October 12, 1913, 100 years ago: Following the World Series, which his New York Giants lost to the A's, John McGraw hosts a reunion for Hughie Jennings and the old NL version of the Baltimore Orioles, 20 years after their 1st Pennant. (Okay, 19 years: 1894.)

After a night of heavy drinking‚ McGraw blames his longtime friend‚ business partner and teammate Wilbert Robinson, perhaps baseball's 1st great pitching coach, for too many coaching mistakes in the 1913 Series. "Uncle Robbie" replies that McGraw made more mistakes than anybody. McGraw fires him. Eyewitnesses say Robbie doused McGraw with a glass of beer and left.

Six days later, Robbie will begin a legendary 18 years as manager of the crosstown Brooklyn franchise‚ replacing Bill Dahlen. The team will carry the nickname Robins‚ as well as Dodgers‚ during his tenure.

Robbie and Mac won't speak to each other for 17 years, and after winning 3 straight Pennants together, McGraw will win just 1 Pennant in the next 7 years, while Robbie will win 2 -- the only Pennants the Brooklyn team will win between 1900 and 1941.

This is not the beginning of the rivalry between the Giants and the Dodgers, not by a long shot. That rivalry had its beginning in rivalries between clubs of New York (Manhattan) and Brooklyn when they were separate cities prior to 1898, even going back to the days of amateur baseball in the 1850s and '60s. And the rivalry between Manhattan and Brooklyn would have happened even if baseball had never been invented.

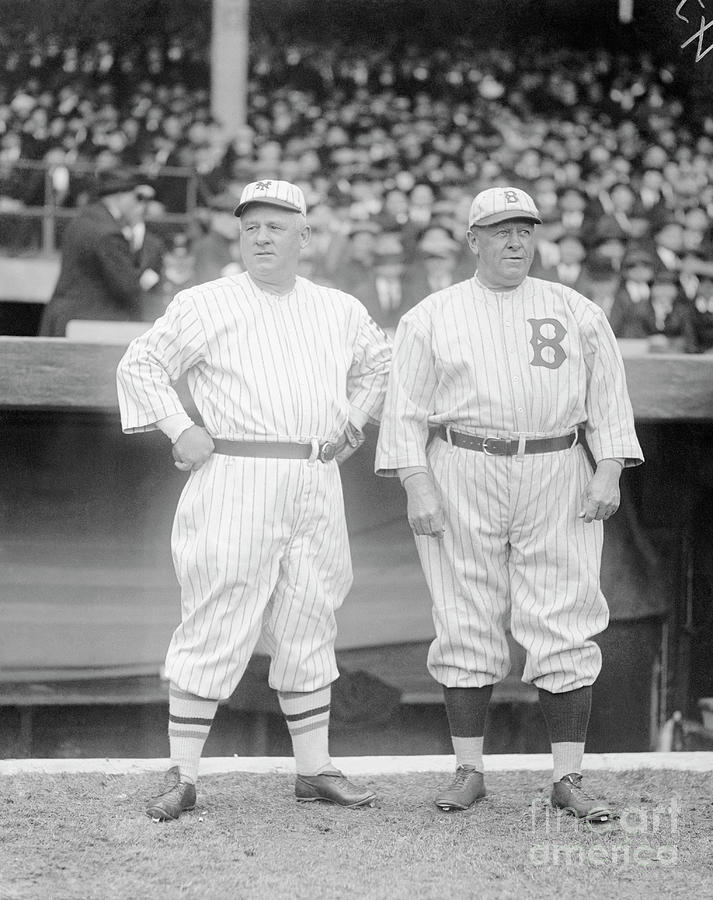

But the McGraw-Robinson bustup is the beginning of a rivalry that ruined one of baseball's great friendships, not resolved until both men were retired and near death, as seen in the photo above. Still, they both ended up in the Hall of Fame – neither lived to see the Hall's establishment, though – and are buried in the same Baltimore cemetery.

Somebody should write a book about it: We've seen books about the Giants, about the Dodgers, about the Dodger-Giant rivalry, about McGraw, and even about the old Orioles -- but the McGraw-Robinson relationship is a fascinating one. They're like the John Adams and Thomas Jefferson of baseball: Great friends in a great cause, then a nasty split and a nastier rivalry, and ultimately the relationship was repaired and the great friendship restored toward the end.

*

October 12, 1492: Christoffa Corombo – as he was known in his native Genoa, or Christophorus Columbus as he was known in Latin, or Cristobal Colon as his patron, Queen Isabella I of Spain, calls him – finally gets his ships to land. He believes he has reached South Asia. He names the island on which he lands San Salvador, after Jesus. Eventually, the island will be taken over by the English, and renamed Watling Island. Today, it is a part of the Bahamas.

Eventually, the man the English-speaking world knows as Christopher Columbus will make 4 voyages west, never fully realizing he was in what became known as “the New World,” always thinking he was in Asia. But he does start the wave of European exploration that will make the Americas – eventually named for rival Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci – possible.

Yet, considering previous voyages of the Vikings (and, some believe, the Chinese), it is disingenuous to say, “Columbus discovered America.” In fact, he never set foot on the soil of the continental U.S., coming the closest when he reached Puerto Rico. As far as I can tell, it was Juan Ponce de Leon, who came with Columbus on his second voyage in 1493, who was the first European to set foot on present-day U.S. soil, reaching Florida in 1513. (Vespucci did reach land in what’s now called South America, but not North America; the Vikings reached present-day Canada, but not present-day America.)

It’s also not true that Columbus “proved the world is round.” By 1492, most people already believed that. Even so, it would be 1522, and the conclusion of the Ferdinand Magellan expedition, before anyone sailed all the way around the world, and proved through firsthand experience that the world was round.

What does this have to do with baseball? Today, there is a Triple-A minor league baseball team in Columbus, Ohio, and a Double-A team in Columbus, Georgia. And a major league team in Washington, District of Columbia. And, of course, there is a tremendous amount of talent in lands that Columbus revealed to the Old World, including the places now known as Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.

*

October 12, 1899: The American League is founded by Byron Bancroft "Ban" Johnson, a Cincinnati sportswriter.

October 12, 1906: Joseph Edward Cronin is born in San Francisco. Both shortstop and manager for the Washington Senators, he led them to the 1933 American League Pennant, still the last Pennant ever won by a Washington baseball team (unless you count the Homestead Grays of the Negro Leagues, and even then they split their “home” games between Washington and Pittsburgh).

Senators owner Clark Griffith, himself a former pitcher good enough to make the Hall of Fame even if he hadn’t been a pioneering team owner, liked Cronin so much he let him marry his daughter Mildred. But when Boston Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey offered the perennially broke Griffith big bucks for Cronin, he sold his son-in-law, his shortstop, and his manager off all in one fell swoop.

Yawkey made Cronin his shortstop and manager, but ego made Cronin the manager keep Cronin the player at shortstop long after his skills had deteriorated. This caused the Red Sox to trade away the star shortstop of their Louisville farm team, Harold “Pee Wee” Reese.

True, this allowed Johnny Pesky to become an All-Star shortstop once Cronin finally accepted that he didn’t have it anymore, but it also led the greatest of all Red Sox, Ted Williams, to say that if the Sox had Phil Rizzuto at short, they would have won “all those Pennants” instead of the Yankees.

Finally, in 1946 – a year after he finally retired as a player, coincidence? – Cronin led the Red Sox to the Pennant, but lost the World Series to the St. Louis Cardinals, a loss often blamed on… drumroll please… shortstop Pesky “holding the ball.” Cronin only lasted another year as manager, then was “promoted” to team president. He left the team presidency in 1959 when he was offered the presidency of the American League, a post he held until 1973.

That the Red Sox became the last team to integrate is often blamed on owner Yawkey and his drinking buddy, 1950s manager Michael “Pinky” Higgins, who famously declared that there would never be a (racial slur beginning with N) on the team as long as he was the manager. And, once Yawkey fired him, the Sox then integrated. However, Yawkey hired him back, and at that point, Higgins managed more black players than his fired successor, Rudy York, or the man hired to replace York, Bucky Harris. Could it be that the real Yawkey drinking buddy/roadblock to integration was Cronin? After all, the year that the Sox integrated, with Elijah “Pumpsie” Green, was 1959, the very year Cronin left to become AL President.

Joe Cronin is a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame, and his Number 4 has been retired by the Red Sox. But if he hadn’t managed the Sox to that ’46 Pennant, I wonder if he would have deserved these honors. After all, he wasn’t a great shortstop as long as his contemporaries Rizzuto, Reese, Luke Appling, Lou Boudreau or Marty Marion were. And, as far as I can tell, he was the first manager ever to walk out to the mound and tell his pitcher, “Don’t give him anything good to hit – but don’t walk him.”

*

October 12, 1907: At Detroit’s Bennett Park, right-hander Mordecai “Three-Finger” Brown throws a 2-0 shutout, beating the Tigers to capture the World Championship for the Cubs. Although Game 1 ended in a 3-3, 12-inning tie, Chicago becomes the first club to sweep a Fall Classic.

October 12, 1910: With the AL’s season ending a week earlier than the NL’s‚ the champion Philadelphia Athletics tune up with a 5-game series against an AL all-star team‚ which includes Ty Cobb of the Detroit Tigers‚ Tris Speaker of the Red Sox‚ Doc White and Ed Walsh of the Chicago White Sox‚ and Walter Johnson of the Senators.

The A’s drop 4 out of 5 to the all-stars‚ but manager/part-owner Connie Mack will later state‚ “Those games‚ more than anything else‚ put the Athletics in a condition to outclass the National League champions.” These are not baseball’s first “all-star games,” but they were very consequential as far as determining the World Champions of baseball.

Also on this day, Robert Leo Sheppard is born in Richmond Hill, Queens, the same neighborhood that would produce Rizzuto. He played quarterback for St. John’s University in Queens, and later taught public speaking there.

In between, he taught public speaking at John Adams High School in the Ozone Park section of Queens. This means he could, arguably, have had, as one of his students, my Grandma. (Sadly, family concerns forced her to drop out, so she never did graduate. And I didn’t find out about the possibility until after both of them had died, so I could ask either if Grandma had been taught by Sheppard.)

When the NFL had a team called the Brooklyn Dodgers, speech professor Sheppard did the public-address announcements for their games. Football Dodgers owner, and Yankees co-owner, Dan Topping heard this, and asked Sheppard to do the Yankees’ games. He accepted, and from 1951 until 2007, he hardly ever missed a game. Ill health forced him to miss the 2008 and 2009 seasons, but… 57 years! On top of that, from 1956 to 2005, 50 years, he did the football Giants’ games.

Sheppard was a generous gentleman and a complete professional, from sounding like an announcer, not a shameless shill (unlike such braying animals as Bob Casey of the Minnesota Twins, may he rest in peace, and Ray Clay of the Chicago Bulls); to accepting with humility the appellation that Reggie Jackson gave him: “The Voice of God.”

Such was the appeal of Sheppard, and such is the pull of Derek Jeter, that Jeter asked that a recording of Sheppard introduce him before every at-bat, for the rest of his career, even after Sheppard died, which happened in 2010, just short of his 100th birthday. (A recording of Sheppard was also used, a few weeks ago, to introduce Mariano Rivera when he came out for his final big-league appearance.)

*

October 12, 1916: The Red Sox defeat the Dodgers/Robins, 4-1, and win the World Series by the same margin. After winning back-to-back World Series – still the only manager in the history of Boston baseball to do so – Bill Carrigan announces his retirement. He will return to the post in 1927, but, without future Hall-of-Famers such as Speaker, Harry Hooper and, uh, Babe Ruth, he will finish at the bottom of the American League instead of the top.

October 12, 1920: The Cleveland Indians win their first World Series, in Game 7 of the best-5-out-of-9 Series, 3-0 over Uncle Robbie’s Dodgers/Robins, as Stan Coveleski outduels fellow future Hall-of-Famer Burleigh Grimes for his 3rd win of the Series. It will be 21 years before the Dodgers get back into the Series; for the Indians, 28 years.

October 12, 1929: Game 4 of the 1929 World Series, at Shibe Park in Philadelphia, remains one of the wildest in postseason history. Having started a seemingly washed-up Howard Ehmke in Game 1 and having it work, Connie Mack starts 45-year-old Jack Quinn.

This seems to work, too, until the 6th, when the Chicago Cubs start scoring. By the time they stop, they lead, 7-0. Cub manager Joe McCarthy starts Charlie Root, who would later become a victim of McCarthy’s Yankees, including Babe Ruth’s “called shot,” though this quirk of history/legend does not do Root justice, as he was a fine pitcher for many years. Root enters the bottom of the 7th with an 8-0 lead.

Then the A’s come storming back. Hack Wilson, a great slugger but not the best of outfielders even when not drunk or hungover, misjudges a fly ball from Mule Haas, and it turns into a 3-run inside-the-park home run, making the score 8-7 Cubs. One of the runners scoring on the play is Al Simmons, and the great slugger storms into the dugout, yelling, “We’re back in the game, boys!” and his momentum causes him to crash into Mack – already 67 years old, if not the elderly figure most of us imagine him to have always been. Simmons apologizes profusely, but Mack, a former big-league catcher and familiar with ballplayers crashing into him, is just as enthused and tells him, “That’s all right, Al.”

The A’s score a Series record 10 runs in the inning, and ace Lefty Grove comes in to relieve and finish the Cubs off, as 10-8 remains the final score. The A’s close down the shellshocked Cubs the next day.

*

October 12, 1938, 75 years ago: Leo Durocher, already the Brooklyn Dodgers’ shortstop, is named their manager. He will hold the post for nearly 10 years, nearly all of them controversial.

He had previously been a virtual coach on the field for Frankie Frisch on the St. Louis Cardinals when they won their “Gashouse Gang” World Series in 1934. However, unlike Joe Cronin in Boston, Durocher would recognize that his shortstop skills were fading, and allow Pee Wee Reese, whom the Dodgers had purchased from the Red Sox, to succeed him in the field and in the lineup.

October 12, 1944: Frank Sinatra appears at the Paramount Theater in New York’s Times Square. About 25,000 others, mostly teenage girls – “bobbysoxers” in the lingo of the day – were turned away, and vented their frustrations by smashing store windows.

It becomes known as the Columbus Day Riot, and for those Sinatra fans who grew up to have kids screaming over Elvis Presley and/or the Beatles, complaining that they never acted that way over a musical act they liked, well, guess what, old-timers, you did.

Just as One Direction ain’t no Beatles, and Justin Timberlake ain’t no Elvis, singers from Bobby Darin to Harry Connick Jr. to Sean Combs have deluded themselves, but none of them is in Sinatra’s league. The man has more charisma dead than any of them do alive.

What does this have to do with sports? Well, by itself, nothing. But Sinatra was a big sports fan. He sang “There Used to Be a Ballpark” about Ebbets Field, although he remained a Dodger fan after they moved to L.A. He was a great boxing fan who talked Life magazine into making him their official photographer for the 1971 “Super Fight” between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier – and, I have to say, he knew what he was doing: He took good pictures. And on a Pittsburgh Steeler roadtrip to San Diego, the Steeler fan club known as “Franco’s Italian Army” (named after the half-black, half-Italian running back Franco Harris) invited Sinatra, then living in nearby Palm Springs, and offered to make him an “Honorary General” in the Army. Although he had no connection to Pittsburgh, he posed for pictures with them and accepted a helmet with generals’ stars on it.

*

October 12, 1948: The Yankees hire Charles Dillon “Casey” Stengel as their manager. Stengel had just managed the Oakland Oaks – including former star big-league catcher Ernie Lombardi and a 20-year-old sparkplug local boy from West Berkeley named Billy Martin – to the Pacific Coast League Pennant, so chances were that some big-league team would have snapped him up if the Yankees didn’t.

But his two previous big-league managing jobs, with the Dodgers (managing them in between Uncle Robbie and Leo the Lip) and the Boston Braves, were terrible. In Brooklyn in 1935, it was quipped that overconfidence might cost the Dodgers 6th place. In Boston in 1943, Casey was slightly injured when hit by a cab, and one sportswriter called the driver the man who had done the most for Boston baseball that season.

He was 58 years old in 1948, and, like Connie Mack, he always looked even older than he was. And he had a reputation as a “clown,” for such antics as tipping his cap and letting a bird fly out from under it, and protesting the weather to an umpire by walking out of the dugout with an umbrella. This was not a man who would manage “the Yankee way,” sportswriters said.

Then again, Casey really didn’t have the players in Flatbush or in Allston. Once he proved everyone wrong by winning the 1949 Pennant, he said, with a mixture of pride and humility, “I couldn’t have done it without my players.” Finally having the horses, Casey went on to manage the Yankees for 12 years, winning 10 Pennants and 7 World Series. He then managed the Mets in their first 4 years, 1962-65.

He is still the most successful manager in baseball history. He was fast-tracked to election to the Hall of Fame after his retirement, the Yankees dedicated a Plaque in Monument Park to his memory, and he lived to see both the Yankees and the Mets retire his Number 37.

*

October 12, 1954: The AL owners approve the shift of the Philadelphia Athletics franchise to Kansas City. Roy and Earle Mack, sons of the now-senile Connie Mack, sell the A’s to Arnold Johnson, a Chicago-based trucking magnate, 25 years to the day after the team’s magnificent 10-run inning in the ’29 World Series.

Johnson’s bid is $3‚375‚000 for the team and stadium‚ Shibe Park, recently renamed Connie Mack Stadium. He says he will sell the stadium to the Phillies for $1‚675‚000, although Phils owner Bob Carpenter, a very wealthy man as a member of both the Carpenter and the duPont families, says, “I need Shibe Park like I need a hole in the head.”

One of the offers for the team is from a wealthy Texas group that proposes to move the A’s to Los Angeles, but Kansas City, long a hotbed of minor league and Negro League baseball, gets major league status for the first time since the Kansas City Packers of the Federal League in 1915 – or, if you don’t count that, since the Kansas City Cowboys of the old American Association in 1889.

*

October 12, 1955: The St. Louis Cardinals fire manager Harry “the Hat” Walker, and replace him with former big-league pitcher Fred Hutchinson. Walker, like his brother Fred “Dixie” Walker, a former Dodgers slugger, was a really good hitter in his day, but he was not such a good manager. (He would, however, return to the Cards as a coach, and later manage the Pittsburgh Pirates, and would also take the Houston Astros to their first Pennant race in 1969.) But his day as a player was done.

He had used himself as a pinch-hitter in the ’55 season, but his firing means that, for the first time in the history of baseball, there are no current player-managers.

Frank Robinson (’75 & ’76 Indians), Joe Torre (’77 Mets), Don Kessinger (’79 White Sox) and Pete Rose (’85 and ’86 Reds) would briefly be player-managers, before Robinson, Torre and Rose retired as players and Kessinger was fired (and subsequently retired as a player). But, from this point forward, player-managers would be frowned upon. The last player-manager to get his team into a Pennant race was Lou Boudreau with the ’51 Red Sox. The last to win a Pennant, much less a World Series, was Boudreau with the ’48 Indians.

*

October 12, 1958: For the first time since the Giants moved to San Francisco, Willie Mays plays baseball in New York City.

At Yankee Stadium, 3 days after the conclusion of the World Series, the Say Hey Kid leads a team of National League All-Stars that also includes former Brooklyn Dodgers Gil Hodges and Johnny Podres, plus future Hall-of-Famers Ernie Banks, Frank Robinson, Richie Ashburn and Bill Mazeroski -- but not, oddly, Hank Aaron. I guess Hank, just beaten by the Yankees in Milwaukee, didn't want to go back to Yankee Stadium so soon.

They play a team of American League All-Stars captained by Mickey Mantle, including his Yankee teammates Whitey Ford and Elston Howard, and former teammate Billy Martin, plus Hall-of-Famer Nellie Fox and All-Stars Rocky Colavito (a Bronx native) and Harvey Kuenn. All of them, including Mays and Mantle, had Frank Scott as their agent.

The game was not broadcast, on either television or radio, and 21,129 fans came out -- which doesn't sound like much, especially in the first year with the Dodgers and Giants gone, but it was more than any of them averaged the year before, the last year with all 3 of them in New York. And most of them were cheering for the NL team -- whether it was because they missed the Giants and Dodgers in general, or Willie in particular, or whether Yankee fans couldn't be bothered to show up for a game that didn't count for anything but filling the players' pockets, I don't know. (And that was the reason the game was played: Both Mantle and Mays were having money problems at the time.)

The NL team won, 6-2. Mays went 4-for-5. Mantle went 1-for-2 before taking himself out.

*

October 12, 1965: Following the departure of the Braves for Atlanta, a Milwaukee-based used-car salesman founds Milwaukee Brewers Baseball Club, Inc., named for the former minor-league team from the city, in the hopes of attracting an expansion team or buying an existing team and moving it to the Beer City.

The salesman’s name is Allan Huber Selig Jr. Yes, Bud Selig. He bought the Seattle Pilots on the eve of the 1970 season, moved them, and renamed them the Milwaukee Brewers, and has been Commissioner of Baseball since 1992. This, after starting out as a used-car salesman. He had become rich and famous by selling cars to the Braves players, including selling rookie catcher Joe Torre his first car.

*

October 12, 1967: Baseball and the Summer of Love converge on Fenway Park in Boston for Game 7 of the World Series, as a fan holds up a sign saying, “THE RED SOX ARE VERY BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE.”

But the prediction made the day before, after a Game 6 win, by Sox manager Dick Williams, of “Lonborg and champagne,” does not happen: On only 2 days’ rest, Gentleman Jim has nothing, and gets shelled. Even opposing pitcher Bob Gibson, himself on only 3 days rest (and having won Game 7 in ’64 on just two) hits a home run off him. The Cardinals win, 7-2, for Gibson’s 3rd win of the Series, the team’s 2nd title in 4 seasons, and their 7th World Championship.

For the Red Sox, “the Impossible Dream” came to an end one game too soon, but the season did revitalize the franchise, restoring its profitability and its place of veneration among the people of New England. They lost the World Series, but they cannot be called a failure. Without this season, the Red Sox might have ended up leaving Fenway Park, sharing a stadium out in Foxboro with the NFL’s Patriots. Or owner Tom Yawkey, who really wanted out of Fenway, might have moved them out of Boston entirely.

So, even more than 2004, this is the most important season in Red Sox history. Years later, after the Red Sox failures of 1975, ’78 and ’86, but before the tainted triumphs of 2004 and ’07, Boston Globe columnist Dan Shaughnessy would write that, of all Red Sox teams, this one is absolved from criticism by “Red Sox Nation” – which, he says, essentially began that summer.

By the same – pardon my choice of words here – token, this was an incredibly important season in St. Louis. The holdovers from the 1964 season proved it was no fluke, and, much more so than the ’64 team, the ’67 team, with its mixture of white stars (Tim McCarver, Dal Maxvill and an aging but still power-hitting Roger Maris), black stars (Gibson, Lou Brock and Curt Flood) and Hispanic stars (Orlando Cepeda and Julian Javier) showed St. Louis, still thinking of itself as a Southern city, what integration could really do. Fans in Brooklyn had learned that 20 years earlier.

Yet, somehow, the 1964-68 Cards, as good as they were, have not been celebrated by Baby Boomers as much as have the 1950s and ’60s Yankees, the 1950s Dodgers, the ’60 and ’71 Pirates, the 1962-66 Dodgers, the 1962-66 Giants, the 1966-71 Orioles, the ’67 Red Sox, the ’68 Tigers and the ’69 Mets. Hopefully, that’s mainly because St. Louis was, and is, one of baseball’s smallest markets. Still, the Cardinals were then, and are now, one of baseball’s most profitable and most admired franchises.

*

October 12, 1969: The Mets win a World Series game for the first time, taking Game 2 at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore. Al Weis’ 9th-inning single breaks up a pitchers’ duel between the Mets’ Jerry Koosman (who is relieved in the bottom of the 9th by Ron Taylor) and the Orioles’ Dave McNally.

The film Frequency tells the fictional tale of an atmospheric phenomenon that allows a 1999 NYPD detective and Met fan, played by Jim Caviezel, to use his father’s old ham-radio set to talk to his father, a 1969 fireman, played by Dennis Quaid. October 12, 1969 was the day the father died in a fire, when the son was just 6, and the son is able to warn him from the future. The result is that the father, and the teenage girl he would have failed to rescue from the fire, get out alive.

But interfering with time means that, because she wasn’t preparing for her husband’s funeral, the cop’s mother, a nurse, saves the life of a serial killer who would otherwise have died, and several more women end up dying – including the mother herself, played by Elizabeth Mitchell (who, unlike Quaid, is actually younger than Caviezel).

Now, instead of having his mother but not his father from 1969 to 1999, he now has his father but not his mother from 1969 to 1989 – the father living long enough to see the son graduate from the police academy, but dying from smoking before the son makes Detective.

Using the ham radio, father and son, roughly the same age as each other, track down the killer, played by Shaun Doyle, a Canadian actor who appeared on the series Lost and Big Love, and now appears on the SyFy series Lost Girl. He was so creepy in Frequency that he really should have played the Joker in The Dark Knight, and not just to save Heath Ledger’s life. Seriously, look at his face and his hair (in the 1969 sequence) at the end of the film, and tell me he wouldn’t have made a good Joker.

The kicker is that, as a result of his 1969 confrontation with the killer, the father begins to be suspected for the killings (which do not yet include his wife) by a young cop, played by Andre Braugher, who will be the son’s mentor and boss in 1999.

The way the father gets out of this, and back on the killer’s trail, is that Game 5 of the Series is being shown on a TV behind them. Having been told what’s going to happen by his son from 30 years in the future, he tells the cop (whose nickname is Satch, after baseball legend Satchel Paige) about the Cleon Jones shoe-polish incident and the subsequent Donn Clendenon home run. When it happens, the cop realized the father really is telling the truth about these messages from his son from the future, releases him, and… well, you’ll just have to see the movie. It’s a fantastic thriller, and I highly recommend it – even though the Mets are glorified in it.

Also on this day, with a connection to the Mets, Jose Valentin is born in Manati, Puerto Rico. The infielder last played in the majors for the Mets in 2007, and his only trip to the postseason was with the AL Central Champion White Sox in 2000. He now manages the Fort Wayne Tin Caps in the Class A Midwest League.

*

October 12, 1970: Tanyon James Sturtze is born. Not a Yankee pitcher I care to say anything else about. He was born in Worcester, Massachusetts — a “Manchurian Candidate” for the nearby Red Sox?

Charlie Ward is also born on this day, in Thomasville, Georgia. The 1993 Heisman Trophy winner led Florida State to that season’s National Championship, but no NFL team would draft him, so he played for the NBA’s Knicks, not for the Giants or the Jets. Which is too bad, because, for a time, when the Giants had Dave Brown and Kent Graham, and the Jets had Neil O’Donnell and Bubby Brister, Ward was the best quarterback in New York. He did, however, play in the 1999 NBA Finals for the Knicks. He is now head coach of the football team at a private Christian high school in Houston.

Kirk Cameron is also born on this day, in Los Angeles. He has spent most his time since Growing Pains went off the air making Christian Fundamentalist-themed films, including the movie versions of the Left Behind fables. His sister Candace Cameron, one of the stars of Full House, married hockey star Valeri Bure (who also has a famous brother, hockey legend Pavel Bure).

October 12, 1972: The Oakland Athletics defeat the Detroit Tigers, 2-1, and take the American League Pennant. The winning run is scored by Reggie Jackson on the front end of a double-steal, but Reggie tears his hamstring, and is unable to play in the World Series. He will make up for that many times, as he is the only man to win World Series MVPs with two different teams, the A’s in ’73 and the Yankees in ’77.

October 12, 1977: The Dodgers pounce on aching Yankee starter Catfish Hunter, and win Game 2, 6-1, and tie up the Series. Billy Martin is criticized for putting Catfish on the mound when he’d been injured and hadn’t pitched in a month, but it allowed Billy to start Mike Torrez in Game 3, rookie sensation Ron Guidry in Game 4, and Don Gullett in Game 5, all on full rest.

During the ABC broadcast, the camera on the Goodyear blimp caught the image of an abandoned school on fire, just a few blocks east of Yankee Stadium. “There it is, ladies and gentlemen,” said ABC’s Howard Cosell. “The Bronx is burning.” This became the title of Jonathan Mahler’s book about life in New York City in 1977, and of the ESPN miniseries about it.

October 12, 1980: The Phillies win the Pennant with a 10-inning 8-7 win over the Astros in the deciding Game 5 at the Astrodome. Each of the last 4 games of this epic series was decided in extra innings. The Phils‚ down by 3 runs to Nolan Ryan in the 8th‚ rally to tie, and center fielder Garry Maddox makes up for his Playoff goof of 2 years earlier by doubling home the winning run and catching the final out.

Although Tug McGraw had been on the mound when the Phils clinched the Division in Montreal, and would be on the mound when they clinched the World Series at home 9 days later, he was already out of the Pennant-clincher before it ended. Dick Ruthven, the Phils’ Number 2 starter behind Steve Carlton, turned out to be the pitcher on the mound at the end. This was the Phils’ first Pennant in 30 years, and only the second by a Philadelphia team in 49.

October 12, 1982: The Milwaukee Brewers win the first World Series game the franchise has ever played, clobbering the Cardinals, 10-0 at Busch Memorial Stadium. Paul Molitor sets a Series record, becoming the first player to collect 5 hits in a game. Robin Yount gets 4 hits.

October 12, 1986: Game 5 of the ALCS. One loss away from elimination and trailing 5-2 entering the 9th‚ the Red Sox stage one of the most improbable comebacks in post-season history, winning 7-6 over the Angels in 11 innings.

After Don Baylor’s 9th-inning home run reduces the deficit to 5-4‚ reserve outfielder Dave Henderson slugs a 2-out‚ 2-run home run off Donnie Moore to give Boston a 6-5 lead. California ties the score with a run in the bottom of the 9th but Henderson‚ who had appeared to be the goat when he dropped Bobby Grich’s long fly ball over the fence for a home run in the 7th inning‚ delivers a sacrifice fly in the 11th for the winning run.

The Sox would win the Pennant 3 days later. Three years later, still despondent over having given up the home run that blew the Pennant for the Angels, Moore shot his wife, then himself. She lived, he didn’t. A loss in a baseball game may be a terrible disappointment, but there is a difference between disappointment, however great, and tragedy.

Henderson would also hit the home run that appeared to give the Sox Game 6 of the World Series, and their first title in 68 years. That they did not finish the job, and how they failed, has become legend. If they had, Henderson would have become a god in New England. That he is not is no fault of his.

He would later help Oakland with 3 straight Pennants, and he was invited to throw out the ceremonial first ball before Game 3 of the 2009 ALDS between the Red Sox and Angels. Unfortunately for the Sox, it didn’t work any more than the Yankees bringing out Bucky Dent to do the honors before Game 7 of the 2004 ALCS between the Yanks and the Sox.

October 12, 1987: The Minnesota Twins defeat the Detroit Tigers, 9-5, and win their first Pennant in 22 years. This was a major upset, as the Twins had won just 85 games in the regular season, and many people (including myself) were picking the Tigers to win it all. We did not reckon with the power of the Metrodome. Fortunately, the only people who will have to do so now are people whose favorite NFL team goes in there to play the Vikings.

This is the first Pennant ever won by a team playing its home games indoors — the Twins’ 1965 Pennant was won while they still played outdoors, in the suburb of Bloomington, at Metropolitan Stadium.

October 12, 1988, 25 years ago: Orel Hershiser shuts out the Mets, and the Dodgers win Game 7 and the Pennant, 6-0. New York – the National League “half” of it, anyway, the half that should have cared about this – finally had a chance to stick it to the evil O’Malley family, and they blew it. The Mets, whose fans did not realize that their “dynasty” had ended without really becoming one, would not return to the NLCS for 11 years – but that’s sooner than did the Dodgers, who waited 20 years.

October 12, 2003, 10 years ago: Joan Kroc, former owner of the San Diego Padres (inheriting them from her husband, McDonald’s tycoon Ray Kroc) dies at age 85. She had recently been the formerly “anonymous angel” who donated a huge sum to disaster relief when floods hit the Upper Midwest.

On this same day, the best possible thing that could happen in the Yanks-Red Sox ALCS does happen: Rain. An extra 24 hours gives everyone a chance to cool off a little.

*

October 12, 2005: In Boston, it’s Larry Barnett (1975 World Series Game 3). In St. Louis, it’s Don Denkinger (1985 World Series Game 6). In Baltimore, it’s Rich Garcia (1996 ALCS Game 1). In Atlanta, it’s Eric Gregg (1997 NLCS Game 5). In Orange County, California, the most hated of all umpires is Doug Eddings.

Game 2 of the ALCS at U.S. Cellular Field in Chicago. The Angels are up 1 game to 0 in the ALCS. Game 2 is tied 1-1 with the White Sox batting in the bottom of the 9th and 2 out. White Sox catcher A. J. Pierzynski faces Angels relief pitcher Kelvim Escobar, who quickly gets 2 strikes. Pierzynski swings at Escobar’s third pitch, a split-fingered fastball that comes in very low. Angels catcher Josh Paul says after the game, “I caught the ball, so I thought the inning was over.”

Eddings later said the ball had not been legally caught, but he made no audible call that the ball hit the ground. Pierzynski, already having had a reputation as a rough player, takes a couple of steps toward the dugout, but then, noticing that he had not heard himself called out, turns and runs to first base while most of the Angels are walking off the field. He makes it to first base safely. A pinch-runner, Pablo Ozuna, replaces Pierzynski and steals second base, and scores on a base hit by third baseman Joe Crede for the winning run.

The controversy surrounding the play concerns both whether Eddings’ ruling that the ball hit the ground was correct, and the unclear mechanic for signaling the ruling. Eddings did not indicate no-catch signals during the game. In fact, in the 2nd inning of the same game, Eddings had ruled no catch on a 3rd strike to Garret Anderson of the Angels, but the White Sox were not aware of the ruling until Eddings called Anderson out as he entered the dugout. At the time, professional umpiring mechanics did not dictate a specific no-catch signal or a “no catch” verbalization after an uncaught third strike. A mechanic has subsequently been added.

After the game, Eddings explained his actions: “My interpretation is that was my ‘strike three’ mechanic, when it’s a swinging strike. If you watch, that’s what I do the whole entire game. … I did not say ‘No catch.’ If you watch the play, you do watch me — as I’m making the mechanic, I’m watching Josh Paul, and so I’m seeing what he’s going to do. I’m looking directly at him while I’m watching Josh Paul. That’s when Pierzynski ran to first base.”

Angels fans remain convinced that Eddings screwed them over and cost them a Pennant – and, since the ChiSox went on to sweep the Houston Astros in 4 straight, that Eddings also cost them the World Series. They are wrong: The video clearly shows the ball touching the ground, and Angels catcher Benjie Molina should have tried to throw Pierzynski out at first. He didn’t, therefore Pierzynski was entitled to the base. Eddings was right, and Pierzynski acted within the rules of the game.

And here’s the key: The series was still tied. While the next 3 games were going to be in Chicago, theoretically the Angels still had as much chance to win the Pennant as the Pale Hose did. They could have shut their traps, gotten their acts together, and gone out and won Game 3 in Chicago, taken a 2-1 lead in the series, and it would have been a very different story. Instead, like the ’85 Cards on the Denkinger/Jorge Orta play, and like the ’78 Dodgers on the Reggie Jackson “hip-check” play, they let the incident get into their heads. They lost 3 straight and the Pennant. They did not deserve to win that one. The White Sox, thinking clearly, did.

October 12, 2010: Behind the complete-game effort by Cliff Lee, the Texas Rangers beat Tampa Bay, 5-1, in the decisive Game 5 of the ALDS at Tropicana Field, for the 1st Playoff series victory in franchise history. They are the last major league club to accomplish the task — unless you count the fact that the Montreal Expos, who did it in the strike-forced split-season format of 1981, still haven’t done it since they became the Washington Nationals in 2005.

The Rangers, who will take on the Yankees for the AL flag, lost their three previous playoff appearances with first-round losses to the Bronx Bombers in 1996 and 1998-99.

October 12, 2012: The biggest game in Washington baseball in 79 years is Game 5 of the NLDS at Nationals Park. The Nationals lead the Cardinals, 7-5 going into the 9th inning.

But Nats reliever Drew Storen implodes, allowing a double to Carlos Beltran, a walk to Yadier Molina, another walk to David Freese, a single to Daniel Descalso, a stolen base by Descalso, and a single to Pete Kozma. The Nats go down 1-2-3 in the bottom of the 9th, and the Cards win, 9-7, and advance to the NLCS. The Nats went from having, according to Baseball-Reference.com, a 93 percent chance of winning the game to losing it.

Concerned about putting too much stress on his arm after coming back from Tommy John surgery at the start of the season, the Nats had shut down ace pitcher Stephen Strasburg for the season after September 7, at which point he had pitched 159 innings. I wonder what Nats management would have given to have Strasburg pitch to just 1 batter: Descalso, when there were 2 outs and the score was still 7-5. Keeping Strasburg off the postseason roster was a major blunder.

But, hey, Strasburg came back strong in 2013, didn’t he? Not really: He threw 183 innings, and had a 3.00 ERA and a 1.049 WHIP, but was only 8-9, after going 15-6 the year before.

Arsenal's next big sale is so obvious it hurts

33 minutes ago

No comments:

Post a Comment