This has gone down as one of the most lopsided trades in baseball history. While Spring and Toth turned out to be all but meaningless to the Cards, the addition of Brock is widely credited as being the catalyst to their 1964 Pennant run, and to winning 3 of the next 5 National League Pennants. Brock went on to set records for stolen bases in a season and in a career, and still holds the NL records in each case. He also collected over 3,000 hits, and is in the Hall of Fame.

Clemens didn't do much for the Cubs. Nor did Shantz, once a very good pitcher, now at the end of a fine career. The key was Broglio, who went 4-7 for the Cubs the rest of the way in 1964, went 7-19 total after the trade, and was finished just 2 years later -- at which point Brock had 13 more seasons in him.

A typical dumb Cub trade, one that deserves to be remembered as one of the worst ever? Not so fast.

The Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame the Chicago Cubs for Trading Lou Brock for Ernie Broglio

5. Jimmy Stewart. No, not the It's a Wonderful Life actor, although he did play a real-life baseball player in the 1948 film The Stratton Story. This Jimmy Stewart was a rookie 2nd baseman, born the same week as Brock in June 1939, a fellow black Southerner, from Alabama as opposed to Brock's Louisiana.

He, not Brock, was the Cubs' leadoff hitter in 1964, taking the place of Ken Hubbs, who was killed in the off-season in a plane crash. He stole 10 bases for the Cubs that year, and 13 the next, and had a good glove. The Cubs probably thought they had a 2nd baseman and leadoff man for the next 10 years, and that they didn't need a player like Brock.

By 1967, however, Stewart had proven to be an awful hitter, and was traded, with Glenn Beckert taking his place at 2nd base, and shortstop Don Kessinger his place at the top of the order. He did revive a bit later, and helped the Cincinnati Reds win the Pennant in 1970.

4. The Styles of the Ballclubs. Although, in 1962, he famously hit a ball into the center-field bleachers at the Polo Grounds in New York -- one of only 4 players ever to do so, the others being Hank Aaron, Joe Adcock, and Luke Easter in a Negro Leagues game -- Brock wasn't really a power hitter, having hit 20 in 1,308 plate appearance for the Cubs before the trade.

Because of the wind blowing out at Wrigley Field, the Cubs have perennially been built around power hitters, and Brock simply wasn't looking like a power hitter hitter. Because of the wind blowing in at Wrigley half the time, this strategy wasn't especially smart, and they should instead have been built around pitching.

Brock ended up hitting 149 home runs in his career, peaking at 21 and only that once topping 16. Even so, the Cubs already had Ernie Banks, Billy Williams, Ron Santo and Billy Cowan in their lineup. Power was not a problem for them.

In contrast, for about 90 years now, the Cardinals have been built around pitching, defense, contact hitting and baserunning. Speed, speed and more speed was a Redbird hallmark at Sportsman's Park and Busch Memorial Stadium, long before Whitey Herzog came along.

True, the Cards have had some big boomers, such as Rogers Hornsby, Joe Medwick, Johnny Mize, Stan Musial, Roger Maris at the end of his career, Jack Clark, and more recently Albert Pujols and Matt Holliday.

But when you think of offensive players for the St. Louis Cardinals, you think of "Gashouse Gang" players like Pepper Martin, the scrappy, hard-charging "Wild Hoss of the Osage"; and guys who followed in that tradition. Guys like Enos Slaughter and Marty Marion.

At the time Brock arrived, they had Curt Flood, Julian Javier, and the veteran former MVP winner Dick Groat. As Groat faded, Bobby Tolan took his place on the basepaths (if not in his exact position). Later on, there were the Herzog boys such as Ozzie Smith, Willie McGee and Vince Coleman.

(Oddly enough, no Cardinal player last season stole more bases than Jon Jay's 10, and they won the Pennant anyway. Nor did they need more than the 11 of Tyler Greene in 2011, or the 11 of So Taguchi in 2006, to win the whole thing. But they were still a contact-hitting, great defense and solid pitching team.)

An exception to this was their 1997-2001 interlude with Mark McGwire, and they paid for it by being a very mediocre ballclub, although they did reach the NL Championship Series in 2000, though this proves my point because McGwire was hurt a lot that season.

Lou Brock was not a good stylistic fit for the Cubs. He was an excellent one for the Cardinals.

3. Billy Williams. Brock's only real position was left field, and the Cubs already had an All-Star, a future Hall-of-Famer, in left field. A prospect is not going to force someone like that out.

Perhaps, if Brock (or Williams) had been taught how to play center field, instead of having a parade of not very good players there, the Cubs might have put themselves in better position to win the 1969, 1970 and 1973 National League Eastern Division titles (the only times they got relatively close to postseason play from 1945 to 1984).

Indeed, one of the reasons cited for the Cubs' 1969 September Swoon was the defense of center fielder Don Young. Brock wasn't going to move the fine-fielding Curt Flood out of center field in downtown St. Louis, but he would have been a better choice for the North Side of Chicago than Young.

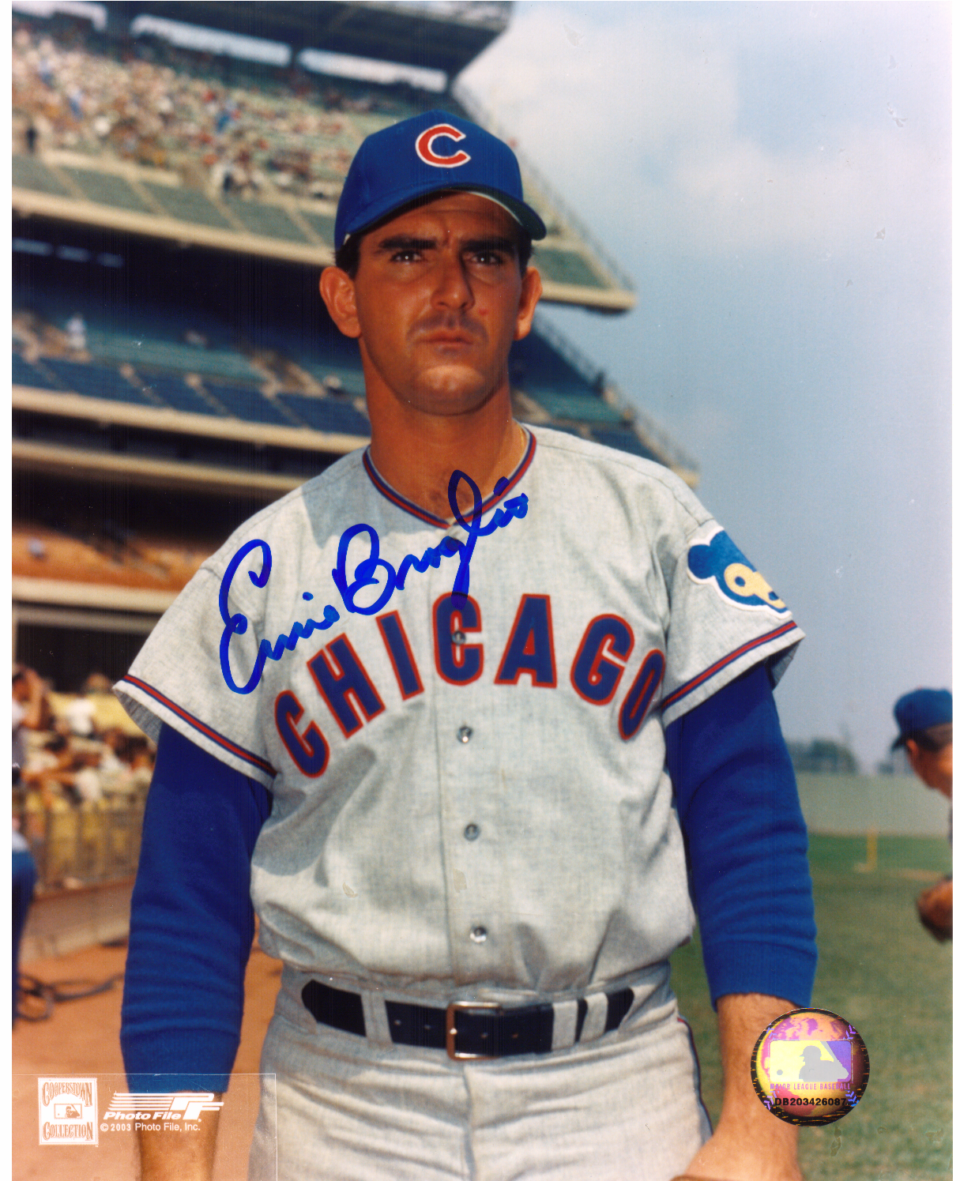

2. Ernie Broglio. At the time of the trade, Broglio was 27 years old, almost 28, and had already won 70 games in the major leagues, against just 55 losses, all for the Cardinals. He led the NL with 21 wins against just 9 losses for a rather ordinary Card team in 1960, finishing 3rd in the voting for the Cy Young Award behind Vernon Law of the World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates and future Hall-of-Famer Warren Spahn of the Milwaukee Braves -- and remember, that was an award for the most valuable pitcher in both leagues at the time. The year before the trade, 1963, he went 18-8 for an improving Cardinal team.

Broglio didn't tell anyone at the time, but he was suffering from an injured elbow since the 2nd half of the 1963 season. He had to have his ulnar nerve reset after the 1964 season. If the Cubs had known about his injury, chances are, they wouldn't have traded for him.

"We didn't know a lot about Lou Brock. That shows you what ballplayers know," said Tim McCarver, who was the Cardinals' catcher throughout the 1960s. "But we all loved Ernie. How could you not? You couldn't not love him. We felt bad for Ernie, and were upset that he was leaving. We didn't want him to leave."

Wait a minute: Tim McCarver was one of the smartest guys in baseball (just ask him, he'll tell you) -- and he didn't know a lot about Lou Brock in June 1964? How could that be?

I will tell you how that could be:

1. Lou Brock. This is what his career statistics looked like on June 15, 1964, at which point he was 3 days away from turning 25, a point at which most guys who end up becoming baseball stars have already begun to show that they will do so:

BA .257

OBP .306

SLG .383

OPS+ 88

Hits 310

2B 52

3B 20

HR 20

RBI 86

Runs 183

SB 50

All-Star appearances 0

Postseason appearances 0

Do those numbers say "Future Hall-of-Famer" to you? Because they sure don't say that to me. But check out his numbers for his entire career:

BA .297

OBP .347

SLG .414

OPS+ 109

Hits 3,023

2B 434

3B 121

HR 149

RBI 814

Runs 1,610

SB 938

All-Star appearances 6

Postseason appearances 3

Would Brock have had career stats like those if he'd stayed with the Cubs? There's no way to know. But then, there was no way to know that an additional 2,700 hits and nearly 900 stolen bases were coming after June 15, 1964.

In case you're wondering, although he was generally regarded as a good fielder, he never won a Gold Glove.

Why didn't the Cubs organization -- or, to be fair, the Cardinals' players -- see that coming? It was 1964. There was no ESPN to show you highlights of every game played on a given day. There was no Internet to give you freshly-updated stats within seconds. In those days, doing research on a baseball player consisted of doing 3 things: Reading The Sporting News, waiting for a player to appear on TV on The NBC Game of the Week, or getting off your ass and going to watch him play live.

And even TSN didn't have the kind of specialized stats we have now: On-base percentage was known, but OPS+ wasn't; nor was WAR, nor VORP. Strikeouts were considered the worst thing a player could do at the plate (and Brock struck out 122 times the year before the trade, a big number for the JFK years, and he would top that total 3 times). Grounding into double plays was not seen as worse, though it should have been, since it creates 2 outs instead of 1.

They didn't break things down like how a player does against lefties and righties, in day or night games, at home or on the road, in specific innings, with a particular set of baserunners, in ballparks with close or distant fences. Nor did they break it down as to how a batter did on various counts, or against which pitches: Fastballs, curveballs, changeups, what have you.

There was the occasional manager who kept notes, but for most, when they said they did things "by the book," they were speaking figuratively. Most operated on experience and hunches, like Casey Stengel. The days of Earl Weaver's printouts, Tony LaRussa's laptop and Joe Girardi's binder were all in the future.

VERDICT: Not Guilty. There was no way to tell that Lou Brock was going to become a Hall-of-Famer. And Ernie Broglio looked like a good acquisition. That he wasn't one wasn't his fault, and it wasn't really the Cubs' fault, either.

*

Lou Brock will turn 75 this week, and is one of baseball's elder statesmen -- he is, effectively, the Cardinals' ambassador and greatest living player after the recent death of Stan Musial. He and his wife are ordained ministers, and they still live, preach and go to games in St. Louis.

Ernie Broglio is 78, and is retired and living in the East Bay area of Northern California, from whence he came. He holds no bitterness about being compared to Brock, or about how his baseball career ended."We became pretty good friends after the trade," Broglio said in an interview for an anniversary article in today's Chicago Sun-Times, "just because there was so much constant talk about it. But Lou was always a good guy. He wasn't a bragger. He'd just get on the field and do the job, steal bases, hit for a high batting average. That's why he's in the Hall of Fame, because of that attitude that he had."

It sounds as though Broglio has a good attitude about it, too.

UPDATE: Ernie Broglio died on July 16, 2019, at the age of 83. Lou Brock died on September 6, 2020, at 81.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/34243631/3126224.0.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment