Just when we thought that 2021 would let us have nice things...

Henry Louis Aaron was born on February 5, 1934 in Mobile, Alabama. His parents, Herbert and Estella, could not afford baseball equipment, so he used sticks as bats, and bottle caps as balls. He attended Central High School, but it did not have a baseball team. He transferred to Allen Institute, but they didn't have one, either. So he signed with a semipro team, the Mobile Black Bears.

His timing was right: He was 13 years old when Jackie Robinson reintegrated what we would now call Major League Baseball, with the Brooklyn Dodgers. When he was 15, he got a tryout with the Dodgers, but did not get a pro contract. He remained with the Black Bears, earning $3.00 per game.

Like Mickey Mantle, he began his professional career as a shortstop, but his fielding was such that he was switched to the outfield. In between, he was also tried at 2nd base. In 1952, he was signed by the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League, earning $200 a month.

Despite growing up in segregated Alabama, he later said that he didn't experience real racism until he was played for the Clowns against the Homestead Grays in Washington, D.C. He was 18 years old:

We had breakfast while we were waiting for the rain to stop, and I can still envision sitting with the Clowns in a restaurant behind Griffith Stadium and hearing them break all the plates in the kitchen after we finished eating. What a horrible sound.

Even as a kid, the irony of it hit me: here we were in the capital in the land of freedom and equality, and they had to destroy the plates that had touched the forks that had been in the mouths of black men. If dogs had eaten off those plates, they'd have washed them.

He was soon noticed by the New York Giants, who already had former Negro League stars Willie Mays and Monte Irvin; and the Boston Braves, who had integrated with 1948 National League Rookie of the Year Sam Jethroe.

"I had the Giants' contract in my hand," Aaron would later say, "but the Braves offered $50 a month more. That's the only thing that kept Willie Mays and me from being teammates: Fifty dollars." On such hinge moments does the history of a sport sometimes hang in the balance. On June 12, 1952, the Braves paid the Clowns $10,000 for his contract.

He spent the rest of the 1952 season with the Eau Claire Bears in the Class C Northern League -- roughly Class A ball by today's standards. Even in a Northern State like Wisconsin, he faced racism, and he wrote to his older brother, Herbert Aaron Jr., about it. Herbert wrote back, telling him not to quit, that the opportunity was too good to give up. Herbert was right: Henry (it would be a few years before he was commonly called "Hank") batted .336 and was named the league's Rookie of the Year.

If the Braves had hung on in Boston for just a little longer, they would have had a team with Hank Aaron, Warren Spahn, Eddie Matthews, Joe Adcock, Del Crandall, Billy Bruton and Wes Covington. They might have done big things in Boston. They might have convinced Tom Yawkey, who had no real ties to Boston, to move the Red Sox to another city, making the Braves, who had been the most successful American sports franchise of the 19th Century, the MLB that survived in the Hub City.

And, if the Braves had, in the mid-to-late 1950s or early 1960s, built a new ballpark to replace Braves Field, it might have been friendly to hitters, and Aaron might have notched his most notable achievement in 1973, instead of everyone waiting around for an additional off-season for him to do it.

But none of that happened. For the 1953 season, the Braves moved to Milwaukee, where they had their top farm team, the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association. Also that season, they assigned the 19-year-old Henry Aaron to the Jacksonville Tars of the Class A South Atlantic League, a.k.a. the Sally League. ("Tar" is not a racist reference: It is an old name for a sailor. A team in Norfolk, Virginia was also named the Tars.)

Jacksonville is in northeastern Florida, on the State Line with Georgia. This is not Miami, not South Florida, not the haven for elderly Jews, Italians and Cubans. This is the eastern edge of the Florida Panhandle, the "Redneck Riviera." This is home to "Florida Man." And, even today, this is a racist place.

The 1953 Tars would be Florida's 1st racially-integrated minor-league baseball team. Their manager was Ben Geraghty, a native of Jersey City, and he would take his team into restaurant after restaurant until he find one that would serve them. Aaron would call Geraghty the greatest manager who ever lived. Sadly, he was in poor health, and died in 1963, only 51.

In that 1953 season, Aaron survived the torrents of bigotry, leading the SAL in batting average (.362), runs, hits, doubles, runs batted in and total bases -- everything, a sportswriter said, except hotel accommodations. He won the League's Most Valuable Player award, and the Tars won the Pennant.

That year, Henry also met Barbara Lucas. They married after the season, and had 5 children: Sons Gary, Lary and Hank Jr., and daughters Dorinda and Gaie. They split up in 1971. In 1973, in the off-season when he was in the eye of the storm, he married an early female sportswriter, Billye Williams, and they had a daughter named Ceci.

*

Invited to Spring Training in 1954, Braves manager Charlie Grimm had a tough choice to make. Henry was hitting so well that it looked like he should make the major league team, but he wasn't fielding like a major leaguer. Would he make the team as a 2nd baseman? Would he make it as an outfielder? Would he not make it at all?

On March 13, Bobby Thomson, the 1951 New York Giant hero who was a recent acquisition by the Braves, and seemed set to be their starting left fielder, broke his ankle in a preseason exhibition game. That took the decision out of Grimm's hands: Henry Aaron would be the Braves' starting left fielder.

On April 13, 1954, he made his major league debut, at Crosley Field in Cincinnati. Wearing Number 5, he played left field and batted 5th. In the 1st inning, batting against Bud Podbelian, he popped up to shortstop Roy McMillan, who then turned an inning-ending double play. Podbelian had to leave the game, and was replaced by Joe Nuxhall. In the 3rd inning, he grounded to 3rd base. In the 4th, he popped up to 2nd. In the 7th, and again in the 8th, he flew out to right. He went 0-for-5, and the Braves lost to the Cincinnati Reds, 9-8. Hank was the last living man who had played in that game.

Two days later, at Milwaukee County Stadium, he got his 1st major league hit, a double off Vic Raschi, a former Yankee ace now pitching for the St. Louis Cardinals. On April 23, at Sportsman's Park in St. Louis, again off Raschi, he hit his 1st major league home run.

Just 20 years old, he would bat .280, with 13 home runs and 69 RBIs, despite breaking his own ankle on September 5 to end his season. He finished 4th in the NL Rookie of the Year voting, behind Wally Moon of the Cardinals, Ernie Banks of the Chicago Cubs, and his Braves teammate Gene Conley.

For the 1955 season, he switched to Number 44, and was moved to right field. Don Davidson, the Braves' public relations director, began listing him as "Hank" in official releases. From then on, "Henry" and "Hank" would be used interchangeably. He even had competing nicknames: "Bad Henry" (being bad for pitchers to face) and "Hammerin' Hank" (a name previously given to Detroit Tigers Hall-of-Famer Hank Greenberg).

In 1955, he batted .300 for the 1st time, .314, and led the NL with 37 doubles. He made his 1st All-Star Game, on his home field in Milwaukee. (Stan Musial won it for the NL with a home run in the 12th inning, and Conley ended up as the winning pitcher.) In 1956, he won his 1st batting title with a .328 average, and also led the NL in hits (an even 200, his 1st time getting that many), doubles and total bases. The Braves finished just 1 game behind the Brooklyn Dodgers for the Pennant.

In 1957, the Braves won their 1st Pennant since 1914, when they were in Boston. They clinched on September 23, with Aaron hitting a game-winning home run in the bottom of the 11th, off Billy Muffett of the Cardinals. Aaron was also named the NL's Most Valuable Player. It would be his only MVP award.

They faced the Yankees in the World Series. Hank later said that Yankee Stadium intimidated them, but that the Yankees did not. He was happy to pose with Mantle for the newspapers and the newsreels. But when he came up to bat, catcher Yogi Berra, who enjoyed talking to hitters in the hopes of unsettling him, told Hank he was holding the bat with the trademark facing the pitcher, which makes it easier to break the bat. "Hank said, Didn't come up here to read. Came up here to hit."

The Braves won the Series in 7 games, clinching at Yankee Stadium. They won the Pennant again in 1958, but lost the Series to the Yankees. In 1959, Hank won another batting title, but the Braves finished in a tie for the Pennant with the Dodgers, who had moved to Los Angeles, and the Dodgers won the subsequent Playoff. As it turned out, that would be the closest Hank would get to another World Series.

The Gold Glove Award for fielding excellence was first given in 1958, and Hank won it for National League right fielders in each of its 1st 3 seasons. He would never win another, through no fault of his own, as Frank Robinson and Roberto Clemente would dominate that award.

In the Winter of 1960, Hank appeared on the TV show Home Run Derby. He was the show's most successful player, winning 6 games, beating, in succession, Ken Boyer of the Cardinals, Jim Lemon of the Washington Senators, his Braves teammate Eddie Mathews, Al Kaline of the Detroit Tigers, Duke Snider of the Dodgers and Bob Allison of the Senators, before losing to Wally Post, the Reds slugger then with the Philadelphia Phillies. With the show's prizes, including bonuses for consecutive homers, he won $13,500. He had been paid $35,000 the season before.

By this point, he was already regarded as one of the best all-around players in the game, along with Mantle and Mays. Most observers, including Home Run Derby host Mark Scott, took note of how he was then a bit skinny, but had "quick wrists." At that point, if you had told longtime baseball people that he would end up with over 3,000 hits, they probably would have believed it. If you had told them he would hit 500 home runs, they might have believed that.

But if you had told them that Henry Aaron would be the man to break Babe Ruth's career record of 714 home runs, that would have never occurred to them. Most people thought that, if it ever happened, it would be either Mantle or Mays who did it.

Former Giants pitcher Sal Maglie, known for his great curveball, was then in his early days as a pitching coach. He recommended throwing Hank low curves: "He's going to swing, and he'll go after almost anything. And he'll hit almost anything, so you have to be careful."

Before a game with the Braves, the Giants were going over the opposing hitters, trying to figure out how to pitch to them. When Aaron was mentioned, there was an unsteady silence, until somebody said, "Make sure there's no one on when he hits it out."

"The pitcher has got only a ball," Hank himself said. "I’ve got a bat. So the percentage in weapons is in my favor, and I let the fellow with the ball do the fretting."

*

Also in the Winter of 1960, he campaigned for Senator John F. Kennedy in the Wisconsin Primary. So did Green Bay Packer coach Vince Lombardi. Lombardi was born and raised Catholic, while Aaron and his wife Barbara had recently converted.

On June 24, JFK wrote him a letter, saying, "I hope to see you push that average up over the .300 mark now that the hot weather is here." (Maybe if the Braves had stayed in Kennedy's native Boston, they would have been closer friends. But without being in Milwaukee, maybe Hank wouldn't have campaigned in that Wisconsin Primary, and Kennedy wouldn't have been nominated.)

On June 18, 1962, against the Mets, Hank hit a home run into the center field bleachers at the Polo

Grounds. He became the 3rd and last player to do it. Lou Brock had done it just the day before, and his Braves teammate Adcock had done it in 1953.

The Braves remained in contention in the early 1960s, but didn't win another Pennant. The novelty of Milwaukee being in the major leagues began to wear off. And the arrival of the Minnesota Twins in 1961 took the States of Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota, and even westernmost Wisconsin, out of what would now be called the Braves' "market." Attendance dropped.

This, despite the Braves having Hank, who led the NL in doubles and total bases in 1961; slugging percentage, runs scored, total bases, homers and RBIs in 1963; and doubles again in 1965. That would be their last season in Milwaukee: Team owner Bill Bartholomay moved them to Atlanta.

With the Houston Astros representing Texas in the major leagues, the Braves would be a regional team for the rest of the South. While Charlotte, Nashville and New Orleans now have NFL teams; Charlotte, Memphis and New Orleans have NBA teams; and Raleigh and Nashville have NHL teams, Atlanta remains the only Southern city, outside of Texas and Florida, to have an MLB team.

Mayor William Hartsfield, knowing the reputation that Birmingham, Alabama was getting outside the South, knew he had to grow Atlanta by appealing to the North. He called it "The City Too Busy to Hate," brought in major companies to establish new headquarters there, built the airport that now bears his name, and built Atlanta Stadium in 1965, renamed Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium in 1975. In its 1st year, it hosted the Beatles. The following year, it became home to the Braves and an NFL expansion team, the Atlanta Falcons.

But Spahn had been traded, and 1966 was the last season with the Braves for Mathews, leaving Aaron, a black man, as the biggest star on the South's team. This could have been a problem, and may have held down the Braves' attendance there.

As teammates from 1954 to 1966, Aaron and Mathews combined for 863 home runs. That remains an all-time record for teammates. (Mathews would close his career with 512 home runs.) Hank's brother Tommie Aaron would also play for the Braves on and off from 1962 (in Milwaukee) to 1971 (in Atlanta). He hit just 13 homers in his career, but it was enough to make the Aaron's the all-time home-run-hitting brother combination.

Hank led the NL in homers and RBIs again in 1966. He led it in homers, slugging, runs and total bases in 1967. Moving from Milwaukee County Stadium to Atlanta Stadium helped his hitting: Atlanta had the highest elevation of any major league city until Denver got the Colorado Rockies in 1993, and the ball flew out of the stadium. It became known as "The Launching Pad."

The greatest pitcher of all time? Some people say it was Sandy Koufax. The greatest hitter Koufax ever faced? He said it was Hank Aaron. Against Koufax, he batted .372 with 7 home runs. In fact, Hank hit 72 home runs off pitchers in the Hall of Fame. Next-best is Mays with 62.

He played in several notable games: Koufax's major league debut, on June 24, 1955, an 8-2 Braves win over the Dodgers at Ebbets Field; the game where Harvey Haddix pitched 12 perfect innings, and then lost to the Braves in the 13th inning, 1-0, at County Stadium; Joe Torre's 1st game, on September 25, 1960, a 4-2 Braves win over the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field; the end of the Phillies' 23-game losing streak, a 20th Century record, on August 20, 1961, a 7-4 win over the Braves at County Stadium; the 16-inning scoreless duel between Spahn and Juan Marichal, which the Giants won 1-0, on a Mays homer, on July 2, 1963 at Candlestick Park; Yogi Berra's last game, on May 9, 1965, a 5-4 Mets win over the Braves at County Stadium; Nolan Ryan's 1st game, on September 11, 1966, an 8-3 win over the Mets at Shea Stadium; and the doubleheader in which the San Diego Padres' Nate Colbert hit 5 home runs, on August 1, 1972, which the Padres swept from the Braves, 9-0 and 11-7.

*

On July 14, 1968, at Atlanta Stadium, against Mike McCormick of the San Francisco Giants, Hank hit the 500th home run of his career. He was only the 8th player to reach that milestone, following Babe Ruth, Jimmie Foxx, Mel Ott, Ted Williams, Mays, Mantle, and Mathews.

He was only 34 years old, showed no sign of slowing down, and was playing in a great hitter's park. Mantle was succumbing to his injuries, and would retire just before the next season, with 536 home runs. Mays had surpassed Mantle, and had also surpassed Ott (511) to become the NL's all-time home run leader. He had surpassed Williams (521) and Foxx (534). With Mantle having fallen away, the consensus was that, if any player would surpass Ruth's all-time record of 714, it was going to be Mays. Suddenly, baseball fans had to reckon with the possibility that it could be Aaron. He ended the season with 510.

And people had hardly noticed until then. I've called LL Cool J "the Hank Aaron of Rap": He's not the most-talked-about rapper of all time, but he's done it so well for longer than just about anybody, so people just don't realize how good he's been.

In 1969, the Divisional Play Era began. The Braves and the Reds were put into the NL's Western Division, and the Cubs and the Cardinals into the Eastern Division, despite Atlanta and Cincinnati being further east than Chicago and St. Louis. The Braves won the Division, as Hank matched his uniform number with 44 home runs in a season for the 4th time, including his 537th, to pass Mantle; and again led the NL in total bases. But the Braves were swept by the New York Mets in the 1st-ever NL Championship Series. It would be Hank's last postseason appearance. He now had 554 home runs.

On May 17, 1970, at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, off Wayne Simpson, he singled home Félix Millán. It was his 3,000th career hit. It made him the 1st player to reach both 3,000 hits and 500 home runs, beating Mays to the dual distinction by 2 months. Also in that game, he hit a home run, and singled and scored the winning run in the 10th inning. He finished the season with 592 home runs.

In 1971, Hank tied Mathews' franchise record with 47 home runs, including the 600th of his career, on April 27, off Gaylord Perry of the Giants at Atlanta Stadium. He finished the season with 641. It wasn't enough to lead the NL, as Willie Stargell of the Pittsburgh Pirates hit 48. But it was a career high: For all the homers he hit, he never hit 50 in a season. And he only shared the team record, until Andruw Jones hit 51 in 2005.

In 1972, Mathews was named the Braves' manager, and the team switched to a weird new uniform, with a lower-case A on their caps and the blue and red cornstalks on the sleeves. (It was the 1970s.) Hank surpassed Musial's record of 6,134 total bases, joined Ruth as the only players with 2,000 career RBIs, and, on June 11, hit the 649th home run of his career, surpassing Mays for 2nd all-time. Mays would retire the next season, with 660.

Ernie Harwell, broadcaster for the Detroit Tigers, but a Georgia native who had worked for an Atlanta newspaper and got his broadcasting start with the city's former minor-league team, the Atlanta Crackers, was also a published songwriter, and wrote "Move Over Babe, Here Comes Henry."

When the 1972 season ended, Henry, or Hank (he answered to both), had 673. He would turn 39 in the off-season, but, except for his ankle injury as a rookie, he had never been seriously hurt. It was no longer a question of, "Can he do it?" Only of, "When?" and "Will anything short of a career-ending injury stop him?"

In 1973, it looked like no pitcher could stop him. He just kept slugging away. As America dealt with the fallout from the end of its role in the Vietnam War, and the drip-drip-drip of revelations of the Watergate scandal then engulfing President Richard Nixon, the chase for the record was a welcome distraction for baseball fans.

On June 9, Secretariat won the Belmont Stakes by a stunning 31 lengths, becoming the 1st horse in 25 years to win thoroughbred racing's Triple Crown. Once the excitement from that began to fade, there was nothing for a sports fan whose team wasn't in the Pennant race to watch other than Hank Aaron getting to 680, 685, 690... On July 21, at Atlanta Stadium against Ken Brett of the Phillies (whose brother George would soon make his major league debut for the Kansas City Royals), Hank tallied Number 700.

The attention mounted. Soon, he was getting more mail than anybody in America, except Nixon himself. But, as with Nixon, some of it was hate mail. And some of it was terribly racist in nature. I won't quote any of it here. But at a time when civil rights legislation was an established fact of life, black people were leading the way in popular music, and black directors were making some of the most popular movies (including "blaxploitation films" like Shaft, Superfly, Blacula, Foxy Brown, Cleopatra Jones and Uptown Saturday Night), some people were furious that a black man was in position to break Ruth's record.

It got to the point where Charles Schulz, the cartoonist behind Peanuts, satirized it by having Snoopy approach the record, and get hate mail over it:

Even some people who didn't seem to be racist didn't want the record broken, saying that Hank getting to 715 would make people "forget" Ruth. "I don't want them to forget Babe Ruth," Hank said. "I just want them to remember me."

It didn't help that Ruth was dead. He would have been 66 years old when Roger Maris of the Yankees broke the single-season record of 60 with his "61 in '61." He had a very unhealthy lifestyle, but had he taken care of himself, it wouldn't have been impossible for him to still be alive at age 78 in 1973, and offered his support. His widow, Claire Ruth, didn't want either 60 or 714 to fall. But it's easy to imagine a still-living Bambino saying, on either occasion, "This is good for baseball. And anything that's good for baseball is good for me."

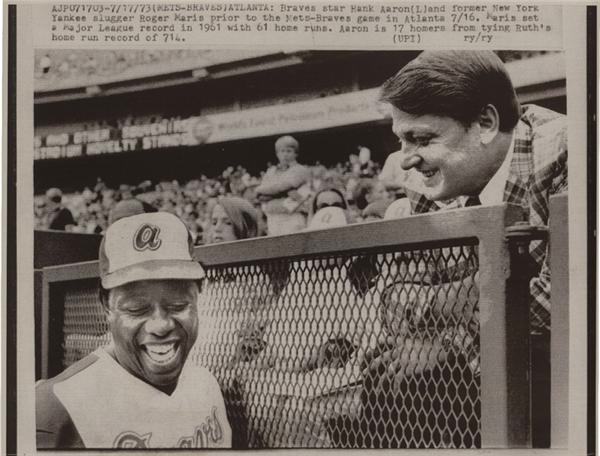

And with Jackie Robinson having died the preceding October, Maris, who got 100 men's shares of hate mail and phone calls, was the one man who had any idea of what Hank was going through. Now retired and running a beer distributorship in Gainesville, Florida, he made the 330-mile trip to Atlanta to meet Hank on July 16.

This photo is rare not just because it shows the two "home run kings" together,

but because it shows Roger Maris without his famous crew cut.

One thing Maris did not have to deal with in 1961 was racism. But he was mocked as "a .270 hitter." Aaron finished the 1973 season with a .301 average. Plagued by injuries, Maris retired in 1968, only 34 years old, with 275 home runs. Aaron was still going strong, in spite of the stress.

Hank realized he had another advantage. If Roger had fallen short, he would have had to start all over again the next year. If Hank fell short in 1973, he would still be able to break the record the next year. There was no pressure coming from the calendar. (It was coming from the haters.)

But fans weren't coming out to see his march to the record. The Braves drew only 800,655 fans, just 9,885 per game. "The City Too Busy to Hate" may also have been too busy to care. The Braves being 76-85, in 5th place, may have had something to do with that. But on September 29, the next-to-last day of the season, home to the Houston Astros, Hank hit Number 713 off Jerry Reuss. The Braves won, 7-0. Attendance: 17,836.

Suddenly, people realized that, in the season finale, if Hank hit 2 home runs, hardly impossible, he would break the record. If he hit 1, he would tie it. And so, on September 30, 40,517 people came out -- still well short of the listed capacity of 52,007. Hank had an RBI single in the 1st. He singled again in the 4th. He singled again in the 6th. Three hits, a successful game by almost anybody's standard. But now, it was almost impossible to break the record on this day. And he flew out in the 8th. The Astros won, 5-3.

The season was over, and Hank Aaron had 713 career home runs. And so began a long wait. And the threats kept coming in. There was even a mailed thread to kidnap his daughter at college. Hank hired a personal bodyguard, an Atlanta policeman named Calvin Wardlaw. He even stayed in a separate hotel from his teammates -- not because he wasn't allowed in the same hotel with his white teammates, as had been the case 20 years ago, but for his teammates' protection from anyone who might come after Hank.

On April 2, 1974, as the new season approached, NBC broadcast a baseball-themed special hosted by Bob Hope. The legendary entertainer had once been a part-owner of the Cleveland Indians. Among the special's sketches was a scene in which Aaron was on line at a supermarket. The woman behind the register said, "That'll be $7.14." Hank counted his money and said, "I have $7.13. Would you settle for that?" The cashier said, "Would you?" Hank looked at the camera and said, "no."

Mathews said he would hold Hank out of the season-opening series in Cincinnati against the Reds, so that he could tie and break the record at home. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, never missing an opportunity to be a cold-hearted jerk, told Braves management that the team would be fined if Hank wasn't played in at least 2 out of the 3 games, because the Braves were supposed to be fielding their best possible team. (But Commissioners, including Kuhn, have never had a problem with teams saving money with "fire sales.")

Kuhn made things worse by saying that he would not be attending the Braves' home opener, because he already had a speaking engagement in Cleveland that night. Finally, he bowed to public pressure, and announced he would attend the opener in Cincinnati. Gerald Ford, then the Vice President of the United States, would also be in attendance at Riverfront Stadium.

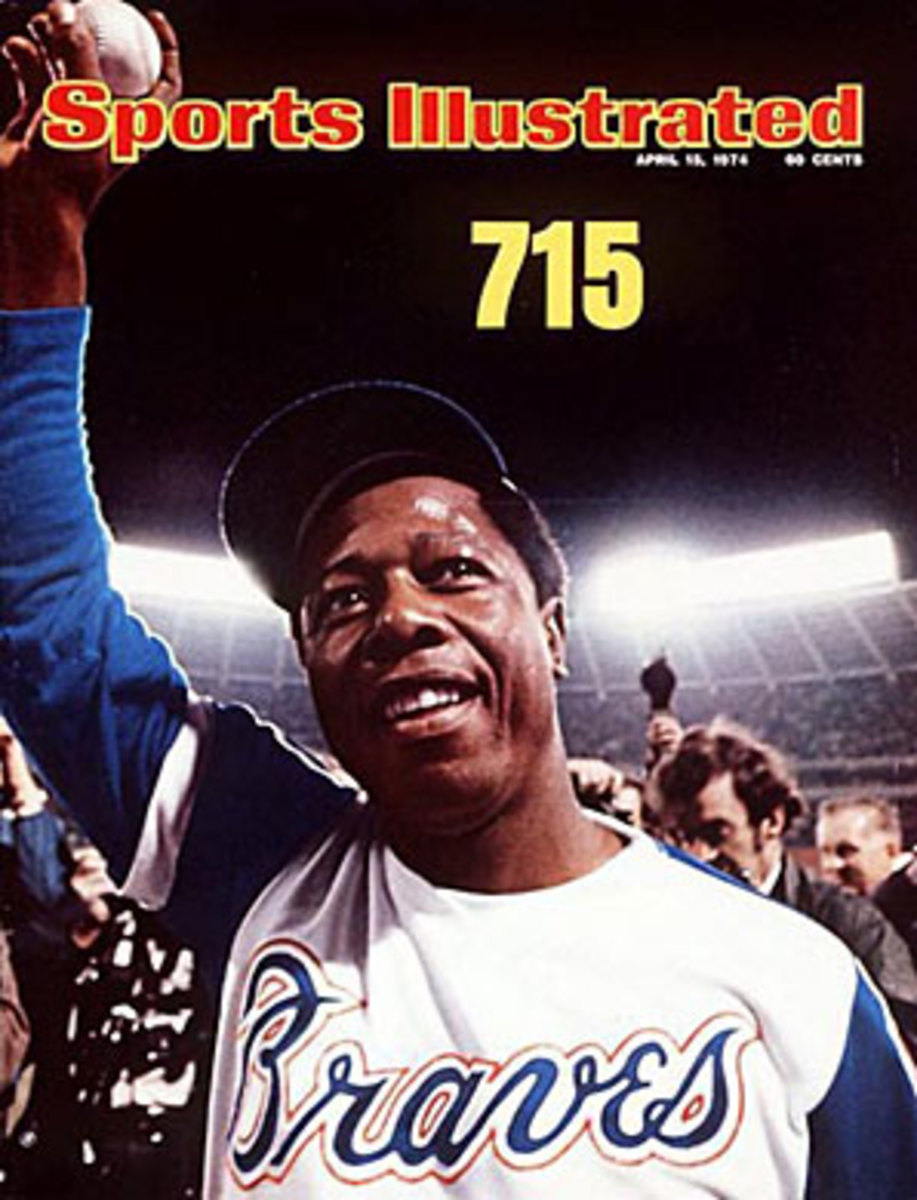

In the top of the 1st inning, with 1 out, Ralph Garr on 2nd and Mike Lum on 1st, Hank drilled a pitch from Jack Billingham over the fence in left-center field. It was Number 714. When he got to 3rd base, he got a handshake from Pete Rose, who would have a similar moment on that field in 1985, when he officially surpassed Ty Cobb for most career hits. When he got to home plate, he received a handshake from Johnny Bench.

The record had been tied. It was his only hit on the day, and the Reds won, 7-4. Mathews held him out of the next game, which the Reds won, 7-5. He went 0-for-3 in the next game, which the Braves won, 5-3.

April 8, 1974. Opening Night in Atlanta. The attendance was announced as 53,774, and it remains a home record for the Braves franchise, in any city. The game was broadcast live on NBC, just in case. The Braves were playing the Los Angeles Dodgers, who were wearing black armbands in memory of Bobbie McMullen, wife of Dodger 3rd baseman Ken McMullen. She had died of cancer 2 days earlier.

Kuhn was not in attendance. Nor was Ford. Nor was Nixon, who was getting deeper and deeper into Watergate. But the Governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, was there. So was the Mayor of Atlanta, the city's 1st black man so elected, Maynard Jackson. So was Pearl Bailey, who sang the National Anthem, as she had for the Mets' World Series clincher in 1969. So was Sammy Davis Jr. The great song-and-dance man said he would pay $25,000 -- about $131,000 in today's money -- for the record-breaking home run ball.

Al Downing was the starting pitcher for the Dodgers. The lefthander from Trenton, New Jersey had been the 1st black pitcher for the Yankees, in 1961. In 1964, he had led the American League in strikeouts, the 1st black pitcher to have done that. He had worn Number 24 for the Yankees, the same number that Mays had made famous with the Giants. Now, with the Dodgers, he was wearing 44, the same number as Aaron.

Hank led off the bottom of the 2nd, and drew a walk. Dusty Baker doubled him home, to give the Braves a 1-0 lead. The Dodgers took a 3-1 lead in the top of the 3rd, and still held it in the bottom of the 4th. Darrell Evans reached 1st base on an error. That brought Hank to the plate.

Downing threw a curveball, and it went into the dirt for ball 1. At 9:07 PM Eastern Daylight Time, he threw another fastball.

Milo Hamilton had the call for WGST, 920 on the AM dial (now WGKA):

Henry Aaron, in the second inning, walked and scored. He's sittin' on 714. Here's the pitch by Downing. Swinging. There's a drive into left-center field! That ball is gonna be... outta here! It's gone! It's 715! There's a new home run champion of all time, and it's Henry Aaron! The fireworks are going! Henry Aaron is coming around third! His teammates are at home plate! And listen to this crowd! This sellout crowd is cheering Henry Aaron, the home run king of all time!"

Because of Hamilton's call, Aaron would spend the rest of his life being called "the Home Run King," much more than "the home run leader."

The Dodgers' telecast, on KTTV-Channel 11, had Vin Scully with the call. Having broadcast for the team since 1950, when they were still in Brooklyn, and still had black MLB pioneers like Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe, he knew what the moment meant:

One ball and no strikes, Aaron waiting, the outfield deep to straightaway. Fastball, there's a high drive to deep left-center field! Buckner goes back, to the fence, it is gone!

Scully then paused, as Aaron got around the bases and reached home plate, then resumed:

What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the State of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world: A black man is getting a standing ovation, in the Deep South, for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.

It was a marvelous moment, and it was embraced by 99.99 percent of baseball fans. Writing about the event 30 years later, Tom Stanton would title his book about the record chase Hank Aaron and the Home Run That Changed America.

Bill Buckner was the Dodgers' left fielder that night. He climbed the fence to try to catch the ball, but he had no chance. After his error allowed the winning run to score in the Mets' Game 6 win over the Boston Red Sox in the 1986 World Series, someone suggested that, in concert with "The Curse of the Bambino" on the Red Sox, Ruth was punishing Buckner for not catching the ball. This was stupid: How did this person explain all the other outfielders who failed to catch Aaron's home run balls, and weren't "punished"? Or Downing, and the other pitchers who gave them up?

There was a scary moment. With all of the death threats, including from some men claiming they would be in attendance with rifles to shoot Hank before he could reach home plate (as if the home run wouldn't have counted anyway), bodyguard Wardlaw was looking around with binoculars for men with guns, like a Secret Service agent, and had his own gun ready.

After all, it had been 11 years since the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and civil rights leader Medgar Evers; 9 years since that of Malcolm X; 8 years since The Beatles had gotten death threats on their last tour; 6 years since the assassinations of Dr. King and Senator/Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, and the shooting of painter Andy Warhol; 4 years since an attempted assassination of Pope Paul VI; and 2 years since an attempted assassination of Governor George Wallace of Alabama during a Presidential campaign. People already knew that celebrities were not necessarily safe.

(The following year would see 2 failed attempts to assassinate Ford, by then the President. Five years after that, former Beatle John Lennon would be shot and killed. Within 4 months of that, President Ronald Reagan would be shot and nearly killed.)

Wardlaw knew that Hank was still in danger. And Britt Gaston (on the left in the photo) and Cliff Courtenay, 2 long-haired 17-year-olds from Waycross, Georgia, ran onto the field, and patted Hank on the back. It happened quickly, and Wardlaw had to make a quick decision as to what do to. In 2005, he recalled:

People asked me afterward, "Where were you for the big moment, Calvin?" And I tell them that my instinct was, at that moment, that, even if I could have gotten out there, my man was not in danger. And I tell them something else: What if I had decided to shoot my two-barreled .38 at those two boys, if I thought he was in a life-threatening situation, and had hit Hank Aaron instead, on the night he hit No. 715?

Gaston and Courtenay were arrested for disorderly conduct and trespassing, but nothing worse than that. Gaston's father bailed them out of jail at 3:30 AM, paying $100 for each of them. The next morning, the charges were dropped. Taking no chances, Estella Aaron wrapped her arms around her son right after he got to home plate, as if to say, "If you want to hurt my son, you'll have to go through me, first." Herbert Sr., Herbert Jr. and Tommie were also there.

Gaston went on to run a graphics business in South Carolina, was a season-ticket holder for University of Georgia football, and died of cancer in 2012, at age 55. Courtenay is now 63 years old, and an optometrist in Valdosta. Both had become friends with Aaron.

The ball dropped in front of an ad for BankAmericard, whose name was changed to Visa in 1976. It landed in the Braves' bullpen, where it was caught by reliever Tom House. House left the bullpen, and presented Hank with the ball. It was not sold to Sammy Davis Jr. It now resides in the museum section of the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, as does the bat Hank hit it with, and so does the entire uniform that he wore that day.

Governor Carter gave him a Georgia license plate with his initials and the magic number: HLA 715.

Jimmy, Hank and Billye

"Thank God it's over," he would say. Oh, yes, the game: The Braves scored twice more in that bottom of the 4th inning, and went on to win, 7-4.

Hank finished the season with 20 home runs at age 40, and 733 for his career. That remains a record for home runs for a single team. (Ruth hit 659 for the Yankees.)

*

In 1970, Bud Selig, a Milwaukee car dealer who had been trying to bring MLB back to his hometown after the Braves left, had bought the bankrupt Seattle Pilots, moved them to Milwaukee County Stadium, and given them the name of every pro baseball team in the city before the Braves: The Milwaukee Brewers. At the time, they were in the American League, which, unlike the National League, had adopted the designated hitter.

On November 2, 1974, recognizing that even he had slowed down -- he had been mainly a 1st baseman from 1971 onward, and was playing left field the night he hit Number 715 -- the Braves traded Hank Aaron back to his 1st major league city. He went to the Brewers, who sent the Braves outfielder Dave May, who had been an All-Star in 1973; and Roger Alexander, a pitcher then in Class AA, who ended up never making the major leagues.

Milwaukee fans welcomed Hank back with open arms. But it soon became clear that he was at the end of the line. In 1975, he batted .234 with just 10 home runs, giving him 745. He was still selected to the All-Star Game, held in Milwaukee. It was his 24th, tying a record held by Musial and Mays.

In 1976, he batted .229. On July 20, batting at County Stadium against Dick Drago of the California Angels, he hit his 755th career home run. Nobody knew it at the time, but, with more than 2 months left in the season, it would be his last.

On October 3, the Brewers closed the season at home against the Tigers. Hank was the DH, and batted in his customary 4th position, despite all evidence that he was done. He singled home Charlie Moore in the bottom of the 6th, and was replaced by pinch-runner Jim Gantner, to a standing ovation.

It was his 3,771st career hit, then 2nd all-time behind only Ty Cobb. In other words, he had over 3,000 hits that weren't home runs. He had 1,477 extra-base hits, still a record: 624 doubles and 98 triples, to go with his 755 home runs. It was his 2,297th run batted in, also still a record. It gave him 6,856 total bases, also still a record.

He also retired with these statistics: A .305 batting average, a .374 on-base percentage, a .555 slugging percentage, and a 155 OPS+. And he retired with another interesting distinction: He was the last former Negro League player who was still playing Major League Baseball.

In case you're wondering: As a World Champion, an MVP, and a former batting champion, he got a contract for 1958 worth $35,000; as a man with over 500 career home runs, he got a contract for 1969 worth $92,500; as a man with over 500 home runs and 3,000 hits, he got a contract for 1971 worth $125,000; and in each of the last 2 seasons of his career, as the all-time leader in home runs, extra-base hits, total bases and RBIs, he made $240,000. That had been intended as the highest salary in baseball, until Catfish Hunter was declared a free agent and got a bigger one from the Yankees.

The Braves retired Number 44 for him, elected him to their team Hall of Fame, and dedicated a statue of him outside their ballpark. In each case, the Brewers did the same, though that was mainly in recognition for what he did for the Braves in Milwaukee.

In 1982, he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. It was his 1st year of eligibility, and he got 97.8 percent of the vote, 406 out of 415. Begging the question: Who were the 9 men who chose to not vote for Hank Aaron for the Hall of Fame?

In 1999, The Sporting News named its 100 Greatest Baseball Players. Hank was ranked 5th, trailing Ruth, Mays, Cobb and Walter Johnson. The same year, baseball fans voted him onto the Major League Baseball All-Century Team, which was introduced before Game 2 of the World Series. As luck would have it, the Braves had won the Pennant, so the ceremony was held at their new home, Turner Field. Hank threw out the game's ceremonial first ball.

Also that year, in connection with the 25th Anniversary of his breaking the record, Selig, now Commissioner of Baseball, founded the Hank Aaron Award. Just as the Cy Young Award goes to the best pitcher in each League, the Aaron Award goes to the best hitter.

When the Yankees signed Reggie Jackson for the 1977 season, he couldn't wear the Number 9 he had worn in Oakland and Baltimore, because it was worn by Graig Nettles. He wanted to switch to Number 42, in memory of Jackie Robinson. But it was given to pitching coach Art Fowler. So, to honor the newly-retired Aaron, Reggie asked for Number 44.

Willie McCovey of the Giants also wore 44, because, like Aaron, he was a native of Mobile, Alabama. McCovey had also hit his 500th home run at Fulton County Stadium, in 1978. He finished his career with 521 home runs; Reggie, with 563.

On July 6, 2002, Reggie was given a Plaque for Monument Park at Yankee Stadium. His father, Martinez "Marty" Jackson, had played in the Negro Leagues. So, to the ceremony, he invited 3 men who, like himself, had hit over 500 home runs in the major leagues, and had, like his father, played in the Negro Leagues: Hank Aaron, Willie Mays and Ernie Banks.

When Turner Field opened for the 1997 season, its address was 755 Hank Aaron Drive. Fulton County Stadium was torn down, to make way for parking for Turner Field, but the sign beyond the left field fence to mark where the record-breaking ball fell was restored to its former spot, on a fence.

In 2017, Turner Field was replaced by SunTrust Park, now named Truist Park, whose address is 755 Battery Avenue. Because the City of Atlanta didn't want to give up the Aaron statue outside Turner Field, a new statue of Hank was dedicated at Truist Park's Monument Garden.

Hank was elected to the Sports Halls of Fame of the States of Alabama, Georgia and Wisconsin. The NAACP awarded him their Spingarn Medal for 1976. In 1997, his hometown of Mobile opened the 6,000-seat Hank Aaron Stadium. Honoring him, but also a family of local activists, the address is 755 Bolling Brothers Boulevard. In 2002, President George W. Bush, a former owner of the Texas Rangers, gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Clinton Yates of ESPN has suggested that, in order to get away from the Native American mascot controversy, the Braves should change their name to the Atlanta Hammers. Maybe in time for the 2024 season, the 50th Anniversary of the record-breaking home run?

After his retirement, Aaron was hired by the Braves' front office. Even more so than as an active player, he fought for more inclusiveness in baseball. The Braves became the 1st team to hire a black general manager, Ed Lucas. And he was among the people who convinced the Hall of Fame to take another look at black players before Jackie Robinson, even before the establishment of the first Negro League in 1920, to consider them for election.

There are now 10 men in the Hall who played in the Negro Leagues and the major leagues: Aaron, Mays, Banks, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Larry Doby, Satchel Paige, Monte Irvin, Willard Brown, and Leroy "Satchel" Paige -- a Mobile native, like Aaron.

There are 27 in the Hall who played only in the Negro Leagues: Andrew "Rube" Foster, his brother Bill Foster, Josh Gibson, Walter "Buck" Leonard, James "Cool Papa" Bell, William "Judy" Johnson, Oscar Charleston, Martín Dihigo, John Henry "Pop" Lloyd, Ray Dandridge, Leon Day, Willie Wells, Bullet Joe Rogan, Smokey Joe Williams, Norman "Turkey" Stearnes, Hilton Smith, Ray Brown, Andy Cooper, Pete Hill, Biz Mackey, José Méndez, Cum Posey, Louis Santop, Mule Suttles, Ben Taylor, Cristóbal Torriente and Jud Wilson.

There is also Frank Grant, who played before the institution of the Negro Leagues; and 4 Negro League executives: J.L. Wilkinson, Sol White, Alex Pompez, and the only woman in the Hall of Fame, Effa Manley.

On August 7, 2007, Barry Bonds of the San Francisco Giants stepped to the plate against Mike Bascik of the Washington Nationals, and hit his 756th career home run. Already having the single-season home run record, with 73 in 2001, he now held the career record as well. He would finish the season with 763, and retire.

I did not see Hank hit Number 715. Even though it was only 9:07 PM Eastern Time, my mother made me go to bed. And, at the age of 4, I wouldn't have been aware of it, anyway.

I did not see Barry hit Number 756. It was 11:46 PM Eastern Time, but, at that point in my life, staying up late wasn't an issue. Nor was access: The game was on ESPN. I chose not to watch it, because I knew that Bonds had cheated, using performance-enhancing drugs, probably from the 1999 season onward, in response to the fuss made over Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa both surpassing Roger Maris' single-season record in 1998, while he, a better all-around player than either, wasn't getting the same kind of attention.

Aaron was a better sport about it than I was. Although he didn't go to San Francisco for the game, he taped a message to be played on the video board at what's now named Oracle Park:

I would like to offer my congratulations to Barry Bonds on becoming baseball's career home run leader. It is a great accomplishment which required skill, longevity, and determination. Throughout the past century, the home run has held a special place in baseball, and I have been privileged to hold this record for 33 of those years.

I move over now and offer my best wishes to Barry and his family on this historical achievement. My hope today, as it was on that April evening in 1974, is that the achievement of this record will inspire others to chase their own dreams.

Bonds was now, and remains, and is likely to remain for a very long time, the all-time home run leader. But, for so many, Aaron was, and is, still the Home Run King. Including myself: Every time I look at a digital clock and see either 7:15 or 7:55, I think of Hank Aaron. Even though I wasn't old enough to have watched it, and have never lived anywhere near either Milwaukee or Atlanta.

*

On February 19, 2020, I waited to be admitted to a hospital, as I was scheduled for hip replacement surgery. The waiting room had NBC's The Today Show on the TV, and Hank was interviewed. Although age and infirmity had left him in a wheelchair, his mind was still sharp, and his hopes for a good future, for baseball and for America, were intact.

That gave me a good feeling as I went in. I am glad that, for 51 years, I shared a planet, and for 47 seasons, I shared a love of a sport, with Henry Louis Aaron.

Sadly, today, January 22, 2021, that share came to an end. Hank died of a stroke in his sleep, at his home in Atlanta. He was 86 years old.

His death leaves 8 surviving members of Milwaukee's only World Series-winning team, the 1957 Braves: Del Crandall, Félix Mantilla, Bobby Malkmus, Mel Roach, John DeMerit, Juan Pizarro, Taylor Phillips and Joey Jay.

It leaves 11 surviving members of the Major League Baseball All-Century Team: Willie Mays, Brooks Robinson, Sandy Koufax, Pete Rose, Nolan Ryan, Johnny Bench, Mike Schmidt, Cal Ripken, Roger Clemens, Mark McGwire, Ken Griffey Jr.

It leaves Mays and Rocky Colavito as the only surviving players from the 1960 TV series Home Run Derby.

And it leaves Mays as the only surviving player from the 1950s segment of Terry Cashman's song "Talkin' Baseball (Willie, Mikcey and the Duke)."

Here is some of the reaction:

* Brian Snitker, current manager of the Braves: "I don't know if tough even describes it. The Braves family lost another one of our biggest fans. I wouldn't be sitting here if it wasn't for Hank Aaron. He's the reason I'm here."

* Chipper Jones, a later Braves Hall-of-Famer: "He played for the Galactic All Stars... We're just mere Earthlings. He was on a different level."

* Frank Thomas, Chicago White Sox Hall-of-Famer, a 6-year-old kid in Georgia when Number 715 was hit: "I'm speechless! RIP to the greatest of all time Mr. Hank Aaron!! I'm just stunned. Hank was the standard of greatness for me."

* Reggie Jackson: "There are athletes that are regal, noble... that have this stature, the way they carry themselves, and we honor, we admire, we love them, they are very dear to us. And so, losing Hank Aaron was, for me, I was shocked."

* Magic Johnson, Basketball Hall-of-Famer with the Los Angeles Lakers, and owner of the defending World Champion Los Angeles Dodgers: "Rest in Peace to American hero, icon, and Hall of Famer Hank Aaron. I still remember where I was back in the day when he set the record, at that time, to become the home run all time leader. While a legendary athlete, Hank Aaron was also an extraordinary businessman, and paved the way for other athletes like me to successfully transition into business. Hank Aaron is on the Mount Rushmore for the greatest baseball players of all time! Rest In Peace my friend. Cookie and I are praying for the entire Aaron family."

* Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Magic's Hall of Fame teammate on the Lakers, previously played for the Bucks, making him Hank's fellow Milwaukee sports legend: "One of my heroes died today. RIP Hank Aaron."

* Bill Russell, Basketball Hall-of-Famer with the Boston Celtics: "Heartbroken to see another true friend & pioneer has passed away. @HenryLouisAaron was so much better than his reputation! His contributions were much more than just baseball."

* A spokesman for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City: "Our NLBM family joins the baseball world in mourning the lost of legendary Henry Aaron. Mr. Aaron was no stranger to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. More like family. This one hurts us for sure."

* Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States, and Governor of Georgia when Hank broke the record: "Rosalynn and I are saddened by the passing of our dear friend Henry Aaron. One of the greatest baseball players of all time, he has been a personal hero to us. A breaker of records and racial barriers, his remarkable legacy will continue to inspire countless athletes and admirers for generations to come. We send our love to Billye and their family and to Hank's many fans around the world."

* Keisha Lance Bottoms, Mayor of Atlanta: "While the world knew him as ‘Hammering Hank Aaron’ because of his incredible, record-setting baseball career, he was a cornerstone of our village, graciously and freely joining Mrs. Aaron in giving their presence and resources toward making our city a better place."

* Rev. Raphael Warnock, newly-sworn in as a U.S. Senator from Georgia: "As a proud Georgian & American, I celebrate the life and mourn the passing of Hank Aaron - a sports icon who broke records on the field, while also breaking barriers in the field of civil rights and human relations."

* Rev. Bernice King, daughter of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., both Atlanta natives: "We will miss you. Your leadership. Your grace. Your generosity. Your love. Thank you, #HankAaron."

* Kay Ivey, Governor of his home State of Alabama: "From his legendary career to his civil rights activism, he inspired many young boys and girls to pursue their dreams and pursue excellence in whatever they do."

* Lenny Kravitz, music legend: "Hank Aaron, my childhood baseball hero, has gone home. Watching him break Babe Ruth’s record for most home runs on television was a monumental moment. As a young black child, he inspired me to push for excellence. Rest easy Sir."

* Stephen King, horror novelist and noted Boston Red Sox fan: "RIP The Hammer -- Hank Aaron has passed away. Could he play the game, or what?"

* President Joe Biden: "Each time Henry Aaron rounded the bases, he wasn't just chasing a record, he was helping us chase a better version of ourselves -- melting away the ice of bigotry to show that we can be better as a nation. He was an American hero. God bless, Henry 'Hank' Aaron."

Aaron lived to see 15 different Presidents of the United States, from Franklin Roosevelt until Biden.

But if baseball had a King in this era, it was Hank Aaron. "The King is dead, long live the King."