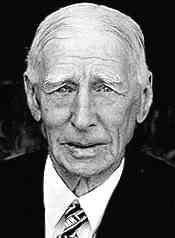

A former major league catcher, occasionally good but never great, he managed the Philadelphia Athletics from their founding in 1901 until 1950 -- 50 seasons. He won American League Pennants in 1902, 1905, 1910, 1911, 1913, 1914, 1929, 1930 and 1931. He won the World Series in 1910, 1911, 1913, 1929 and 1930.

But increase in salaries caused by the arrival of the Federal League in 1914 caused him to break up his 1st dynasty, and the stock market Crash of 1929 wiped out his savings, causing him to break up his 2nd dynasty, as he had no more income outside of the team.

He was never able to rebuild the A's as he had in the 1920s. And, also being the owner, he was not going to be fired as manager, even as he entered his 80s, and began making inexplicable moves, including calling out names of pinch-hitters, players who hadn't been on the A's in years.

Finally, after the 1950 season, his sons ganged up on him. Earle and Roy Mack, his sons from his 1st marriage, did not get along with Connie Mack Jr., his son from his 2nd marriage. The one thing they agreed on was that Connie Sr., at age 87, had to go, as field manager, as general manager, and as owner in all but name.

Their financial management was no better than his, and in 1954, they sold the A's to Arnold Johnson, who ran a Chicago-based trucking business, and he moved them to Kansas City. Mack was dead in a year and a half, a few months after that scourge of the elderly, a hip-breaking fall.

*

Mitchell Nathanson, author of The Fall of the 1977 Phillies, makes the case that, unlike with the St. Louis Browns and Cardinals, and the Boston Braves and Red Sox, in the case of Philadelphia, the wrong team moved and the wrong team stayed.

He's got a point. The AL's A's not only were more successful than the National League's Philadelphia Phillies -- from 1901 to 1949, winning 9 Pennants to the Phils' 1, in 1915 -- but were the landlords at Shibe Park, while the Phils, who'd the inadequate Baker Bowl a few blocks away, were the tenants. The Phils' stirring 1950 "Whiz Kids" Pennant changed the recent history, but not the overall history.

Here's what the teams did after the A's moved in 1954:

* The Phillies have made the Playoffs 12 times, won the NL Eastern Division 11 times, won 5 Pennants, and won the World Series in 1980 and 2008. Not a bad record, but this includes the near-misses for the postseason in 1964, 1982, 2004, 2005 and 2006; and the terrible postseason chokes of 1977 and 1978, plus losing World Series they had very good chances to win in 1983, 1993 and 2009.

* The A's did nothing in Kansas City, but since moving again, to Oakland, in 1968, they've made the Playoffs 18 times, won the AL Western Division 16 times, the Pennant 6 times (although not since 1990) and the World Series 4 times (1972, 1973, 1974 and 1989). Indeed, the A's won more World Series in 3 seasons (1972 to 1974) than the Phils have won in the competition's entire history (1903 to 2015).

* Just since the A's moved to Oakland, 1968 to 2015, they've won nearly as many Pennants, 6, as the Phils have in their entire history (1883 to 2015), 7.

So, in hindsight, Philadelphia and its fans might have been better off keeping the A's and losing the Phils.

And in the 25 years between the Crash of '29 and the A's move, not only the Phils' on-field fortunes as futzed-up as those of the A's, but so were their finances. Gerry Nugent had to get a loan from the other NL owners in 1943, just so he could send the team to spring training. He sold them to William D. Cox, who had plenty of money and was willing to spend it, but was caught betting on the Phils, and so was banned from baseball. A new owner stepped in.

So if the Phils were in that bad a shape, why did they stay, and not the A's? Did the 1950 Pennant really matter all that much?

Not really. It would be a "Best of the Rest" in a list of...

The Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame the Philadelphia Athletics for Moving to Kansas City

5. Demographics. In the 1950 Census, Philadelphia was cited as having just under 2.1 million people. This was the most it would ever have. Indeed, the population was already going down. It would be a shade over 2 million in 1960, a little under that in 1970, under 1.7 million in 1980, under 1.6 million in 1990, and bottom out at just over 1.5 million in 2000. It's now believed to be about 1,553,000.

Philadelphia, 1950. Prior to the 1980s,

they really didn't have skyscrapers.

In the foreground, that's 30th Street Station on the left,

and the main post office on the right.

Meanwhile, the suburbs boomed, so that the Philly region, a.k.a. the Delaware Valley -- Eastern Pennsylvania, South Jersey and Northern Delaware -- has about 7.1 million people, making it the nation's 7th-largest market. This suburban boom will be revisited in Reason Number 3.

A more recent photo, taken from a similar angle.

As you can see, the city has grown up. Way up.

Ahead of Philly in metropolitan population are New York (23 million), Los Angeles (18 million), Chicago (almost 10 million) and San Francisco (8.6 million), all with 2 MLB teams, although San Fran may lose the Oakland Athletics in the next few years.

Also ahead of Philly are Boston (just over 8 million) and Dallas (7.2 million). And nobody is credibly suggesting that Boston, whose Red Sox are no longer selling out every game, or Dallas, a football-first city which barely supports the Texas Rangers as it is, should get a 2nd Major League Baseball team.

When the Phillies were winning 5 straight NL East titles from 2007 to 2011, and Citizens Bank Park was full 81 times a year -- even after the economic Crash of 2008, the worst since the Crash of 1929 that wiped Connie Mack out -- there was talk that Philly might get a 2nd team, either through expansion by the AL or a moved team, playing at CBP until they could get their own ballpark built. There was even talk that, after over half a century away, the A's might "come home." But the Phils' 2012 collapse, and their subsequent nosedive in attendance, put an end to that talk, before it could reach an even remotely serious stage.

Philadelphia could support 2 major league baseball (capitalized or otherwise) teams before World War II. But not afterward. As with Boston and St. Louis, 1 of the 2 teams was going to have to go.

4. The Deaths of the Shibe Brothers. When Ben Shibe, Connie Mack's co-owner and the man for whom their ballpark was named, died in 1922, his shares of the team went to his sons. Thomas F. Shibe became team president, and John F. Shibe became vice president.

Tom Shibe, left, with Ty Cobb,

who closed his career with the A's in 1927 and '28.

Tom and Jack Shibe were "sportsmen" in the old sense, also interested in hunting and speedboat racing, respectively. Tom essentially ran the ballpark, while Mack ran the team, filling the roles of manager and what we would now call "general manager."

Tom died in 1936. Jack replaced his brother Tom as president, and Connie installed his son Roy Mack as vice president. All seemed fairly stable. But Jack got sick shortly after becoming president, dying the next year. Connie, club treasurer from day one, installed himself as president, and bought out the brothers' widows, making himself the majority owner for the first time.

Why not promote one of the next generation of Shibes? Because neither Tom nor Jack had children, while Ben's daughters (Tom's and Jack's sisters), being women, were not seriously considered for team leadership roles, even though they had stock in the club.

One of Ben's sons-in-law, Ben MacFarland, was named traveling secretary. His brother, Frank MacFarland, was named assistant treasurer. But the MacFarlands were frozen out of management decisions regarding the team or the stadium, neither of which got proper maintenance. In essence, they had titles, but no power.

Connie set Roy, Earle and Connie Jr. up to run the team after him, frequently citing "The House of Mack." (Even that wasn't correct: His full name was Cornelius Alexander McGillicuddy. He only shortened his name to "Mack" as a young player so that it would fit in a box score without being abbreviated into something like "M'Cuddy.")

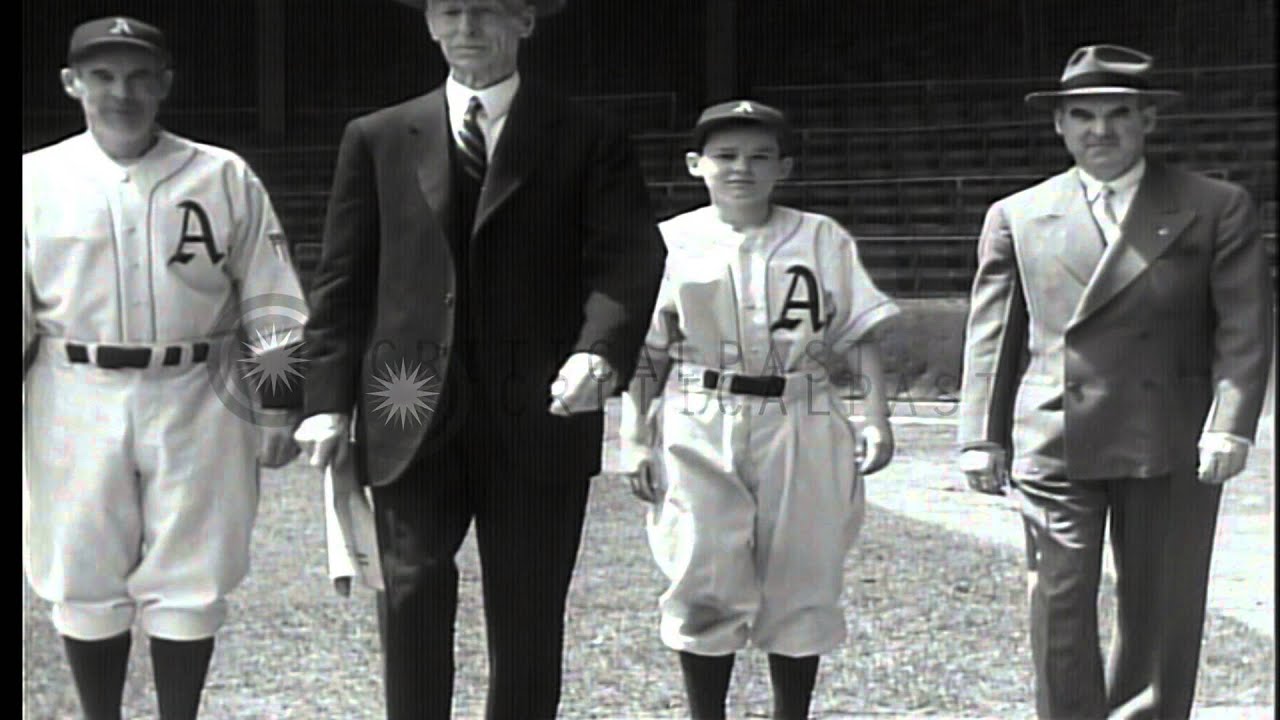

L to R: Earle Mack, Connie Mack, Connie Mack Jr., Roy Mack

(Roy Mack died in 1960, only outliving his father by 4 years. Earle lived on until 1967, and Connie Jr. until 1996. His son Connie III became a U.S. Senator from Florida, and Senator Mack's son Connie IV was elected to the House like his father, but has failed in his only Senate bid thus far.)

3. Ballparks. Part of the problem was Shibe Park itself. Opening on April 12, 1909, it was the 1st concrete and steel stadium in Major League Baseball. The Shibe brothers expanded it in 1925, and eventually seating capacity would reach... 33,608. This made it smaller than any ballpark in use in MLB today. When it finally closed on October 1, 1970, 3 months after the end for Crosley Field in Cincinnati and Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, only Fenway Park in Boston was similarly small.

And losing his money in the Crash of '29 and buying out the Shibe widows had tapped Connie Mack out. He tried adding more seats, but he couldn't afford the maintenance on Shibe Park. When his sons pushed him out, they took out a tremendous mortgage on the ballpark, and couldn't make the payments on it, so they couldn't keep the place up either.

Access was a big problem, too. Although North Philadelphia hadn't yet descended into urban blight, there was no major highway nearby. Public transportation? The trolleys had been cut back, so to get to Shibe Park, you either had to take the Broad Street Line subway to North Philadelphia, or the Pennsylvania Railroad to Germantown Junction (now SEPTA's North Philadelphia commuter rail station), or the Reading Railroad to North Broad Street Station; and then take a bus 7 blocks down Lehigh Avenue. Even if you weren't afraid of the neighborhood (and by the time the Phillies made their 1964 Pennant run, lots of people were), that was a hassle.

In contrast, the Kansas City Municipal Stadium, built in 1923, was being double-decked in the 1954-55 off-season, doubling its seating capacity to 35,020, and while its neighborhood soon deteriorated as well, it had better access roads and more parking.

When the A's were sold, the Macks sold Shibe Park to the Phillies, even though their owner Bob Carpenter said, "I need Shibe Park like I need a hole in the head."

He renamed it Connie Mack Stadium in honor of the Grand Old Man, and spent the rest of the 1950s and nearly all of the 1960s trying to get it replaced, finally convincing the city to build what became Veterans Stadium for the Phillies and the NFL's Eagles, who left Connie Mack Stadium for the University of Pennsylvania's Franklin Field in 1958, before groundsharing with the Phils again from 1970 to 2003, when each had a new stadium built adjacent to the Vet at the South Philadelphia sports complex.

2. Kansas City. It had been a very good baseball town, with the minor-league Blues (a Yankee farm team from 1936 to 1954) and the Negro Leagues' Monarchs each winning multiple Pennants. If the A's didn't move there for 1955, another major league team would have done so. If that hadn't happened by 1960, surely, they would have gotten an expansion franchise.

It worked, sort of: Although their attendance in Kansas City was never great, in each of the A's 1st 7 seasons there, they got more fans than in each of their last 5 seasons, and in 24 of their last 25 seasons, in Philadelphia. Even their worst seasonal attendance in K.C. was better than 4 of their last 5 years in Philly.

Once the A's moved to Oakland, and were replaced by the Royals, fans who had never warmed to Charlie Finley, who'd bought the A's after the death of Arnold Johnson in 1960, came out in better numbers than the A's franchise would ever see until the 1980s.

The Royals' recent success, including last year's World Series and the last 2 AL Pennants, shows that Kansas City was a sleeping giant as far as baseball markets was concerned. All they needed was to show that ownership cared. It took ownership a while to show it, but they have, and the fans are coming out.

But the A's might never have moved to Kansas City -- and the Phillies might have, or might have moved somewhere else -- if the right man hadn't stepped in to buy the Phillies.

1. The Carpenters. No, not the singing siblings of the 1970s. In November 1943, Robert Ruliph Morgan Carpenter bought the Phillies from the banned William D. Cox.

Known as Ruly, he could afford it: The Carpenters were one of the oldest and wealthiest families in Philadelphia and in neighboring Wilmington, Delaware. Ruly married into the family in Delaware, the du Ponts, giving him control of more money. He became an executive at E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company (a.k.a. simply "DuPont," although the family has never capitalized the D in their names), and made even more money.

He was a strong supporter of the University of Delaware, including its athletic department. But he didn't really want to run the Phillies. So he left that to his son, Robert Ruliph Morgan Carpenter Jr. Known as Bob Carpenter, he totally reorganized the team, giving it a real front office, a real farm system, and a real scouting department, all for the first time. The result was the 1950 Pennant, featuring Hall-of-Famers Robin Roberts and Richie Ashburn, Most Valuable Player Jim Konstanty, and Dick Sisler, whose home run on the final day of the season clinched the flag.

Bob Carpenter

Ruly Carpenter, now 75, with his copy of the Commissioner's Trophy

for winning the 1980 World Series

The Carpenter family sold the Phillies soon thereafter, and is no longer involved with the team, but retains a small ownership, and still supports University of Delaware athletics. But once they bought the Phillies, and put to work money that the Mack and Shibe/MacFarland families simply didn't have, the A's, despite the huge advantages in ownership and history with the Phillies, were doomed as far as Philadelphia was concerned.

VERDICT: Not Guilty. As many mistakes as the Macks made, there were circumstances beyond their control that put an end to the Athletics' tenure in Philadelphia.

The A's had to go. And it worked out. For a while. Why did they leave Kansas City after only 13 seasons? That's a blog post for another time.

No comments:

Post a Comment