and I hope some day the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, in some way, can be added as a symbol of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren't give a chance."

Eventually, the Hall overseers listened to Ted: In 1971, a special committee was convened, to research the records of Negro League players. Paige became the 1st player they elected. In 1972, Gibson and Buck Leonard joined them. By 1977, 9 players had been elected based on their Negro League play. Over the years, others who had played in the Negro Leagues were elected, but on the basis of their major league performance, including Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays and Hank Aaron.

No longer officially affiliated with the Red Sox, in 1969, Ted was offered the job of managing the Washington Senators. He got them to an 86-76 record, the 1st winning record for a Washington-based baseball team in 24 years. Several of the Senators' hitters showed remarkable improvement under Ted's tutelage.

It's not Johnny Unitas with the San Diego Chargers,

or Joe Namath with the Los Angeles Rams,

but it looks strange enough.

But they dropped off in 1970, and Ted never did get through to the pitchers. He always thought pitchers were dumb, which is hardly the case: Of the ballplayers generally considered intellectuals, a majority of them seem to be pitchers. The team moved to become the Texas Rangers for the 1972 season, and Ted was fired after it, and was never in uniform for another competitive major league game.

Even stranger.

You've heard the expression, "(Person's Name) wrote the book on (subject)?" Well, Ted Williams wrote the book on hitting: The Science of Hitting. Dictated to Sports Illustrated writer John Underwood, excerpted in SI in 1968, and published in book form in 1971, it's still the foremost textbook on the subject, and no human being, living or dead, ever knew more about the subject than Ted Williams.

A first edition, with the famed 77-ball chart of how well

Ted hit balls at each spot of his strike zone,

which now rests in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

As you can see, and as Bobby Shantz and few others figured out,

the way to pitch Ted was, "Curveball, low and away."

Ted always said, "Hitting a baseball is the hardest thing to do in sports." Of course, while he would talk to anyone about hitting, and go into the minutest detail, whenever anybody asked him, "What's the first thing to know?" he would say, "Get a good pitch to hit." It was what Rogers Hornsby had taught him as a young player.

Ted was married 3 times: To Doris Soule, from 1944 to 1954, and they had a daughter, Barbara Joyce, a.k.a. Bobbi Jo; to Lee Howard, from 1961 to 1967, and they had no children; and to Dolores Wettach, from 1968 to 1972, and they had a son, John Henry, and a daughter, Claudia. From 1973 to 1993, Ted lived with Louise Kaufman at his home in Hernando, Florida, on the Gulf Coast, north of Tampa. He later moved to nearby Citrus Hills.

In 1986, I attended the Hall of Fame's induction ceremony for the first time. I also went in 1988 and 1994. I won't do it again: Cooperstown is too small a town to take on that many visitors at once and remain comfortable. If you want to go to the Hall of Fame, unless it's your favorite player of all time that's going in, go any other time.

It was the first time I got to see Ted in person. He sat next to Ralph Kiner, and kept talking to Kiner all through the speeches, including the one given by his former teammate Bobby Doerr. At one point, Kiner turned to talk to the player next to him, and Ted literally bent his ear, as if to say, "Ralph, I'm not finished, and you're going to listen!"

In his speech, Doerr remembered Ted giving advice, and he refused it, saying he didn't need it. "Okay," Bobby remembered Ted saying, "if you want to be a lousy .280 or .290 hitter, that's your choice!" We all laughed, as .280 is a fairly good average. Bobby finished with a .288 lifetime average, including 223 home runs, a good total for a 2nd baseman in his era.

Bobby Orr, Ted Williams and Larry Bird,

brought together by Boston sportscaster Bob Lobel,

Sports Final, WBZ-Channel 4, December 7, 1992.

It happened to be Bird's 36th birthday.

Williams and Orr had fished together a few times.

In addition to his election to Cooperstown, Ted had many other honors. In 1954, while still active, he was elected to the San Diego Hall of Champions. In 1984, his Number 9 became the 1st to be retired by the Red Sox. In 1991, the Sox held another Ted Williams Day, in honor of the 50th Anniversary of his .406 season, and he finally tipped his cap to the fans. Lansdowne Street, behind left field, was renamed Ted Williams Way.

Later that year, President George H.W. Bush, a fellow World War II pilot, presented him with the nation's highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 1995, when Ted opened the Ted Williams Museum and Hitters' Hall of Fame in Hernando, he invited Bush, who called him "John Wayne in a baseball uniform." Except Ted really was what Wayne only pretended to be: A great athlete and a genuine war hero. The museum would be moved to the Tampa Bay Rays' Tropicana Field after his death, and is still there.

In 1992, San Diego County renamed its stretch of California State Route 56 the Ted Williams Parkway. In 1995, a new tunnel extending the Massachusetts Turnpike under Boston Harbor to Logan International Airport was named the Ted Williams Tunnel.

In 1999, The Sporting News listed its 100 Greatest Baseball Players, and Ted was ranked 8th, the highest-ranking left fielder. For the sake of perspective, here are the 7 players ranked ahead of him: Babe Ruth, Willie Mays, Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Hank Aaron, Lou Gehrig and Christy Mathewson. That's 4 of the 1st 5 guys elected to the Hall (Ruth, Cobb, Johnson and Mathewson, but not Honus Wagner), a .340 lifetime hitter (Gehrig), and the guys who used to be the top 3 home run hitters ever (Aaron, Ruth and Mays). Although it probably pleased him that only 2 of the guys ahead of him were pitchers.

That year, Ted was named a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team, to be chosen in All-Star-style balloting by the fans. Many of the finalists were introduced before the 1999 All-Star Game, which was held at Fenway Park. After the other finalists were introduced, Ted was driven onto the field in a golf cart, and tipped his cap to the fans.

When the cart stopped, all the greats, current and former, crowded around him, like he was the Pope about to offer blessings. A path had to be cleared for them so he could be eased to a spot in front of the pitcher's mound, where he would throw out the ceremonial first ball to another finalist, former Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk. The man then thought of as the best pure hitter in the game, a modern San Diego Padre, Tony Gwynn, helped steady him so he could properly throw.

When he finished his throw, he was led back to the cart, and the players were still crowding around him. It might have been the first time people had come to a baseball game, and were hoping it wouldn't be played, that the pregame could go on forever.

The fans voted, and, naturally, Ted was elected to the final All-Century Team. Every player elected to it and still living showed up at Turner Field in Atlanta, to be introduced before Game 2 of the World Series between the Braves and the Yankees. Ted tipped his cap again, and Atlanta fans, who never got to see him play (never mind Interleague play, the Braves didn't move to Atlanta until he was already elected to the Hall of Fame), gave him a standing ovation.

It was his last time in a major league ballpark. He'd had a stroke, and his famous vision had already gotten so bad, he couldn't see Fisk from the mound during the Fenway pregame, and was heard to ask, "Where is he?" And he was nearly wheelchair-bound. He had another stroke, and was practically immobile after that. He died on July 5, 2002, at age 83, at Citrus Memorial Hospital in Inverness, Florida.

The tributes flowed. Fenway Park draped the Green Monster with large pictures of Ted's life, and the Sox wore black armbands and black Number 9s on their sleeves for the rest of the season. Every game played that night was preceded by a moment of silence. The All-Star Game was played in Milwaukee 3 days later, and a moment of silence was held.

The less said about what happened to his remains, the better.

Ted has 2 statues outside Fenway Park. One shows him giving his cap to a young fan. The other shows him with Bobby Doerr, Johnny Pesky and Dom DiMaggio, and is named "The Teammates," which was also the title of a book that David Halberstam wrote about them and their friendship.

Left to right: Johnny, Bobby, Ted, Dom

"The man's a saint!" Bob Costas once said. No, Ted Williams was not a saint. An avenging angel, maybe.

Was he the greatest hitter who ever lived? Does it matter?

Ted Williams was one of the few players who can legitimately be said to have given more to baseball than the sport gave to him. And for that, all fans of all teams should thank him.