By 1971, he was 44 years old, and those Dodgers were in or approaching their 50s. Two of them died the next year: Gil Hodges from a heart attack in April and Jackie Robinson from diabetes in October.

Brooklyn has always had a separate identity. From its incorporation in 1834 until the consolidation of "Greater New York" that took effect on January 1, 1898, it was a separate city. When the referendum to consolidate happened in 1897, what became the other 4 Boroughs all voted for it in a landslide, but in Brooklyn, the Yes side won in a squeaker.

Brooklyn had half of the Brooklyn Bridge (they seemed to care less about the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges that followed) and the Brooklyn Navy Yard at one end, Coney Island at the other, and Prospect Park, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Dodgers in the middle.

The Dodgers moved to Los Angeles after the 1957 season. The Pentagon closed the Navy Yard in 1964. That same year, also the year the Drifters' song "Under the Boardwalk" evoked classic Coney Island, Steeplechase Park closed. It was the last of the old Coney Island amusement parks, leaving only the more recently-opened Astroland, which is still going.

By that point, the Irish, Italian, Polish and Jewish communities that made Brooklyn the Brooklyn of memory had shrunk, because many of those people had taken advantage of post-World War II opportunity to move to better surroundings in Staten Island, Queens, Long Island, Westchester, Connecticut and New Jersey. (When I grew up in East Brunswick, there were a lot of ex-Brooklynites there.)

And taking their places were poor blacks and Hispanics who couldn't afford to keep the place properly maintained. Brooklyn became a crime-ridden shadow of its former self. And memories of the old Coney Island and the Dodgers, and tributes thereto, made Brooklyn itself a symbol of all that once was good to millions of people, the majority of whom never set foot in the State, let alone the City, of New York.

As a result, even those of us who weren't born yet in 1957 (i.e. most of the people reading this) "remember" Brooklyn, and "remember" the Brooklyn Dodgers, and many of us wish they'd never moved.

The New York Giants, who moved to San Francisco after 1957, going to California at the same time as the Dodgers, never got that tribute. No one wrote their Boys of Summer. The Yankees had Peter Golenbock write Dynasty, which, as he stated in the introduction to the 1st edition in 1975, was an explicit response to Kahn's book, saying that you could remember a team that seemingly always won with as much fondness as one that seemingly had heartbreak in mind.

(Kahn is now 88 years old, while Golenbock is 69. Both have written eloquently about baseball, particularly New York baseball, many more times. They have even flipped subjects: Golenbock wrote Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers, while Kahn wrote October Men about the 1977 and '78 Yankees.)

There have been books about the baseball team that gave the still-here football team its name. But those books were mostly well after The Boys of Summer and Dynasty. But the best writing about them was probably published before the move: Arnold Hano's A Day In the Bleachers, which came out the following spring, 1955. (Hano, like Kahn and Golenbock, is still alive at this writing, at age 93.)

As a result, we have 2 whole generations of baseball fans, and are beginning a 3rd, who know the New York baseball Giants only for Bobby Thomson's walkoff home run in the 1951 National League Playoff, and Willie Mays' catch in Game 1 of the 1954 World Series, because "The Shot Heard 'Round the World" and "The Catch" have been played on TV a thousand times, and are easily available on YouTube. We've seen both plays so many times we can recite Russ Hodges' call of the former and Jack Brickhouse's of the latter. Dusty Rhodes' walkoff homer came in the same game as Mays' catch, essentially deciding the Series (after all, Mays' catch didn't win the game, though it did preserve the then-current tie score), and it's practically an afterthought.

Art project recreating Mays' catch and throw,

at the Polo Grounds Towers.

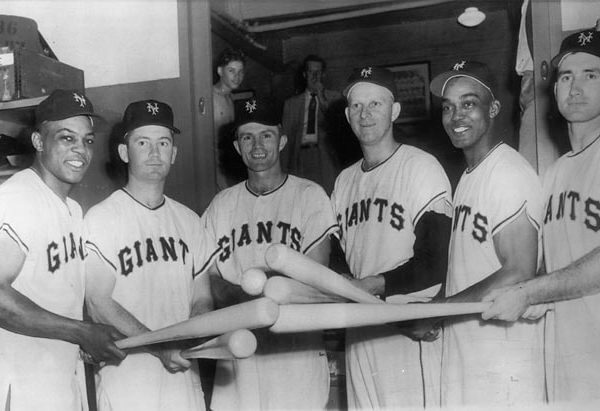

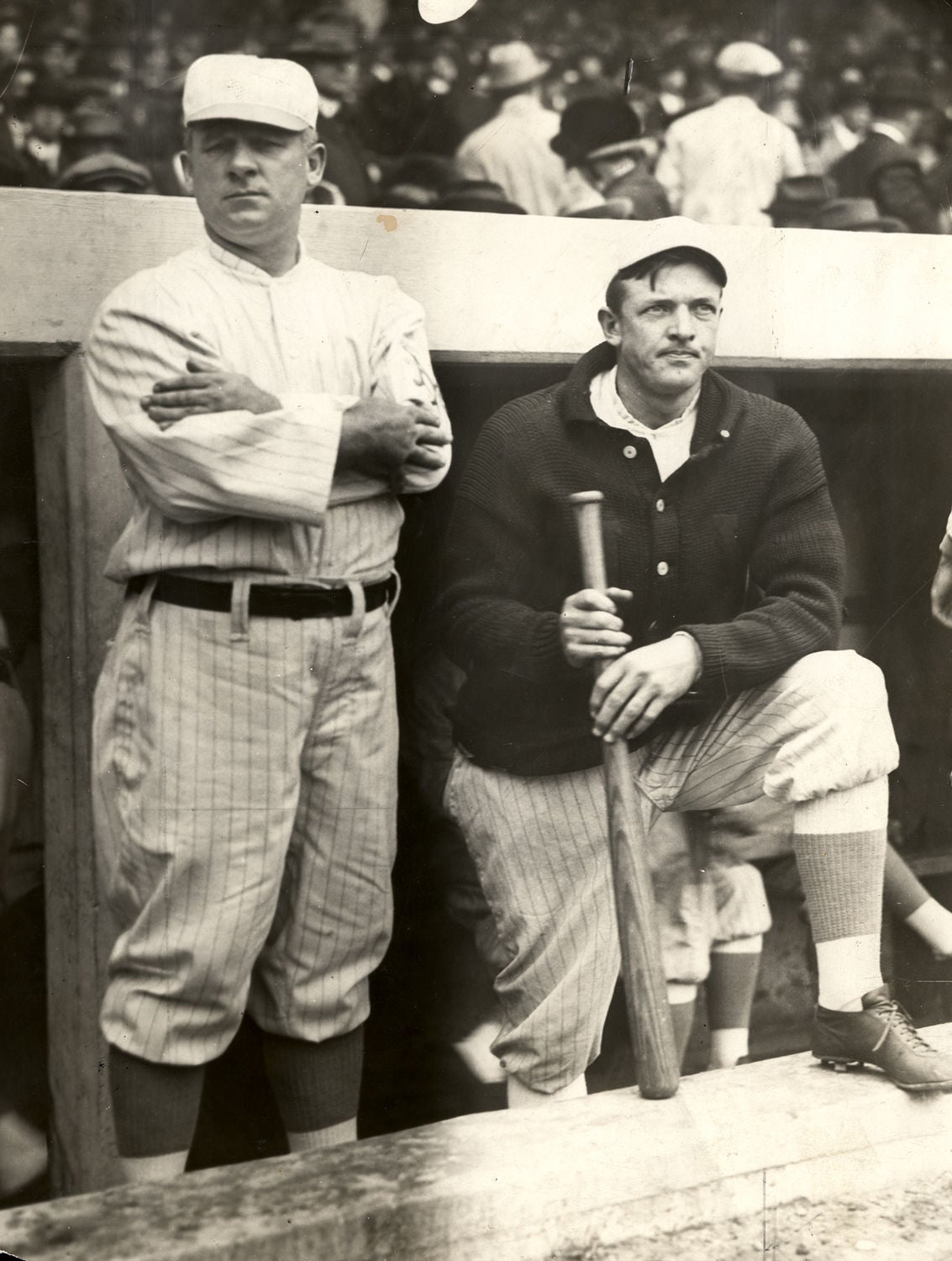

Roger Connor, Amos Rusie, John McGraw, Christy Mathewson, Joe McGinnity, Roger Bresnahan, Mel Ott, Bill Terry, Carl Hubbell? Those guys played 80 to 130 years ago. It might as well have been a thousand. Terry and Hubbell died in 1988, meaning they were alive at the same time as Beyonce, the 3 older Kardashian sisters. and 1 of the Jonas Brothers. But, to today's teenagers, they might as well have been contemporaries of Marco Polo or Charlemagne, names they may have heard, but know only "one-line biographies," if that.

McGraw and Mathewson

The baseball Giants played their last New York home game over 58 years ago; their last New York World Series, they won over 61 years ago. Your father or grandfather might have rooted for them, but they are forgotten, even if Mays is still alive. (Monte Irvin just died, and Bobby Thomson died in 2010.)

And they shouldn't be. From their 1883 establishment to their 1957 move, they won 17 National League Pennants (and had a few other near-misses), and won postseason series against the champions of the other major league then in place 7 times, including 5 World Series. Until the 1927 Yankees, led by Babe Ruth, established themselves as "Murderers' Row," the Giants were the baseball franchise.

And they left.

*

The worst part is, it didn't have to be that way. Look at the reasons ESPN gave in their "The Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame Walter O'Malley for Moving the Dodgers to Los Angeles":

5. Horace Greeley. Greeley, a 19th Century New York newspaper publisher, never said, as has been attributed to him, "Go west, young man!" But he was a proponent of America's westward expansion. His name stands in on this list for all those who've said America's future was in its west, and its past was in its east. That seemed very true in the 1950s, and Dodger owner Walter O'Malley sure came to believe it.

4. William Levitt. His Levittown construction launched the exodus of so many Brooklynites and Queensians to Long Island, taking the Dodgers' fan base with them. This was aided by the G.I. Bill of Rights, allowing veterans easier housing loans, to get out of the ghettos, some of which were white at the time. Driving to Ebbets Field was next to impossible.

This is why O'Malley wanted to build a new Dodger stadium across from the Long Island Rail Road terminal: So people could drive to their local LIRR station and then take the train in. He didn't get it, but, eventually, Nets owner Bruce Ratner did, and thus was born the Atlantic Yards project and the Barclays Center.

3. Milwaukee. The Braves had left Boston to the Red Sox, and did great in Milwaukee. Their modern stadium (modern for the time) and gigantic parking lot showed O'Malley that he couldn't continue at tiny, antiquated Ebbets Field with its minimal parking. He needed a new ballpark, either in Brooklyn or out of it.

2. Los Angeles. It had already been considered by teams looking to move, so if the Dodgers hadn't moved there, somebody would have. Or it would have gotten an expansion team. Which it got, anyway: The Angels. It has proven to be a good market for baseball: Even when the Bums and the Halos have struggled on the field, they've usually had good attendance.

1. Robert Moses. The man in charge of construction for not just the City, but the State wouldn't condemn the property necessary to build the domed stadium O'Malley wanted. He was willing to build them a multipurpose stadium in Queens, but O'Malley didn't want Queens: He either wanted Brooklyn, or out of the City entirely.

ESPN didn't render a verdict, but they certainly implied O'Malley was Not Guilty.

My verdict: Guilty, which you can read here, in one of the earliest posts I ever wrote for this blog.

Moses and his Queens project, which became Shea Stadium, are the key, at least from the Giants' perspective. Suppose Giants owner Horace Stoneham had invited Moses to Game 1 of the 1954 World Series -- the game illuminated by Mays' catch, won by Rhodes' homer, and chronicled by Hano's book.

Maybe Moses wouldn't have become a baseball fan, but he would have seen how the fans reacted to one of the most amazing games in baseball history. Stoneham, who said after the Giants' last home game on September 29, 1957, "I feel bad for the kids, but I haven't seen too many of their fathers lately," could have told Moses, "I need a new ballpark. Help me build something for these wonderful fans, so they don't have to go to an outdated stadium in a bad neighborhood."

The Giants could have hosted Opening Day 1958 not at Seals Stadium in San Francisco, but at the stadium we came know as Shea. And while a team playing in Queens calling itself the Brooklyn Dodgers would have been wrong, there would have been absolutely nothing wrong with a team called the New York Giants playing in Queens, any more than it was wrong, in the history we know, for the Mets to play there under the New York name.

(Of course, if either or both of the New York National League teams had stayed, there never would have been a New York Mets. An expansion franchise would still have been put in the NL in 1962, but it would have been elsewhere. Possibly San Francisco. It would also have given the fledgling American Football League more credibility if their New York franchise, the Titans, who became the Jets in 1963, could have played in a 60,000-seat stadium from that start, instead of in the crumbling old Polo Grounds.)

And, just as the Dodgers needed only 2 years to win a Pennant in L.A., the Giants rebounded from a poor last season in New York to a good 1st one in San Francisco. For their 1st 15 years in the Bay Area, they did well both on the field and at the box office. The young talent they had coming up -- Orlando Cepeda, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry, all of whom joined Mays in the Hall of Fame -- would have become New York baseball superstars.

But Stoneham wanted to get out of the Polo Grounds. The Giants' top farm team was the Minneapolis Millers, and Metropolitan Stadium had just been built for them in suburban Bloomington. Before O'Malley told Stoneham, "Let's go to California together," Stoneham was planning to open the 1958 season as the Minnesota Giants.

If he had just talked to Moses, and hung on just a little longer... Who knows? There could have been Subway Series with the Yankees in 1962 and possibly other times. The Giants nearly won the NL Western Division in 1969, so maybe they, not the Mets we know, could have beaten out the Chicago Cubs in the NL East, and produced New York's "Miracle of '69." And maybe they still would have won the 2010, '12 and '14 World Series, giving New York more titles in those 5 seasons than the Mets have given us in 54 seasons.

And the only games they would have had to play in Candlestick Park would have been away games, home games for a San Fran expansion team. Or maybe, whenever San Fran got its own team, they would have agreed to a different plan, and gotten a downtown ballpark much sooner than 2000, when the stadium now called AT&T Park opened. And the 49ers could have played at Stanford until a renovated Kezar Stadium opened, making both Candlestick and the new Levi's Stadium unnecessary. And, not having to play in Candlestick, maybe both the 49ers and this hypothetical expansion baseball team would have been more comfortable, and won more in San Francisco, than the 49ers and baseball Giants actually did.

It is very possible that both New York and San Francisco would have been better off if the Giants had never moved.

*

At any rate, that's the case for the prosecution. What's the case for the defense?

Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame the New York Giants for Moving to San Francisco

5. Demographics. As I said earlier, New York (and this was true for nearly every major city in America at the time) was seeing a massive outflux into its suburbs, making it harder for fans living there to get back into the City to see live games. Many stuck to their living rooms and their new TVs.

Midtown Manhattan, 1957, the year of the moves.

As I said in my post about the Top 10 Myths About the 1950s, the great American middle class was in the early stages of great growth, so fans couldn't afford to go to multiple games a year unless they were rich. Attendance was not as good then as it became in the 1960s, '70s, and beyond. It was far below New York baseball's peak year of 2008, the last year of the old Yankee Stadium and Shea:

From the first postwar season of 1946, to the last season in Brooklyn in 1957, the Dodgers averaged just 16,800 fans per home game, in a ballpark, Ebbets Field, that seated 31,497. That's just 53 percent of capacity...

In 1949, the Dodgers averaged 20,945 fans -- and never topped 17,000 as a seasonal per-game average again until 1958, their first year in Los Angeles (the novelty factor taking hold there). That overall 1947 total was 1,807,526, and while they got at least 1 million total fans every year after World War II, in 1954, '55 (the World Championship season) and '57, they just got past the million mark. In contrast, in the 56 seasons that the Dodgers have played in Los Angeles, only 5 times, and not at all since 1970, have they failed to top that 1947 Brooklyn peak.

The Giants did even worse: Their per-game average at the 55,987-seat Polo Grounds from 1946 to 1957 was 13,642 -- just 24 percent of capacity. In other words, the average Dodger crowd and the average Giant crowd combined, 30,442, would not have sold out Ebbets Field, let alone the Polo Grounds. Double it, and it wouldn't have filled the pre-renovation original Yankee Stadium.

And how do these figures compare to the team then frequently described as "the lordly Yankees"? They averaged 24,063 from 1946 to 1957 -- over 10,000 more than the Giants and 7,000 more than the Dodgers, but still not great.

Theoretically, New York has the population base to economically support 3 Major League Baseball teams today. It did not have that in the 1950s. Two would have been better then, just as it is now.

4. Walter O'Malley. Maybe if he'd avoided Stoneham, the Giants would still have moved to Minnesota. But he needed another team in California to help him cut down on travel costs. If not for O'Malley, the Giants might not have stayed in New York, but they certainly wouldn't have gone to San Francisco.

3. Surroundings. It wasn't just that the 1911 edition of Polo Grounds was past its 40th Anniversary and not in good shape, or that Stoneham didn't have the money to get it back into good shape. It was the neighborhood.

The Polo Grounds was at the northern end of 8th Avenue (now known as Frederick Douglass Boulevard north of Central Park), at 155th Street, across from what's now Holcombe Rucker Park, where the eponymous, legendary basketball tournament is held. To the east is the Harlem River, where no people live. To the south is Harlem. To the north and west is Washington Heights. Both of those neighborhoods had already begun to descend into morasses of crime, drugs and violence. There would have been no benefit to the Giants' staying put.

The football Giants had already moved across the river to Yankee Stadium in 1956, and it was the neighborhood as much as the stadium that made them switch. (The South Bronx' decline, while underway, took a few more years to be widely noticed.)

Ironically, of the 3 New York baseball teams at the time, the Giants had by far the most parking, as you can see in this photo (which has been colorized, but accurately). But who'd want to park their car there?

2. San Francisco. Already a city with a proud Pacific Coast League tradition, they embraced the Giants wholeheartedly. Except for Mays: They viewed him as a New York player, while Cepeda, McCovey and the rest were "San Francisco's boys."

As Frank Conniff of the New York Journal-American put it after the Soviet premier's 1959 visit to America, "Some city: They boo Willie Mays and cheer Khrushchev." (But then, like all Hearst Syndicate papers were at that point, the Journal-American was a right-wing rag, and any chance to slam liberal San Francisco was pounced upon.)

If the Giants had to move anywhere, Minnesota might have been a good choice, and San Francisco was also a good one. The problem was never the city, it was the ballpark: Candlestick was a bad stadium in a bad location. And not just because of the weather: It was at the southeastern edge of the city, away from downtown and a mile from the closest public transportation. San Francisco, then as now, had a great public transportation system, but you had a hard time using it to get to The 'Stick.

The Giants had attendance problems in the 1970s and '80s, but that was because the stadium was bad, not because the city didn't love its baseball. They've sold out AT&T Park regularly since it opened in 2000 (as Pacific Bell Park), even when the Giants were losing. San Francisco is a good baseball city.

Of course, so is New York. Where, in the 1950s, construction projects were ruled by...

1. Robert Moses. He was willing to offer the Dodgers his Flushing Meadow stadium. Why didn't he offer it to the Giants? If he had, the Giants might have been the team moving from the stadium we knew as Shea into Citi Field in 2009, and played the 2010, 2012 and 2014 World Series there. And the historical difference between the Yankees and the National League team in New York would be much smaller, and not a gigantic joke, like it is between the Yankees and the Mets that actually happened.

VERDICT: Not Guilty. I don't blame the Giants for taking the option of moving to San Francisco. It was not clear at the time that staying in New York would have been for the best. With over half a century of hindsight, it's still not clear that staying would have been for the best.

How the Giants handled it, including the building and occupation of Candlestick Park, is another matter. They totally screwed themselves, and their new fans, with that. But moving to San Francisco was understandable then.

But it still left us with the Mets. Then again, who knows: Maybe if the Giants had stayed, their fans, with a good history behind them instead of a lousy one, would be even more obnoxious, and just as stupid, as Met fans have been.

3. Surroundings. It wasn't just that the 1911 edition of Polo Grounds was past its 40th Anniversary and not in good shape, or that Stoneham didn't have the money to get it back into good shape. It was the neighborhood.

The Polo Grounds was at the northern end of 8th Avenue (now known as Frederick Douglass Boulevard north of Central Park), at 155th Street, across from what's now Holcombe Rucker Park, where the eponymous, legendary basketball tournament is held. To the east is the Harlem River, where no people live. To the south is Harlem. To the north and west is Washington Heights. Both of those neighborhoods had already begun to descend into morasses of crime, drugs and violence. There would have been no benefit to the Giants' staying put.

The football Giants had already moved across the river to Yankee Stadium in 1956, and it was the neighborhood as much as the stadium that made them switch. (The South Bronx' decline, while underway, took a few more years to be widely noticed.)

Ironically, of the 3 New York baseball teams at the time, the Giants had by far the most parking, as you can see in this photo (which has been colorized, but accurately). But who'd want to park their car there?

2. San Francisco. Already a city with a proud Pacific Coast League tradition, they embraced the Giants wholeheartedly. Except for Mays: They viewed him as a New York player, while Cepeda, McCovey and the rest were "San Francisco's boys."

As Frank Conniff of the New York Journal-American put it after the Soviet premier's 1959 visit to America, "Some city: They boo Willie Mays and cheer Khrushchev." (But then, like all Hearst Syndicate papers were at that point, the Journal-American was a right-wing rag, and any chance to slam liberal San Francisco was pounced upon.)

Downtown San Francisco, 1958

If the Giants had to move anywhere, Minnesota might have been a good choice, and San Francisco was also a good one. The problem was never the city, it was the ballpark: Candlestick was a bad stadium in a bad location. And not just because of the weather: It was at the southeastern edge of the city, away from downtown and a mile from the closest public transportation. San Francisco, then as now, had a great public transportation system, but you had a hard time using it to get to The 'Stick.

The Giants had attendance problems in the 1970s and '80s, but that was because the stadium was bad, not because the city didn't love its baseball. They've sold out AT&T Park regularly since it opened in 2000 (as Pacific Bell Park), even when the Giants were losing. San Francisco is a good baseball city.

Of course, so is New York. Where, in the 1950s, construction projects were ruled by...

1. Robert Moses. He was willing to offer the Dodgers his Flushing Meadow stadium. Why didn't he offer it to the Giants? If he had, the Giants might have been the team moving from the stadium we knew as Shea into Citi Field in 2009, and played the 2010, 2012 and 2014 World Series there. And the historical difference between the Yankees and the National League team in New York would be much smaller, and not a gigantic joke, like it is between the Yankees and the Mets that actually happened.

Robert Moses, 1959, during the interregnum between

the Dodgers' and Giants' moves and the Mets' arival

VERDICT: Not Guilty. I don't blame the Giants for taking the option of moving to San Francisco. It was not clear at the time that staying in New York would have been for the best. With over half a century of hindsight, it's still not clear that staying would have been for the best.

How the Giants handled it, including the building and occupation of Candlestick Park, is another matter. They totally screwed themselves, and their new fans, with that. But moving to San Francisco was understandable then.

But it still left us with the Mets. Then again, who knows: Maybe if the Giants had stayed, their fans, with a good history behind them instead of a lousy one, would be even more obnoxious, and just as stupid, as Met fans have been.

No comments:

Post a Comment