The England team was loaded. From 1949 and 1950 Football League Champions Portsmouth: Midfielder Jimmy Dickinson. From 1950 FA Cup winners Arsenal: Defender Laurie Scott. From 1949 FA Cup winners Wolverhampton Wanderers, who would go on to win 3 League titles in the 1950s: Defender Billy Wright (the national team's Captain), forward Jimmy Mullen, and goalkeeper Bert Williams.

From 1948 League Champions Manchester United: Defender John Aston and midfielder Henry Cockburn. From 1947 League Champions Liverpool: Midfielder Laurie Hughes. From the Tottenham Hotspur team that would win the 1951 League title: Goalkeeper Ted Ditchburn, defender Alf Ramsey (who would manage England to the 1966 World Cup win), and midfielders Bill Nicholson (who would manage Tottenham to the 1961 League and Cup "Double") and Eddie Baily. From the Newcastle United team that would win 3 of the next 5 FA Cups: Forward Jackie Milburn.

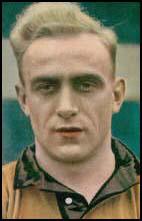

From the Blackpool team that would win the 1953 FA Cup, a pair of geniuses: Right wing Stanley Matthews (known as the Wizard of the Dribble) and forward Stan Mortensen. From Preston North End: Forward Tom Finney. From Middlesbrough: Forward Wilf Mannion.

It speaks to the talent of this team that 6 of the players -- Wright, Nicholson, Milburn, Matthews, Finney and Mannion -- would have statues dedicated outside their teams' stadiums.

The U.S. team was taken from various clubs in the top league in the country at the time, the American Soccer League. There was nothing like a "first division" as in European or South American countries. And none of them was still in college, although they weren't over the hill: One player was 38, the rest were between the ages of 21 and 31, coming from ASL clubs in New York, Philadelphia, the Boston satellite city of Fall River, Pittsburgh, Chicago and St. Louis.

England started by beating Chile 2-0. The U.S. got off to a good start against Spain, jumping ahead 1-0 in the 17th minute. But the defense allowed 3 goals between the 81st and 89th minutes, and Spain won, 3-1.

This set up the U.S.-England meeting, at Estádio Independência in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil on Thursday, June 29, 1950, 70 years ago today. Surely, this would be an easy England win, and nobody would talk about it forever.

As a British citizen familiar with the English game, as well as that of the country he had adopted, the U.S. manager, Bill Jeffrey, told the press, "We have no chance," and called his team "sheep ready to be slaughtered." One of the English national newspapers, the Daily Express, wrote, "It would be fair to give the U.S. three goals of a start."

England had 8 shots on goal in the 1st 32 minutes. U.S. goalkeeper Frank Borghi put on a heroic performance. Then, in the 37th minute, game an Ed McIlvenny throw-in, taken by Walter Bahr, whose shot toward foal was deflected by the head of Joe Gaetjens, and the U.S. led 1-0.

In the last few minutes of the game, the England players appealed for a penalty and insisted that a deflected shot had gone over the goal line, but were denied by the referee each time. Final score: America 1, England 0.

On July 2, the Americans were knocked out of the tournament, losing 5-2 to Chile, and England fell to Spain 1-0. Spain thus won Group 2, and only the 4 Group winners advanced to a knockout round. Uruguay ended up beating Brazil in the Final, an even worse defeat for Brazil, but not nearly as shocking around the world as the U.S. beating England. (Uruguay had, after all, dominated international soccer in the 1920s, won the 1st World Cup in 1930, and, obviously, was still pretty good.)

The 1-0 win over England has been nicknamed "The Miracle Match." In a nod to the U.S. hockey upset over the Soviet Union at the 1980 Winter Olympics, known as "The Miracle On Ice," this game has been retroactively called "The Miracle On Grass." Given how many shots Borghi had to stop, Belo Horizonte '50 was much closer to being a miracle than Lake Placid '80.

5. The Weather. Brazil is a tropical nation. The Americans, especially the players from St. Louis, were used to the kind of heat they were facing. In contrast, the entirety of the British Isles is further north than the entirety of the continental United States.

The English (and the Welsh, and the Scots, and the Irish) may complain about the cold and the rain, and long to spend time on the warm coasts of France, Spain and Italy. But they don't actually like to play football in the heat. And they did not handle it as well as the Americans.

The old saw from American-style football, "Don't blame the weather, it was the same for both teams" is frequently untrue, especially when one team is used to cold weather and the other plays in a dome. If this game had been played anywhere in England, the English would probably have won it.

4. The Media Disparity. The English were under intense pressure, after not playing in the World Cups of the 1930s, to finally put their money where their mouths were, and prove they were the best team in the world.

Since the establishment of the European Championships in 1960, and especially after they finally did win the World Cup in 1966, every 2 years, the media builds up the national side, makes them seem unbeatable, and then roasts them when they inevitably fail.

But the Americans faced no media pressure. Because they faced no media. There was a grand total of one American reporter at the game, and he had to pay his own way, because his newspaper wouldn't pay it -- even though it was the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and there were a few St. Louisians on the roster. They wouldn't even "go for the local angle."

There were no annoying or embarrassing media questions for the U.S. team to dodge. There were no media questions at all.

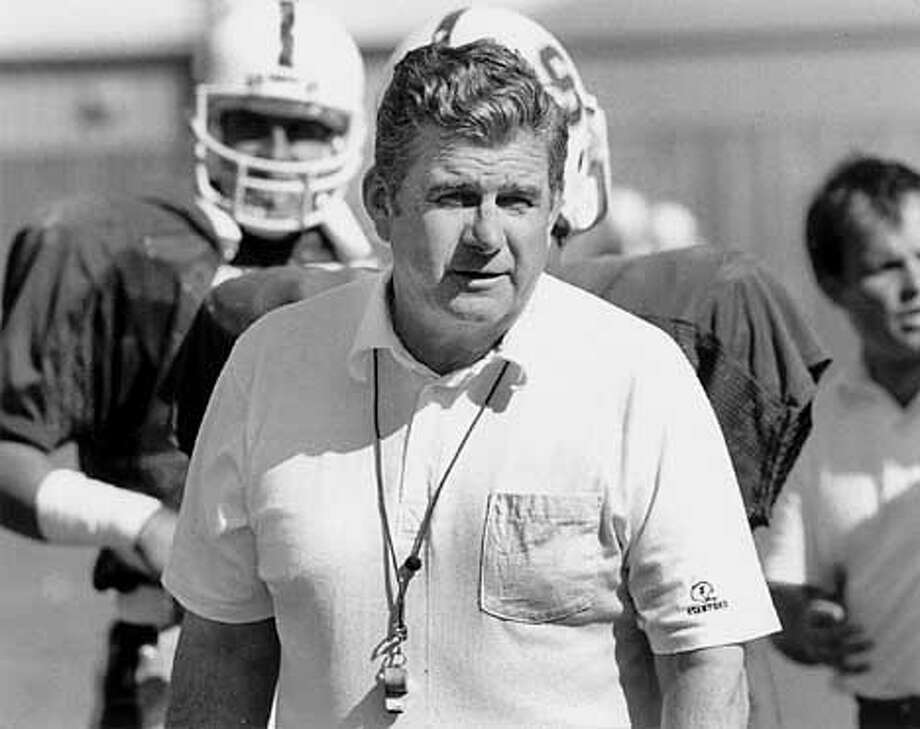

3. Walter Winterbottom. At the time, he was a 37-year-old native of Oldham, outside Manchester, who played a few games for Manchester United, but saw his career cut short by having to serve in World War II. In a rotten case of "It's not what you know, it's who you know," he became an officer in the Royal Air Force, and gained access to Stanley Rous, the secretary of the governing body of English soccer, the Football Association (the FA).

In 1946, Rous talked the FA Council into appointing Winterbottom as the FA's 1st Director of Coaching, thus making him the national team's 1st real manager. He proved to be a bust. Under his leadership:

* 1949: England lost to the Republic of Ireland at Goodison Park in Liverpool, home of Everton. But that was considered a fluke. Or, as they would say in England, a one-off. As it turned out, it wasn't, not by a long shot:

* 1950: England lost to the United States in the World Cup in Brazil, and didn't make it out of the Group Stage.

* 1953: England lost on English soil to a team from outside the British Isles for the 1st time, getting embarrassed 6-3 by the "Magnificent Magyars" of Hungary at the original Wembley Stadium in London.

* 1954: England played a warmup match in Budapest, figuring another game with Hungary would be good preparation for the upcoming World Cup in Switzerland, but they got shellacked again, 7-1. lost. Maybe it was a good exercise after all: At the World Cup, they won their Group Stage. But they lost to defending Champions Uruguay in the Quarterfinal.

* 1958: England couldn't get out of the Group Stage of the World Cup in Sweden. To make matters more embarrassing, both Wales and Northern Ireland did make the knockout stage.

* 1962: England again reached the Quarterfinal of the World Cup, this time in Chile, but lost. At least it was to Brazil, the defending Champions, who won it again.

After that World Cup, Winterbottom was finally let go. If the current English media climate was in place in 1950, he probably would have been sacked before he got back on the plane. Especially since he left the already-beloved Stanley Matthews on the bench.

Can you imagine the reaction today if current England manager Gareth Southgate left his best player on the bench for a World Cup match? Then again, it's hard to say who that is. Raheem Sterling? Harry Kane, the diver and the great dribbler (and that doesn't refer to his footballing ability)? Jordan Henderson, who would be practically ignored by the media were he not Captain of Liverpool?

Regardless, in 2018, those guys started in 5 of the 6 games England played. Southgate only held them back from the last Group Stage game, because England had already advanced, and there was no reason to risk them for injury.

Stanley Matthews had been injured a few weeks before the 1950 World Cup, but was working his way back. Had he played, it's hard to imagine American goalie Frank Borghi keeping the same clean sheet against the kind of attacks Sir Stan would have launched.

Soccer historian David Goldblatt has suggested that Winterbottom failed to properly learn from his defeats: "His inability to anticipate or learn significantly from the Hungarian debacle suggests that his grasp of tactics and communication with the players was limited." Another writer, William Baker, said that, due to having upper-class origins, he could not "effectively instruct, much less inspire, working-class footballers." And longtime football journalist Brian Glanville said, "I got on very well with Walter Winterbottom, but he was a rotten manager." Nevertheless, he was knighted in 1978, and lived until 2002.

He was replaced by Alf Ramsey, who had played for him in the 1950 disaster, helped Tottenham Hotspur win the League title in 1951, and had just managed Ipswich Town to the League title. He knew England would host the World Cup in 1966, and he told the FA he could manage them to victory. He was right.

2. No Scouting. In the modern era, a national team would collect as much footage of an upcoming opponent as possible, and study the hell out of it, looking for any possible weakness. But there was no film of the U.S. team for the English to study. It wouldn't matter if they'd decided to look at it before leaving for Brazil, because there was no "it" to look at.

And the reports they had read about the U.S. team? They couldn't possibly have been reliable. They had no way of knowing whether Brookhattan, Ponta Delgada, or St. Louis Simpkins-Ford, and the players they were sending to Brazil on the U.S. team, were any good, or what their tendencies were.

And therein lay the biggest problem of all:

1. The Americans Were Good. In an exercise like this, the tendency is to make Reason Number 1 "The opposition were better." There's no way the U.S. team was better than the England team. But, as with the Pittsburgh Pirates against the Yankees in the World Series 10 years later, they were a good team, worthy of being on the field with the alleged world's best, and the fact that they won should not be considered that much of a shock.

You could say that, in their 1st game in the tournament, the U.S. defense collapsed at the end and let Spain win 3-1. Or you could say that they were 10 minutes from having a famous 1-0 win 4 days sooner than the one they actually got.

Yes, they got pounded 5-2 by Chile in their finale. But had they held that 1-0 lead against Spain, they would have finished atop the Group, and advanced to the Final Group. Would the win over England still have been considered an upset? Of course. Would it have been as much of a shock? No.

Put it all together, and accept that the conditions for England to win that game weren't so good, and you really can't blame them for losing. Their manager, yes. The players, no.

VERDICT: Not Guilty.

The 1-0 win over England has been nicknamed "The Miracle Match." In a nod to the U.S. hockey upset over the Soviet Union at the 1980 Winter Olympics, known as "The Miracle On Ice," this game has been retroactively called "The Miracle On Grass." Given how many shots Borghi had to stop, Belo Horizonte '50 was much closer to being a miracle than Lake Placid '80.

The Miracle On Grass was hardly seen then, and it has hardly been seen since. But it might just be the greatest upset in American sports history.

How could England have lost this game?

Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame England for Losing to the U.S. at the 1950 World Cup

How could England have lost this game?

Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame England for Losing to the U.S. at the 1950 World Cup

5. The Weather. Brazil is a tropical nation. The Americans, especially the players from St. Louis, were used to the kind of heat they were facing. In contrast, the entirety of the British Isles is further north than the entirety of the continental United States.

The English (and the Welsh, and the Scots, and the Irish) may complain about the cold and the rain, and long to spend time on the warm coasts of France, Spain and Italy. But they don't actually like to play football in the heat. And they did not handle it as well as the Americans.

The old saw from American-style football, "Don't blame the weather, it was the same for both teams" is frequently untrue, especially when one team is used to cold weather and the other plays in a dome. If this game had been played anywhere in England, the English would probably have won it.

4. The Media Disparity. The English were under intense pressure, after not playing in the World Cups of the 1930s, to finally put their money where their mouths were, and prove they were the best team in the world.

Since the establishment of the European Championships in 1960, and especially after they finally did win the World Cup in 1966, every 2 years, the media builds up the national side, makes them seem unbeatable, and then roasts them when they inevitably fail.

But the Americans faced no media pressure. Because they faced no media. There was a grand total of one American reporter at the game, and he had to pay his own way, because his newspaper wouldn't pay it -- even though it was the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and there were a few St. Louisians on the roster. They wouldn't even "go for the local angle."

There were no annoying or embarrassing media questions for the U.S. team to dodge. There were no media questions at all.

3. Walter Winterbottom. At the time, he was a 37-year-old native of Oldham, outside Manchester, who played a few games for Manchester United, but saw his career cut short by having to serve in World War II. In a rotten case of "It's not what you know, it's who you know," he became an officer in the Royal Air Force, and gained access to Stanley Rous, the secretary of the governing body of English soccer, the Football Association (the FA).

In 1946, Rous talked the FA Council into appointing Winterbottom as the FA's 1st Director of Coaching, thus making him the national team's 1st real manager. He proved to be a bust. Under his leadership:

* 1949: England lost to the Republic of Ireland at Goodison Park in Liverpool, home of Everton. But that was considered a fluke. Or, as they would say in England, a one-off. As it turned out, it wasn't, not by a long shot:

* 1950: England lost to the United States in the World Cup in Brazil, and didn't make it out of the Group Stage.

* 1953: England lost on English soil to a team from outside the British Isles for the 1st time, getting embarrassed 6-3 by the "Magnificent Magyars" of Hungary at the original Wembley Stadium in London.

* 1954: England played a warmup match in Budapest, figuring another game with Hungary would be good preparation for the upcoming World Cup in Switzerland, but they got shellacked again, 7-1. lost. Maybe it was a good exercise after all: At the World Cup, they won their Group Stage. But they lost to defending Champions Uruguay in the Quarterfinal.

* 1958: England couldn't get out of the Group Stage of the World Cup in Sweden. To make matters more embarrassing, both Wales and Northern Ireland did make the knockout stage.

* 1962: England again reached the Quarterfinal of the World Cup, this time in Chile, but lost. At least it was to Brazil, the defending Champions, who won it again.

After that World Cup, Winterbottom was finally let go. If the current English media climate was in place in 1950, he probably would have been sacked before he got back on the plane. Especially since he left the already-beloved Stanley Matthews on the bench.

Can you imagine the reaction today if current England manager Gareth Southgate left his best player on the bench for a World Cup match? Then again, it's hard to say who that is. Raheem Sterling? Harry Kane, the diver and the great dribbler (and that doesn't refer to his footballing ability)? Jordan Henderson, who would be practically ignored by the media were he not Captain of Liverpool?

Regardless, in 2018, those guys started in 5 of the 6 games England played. Southgate only held them back from the last Group Stage game, because England had already advanced, and there was no reason to risk them for injury.

Stanley Matthews had been injured a few weeks before the 1950 World Cup, but was working his way back. Had he played, it's hard to imagine American goalie Frank Borghi keeping the same clean sheet against the kind of attacks Sir Stan would have launched.

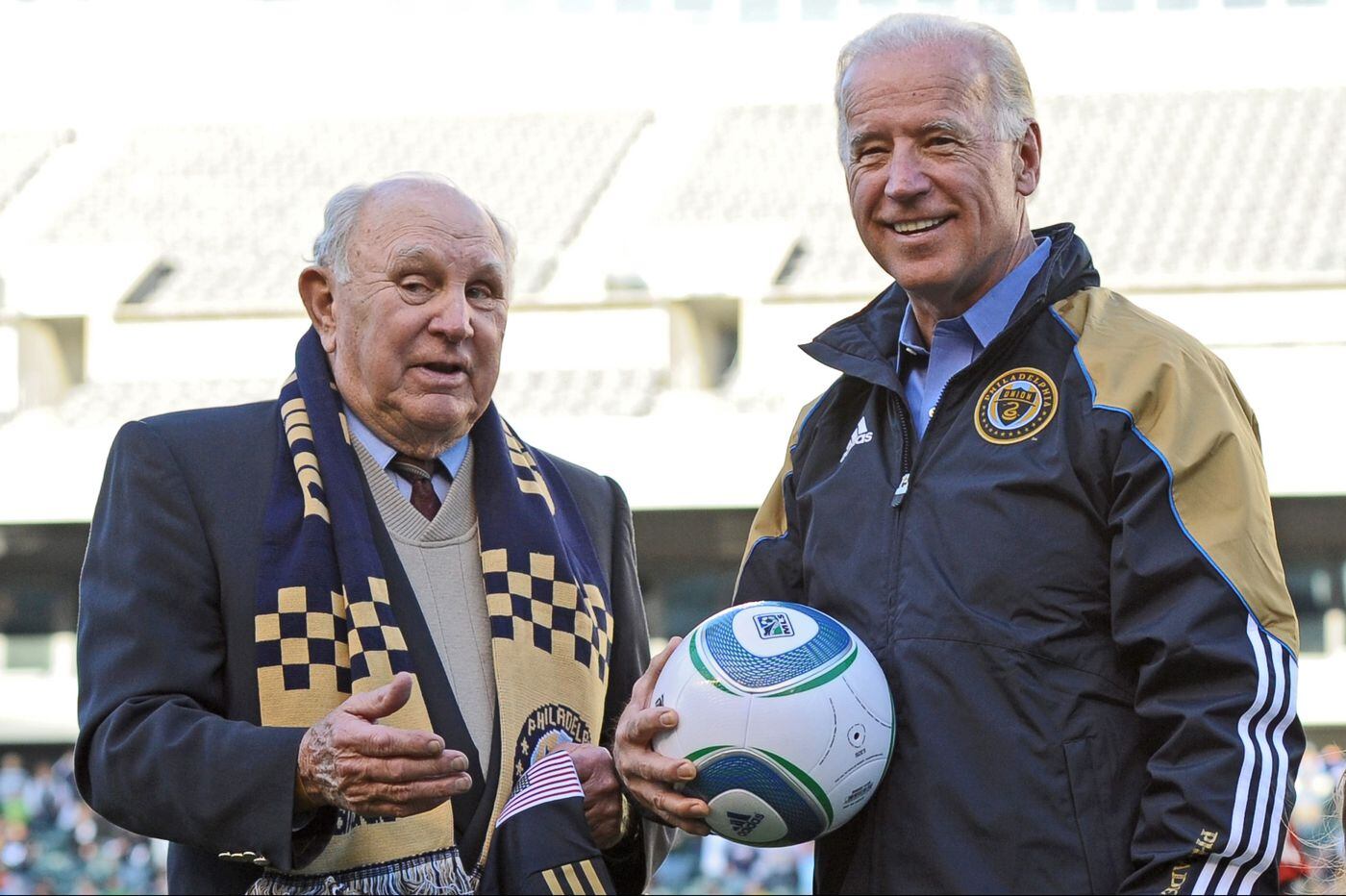

Sir Stan

Soccer historian David Goldblatt has suggested that Winterbottom failed to properly learn from his defeats: "His inability to anticipate or learn significantly from the Hungarian debacle suggests that his grasp of tactics and communication with the players was limited." Another writer, William Baker, said that, due to having upper-class origins, he could not "effectively instruct, much less inspire, working-class footballers." And longtime football journalist Brian Glanville said, "I got on very well with Walter Winterbottom, but he was a rotten manager." Nevertheless, he was knighted in 1978, and lived until 2002.

Good man? Maybe. Good intentions? Certainly.

Good manager? Yer havin' a laugh, mate.

He was replaced by Alf Ramsey, who had played for him in the 1950 disaster, helped Tottenham Hotspur win the League title in 1951, and had just managed Ipswich Town to the League title. He knew England would host the World Cup in 1966, and he told the FA he could manage them to victory. He was right.

2. No Scouting. In the modern era, a national team would collect as much footage of an upcoming opponent as possible, and study the hell out of it, looking for any possible weakness. But there was no film of the U.S. team for the English to study. It wouldn't matter if they'd decided to look at it before leaving for Brazil, because there was no "it" to look at.

And the reports they had read about the U.S. team? They couldn't possibly have been reliable. They had no way of knowing whether Brookhattan, Ponta Delgada, or St. Louis Simpkins-Ford, and the players they were sending to Brazil on the U.S. team, were any good, or what their tendencies were.

And therein lay the biggest problem of all:

1. The Americans Were Good. In an exercise like this, the tendency is to make Reason Number 1 "The opposition were better." There's no way the U.S. team was better than the England team. But, as with the Pittsburgh Pirates against the Yankees in the World Series 10 years later, they were a good team, worthy of being on the field with the alleged world's best, and the fact that they won should not be considered that much of a shock.

You could say that, in their 1st game in the tournament, the U.S. defense collapsed at the end and let Spain win 3-1. Or you could say that they were 10 minutes from having a famous 1-0 win 4 days sooner than the one they actually got.

Yes, they got pounded 5-2 by Chile in their finale. But had they held that 1-0 lead against Spain, they would have finished atop the Group, and advanced to the Final Group. Would the win over England still have been considered an upset? Of course. Would it have been as much of a shock? No.

Put it all together, and accept that the conditions for England to win that game weren't so good, and you really can't blame them for losing. Their manager, yes. The players, no.

VERDICT: Not Guilty.

.jpg)