Nice skyline, huh?

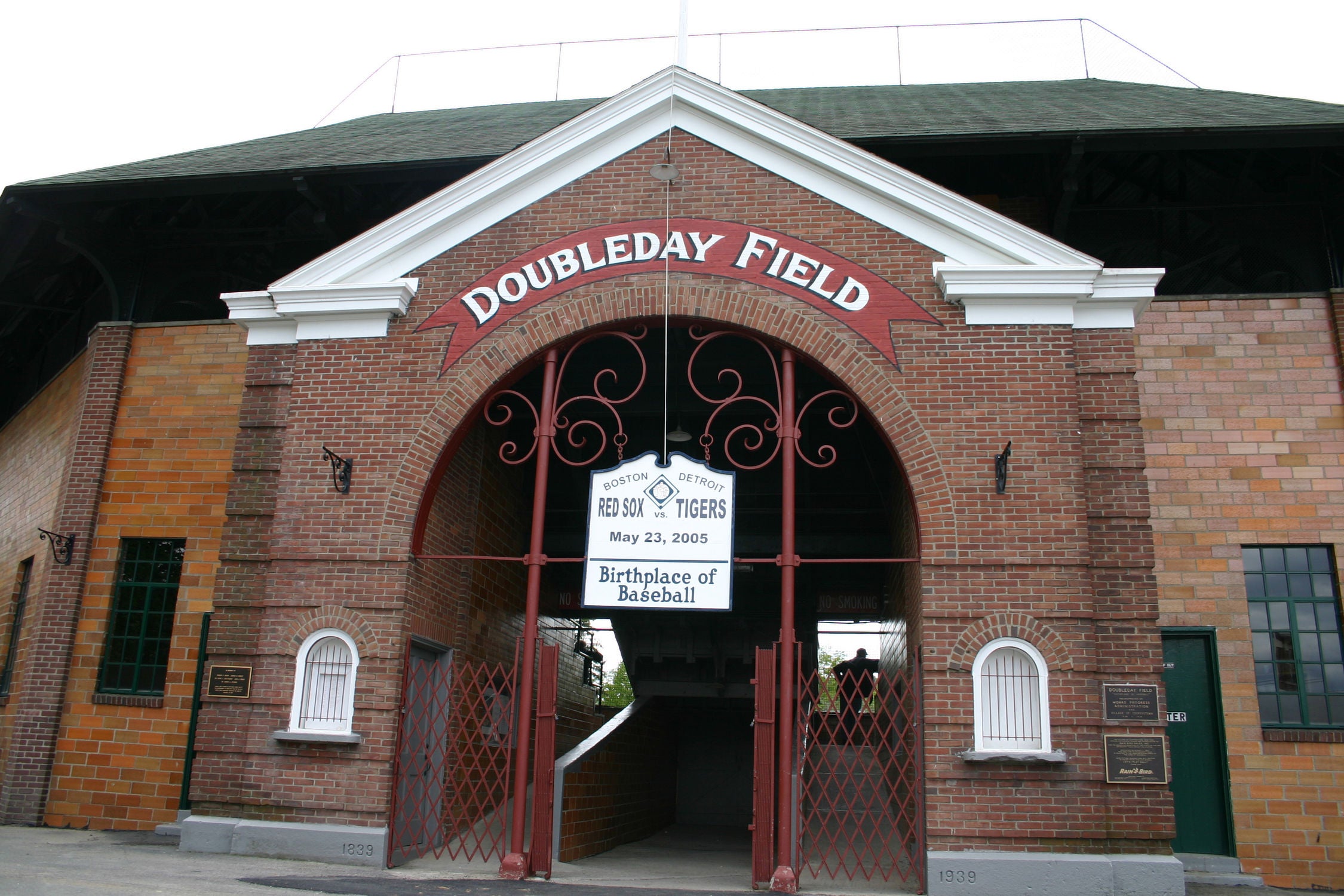

In 1939, the Baseball Hall of Fame opened in Cooperstown, New York. So did Doubleday Field, a small ballpark, supposedly on the site of baseball's invention. As part of the Hall's opening ceremonies, it hosted an old-timers' game, with players chosen by 2 members of the new Hall of Fame, Honus Wagner and Eddie Collins.

From 1940 to 2007, Doubleday Field hosted the annual Hall of Fame Game, between an American League team and a National League team. The 2008 game was meant to be the last one, but was canceled by rain, and there was no game in 2009. But in 2010, the Hall of Fame Classic began, returning to the old-timers' theme. Doubleday Field will host it this coming Saturday, May 27.

Before You Go. The temptation to go to Cooperstown may be highest when a player from your favorite team has been elected. Let me warn you: Unless this is your favorite player of all time, and you feel you must so honor him, do not go for Induction Weekend.

Cooperstown has never had more than 3,000 permanent residents, and it simply wasn't designed to host 100,000 visitors, but on Induction Weekend, it does. It's not the worst overflow that rural New York State has ever had: At least it smells better than Woodstock did.

Perhaps, without the added attraction of the actual induction ceremony, Hall of Fame Classic weekend will be more manageable. But the best time to go is probably in the Autumn, when the leaves are changing, and Central New York breaks out into spectacular color. That the World Series would be happening at the time is a nice bonus.

Cooperstown is a bit further north than New York City, so whatever the weather is in the City at the time, expect it to be a little cooler (or outright colder) in Cooperstown.

Tickets. Tickets for the Hall of Fame Classic are $12.50 for 1st base seats and 3rd base seats, and $11.00 for general admission seats in the outfield. They are available via phone at 1-877-726-9028, or at the Hall of Fame website.

As for the Hall itself, admission is $23 for adults, $15 for senior citizens (65 and up), $12 for veterans and children (7 to 12), and free to active or career retired military (with ID) and children (6 and under).

The Hall opens at 9:00 AM every day of the year except Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day and New Year's Day. From Memorial Day to Labor Day -- this year, May 28 to September 3 -- it is open until 9:00 PM. The rest of the year, it's open until 5:00 PM.

Getting There. It's 196 miles from Times Square to the Baseball Hall of Fame. It's also 189 miles from Yankee Stadium, 198 miles from Citi Field, 73 miles from the State Capitol in Albany, 94 miles from the Carrier Dome in Syracuse, 237 miles from Niagara Square in Buffalo, 238 miles from Fenway Park in Boston, 264 miles from downtown Montreal, and 219 miles from my home base in Central Jersey.

Even if it weren't that close, flying would be out of the question, as the nearest airport with regular passenger service -- unless you can afford a private plane -- is in Albany. There hasn't been passenger rail service to Cooperstown in decades. Getting there by bus is problematic: Adirondack Trailways runs service on Friday and Sunday only, 1 bus each day. Unless you want to go up Friday, stay over Friday and Saturday nights, and go back Sunday, you'd end up going up Friday or Sunday, and staying less than 3 hours -- and the Hall building itself should really be done over at least that much.

Really, the only way to get there is by driving. Take Interstate 87 North, as it becomes the New York State Thruway, and get off at Exit 25A. There may be a temptation to take your rest stop in Albany, the State Capital. It's a weird town, particularly in its architecture. The State Capitol, one of the few not to have a dome, looks like a medieval castle, but was completed in 1899. But it's surrounded by State office buildings that were either Art Deco masterpieces approved by Governor Alfred E. Smith in the 1920s, or Brutalist monstrosities approved by Governor Nelson Rockefeller in the 1960s.

The State Capitol in Albany

But considering the tangle of roads around Albany, I would advise you to take your biggest rest stop earlier, on the Thruway, and then getting back on, and continuing to Exit 25A. Take Interstate 88 West to Exit 24, then get on U.S. Route 20 West.

Now, you're 50 miles away. This doesn't sound like much, but this part is not going to be fun. The longest, most boring part of your trip is over, but here comes the most annoying part: It's a lot of going up a hill, with a nice view of the Catskill Mountains at the top, then coming back down the hill to a small town and one traffic light, then repeat.

At Cherry Valley, there will be a very nasty leftward curve. Take this curve very slowly, or it could turn out to be a "Dead Man's Curve." Make sure that it's still daylight when you get there, and if there's a chance that the weather could be bad, ask your GPS to find an alternate route before you leave your driveway. It won't be nearly as bad on the way back, as the rightward curve will be away from the big drop. But, on the way in, once you get past it, you're only 16 miles away.

At Springfield Center, make a left onto N.Y. Route 80 South. Now, you're only 11 miles away. You will soon have Lake Otsego on your left. You will then pass the Fenimore House on the left, and the Farmers' Museum on the right. Just 1 mile to go. Turn right on Chestnut Street, then, after 1 block, left on Main Street -- at the only traffic light in the Village. The Hall of Fame is 3 blocks ahead on your right.

If you do it right, you should spend 2 1/2 hours on the Thruway, and an hour the rest of the way. Counting a rest stop, it will be about 4 to 4 1/2 hours -- about the same as driving to Boston or Washington.

Once In the Village. Yes, it's "The Village of Cooperstown," not "The City" or "The Town" or "The Township" or anything like that. It was founded in 1786 by William Cooper, a merchant, a land speculator, a County Judge, and, in the 1795-97 and 1799-1801 terms, a Congressman from the Federalist Party.

Today, however, he is best known as the father of novelist James Fenimore Cooper, author of the 5 novels that are collectively known as The Leatherstocking Tales. For this reason, the teams at Cooperstown High School are known as the Redskins, and were so named before the NFL team of that name arrived in Washington, D.C. A statue of James is in the middle of Fair Street, a block south of Main.

Cooperstown has never had more than 3,000 permanent residents, and the 2010 Census listed its population at 1,852. It is the seat of Otsego County: Otsego is named for a Native American word meaning "place of the rock." The County is listed as having 62,259 people -- not even enough to fill the pre-renovation original Yankee Stadium.

ZIP Codes for Central New York start with the digits 13, including Cooperstown, at 13326. For the Hudson Valley, from Poughkeepsie on up to the border, they start with 12. For Western New York, including Buffalo and Rochester, they start with 14. The Sales tax in New York State, outside New York City, is 4 percent.

The Otsego County Courthouse,

about half a mile west of the Hall of Fame

Cooperstown doesn't really have a "centerpoint." Street addresses increase southward from the southern end of Lake Otsego, and westward from the river forming from it, the Susquehanna, which eventually flows through Pennsylvania, including its State capital of Harrisburg, and into Maryland's Chesapeake Bay. The area also doesn't have a beltway.

The newspaper for Otsego County is The Cooperstown Crier, named for "town criers" that would shout the news in olden days, before newspapers became widespread.

James Fenimore Cooper named Lake Otsego "Glimmerglass," and it can be very pretty. The Glimmerglass Festival operates every Summer, out of the 914-seat Alice Busch Opera Theater, on the lake, 8 miles north of downtown.

Parking is free on Main Street and other Village streets, but is limited to 2 hours, and, according to the Hall's website, this is "STRICTLY ENFORCED." The ALL CAPS are theirs, not mine.

The Cooperstown Trolley is a bus, designed to look like an old-time trolley, that runs to all local tourist attractions, including the Hall of Fame. From Memorial Day weekend (May 24) through Labor Day (September 1), it runs every day from 8:30 AM until its last departure from the Hall of Fame at 9:00 PM. From Labor Day through Columbus Day, it runs on weekends only, from 9:30 AM to 7:15 PM. An All Day Pass will let you ride it as many times as you want during a single day for $2.00. You can buy one from the driver.

A Trolley outside the Hall of Fame

Cooperstown is lovely. But it's hard to get to. In preparation for my 1st visit, in September 1985, I read a newspaper article that quoted someone as saying, "Nobody stumbles upon Cooperstown by accident. You have to want to come here."

So, Why Cooperstown? Why was this out-of-the-way little town (even if it is a County Seat) selected as the home of the Baseball Hall of Fame? Because it was selected as the "Birthplace of Baseball." Why was it selected as that? Long story.

In 1905, the National Commission, then the governing body for baseball, decided to settle the game's origins for once and for all, and appointed the Mills Commission, led by Abraham G. Mills, a former team executive, National League President, essentially the founder of the minor league system that prevailed until Branch Rickey rearranged things with his creation of the farm system, and the leader of the famous 1889 world tour of baseball players, which ended with a big banquet in New York that declared baseball a wholly American invention, in spite of the insistence of early baseball men, like the English-born sportswriter Henry Chadwick, that the game evolved from the English games of cricket and rounders.

The Commission included another former NL President, the 1st, noted Connecticut politician Morgan Bulkeley; and 2 early legends among players: George Wright, the shortstop of the 1st openly professional team, the 1869-70 Cincinnati Red Stockings, and star with the Boston team that would become the Braves; and Al Reach, a right fielder who starred in Philadelphia before founding the Phillies. Wright (rightly) and Bulkeley (less so) are in the Hall of Fame, while Mills (fairly) and Reach (unfairly) are not. But with guys like that on the Commission, essentially, the fix was in for finding an American origin for baseball.

Despite this, for nearly 3 years, the Mills Commission got nowhere. Finally, in late 1907, they found the story they needed, and they released it: Baseball was invented on June 12, 1839 in Cooperstown, New York, laid out in a cow pasture owned by the Phinney family, related to the Coopers by marriage, by Abner Doubleday.

This claim was given to the Commission by a 71-year-old mining engineer from Denver named Abner Graves (yes, also named Abner), who said that he witnessed Doubleday playing the then-popular game of "town ball," being played by students of 2 local schools on what came to be known as "Farmer Phinney's Lot," and watched Doubleday make the changes necessary to create a better version, and watched him give it the name "base ball."

Graves backed his story up by sending the Commission a diagram that, he said, Doubleday gave him. In 1934, someone visiting the Graves family in Cooperstown found a tattered ball, which was put on display in the Village Hall and later in the Hall of Fame itself (where it is still on display), and called "The Doubleday Ball," alleged to be the ball in the first game. The First Baseball.

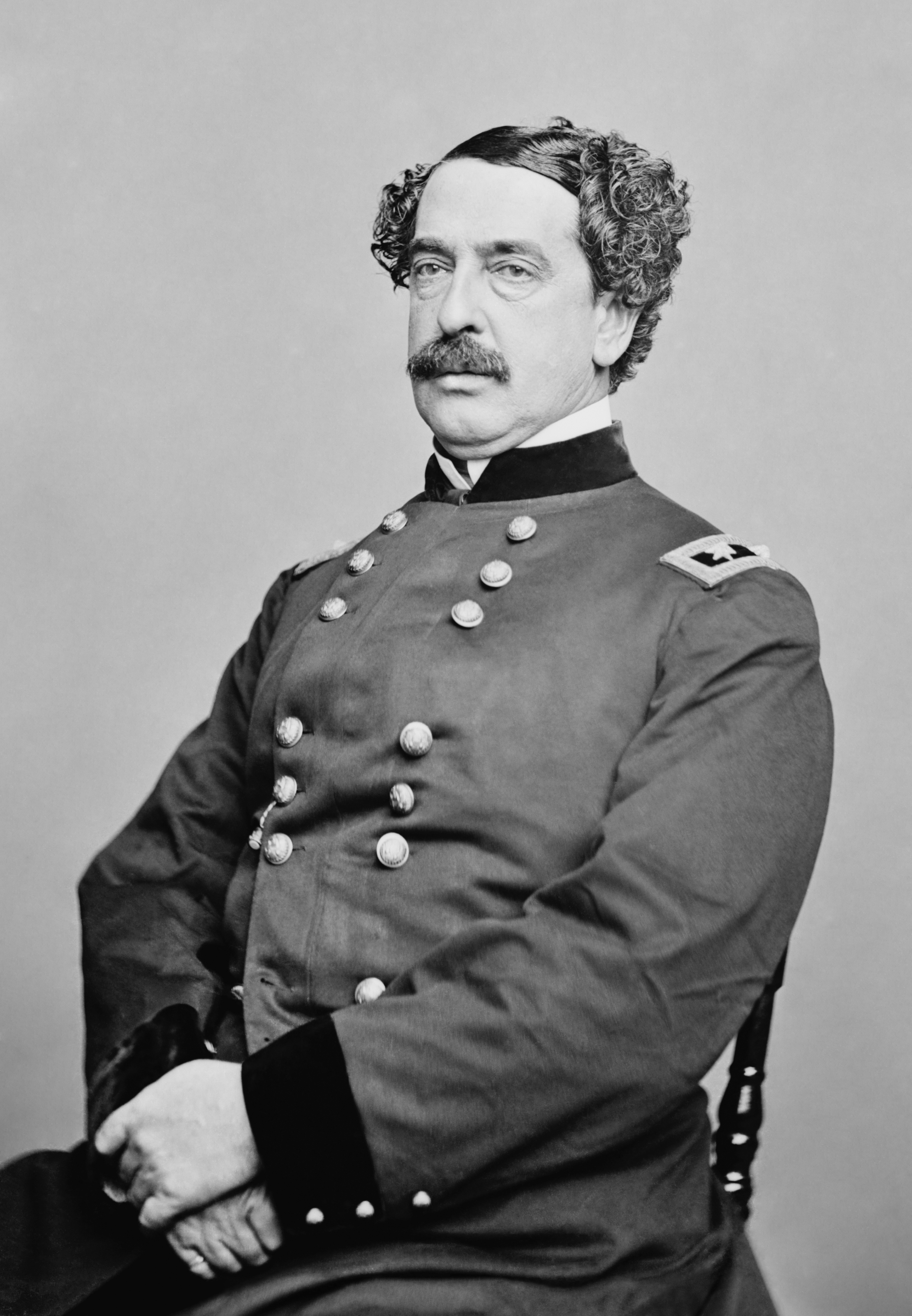

Abner Doubleday was a real person. And if you were going to make something up, he was a great choice. He was a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York -- 146 miles southeast of Cooperstown. He served in the Mexican-American War. He was second-in-command at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, when it was attacked on April 12, 1861, and he ordered the 1st Union shot in retaliation. Thus, he was there for the beginning of an epic story that would later chronicled by documentarian Ken Burns... The Civil War.

Abner Doubleday, an American hero,

and baseball was not among the reasons why.

He was one of the heroes of the Battle of Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. He rose to the rank of Major General -- 2 stars. His multi-volume journal has been a godsend for people studying American military life in the mid-19th Century, including the Civil War and the Indian Wars. He commanded an all-black regiment, with no incidents. He was a financial backer of Thomas Edison's inventions. He even founded San Francisco's famous cable car company.

On multiple levels, Abner Doubleday was a genuine American hero. And he was a New Jerseyan the last few years of his life, living in Mendham, Morris County -- also the hometown of Governor Chris Christie and Game of Thrones actor Peter Dinklage -- although he is rightly buried at Arlington National Cemetery, not far from an actual sports legend, Joe Louis.

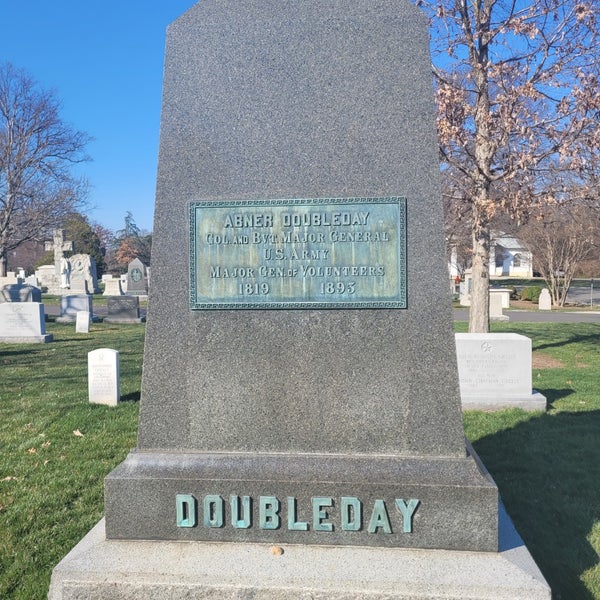

Note that the plaque on his tombstone

does not mention baseball.

It was also helpful that both Mills and Al Spalding, the owner of the team that became the Chicago Cubs, one of the pro game's 1st great pitchers, and the de facto Commissioner at the time, had also been friends of Doubleday's. It was also helpful that Doubleday died in 1893, and was, rather conveniently, no longer around to say, "Guys, the story isn't true."

The truth? Mills knew Doubleday rather well, and admitted that he'd never heard him claim to be the inventor of baseball. Doubleday's extensive journals mention baseball only once: In his duty as a quartermaster, he had requisitioned balls and bats for his soldiers, as there was a lot of down time between battles and they needed a diversion, and baseball had grown tremendously popular in the 1850s. His obituary in The New York Times didn't mention baseball at all. Based on the evidence we have, we don't know if Abner Doubleday liked baseball -- or if he ever even actually saw a game.

As for Abner Graves, he was old, and he was nuts. He apparently (accidentally?) burned down his own house, killing his wife. He spent a good chunk of his later years institutionalized. What's more, he would have been just 5 years old at what he claimed was the time of the game's invention. (I was 5 years old in 1975, when Carlton Fisk hit a certain home run, and I have absolutely no memory of having seen it then, not even on the news the next day.)

But here's the clincher, the part that makes the Doubleday story absolutely impossible: At the time, cadets at West Point were not permitted to leave the Academy grounds for any reason. If Doubleday had been in Cooperstown at any time in 1839, he would have been AWOL: Absent without leave. And there's no way he could have snuck off the grounds, gone almost 150 miles with no mode of transportation faster than a horse (there was no rail connection), gotten to Cooperstown, been involved with any sort of town event, gotten back, and snuck onto the grounds, without anybody noticing he was gone. It would have been days. He would have been expelled.

No, Doubleday did not invent baseball. Nor can it be called wholly the invention of Alexander Cartwright, who has been credited with writing the original rules for the game in New York in 1845 (and the evidence we have now suggests that other men wrote some of them), although it is worth nothing that Cartwright was elected to the Hall of Fame, while Doubleday has not been. Baseball wasn't invented so much as it evolved, and to name any one person its creator is, however well-intentioned, misleading.

New York's Madison Square Park, where Cartwright's Knickerbocker Club played intrasquad games, and Hoboken, home of the Elysian Fields where the Knickerbocker Club and other early clubs played, would each have been a better site for a monument to the game's invention, and for its Hall of Fame. But, as actor Donald Sutherland said in narrating a documentary for the Hall in the 1980s, "The decision of the umpire is final."

Stephen Corning Clark (1882-1960),

founder of the Baseball Hall of Fame

At any rate, in the 1930s, Stephen Clark, a Cooperstown-based businessman and a member of the old-money Clark and Corning families of New York State, wanted to drum up tourism in Central New York. He got the idea for the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1934, thinking of The Hall of Fame for Great Americans, at the Uptown Campus of New York University in The Bronx, now Bronx Community College. It's been mostly forgotten today, but it's still there, at 181st Street and Sedgwick Avenue, 2 blocks east of Ohio Field, NYU's old football complex. Metro-North to Morris Heights (University Heights station is closer as the crow flies, but not on foot), or 4 Train to Burnside Avenue.

Opening Day, June 12, 1939

Going In. The building itself is called the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum - or "MVSEVM," as they carved the name in as if it was Latin, which doesn't use the letter U. The address is 25 Main Street, between Pioneer and Fair Streets.

The main building opened on the alleged 100th Anniversary of the game's invention, June 12, 1939, with a lavish ceremony presided over by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and the Hall's founder, Stephen Clark, with 10 of the 25 men yet elected attending -- all of those still alive except for Ty Cobb, who arrived too late for the ceremony and the accompanying photo.

Top row, left to right: Honus Wagner, Grover Cleveland Alexander,

Tris Speaker, Napoleon Lajoie, George Sisler and Walter Johnson.

Bottom row: Eddie Collins, Babe Ruth, Connie Mack and Cy Young.

Sisler was the last survivor, dying in 1973.

Legend has it that Cobb got there late to spite Landis. It's not true: Transportation connections weren't what they would become, and Cooperstown, as I said, is hard to get to.

Since the Hall is, itself, a history display, I'll describe its exhibits in the usual category of "Team History Displays."

What was once "Farmer Phinney's Lot" was converted into Doubleday Field, which also opened in 1939. The main grandstand, behind home plate, looks it: Wooden benches instead of seats (metal or plastic), support poles, and a big roof. Grandstands were built down each foul line in 1960, and seating capacity is currently listed as 9,791.

That would make it one of the bigger minor-league parks, but the National Association, which governs minor league baseball, won't let anyone put a team there, because it doesn't have lights. So it hosts amateur games, such as high school and American Legion contests, plus the annual Hall of Fame Classic, as it has since 2010, as it hosted the Hall of Fame Game the day after each induction ceremony from 1940 to 2007 (plus an old-timers' game, with sides captained by Eddie Collins and Honus Wagner, the year before).

The official address is 1 Doubleday Court. Doubleday Court is a short street that extends south from Main Street, between Chestnut and Pioneer Streets. There is parking available -- it can also be used for visitors to the Hall, and costs $2.00 per hour or $14 for the whole day -- and the court has baseball-themed shops on it.

The field is natural grass, and points southwest, unusual for baseball fields. The fences are very close: 296 feet to the left field pole, a mere 336 feet to left-center, 390 to straightaway right, 350 to right-center, and 312 to right. I can find no record of who hit the longest home run there, or how far it went.

True story: When I first visited Cooperstown, on September 7, 1985 -- just as Pete Rose was getting ready to break the all-time hit record, so, naturally, that was the big topic of conversation in the Village -- there was a sign at the entrance to Doubleday Field, advertising a rugby match for Sunday, September 8. Rugby? At the birthplace of baseball? I thought that was weird, but, I figured, what the heck, I'd check it out.

But it rained overnight. The next day, at noon, right on schedule, I was there, and the weather was fine. Cliche alert: It was a beautiful day for baseball. But the little ballpark was locked up, the match canceled. Presumably, the field, not having access to a major league-quality drainage system, was still soaked. And I wondered if God thought using the "birthplace of baseball" for another sport was wrong -- particularly since rugby is, essentially, the father of "American football."

Food. Most museums have a cafeteria. The Hall of Fame does not. Nor does it allow food, drinks, or even gum chewing inside. (Nor smoking, nor chewing tobacco. This is not the old days, no matter how much history is inside.) They do have water fountains. But no cafeteria, or even vending machines. Nor does Doubleday Field. If you visit either, you'll have to soothe your munchies elsewhere.

Fortunately, Cooperstown has lots of places where you can do just that. None of them are chain restaurants: They officially keep them out. This also means no "big box stores": No Wal-Mart, no Target, no Home Depot. The closest thing they had to a chain store of any kind was a Newberry's "five-and-ten" that was next-door to the Hall, but it's long since gone.

If you must get a fast-food fix, about 4 miles south of the Village, outside of its jurisdiction, off State Route 28, is Cooperstown Commons, with a McDonald's, a Pizza Hut, a Subway, a China Wok (easily the closest Chinese restaurant to the Hall), a Crazy Cupz Frozen Yogurt, a Jive Cafe, and a Tops supermarket. It had a Tim Horton's, but it closed. Cooperstown Commons is flanked by a Holiday Inn Express and a Best Western.

The closest Burger King, Wendy's, Five Guys, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Taco Bell, Dunkin Donuts and Starbucks to Cooperstown are all in Oneonta, about 23 miles south on Route 28. The nearest Outback Steakhouse, Olive Garden and Red Lobster are in New Hartford, outside Utica, 41 miles northwest.

In the 1980s, 22 Chestnut Street, at the corner of Main, was a wonderful ice cream parlor called Sherry's. Now, it's Mel's at 22, and it's just a restaurant serving "American classics." No baseball theme. Not named for Mel Ott, Mel Harder, Mel Queen, Mel McGaha, Mel Stottlemyre, Mel Hall, or even Bob Melvin. At least it's not named for Mel of Mel's Diner on the late 1970s-early 1980s sitcom Alice. "Pickup!" Cooperstown Back Alley Grille is at 8 Hoffman Lane. Lake Front is a nautical-themed place at the Lake Front Hotel, at 8 Fair Street.

The following are all on Main Street, running from west to east, and a lot of them are coffee houses, perhaps designed to cater to people wondering where to find Starbucks or Dunkin Donuts: 157, Schneider's Bakery, across the street from Mel's; 149, Alex's Bistro; 136, Cooperstown Diner; 134, Mt. Fuji, a Japanese restaurant; 110, Sal's Pizzeria; 99, Hardball Cafe; 96, Nicoletta's Italian Cafe, a bit pricier than Sal's; 93, Doubleday Cafe; 92, Danny's Main Street Market; 73, Cooperstown Beverage Exchange; 69, Carmen Esposito's Italian Ice; 64, Toscana, another Italian restaurant. East of that, Main Street is occupied mainly by the Hall on the south side, and by Cooperstown's municipal stuff (Town Hall, the Post Office, etc.) on the north side.

The following are all on Pioneer Street, a block west of the Hall: 31, Stagecoach Coffee; 46, Pioneer Patio and Slices Pizzeria; 48, Sherman's Tavern; 49, Cooley's Stone House Tavern.

The Hall of Fame's main entrance

Team History Displays. In this case, the "team" is all of baseball. When you walk into the lobby, to the left is the ticket booth. To the right is the Museum Store -- meaning you don't have to pay to get in to shop there. Straight ahead is the Hall of Fame Gallery itself, however the Hall recommends that this not be your first stop.

They recommend that you go upstairs, and start on the 2nd floor. The initial display is the Locker Room, showing lockers for all 30 current Major League Baseball teams, including their home and away uniforms, caps, current yearbooks, and other items. This used to be in the basement, carpeted in Astroturf, but is now on the 2nd floor.

Leaving this "present day" exhibit, you "enter the time machine," beginning the history of the game, starting with the 19th Century, then the early 20th Century, and an exhibit honoring Babe Ruth. The "timeline," as they put it, moves on to displays about the Negro Leagues, women in baseball, and Latin Americans in baseball. The display moves into the modern era. These displays include uniforms, gloves, bats and balls from historic moments in the sport.

The 3rd floor contains an exhibit honoring ballparks, including the cornerstones from Ebbets Field and Shibe Park/Connie Mack Stadium. Moving on, there's a display honoring Hank Aaron. He and the Babe are the only 2 individual players so honored, Hank's display having replaced one honoring Casey Stengel. Next is One For the Books, a tribute to baseball's records; Autumn Glory, about postseason play; and Who's On First, a tribute to baseball in pop culture, with the Abbott & Costello routine of the same name on an endless loop.

(Contrary to an urban legend, Bud Abbott and Lou Costello have not been elected as Members of the Baseball Hall of Fame. Nor has any other entertainer, unless you want to say that all players are entertainers, or unless you want to count those players who have been actors (i.e. Don Drysdale on a number of 1960s TV shows, and Reggie Jackson appearing on a few 1980s shows and being brainwashed into trying to kill Queen Elizabeth in The Naked Gun). Abbott & Costello's film is played in the Hall of Fame, but that doesn't mean that they are "in the Hall of Fame." That term is reserved for elected Members.)

At this point, the Hall recommends that you return to the 1st floor, to see the Art of Baseball exhibit, an exhibit with memorabilia from the newest class of inductees, and, finally, the Hall of Fame Gallery itself.

It includes life-size wood-carved statues of Babe Ruth and Ted Williams, showing remarkable detail. I particularly noticed how real even the Babe's five o'clock shadow and his belt loops looked.

The Gallery covers 5,000 square feet, about 10 percent of the Hall's total exhibit space, with, at the moment, 317 plaques. (It will be 322 after this year's induction ceremony.) Assuming the rate of new inductions remains fairly stable, the Gallery has room for another 30 to 40 years' worth of plaques, so it will be around 2045 before they have to make a decision about what to do, space-wise.

At the back are The First Class, the 5 men who got the necessary 75 percent of the vote in the 1st election of 1936. In order: Ty Cobb, 98.2 percent (technically, if not officially, making him the 1st Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame, and his plaque is the one at the center of this X-shaped display); Babe Ruth and Honus Wagner, each with 95.1 percent; Christy Mathewson, 90.7 percent; and Walter Johnson, 83.6 percent. Then the players are shown in chronological order to the left of the viewer, wrapping around until the most recent inductees are to the right of The First Class.

Of the 50 men who got at least 1 vote in that 1st election, only Hal Chase, Johnny Kling, Lou Criger, Shoeless Joe Jackson, Nap Rucker, Bill Bradley (not the basketball player, he wasn't born yet), Kid Elberfeld and Billy Sullivan (not the New England Patriots' founder) have yet to be elected. Jackson, of course, is ineligible due to his gambling connection. So is Chase, for the same reason. As for the others, a case could be made for Rucker, but the rest fall way short.

Interestingly, active players were then eligible, and Rogers Hornsby, Mickey Cochrane, Lou Gehrig and Jimmie Foxx -- only 28 years old at the time, and with one of his 50-homer seasons still to come -- received votes. Ruth was also less than a year past his last game.

Eventually, the rules would be changed so that a player had to be retired for a full year (Joe DiMaggio had to wait 4 years, partly because some voters were not convinced that he wouldn't make a comeback), and finally for 5 full years. In other words, a player playing his last game in 2017 would wait through 2018, '19, '20, '21 and '22, and be eligible for election in the vote of January 2023.

The plaques are made by Pittsburgh foundry Matthews International, with the faces drawn since 1995 by a sculptor named Mindy Ellis, who, ironically, has only visited Cooperstown once, for the 1998 induction ceremony, at which she got a nice hand.

Their design has not changed since the initial induction ceremony in 1939: Each plaque is 15 1/2 inches tall, 10 3/4 inches wide, mounted on a 1 1/2-inch wooden frame, and weighs 14 1/2 pounds. The descriptive text on each runs 80 to 100 words, not including the listing of the teams for which the inductee played.

Some players, particularly earlier ones, are shown with no logo on their caps on their plaques. Some had their Hall-worthy contributions spread over more than one team. To use New York players as examples: While it was easy to say that Tom Seaver and Mike Piazza should have Met caps on their plaques, when they also did well elsewhere, it was harder for others. Reggie Jackson could have had the Oakland Athletics, but chose the Yankees, for whom he played "only" 5 years.

After his election in 1993, the choice was handed over to the Hall's research team. According to Hall president Jeff Idelson, "They'll look at a player's career numbers, and look at the impact. And quite honestly, it's usually a no-brainer. Then we have a conversation with the player, because we wouldn't do something unilaterally."

Still, Yankee star Dave Winfield's plaque has a San Diego Padres cap; Met legend Gary Carter, a Montreal Expos cap. Willie Mays ended his career with the Mets, but his cap is that of the San Francisco Giants, even though his most famous moment, his 1954 World Series catch, happened when the Giants were still in New York -- possibly to avoid confusion with younger fans who only know that curlicued interlocking NY as the Mets' logo, not the Giants', from which it was adapted.

Like Reggie, Catfish Hunter's accomplishments are divided between the A's and the Yankees, but his plaque has no logo. Wade Boggs won his only World Series with the Yankees, but he made his name with the Boston Red Sox, so his cap is Boston's. If Alex Rodriguez is ever elected, he'll probably have a Yankee cap. If Roger Clemens, who starred for 4 teams, but most notably for the Red Sox and the Yankees, is ever elected, the decision will likely be tougher.

There is a back door at the Gallery, and it leads to the National Baseball Library, or the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, as it's now known. It includes a bookstore, and an exhibit honoring the winners of the Ford Frick Award for broadcasters and the J.G. Taylor Spink Award for sportswriters -- considered "tantamount to election," even if the honorees are not actually shown in the Gallery.

The induction ceremony was held in front of the Library, on Fair Street, until 1991, before moving out to the Clark Sports Center.

Stuff. As I said, the Hall includes a Museum Store to the right of the lobby, and a Museum Bookstore in the Library wing behind the main building. Pretty much any book ever published about baseball is available, on order if not in person. The store sells all kinds of things, from equipment to replica jerseys, from team logo mugs to copies of the classic "Hartland statue" figurines, from videos to postcards with players' plaques on them.

There are lots of baseball-themed stores in town, such as Sandlot Kid Bat Company and Seventh Inning Stretch (both at 137 Main), Baseballism (131 Main), Cooperstown Bat Company (118 Main), Pioneer Sports Cards (106 Main), Yastrzemski Sports (75 Main), Mickey's Place (74 Main, named for Mantle), Hall of Shame Memorabilia (66 Main), Extra Innings (54 Main), and Cooperstown General Store (43 Main). Willis Monie Books (139 Main), while not strictly a baseball-themed joint, is a must-stop for anyone who likes to read.

During the Game. This category doesn't really apply in this case.

After the Game. Nor does this one.

Sidelights. The Heroes of Baseball Wax Museum is at 99 Main Street. It's not the shrine that the Hall is, but it's worth a look.

The Clark Sports Center, an athletic complex used by people from all over Central New York, has hosted the induction ceremony since 1992, due to having a lot more space. 124 County Highway 52 (Susquehanna Avenue), about a mile south of the Hall, across the Susquehanna River.

Cooperstown Junior-Senior High School is at 39 Linden Avenue, also about a mile south, but on the same side of the river as the Village. This is the closest thing to nearby teams in other sports. About 5 miles south is Cooperstown Dreams Park, which hosts an annual youth baseball camp on its 22 fields. That's right: 22 fields. It's like spring training and then some, but for kids. 4550 New York Route 28, in Milford.

There are many minor-league baseball teams in New York State. The one named for the alleged inventor of the game, the Auburn Doubledays, plays at Falcon Park in Auburn, 122 miles to the west. The closest team is the Tri-City Valley Cats, playing at Joseph L. Bruno Stadium in Troy, 75 miles east, at 80 Vandenburgh Avenue, across the Hudson River from Albany, representing both of those cities and Schenectady (hence, "Tri-City"), and successor to the old Albany Senators and the more recent Albany-Colonie Yankees.

Both of these teams play in the Class A New York-Penn League (formerly the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York, or PONY, League), along with the Staten Island Yankees and the Brooklyn Cyclones. However, nearby Oneonta, where the Yankees had a farm team from 1967 to 1998 at Dutch Damaschke Field (15 James Georgeson Avenue), no longer hosts pro ball, only a "summer collegiate league," like the Cape Cod League in Massachusetts.

The Utica Blue Sox, who played pro ball from 1939 to 1950, and again from 1977 to 2001, are also now in a Summer collegiate league, although, oddly, not the same one. Donovan Stadium at Murnane Field, 898 Rose Place, 42 miles northwest of Cooperstown.

A Met farm team since 1992, formerly known as the Binghamton Mets, or the B-Mets for short, but now the Binghamton Rumble Ponies, play in the Class AA Eastern League, their opponents including New Jersey's Trenton Thunder, a Yankee farm team. "Rumble Ponies"? Are the My Little Ponies challenging the Care Bears to a rumble? Anyway, they play at NYSEG Stadium, 211 Henry Street, 82 miles south of Cooperstown.

In Triple-A ball, in the International League, the Syracuse Chiefs are at NBT Bank Stadium, 1 Simone Drive, 81 miles northwest. They were a Yankee farm team from 1967 to 1977, with the Toronto Blue Jays from 1978 to 2008, and now with the Washington Nationals.

The Rochester Red Wings (St. Louis Cardinals 1929-60, Baltimore Orioles 1961-2002, now Minnesota Twins) are at Frontier Field, 333 Plymouth Avenue North, 165 miles west. And the Buffalo Bisons (a Mets farm team 1963-65 and 2009-12, now with the Blue Jays) are at Coca-Cola Field, 275 Washington Street, 237 miles west -- further from Cooperstown than New York City.

The closest MLB team, and easily the most popular team in town, is the Yankees: 189 miles. The most popular NBA team is the Knicks, and in the NHL the Rangers: 192 miles. The closest NFL teams are the Giants and Jets, 184 miles away; but the most popular NFL team in the area is the Buffalo Bills, 242 miles.

The closest major college football and basketball team is at Syracuse University, 94 miles. The closest MLS team is New York City FC, 189 miles, slightly closer than the New York Red Bulls at 194 miles. And if you're looking for a "pub" to watch your favorite "football club" play, you're probably out of luck: The closest place might be Field of Dreams Steakhouse, at Cooperstown Commons, 18 Commons Drive.

Lake Placid, site of the 1932 and 1980 Winter Olympics, is 182 miles northeast of Cooperstown, and 285 miles north of Midtown Manhattan.

In addition to the Baseball Hall of Fame, Stephen C. Clark founded the Otesaga Resort Hotel (half a mile northwest of the Hall, at 60 Lake Street, a.k.a. State Route 80), the Fenimore Art Museum (a mile and a half north, 5798 Route 80), and the Farmers' Museum (5775 Route 80, across from the Fenimore Museum).

The most famous musical location in New York State, with the possible exception of Madison Square Garden, was Max Yasgur's dairy farm, chosen as the site of the Woodstock Music & Art Fair, held on August 15 to 18, 1969.

The promoters wanted to hold it in the Ulster County town of Woodstock -- 104 miles north of Times Square and 85 miles southeast of Cooperstown -- because that was where Bob Dylan was living at the time, in the hopes that he would come. It's even been suggested that this was why anywhere from 400,000 to 500,000 people, about 3 times what the promoters had planned for, came. Many big stars came, and all became bigger stars as a result, but Dylan wasn't one of them.

But they couldn't get a permit from the Town of Woodstock, but they kept the name since it was already being publicized. They also tried and failed with the Town of Wallkill, also in Ulster County. They finally got a permit from the Town of Bethel, in Sullivan County, also in the Catskill Mountains.

But nobody planned for a crowd that ended up being about 3 times what they expected: The food, restroom and medical facilities (not helped by the "brown acid" version of LSD that was going around) were completely overwhelmed. And then there was the rain, which led to the mud, which led to the expression "dirty hippies." And while some performers' legends were made forever, others still say that it was the worst performance of their careers. Grace Slick of the Jefferson Airplane actually said that the music was better at the ill-fated Altamont concert in the Bay Area in December.

And there were 3 deaths: One overdose, one burst appendix, and one dummy went to sleep under a tractor for shelter, and it rolled over him. But, depending on who you talk to, there was anywhere from 1 to 3 births (no one has ever been able to track down "The Woodstock Baby," though), and God only knows how many conceptions and other children resulting from couples meeting at Woodstock.

There was no violence at Woodstock, unlike at Altamont. In contrast, a typical 1969 weekend in New York City saw 8 murders, or about 1 for every 1 million people. And there were about as many U.S. servicemen in Vietnam as there were people at the Woodstock festival, and a typical weekend there saw nearly 100 of them killed.

The farm has been converted into a performance stage again, an open-air amphitheatre seating 15,000, with a roof overhead, not unlike the Garden State (now PNC Bank) Arts Center in Holmdel, New Jersey. The Bethel Woods Center for the Arts is at 200 Hurd Avenue in Bethel, 92 miles south of Cooperstown, and 103 miles northwest of Midtown Manhattan.

The closest that Elvis Presley ever got to Cooperstown with a concert was the Onondaga County War Memorial, now the Oncenter War Memorial Arena, home of the NBA's Syracuse Nationals from 1951 to 1963, 80 miles away at 800 S. State Street in Syracuse, on July 25, 26 and 27, 1976. Even that is considerably closer than the Beatles got: Their closest shows were at Shea Stadium on August 15, 1965 and August 22, 1966, 196, miles away.

Several Presidents have connections to New York State. Martin Van Buren, Grover Cleveland, Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Roosevelt served as Governor of New York. The current Governor's residence, officially the New York State Executive Mansion, was home to Cleveland and both Roosevelts. 138 Eagle Street in Albany.

Van Buren lived most of his life at Lindenwald. 1038 Old Post Road, Kinderhook, Columbia County, 126 miles north of Times Square, 24 miles south of Albany, and 94 miles southeast of Cooperstown. He's buried at the Reformed Dutch Church in Kinderhook, 3 miles north of the house.

Millard Fillmore was born in what's now the Buffalo suburbs, and his birthplace is a historic site. 24 Shearer Ave, East Aurora, Erie County, 356 miles northwest of Times Square, 247 miles west of Cooperstown, and 19 miles southeast of Buffalo. Cleveland lived all around New York State, including in Buffalo where he was Mayor and Sheriff of Erie County before being elected Governor and then President, but no home of his in the State survives.

Both men have statues in front of Buffalo's City Hall, which is on Niagara Square, whose centerpiece is an obelisk, a memorial to William McKinley, assassinated in Buffalo in 1901. I discuss their sites in my Trip Guides for Buffalo.

Chester Arthur, born in Vermont but living most of his life in New York State, and sworn in as President in his an apartment in a Manhattan brownstone that still stands (123 Lexington Avenue), is buried at Albany Rural Cemetery. Cemetery Avenue in Menands, Albany County, 153 miles north of Times Square, 6 miles northeast of downtown Albany, and 75 miles east of Cooperstown.

Theodore Roosevelt lived most of his adult life on Long Island. Franklin Roosevelt's home and Presidential Library are between U.S. Route 9 (the Albany Post Road) and the Hudson River. 4079 Albany Post Road, Hyde Park, Dutchess County, 85 miles north of Midtown Manhattan, 70 miles south of Albany, and 116 miles southeast of Cooperstown.

Two Presidents were graduates of the U.S. Military Academy: Ulysses S. Grant and Dwight D. Eisenhower. The Visitors' Center is at 2107 New South Post Road, in West Point, Orange County, 50 miles north of Midtown Manhattan (Adirondack Trailways can get you there), and 146 miles southeast of Cooperstown.

Despite the Hall of Fame's role in baseball lore, there haven't been many TV shows or movies set there. A 1999 episode of Everybody Loves Raymond saw the brothers Ray and Robert Barone (played by Ray Romano and Brad Garrett, respectively) get kicked out of the Hall, where an autograph session was being held for members of the 1969 Mets. Ray Barone was a sportswriter who'd written an unkind column about Tug McGraw, one of the Miracle Mets who played himself.

The ABC soap opera General Hospital and its now-defunct spinoff Port Charles are set in Port Charles, hits about whose location suggest that it's a stand-in for Rochester, 174 miles northwest of Cooperstown.

As far as I know, the only movie to film inside the Hall of Fame building is A League of Their Own, which began and ended there in what was then the film's present day, 1992, before going back to the World War II season of 1943. Although the W.P. Kinsella novel Shoeless Joe has Ray Kinsella and J.D. Salinger visiting the Hall, the film version, Field of Dreams, does not feature a visit by Kevin Costner's Ray and James Earl Jones' fictional counterpart to Salinger, Terence Mann.

*

Every baseball fan should visit the Baseball Hall of Fame. And if you need to bring someone with you, and they're not interested in baseball, Cooperstown, New York is a charming little town with lots to see for someone, whether they're into baseball or not.

Like the man said, You don't stumble upon Cooperstown by accident; you have to want to go there. Whether you like baseball or not, you should want to go there.

No comments:

Post a Comment