People complained that the Cleveland Indians' Chief Wahoo

was a racist caricature. But the Braves' "Laughing Indian"

looked like a mashup of the most stereotypical features

of both Native Americans and African-Americans. It was worse.

They were successful on the field, too. In 1953, boosted by this newfound home-field advantage and a farm system that began paying off, they rose to 2nd place, winning 92 games, albeit 13 games behind the Pennant-winning Brooklyn Dodgers. In 1954, they won 89 and finished 3rd. In 1955, they finished 2nd again. In 1955, they finished 2nd again, although, again, the Dodgers won the Pennant by 13 games. In 1956, they came within 1 game of the NL Pennant, again finishing 2nd to the Dodgers.

In 1957, they won the Pennant, and won the World Series, too, beating the Yankees. In 1958, they won another Pennant, losing the Series to the Yankees in 7 games. In 1959, they tied the now-Los Angeles Dodgers for the Pennant, losing a Playoff. In 1960, they finished 2nd. In 1964, they finished 5th, but only 5 games out of 1st place.

They had a winning record every year they were in Milwaukee -- 13 straight years, as many winning records as they had in their last 50 seasons in Boston. They seemed to be the very model of a successful baseball franchise, both on the field and at the box office.

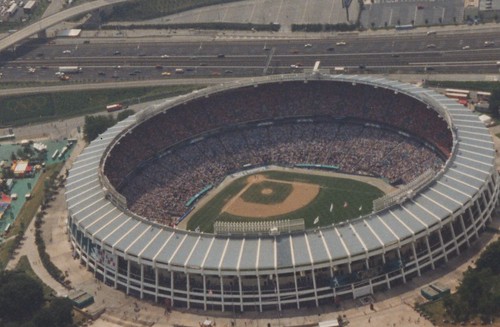

Milwaukee County Stadium during the 1957 World Series

After the 1965 season, they moved to Atlanta. What happened?

The Braves leaving Boston made sense. Moving to Milwaukee made sense. But leaving Milwaukee didn't seem to make sense. And moving to Atlanta seemed to make no sense, either: While they topped 17,000 in per-game attendance in 3 of their 1st 4 seasons in Atlanta, they didn't do so again until 1982. That year, 1983 and 1984 were the only 3 of their 1st 25 seasons in Atlanta that topped the 20,000 mark, which they beat in 7 of their 13 Milwaukee seasons. While the South liked baseball, did then and does now, football was the big game there, always has been, and always will be.

And remember: At the time, the Braves weren't sharing Milwaukee. There was no NBA team in town after the Hawks moved to St. Louis in 1955, and the expansion Bucks wouldn't arrive until 1968. There has never been an NHL (or even a WHA) team in Milwaukee. The Green Bay Packers were 117 miles away. That's a 2-hour drive. When it came to the NFL, the Chicago Bears, the Packers' arch-rivals, were actually closer, 96 miles. Marquette University basketball wasn't yet a big deal, and the closest major team in college football, the University of Wisconsin, was 80 miles away. There was nothing to distract you from baseball.

In contrast, Atlanta got the NFL's Falcons at the same time as the Braves, and this was already announced in June 1965. There was also Georgia Tech football in Atlanta.

And while Milwaukee County Stadium was designed for baseball, Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium was a multipurpose facility, designed to host both baseball and football, and it didn't do a good job with either one, so much so that, by 1997, both the Braves and the Falcons had gotten new stadiums and their 1st home was demolished. (That process is well underway again: In 2017, both teams will abandon their still relatively new stadiums for brand-new ones. Atlanta is a lousy sports town.)

Just another oversized concrete ashtray.

At least it had real grass, not artificial turf.

The Braves leaving Milwaukee? Despite being a winning team? And moving to Atlanta? It didn't seem to make sense. Why would such a successful and popular baseball team move? And why there?

The case for the plaintiff seems ridiculous. Can the defense make a case that outweighs it? (Remember: This is a civil case, where a preponderance of the evidence matters, not the elimination of all reasonable doubt.)

Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame the Milwaukee Braves for Moving to Atlanta

First, let me do some reasons that didn't make the cut: The Best of the Rest.

Beer. The stuff that made Milwaukee famous. Milwaukee wasn't quite a single-industry town in the 1950s and 1960s: It was, and remains, the headquarters of Harley-Davidson motorcycles and Briggs & Stratton automotive components. But brewing dominated the city as much as the auto industry dominated Detroit and the steel industry dominated Pittsburgh and Cleveland.

The Miller brewery, then as now, Milwaukee's biggest

And breweries are good to their employees. A friend of my family worked at the Anheuser-Busch brewery across from Newark Airport for over 40 years. Great benefits, and he now lives on a pension plan that makes General Motors look like Papa Johns.

One benefit of working at a Milwaukee-area brewery in the Fifties was getting a bonus at the end of the month: A free case of beer. Like Henry Ford 40 years earlier, believing that his workers should be able to afford the cars that they built themselves, the breweries rewarded their employees with their own product, free of charge.

A case contained 24 bottles. That's less than 1 free bottle a day. But since an average month of 30 days contains about 22 workdays, that does work out to about 1 free bottle to have at the end of every workday. Pretty soon, a brewery worker got the idea that being asked to pay for beer wasn't such a good idea.

What does this have to do with the Braves? Well, in 1961, the City of Milwaukee passed a law prohibiting fans from bringing outside beer into sports stadiums and arenas. This went over about as well as the City of Philadelphia's ban on bringing outside food into Lincoln Financial Field did when it opened in 2003: Eagles fans, many of them used to bringing in hoagies (what their area calls submarine sandwiches), had a holy fit. Philly sports fans are like Dr. Bruce Banner: You wouldn't like them when they're angry. That ban wasn't lifted until 2009.

Did the beer ban really make much of a difference in Milwaukee? You tell me: In 1960, when the Braves were in the Pennant race most of the way, they averaged 19,452 fans per home game; in 1961, again in the race most of the way, they averaged 14,304. That's a drop of 5,148 per game, or 36 percent. More than 1 out of every 3 fans who went in 1960 stayed home in 1961. Attendance for a Milwaukee-based baseball team wouldn't top 19,452 per game again until 1978, the 1st time the Brewers were in a Pennant race.

So was a Braves game just an excuse to get drunk in public? No, of course not: There are no legends of Braves fans -- or Brewers fans, or Packers fans, or Bucks fans -- engaging in alcohol-fueled rowdy behavior. No booing a man dressed as Santa Claus and throwing things at him, like in Philadelphia in 1968. No "Ten Cent Beer Night" like in Cleveland in 1974. No "Disco Demolition Night" like in Chicago in 1979. And while there were field invasions after Braves and Packers title wins, they weren't as chaotic and outright scary as they became in other cities, especially New York.

Packer fans might get into fights with Chicago Bears fans, but Braves fans in the Fifties and Sixties, and Brewers fans since, don't have the reputation for being drunken boors. They just didn't like seeing what they saw as a work-earned right being taken away, and being forced to pay for stadium beer. So those 5,148 fans decided to stay home, and sit in their easy chairs, and drink the beer they'd already paid for, and the beer they'd received for free, and watch the Braves for free.

Victims of Their Own Success. At the conclusion of the 1959 season, the Braves had rewarded their fans with 3 straight seasons of still having something to play for after Game 154. They had won a World Series and nearly made it back-to-back titles. The Braves were kings in Milwaukee, real-life kings, unlike the retroactively fictional Fonz of the 1970s- & '80s-aired, but late 1950s- and early '60s-set, series Happy Days.

But, having gotten a taste of success, now, they were demanding it, and not getting it. It wasn't that the Braves organization, or players, were taking fans for granted. It was that other teams had adjusted, and were getting to be better.

The Dodgers had rebuilt during the process of moving to Los Angeles. Indeed, as early as their 1953 Pennant in Brooklyn, Don Zimmer and Jim Gilliam, 2 of the players who would become stars in L.A., were beginning to make their mark. The San Francisco Giants had also retooled in anticipation of moving away from New York. The Cincinnati Reds made a serious run at the Pennant in 1956, thanks to young stars like Wally Post and Rookie of the Year Frank Robinson, and their maturing would lead to the 1961 NL Pennant.

Branch Rickey, former president of the Dodgers and the St. Louis Cardinals, was no longer working for the Pittsburgh Pirates, but the team he built won the World Series in 1960, led by Most Valuable Player Dick Groat, Cy Young Award winner Vernon Law, Gold Glove winner and World Series hero Bill Mazeroski, and young star Roberto Clemente. By 1964, the Cardinals had finally figured out that they needed black players to compete with everyone else, and they blossomed with Bob Gibson and Curt Flood becoming stars, and Groat and Lou Brock being obtained in midseason trades.

The Braves were also in transition, as I'll get to in a moment.

Milwaukeeans were used to minor-league ball, then saw the Braves come and be successful quickly, and then fell off just enough to no longer be Pennant winners, and they got angry at the lack of additional Pennants. They'd developed an entitlement complex, much like fans of London soccer team Arsenal were used to finishing 4th or higher being an achievement, and got spoiled between 1996 and 2006, then came to believe that 4th was no longer good enough, and got angry at the very manager, Arsène Wenger, who won them their recent trophies.

Pretty soon, the fans who packed County Stadium 2 million strong every year began to stay home. New team owner Bill Bartholomay didn't say, but could have said, what Giants owner Horace Stoneham said when reminded of the young fans who wouldn't have the Giants in New York after 1957: "I feel bad for the kids, but I haven't seen too many of their fathers lately."

Star Power. Or, Rather, a Lack of It. Who were the Braves' biggest stars? Warren Spahn, a pitcher. Despite the legends of Gibson, Sandy Koufax, Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan, and the shooting stars that were Mark Fidrych and Fernando Valenzuela, pitchers usually don't bring in fans the way sluggers do.

So who were the Braves' heavy hitters? Eddie Mathews, a man born with great talent for hitting a baseball, but not much personality. And Hank Aaron, who was not only a black man in a then mostly-white city (that has changed: In the 2010 Census, the City of Milwaukee became plurality-black), but was described even in the early 1970s, as people began to realize he could become the game's all-time home run leader, as a "quiet superstar."

Aaron was not big on self-promotion. If anything, Midwesterners (at least, until the Braves moved) should have loved Aaron: He was a man who showed up, did his job, did it well, went home, and quietly enjoyed the rewards of his labor. But, as long as the Braves were in Milwaukee, it was the white (and Southern) Mathews who was more popular, not the black (and Southern) Aaron. (In all fairness, Mathews did arrive a year sooner than Aaron, and the fans saw him blossom first.)

In 1964, Spahn's arm had finally accepted its age, Mathews was in decline, and most of the 1957 and '58 stars were gone. Aaron was still there, but the players filling in weren't particularly stellar. Phil Niekro wasn't yet the pitcher that he would become in Atlanta. Joe Torre was already good, but his best years would come in Atlanta and St. Louis. The Braves simply weren't as interesting in the Sixties as they were in the Fifties.

Now, for the Top 5 Reasons:

But Milwaukee simply isn't a very big city. It is, by far, the biggest city in the State of Wisconsin. But as big-league cities go, it's not big. In the 1950 Census, it had 637,000 people. In 1960, it reached its all-time peak of 741,000. But by 1970, when the Brewers arrived, it was down to 717,000, and that decline was already underway when the Braves left in 1965. In 2010, it was down to 595,000 -- only a slight decline from 2000, but a drop of 24 percent from the all-time peak.

And compare Milwaukee's population to the other major U.S. cities in 1960, with cities then having Major League Baseball teams in bold, and the 2 cities in question underlined:

1. New York (just 1 team then, got a 2nd in 1962) 7,781,984

2. Chicago (2 teams) 3,550,404

3. Los Angeles (just 1 team then, got a 2nd in 1962) 2,479,015

4. Philadelphia 2,002,512

--. Toronto 1,919,000 in the Canadian Census of 1961 (got a team in 1977)

5. Detroit 1,670,144

--. Montreal 1,201,559 in the Canadian Census of 1961 (got a team in 1969)

6. Baltimore 939,024

7. Houston (got a team in 1962) 938,219

8. Cleveland 876,050

9. Washington 763,956

10. St. Louis 750,026

11. Milwaukee 741,324

12. San Francisco (just 1 team then, Oakland got a team in 1968) 740,316

13. Boston 697,197

14. Dallas (got a team in 1972) 679,684

15. New Orleans (has never had a major league team) 627,525

16. Pittsburgh 604,332

17. San Antonio (has never had a major league team) 587,718

18. San Diego (got a team in 1969) 573,224

19. Seattle (got a team briefly in 1969 and permanently in 1977) 557,087

20. Buffalo (hasn't had a major league team since 1915) 532,759

21. Cincinnati 502,550

22. Memphis (has never had a major league team) 497,524

23. Denver (got a team in 1993) 493,887

24. Atlanta (got a team in 1966) 487,455

25. Minneapolis (got a team in 1961) 482,872

26. Indianapolis (hasn't had a team since 1915) 476,258

27. Kansas City 475,539

At the time, Milwaukee ranked 11th in U.S. population, and 11th among MLB cities (if you properly divide 2-team Chicago in halves).

Note that, in 1960, Atlanta had just 52 percent of Milwaukee's population. It wasn't even the biggest city in the South: It ranked 6th, 3rd behind New Orleans and Memphis if you don't count Texas. So Atlanta, at first glance, doesn't look like a good destination for a MLB team. But Milwaukee? It doesn't look like a great place for one to stay in, being only the 5th-largest city in the Midwest (6th if you count each half of Chicago).

By 1962, when Bartholomay and his group bought the Braves from Lou Perini, who moved the Braves out of Boston but kept his own residence in there, MLB teams had already been given to Minneapolis and Houston, and additional ones to New York (the Mets) and Los Angeles (the Angels).

Buffalo, Dallas, Denver, Louisville, San Diego, Seattle, Toronto, Montreal and, yes, Atlanta had begun aggressively pursuing teams, either through moves, through AL or NL expansion, or through the since-aborted Continental League.

In 1964, Spahn's arm had finally accepted its age, Mathews was in decline, and most of the 1957 and '58 stars were gone. Aaron was still there, but the players filling in weren't particularly stellar. Phil Niekro wasn't yet the pitcher that he would become in Atlanta. Joe Torre was already good, but his best years would come in Atlanta and St. Louis. The Braves simply weren't as interesting in the Sixties as they were in the Fifties.

Now, for the Top 5 Reasons:

5. Demographics. The Braves were 1 of 2 teams in Boston, but they were the only team in Milwaukee. The Chicago Cubs and the Chicago White Sox were over 90 miles away: If anything, the Braves' arrival in 1953 took fans away from them, and the White Sox' unexpected Pennant of 1959 did nothing to make it the other way around.

But Milwaukee simply isn't a very big city. It is, by far, the biggest city in the State of Wisconsin. But as big-league cities go, it's not big. In the 1950 Census, it had 637,000 people. In 1960, it reached its all-time peak of 741,000. But by 1970, when the Brewers arrived, it was down to 717,000, and that decline was already underway when the Braves left in 1965. In 2010, it was down to 595,000 -- only a slight decline from 2000, but a drop of 24 percent from the all-time peak.

Milwaukee Avenue, downtown, 1965

And compare Milwaukee's population to the other major U.S. cities in 1960, with cities then having Major League Baseball teams in bold, and the 2 cities in question underlined:

1. New York (just 1 team then, got a 2nd in 1962) 7,781,984

2. Chicago (2 teams) 3,550,404

3. Los Angeles (just 1 team then, got a 2nd in 1962) 2,479,015

4. Philadelphia 2,002,512

--. Toronto 1,919,000 in the Canadian Census of 1961 (got a team in 1977)

5. Detroit 1,670,144

--. Montreal 1,201,559 in the Canadian Census of 1961 (got a team in 1969)

6. Baltimore 939,024

7. Houston (got a team in 1962) 938,219

8. Cleveland 876,050

9. Washington 763,956

10. St. Louis 750,026

11. Milwaukee 741,324

12. San Francisco (just 1 team then, Oakland got a team in 1968) 740,316

13. Boston 697,197

14. Dallas (got a team in 1972) 679,684

15. New Orleans (has never had a major league team) 627,525

16. Pittsburgh 604,332

17. San Antonio (has never had a major league team) 587,718

18. San Diego (got a team in 1969) 573,224

19. Seattle (got a team briefly in 1969 and permanently in 1977) 557,087

20. Buffalo (hasn't had a major league team since 1915) 532,759

21. Cincinnati 502,550

22. Memphis (has never had a major league team) 497,524

23. Denver (got a team in 1993) 493,887

24. Atlanta (got a team in 1966) 487,455

25. Minneapolis (got a team in 1961) 482,872

26. Indianapolis (hasn't had a team since 1915) 476,258

27. Kansas City 475,539

At the time, Milwaukee ranked 11th in U.S. population, and 11th among MLB cities (if you properly divide 2-team Chicago in halves).

Note that, in 1960, Atlanta had just 52 percent of Milwaukee's population. It wasn't even the biggest city in the South: It ranked 6th, 3rd behind New Orleans and Memphis if you don't count Texas. So Atlanta, at first glance, doesn't look like a good destination for a MLB team. But Milwaukee? It doesn't look like a great place for one to stay in, being only the 5th-largest city in the Midwest (6th if you count each half of Chicago).

By 1962, when Bartholomay and his group bought the Braves from Lou Perini, who moved the Braves out of Boston but kept his own residence in there, MLB teams had already been given to Minneapolis and Houston, and additional ones to New York (the Mets) and Los Angeles (the Angels).

Buffalo, Dallas, Denver, Louisville, San Diego, Seattle, Toronto, Montreal and, yes, Atlanta had begun aggressively pursuing teams, either through moves, through AL or NL expansion, or through the since-aborted Continental League.

If Bartholomay and his group had rejected Atlanta as a destination, there were other cities they could have moved the Braves to, and other teams looking to move that Atlanta could have chosen from. And if Perini, who had already begun to lose money owning the Braves, hadn't sold them when he did, he would have had to do so at some point, or move them again.

"But, Mike," you might say, "You're citing intracity population figures, not those of the entire metropolitan areas, and that's unfair." And you would be right -- in hindsight. But, at the time, people didn't think that way. It took visionaries to think that way.

Visionaries like team owners Walter O'Malley of the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers (who, despite his vision, used it for greed, and was not a good person), Joan Payson of the Mets, Roy Hofheinz of the Houston Colt .45s/Astros, and the not-always-so-aptly-nicknamed "Foolish Club," the team owners who founded the American Football League in 1960.

And visionaries like sportswriter Jack Murphy of the San Diego Union, who convinced first AFL founder Lamar Hunt and Los Angeles Chargers owner Barron Hilton, and then the National League and NBA owners, that San Diego would be a great city for their leagues.

And visionaries like politicians Hofheinz, a federal judge who had been Mayor of Houston; George Christopher of San Francisco and Norris Poulson of Los Angeles, the Mayors who got the Giants and the Dodgers to come to California; and Ivan Allen Jr. Which leads us to...

"But, Mike," you might say, "You're citing intracity population figures, not those of the entire metropolitan areas, and that's unfair." And you would be right -- in hindsight. But, at the time, people didn't think that way. It took visionaries to think that way.

Visionaries like team owners Walter O'Malley of the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers (who, despite his vision, used it for greed, and was not a good person), Joan Payson of the Mets, Roy Hofheinz of the Houston Colt .45s/Astros, and the not-always-so-aptly-nicknamed "Foolish Club," the team owners who founded the American Football League in 1960.

And visionaries like sportswriter Jack Murphy of the San Diego Union, who convinced first AFL founder Lamar Hunt and Los Angeles Chargers owner Barron Hilton, and then the National League and NBA owners, that San Diego would be a great city for their leagues.

And visionaries like politicians Hofheinz, a federal judge who had been Mayor of Houston; George Christopher of San Francisco and Norris Poulson of Los Angeles, the Mayors who got the Giants and the Dodgers to come to California; and Ivan Allen Jr. Which leads us to...

4. Atlanta. The year the move to Atlanta was announced, 1965, was the high-water mark of the Civil Rights Movement. The Voting Rights Act was signed into law. The Selma-to-Montgomery March had just happened. The Civil Rights Act had been signed into law the year before. The lunch-counter sit-ins, the Freedom Rides, the March On Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and the integrations of the universities of Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama had all taken place, with mixed success in some cases and total success in others. All this had happened within the last 5 years. And Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was the current holder of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Dr. King was from Atlanta. The Mayor at the time was Ivan Allen Jr. He ran his father's office-supply company, and took it to new heights, making himself one of the South's richest men. He lived long enough to get an offer he couldn't refuse: Staples bought him out in 1999, and his son, Inman Allen, still runs one of their office-furniture divisions.

In 1961, Allen ran for Mayor against segregationist Lester Maddox, who would later be elected Governor of Georgia. Allen won, and began to build on the work of his predecessor, William Hartsfield, for whom the city's famous airport is named.

As a businessman, Allen understood that he had the chance to change the image of his city. More than that, he had the chance to help change perceptions of the State of Georgia and of the South itself. The city underwent its greatest construction phase since after its burning in the Civil War 100 years earlier. He built the Memorial (now the Woodruff) Arts Center, in effect Atlanta's version of New York's Lincoln Center. He created MARTA, the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, which reworked the city's bus system, and, after he left office, built its subway. He also got Interstate 285, a beltway, a.k.a. "The Perimeter" and "The O Around the A," built.

He got Atlanta Stadium (later Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium) built and, although it wouldn't open until after he left office, he got the Omni Coliseum approved. This enabled the city to go from no major league teams when he took office on January 1, 1962 to 3 of them when he left on January 1, 1970.

Allen posing inside the stadium his Administration was building, 1964.

It opened in 1965, and hosted the Beatles

before it hosted the Braves or the Falcons.

More low-income housing was built in his 8 years in office than in the previous 30. He needed to do this to alleviate the concerns of local black leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King Sr., that he wasn't doing enough for the poor and was focusing too much on business, especially downtown -- a criticism since leveled at many urban mayors, black and white alike (including Newark's Sharpe James in the 1980s and '90s).

"It is wonderful to be idealistic and to speak about human values," Allen said, "but you are not going to be able to do one thing about them if you are not economically strong. If there is any one slogan I lived by as Mayor of Atlanta, that would be it."

So, with the concerns of both business and civil rights in mind, he brought the 2 concepts together. The day he was sworn in, he ordered all "WHITE" and "COLORED" signs removed from City Hall, and personally desegregated the City Hall cafeteria by dining with local black activists. He desegregated municipal hiring. He hired the city's first black firemen. He let it be known that black Atlanta policemen would be allowed to arrest white criminals. He desegregated the city's pools. By January 1964, 6 months before President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law, 14 Atlanta hotels had already desegregated themselves.

Allen billed Atlanta as "The City Too Busy to Hate." That made the sports establishments stand up and take notice. Atlanta also offered a bigger stadium, if not necessarily a better one, than Milwaukee County Stadium: 52,000 to 44,000. (Milwaukee County Stadium would later expand to 53,000.) Today, the Braves' team museum is named for Allen.

Downtown Atlanta, 1966

But it was more than that. It wasn't just municipal, or even metropolitan. It was regional. There was no other MLB team within 90 miles of Milwaukee, but, within 400 miles -- essentially, a single day's drive -- there were 6 others: 2 in Chicago, and 1 each in Minneapolis, St. Louis, Cincinnati and Detroit. The Braves could only build an identity as "Wisconsin's Team" if they stayed put.

But the nearest big-league cities to Atlanta were all very far away: Cincinnati (461 miles), St. Louis (555), Washington (643), and Houston (799). Even the closer Southern cities that have major league teams in one sport or another today weren't all that close: Charlotte (243), Nashville (248), Jacksonville (347), Memphis (383), Raleigh (400), Orlando (438), Tampa (457), New Orleans (469), Miami (661), Dallas (784), Oklahoma City (849). And, aside from Dallas with the Cowboys, none of them had teams in sports' major leagues yet: The Miami Dolphins would debut in 1966, the New Orleans Saints in 1967.

In other words, if you were a Southerner in 1965, and you wanted to see a big-league baseball game, you had to drive 9 hours (counting rest stops) to get to Cincinnati, find a place to park in the dodgy West End, and sit in tiny Crosley Field. Sportsman's Park in St. Louis and Griffith Stadium in Washington were of similar size (although D.C. Stadium, now RFK Stadium, had been built by that point).

Whereas, from 1966 onward, a person living in the Carolinas, Tennessee, Alabama or Mississippi no longer had to take them newfangled Interstate highways to D.C., Cincy or St. Lou to see a team they could truly call their own: The Braves were The South's Team. True, there were the Astros, and Texas was a Southern State, but they weren't The South's Team, they were Texas' Team.

It's also important to note the timing. On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Race riots broke out in nearly every major American city, including Atlanta. There had already been such riots in New York's Harlem and North Philadelphia in 1964, Los Angeles' Watts in 1965, and the West Side of Chicago and the East Side of Cleveland in 1966.

And, in the span of just a few weeks of the Summer of 1967, there were race riots first in Tampa, then in the South End of Boston, then in the West End of Cincinnati, then on the East Side of Buffalo, then in the Central Ward of Newark, then on the North Side of Minneapolis; then, most devastatingly of all, in Detroit; and finally, on the North Side of the Braves' former home, Milwaukee.

The South began to lose the progress it had made in Northern hearts and minds. The hope that it was putting its racist past behind it faded. The fact that racism had become obvious in the North as well didn't help the South's image.

If the Braves had moved somewhere other than Atlanta, and no other team had moved to Atlanta by April 4, 1968, the MLB expansion announced a few weeks later -- Kansas City, Montreal, San Diego and Seattle were chosen -- would never have admitted Atlanta, or any other Deep South city. Miami, maybe; Atlanta, or New Orleans, or Nashville, or, God forbid, Memphis, the city where Dr. King was struck down, no way. It might have taken until the expansion of 1977 for Atlanta to have gotten a team.

Times have changed. Atlanta is a majority-black town, a "chocolate city." The last 5 Mayors have been black: Maynard Jackson, Andrew Young (followed by Jackson again), Bill Campbell, Shirley Franklin and Kasim Reed. Atlanta has become a major corporate center: Already the world headquarters for Coca-Cola, it also became so for future (now former) Braves owner Ted Turner's media empire including CNN (more about that later), plus Delta Air Lines, United Parcel Service, Home Depot and Newell Rubbermaid -- and it's opened its doors to black business as well as white business.

Downtown Atlanta today

Today, if you include all those places within Atlanta's "market" -- every place in this country where the Braves are the closest MLB team -- they have the most people, about 35 million. That's 12 million more than New York and nearly double that of Los Angeles -- each of which, remember, gets divided between 2 teams.

Milwaukee? Their market is just over 2 million, dead last among MLB's 30 markets if you measure this way, and still last if you measure only by the federally-defined "metropolitan area"; in which case, Atlanta has 6.2 million and ranks 9th, behind L.A,. the 2 New Yorks (if we presume the Tri-State Area is equally divided between the Yankees and the Mets, ha ha), Boston, the Texas Rangers, Philadelphia, Houston and Miami.

Of course, the Milwaukee baseball market used to be a lot bigger. It shrank, thanks to...

3. The Minnesota Twins. When they were established in 1961, they took a lot of territory away from the Braves. The entire State of Minnesota. The entire State of North Dakota. The entire State of South Dakota. Northernmost Iowa. Even the westernmost part of Wisconsin, which is closer to Minneapolis than it is to Milwaukee, or even to Madison. Today, that territory includes about 9.3 million people.

Granted, it was a lot less then. But look at the attendance figures: In 1960, the last year that the Braves had the Upper Midwest all to themselves, they got 19,452 a game; in 1961, the 1st year the Twins were in Minnesota, the Braves got 14,304, while the Twins got 15,611. The newly-arrived Twins, while benefiting from the novelty factor, were still not a good team, yet they got 1,200 more fans a game than the established, successful Braves.

It got worse: In 1962, the Twins finished 2nd. By 1965, they were Pennant winners. True, the Braves were stuck in Milwaukee that year only because of a legal injunction that forced them to finish their County Stadium lease, resulting in a lame-duck attendance of 6,859 fans per game. But the Twins were now successful competitively and financially.

People from Minnesota, the Dakotas, Northern Iowa and Western Wisconsin no longer needed to go all the way to Milwaukee to see a good big-league ballclub. The Twins were closer. Eau Claire was 242 miles from West Milwaukee, but only 94 miles from Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington.

Sioux Falls, South Dakota was 498 miles from the Braves, 231 miles from the Twins. Fargo, North Dakota was 568 miles from the Braves, 246 miles from the Twins. Sioux City, Iowa was 468 miles from the Braves, 265 miles from the Twins. Granted, the Dakotas and Iowa still weren't close, but they were a whole lot closer to Harmon Killebrew and Tony Oliva than they were to Aaron and Mathews.

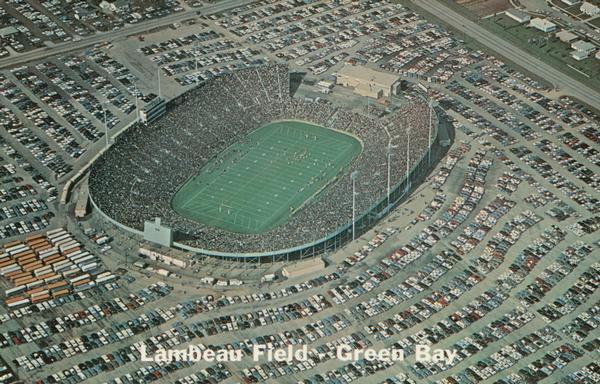

2. Vince Lombardi. In spite of the Braves' wild attendance in their 1st few years -- tame though it sounds in hindsight, it was spectacular for the time -- Wisconsin is, first and foremost, a football State.

When the Braves arrived in 1953, the Green Bay Packers were in the middle of a down period. They hadn't reached, let alone won, the NFL Championship Game since 1944. As late as 1958, they were just 1-10-1.

But in 1959, Vince Lombardi was named the Packers' head coach and general manager. Right after the Braves fell just short in a bid for a 3rd straight Pennant, the Packers jumped to 7-5 under Lombardi's leadership. In 1960, they won the NFL Western Division. In 1961, they began a run of 5 NFL Championships in 7 seasons. During that run, the Braves moved.

It wasn't just the arrival of the Twins that cut into the Braves' attendance: It was the Pack's return to glory under Lombardi. Fans in Wisconsin who could only afford to go to 1 major league sporting event a year chose to head for Green Bay to watch the Packers at Lambeau Field, instead of for Milwaukee to watch the Braves at County Stadium.

Except that the Packers did play at County Stadium. From 1933 until 1952, every season, the Packers played 2 of their 6 home games at Borchert Field, home of the old minor-league Milwaukee Brewers. From 1953 until 1960, they played 2 out of 6 at County Stadium. From 1961 to 1977, 2 out of 7. From 1978 to 1994, 3 out of 8.

They also annually played a preseason game in Milwaukee. They even played the 1939 NFL Championship Game at the Dairy Bowl in the Milwaukee suburb of West Allis (now an auto racing track called the Milwaukee Mile), and a 1967 NFL Divisional Playoff at County Stadium.

It was the economics (Lambeau now far exceeded County Stadium's seating capacity) and the logistics of playing home games away from Green Bay that made them play at Lambeau only from 1995 onward. But that was under general manager Ron Wolf and head coach Mike Holmgren.

Lombardi might have had the power to cut Milwaukee out of the Pack's schedule, but he probably liked the idea of having 2 home fields. (Three, if you count the preseason game the Packers played every year at the University of Wisconsin's Camp Randall Stadium. While they don't play in Milwaukee anymore, not even in the preseason, they do still play a preseason game at Camp Randall.)

He probably liked the idea of having not just "small-town America" loving his team (Green Bay had only about 60,000 people at the time, and the Packers became what the Cowboys only claimed later, "America's Team"), but also having a "big city" (even if, as I pointed out earlier, Milwaukee wasn't that big a city) rooting for his team.

In other words, despite the 117-mile difference between downtown Milwaukee and Lambeau Field, the Packers were very much a part of Milwaukee's culture. Although they haven't played a regular-season game there in 21 seasons, they still are.

But none of those is the biggest reason the Braves moved when they did, or where they did.

1. Television. Baseball was slow to accept TV. With some reason: While radio grew the local fan base, TV only grew the national one, not the local one. Why go 300, or even 3, miles to pay to see a ballgame, and pay for food at the ballpark, when you can sit at home, watching for free, eating food and drinking beer that you've already paid for? This, along with raids by major league teams, killed the Negro Leagues, and it devastated the minor leagues. (MLB's expansion didn't exactly help the minors, either.)

As late as 1961, the Braves allowed none of their games to be televised. Zero. That may have been the biggest reason for the high attendance, especially since the novelty factor had worn off: If you wanted to see the Braves, you had to actually be inside County Stadium.

In 1962, shortly before selling the team to Bartholomay, Perini signed a deal to allow the broadcast of 15 away games on local TV. In 1963, Bartholomay allowed more away games and, critically, 5 home games. Attendance dropped. In 1964, the Braves lost $500,000 -- about $3.8 million in today's money, not much in the current baseball climate, but a huge amount then.

In contrast, the Southern TV market seemed like a gold mine. Since places like Charlotte, Nashville, Memphis, Little Rock, New Orleans, Jackson, Jacksonville and Birmingham seemed too for from Atlanta to drive, Bartholomay figured the TV revenue would be huge, and wouldn't drive down attendance. It seemed like a great excuse to move the team, and to move it to Atlanta.

There was just one problem: It didn't work. The Braves' attendance improved their first few years in Atlanta over their last couple of years in Milwaukee, but that was due to the novelty factor and the Braves being good (winning the 1st NL Western Division title in 1969). By the early 1970s, with Aaron their only bankable star -- and a black man whom the Braves simply couldn't make appeal to white fans without the novelty of the chase for the record, attendance seriously lagging until he got to 712 in late '73 and dropping off completely after he got to 715 in early '74 -- their attendance was in the tank, and the TV revenue simply wasn't covering it.

Meanwhile, MLB had returned to Milwaukee with the Brewers, and, while they weren't good, they were less embarrassing to Milwaukee than the Braves were to Atlanta.

In 1975, Bartholomay's group sold its majority stock in the Braves to Ted Turner, who was looking to grow his media empire. It took another few years, but he did make it work, once he turned his single TV station, WTBS-Channel 17, into a cable "Superstation," making it a national network based on movies and the Braves.

In 1982, the Braves won the NL West, and millions of Americans who had never set foot in Dixie became Braves fans. Sports Illustrated put MVP-in-the-making Dale Murphy on the cover, and headlined the Braves as "AMERICA'S TEAM II."

A similar phenomenon happened 2 years later, when the Chicago Cubs won the NL East, and their games were broadcast nationally on WGN, by then also a "superstation." It had even happened before, with KMOX anchoring a regional radio network that had made the Cardinals the South's team. To this day, there are lots of Southerners whose MLB taste runs toward St. Louis rather than toward Atlanta, as the Cards were handed down from father to son to grandson.

Even as the Braves fell off in 1984, the year of the Cubs' success on the field and on the nationwide air, TBS' ratings for their games remained good. When they started winning again in 1991, the ratings jumped again, and they've remained strong.

Metropolitan Stadium, home of the Twins and Vikings, 1961 to 1981

2. Vince Lombardi. In spite of the Braves' wild attendance in their 1st few years -- tame though it sounds in hindsight, it was spectacular for the time -- Wisconsin is, first and foremost, a football State.

When the Braves arrived in 1953, the Green Bay Packers were in the middle of a down period. They hadn't reached, let alone won, the NFL Championship Game since 1944. As late as 1958, they were just 1-10-1.

But in 1959, Vince Lombardi was named the Packers' head coach and general manager. Right after the Braves fell just short in a bid for a 3rd straight Pennant, the Packers jumped to 7-5 under Lombardi's leadership. In 1960, they won the NFL Western Division. In 1961, they began a run of 5 NFL Championships in 7 seasons. During that run, the Braves moved.

"Those who stay will be champions," Lombardi told his players.

The Packers stayed, and were champions.

The Braves were no longer champions, and they did not stay.

Lambeau Field, as it appeared in the Lombardi era

Except that the Packers did play at County Stadium. From 1933 until 1952, every season, the Packers played 2 of their 6 home games at Borchert Field, home of the old minor-league Milwaukee Brewers. From 1953 until 1960, they played 2 out of 6 at County Stadium. From 1961 to 1977, 2 out of 7. From 1978 to 1994, 3 out of 8.

They also annually played a preseason game in Milwaukee. They even played the 1939 NFL Championship Game at the Dairy Bowl in the Milwaukee suburb of West Allis (now an auto racing track called the Milwaukee Mile), and a 1967 NFL Divisional Playoff at County Stadium.

County Stadium hosting its last Packer game, December 18, 1994.

They won 21-17. With some irony, their opponents

were the Atlanta Falcons. Attendance: 54,885.

It was the economics (Lambeau now far exceeded County Stadium's seating capacity) and the logistics of playing home games away from Green Bay that made them play at Lambeau only from 1995 onward. But that was under general manager Ron Wolf and head coach Mike Holmgren.

Lombardi might have had the power to cut Milwaukee out of the Pack's schedule, but he probably liked the idea of having 2 home fields. (Three, if you count the preseason game the Packers played every year at the University of Wisconsin's Camp Randall Stadium. While they don't play in Milwaukee anymore, not even in the preseason, they do still play a preseason game at Camp Randall.)

He probably liked the idea of having not just "small-town America" loving his team (Green Bay had only about 60,000 people at the time, and the Packers became what the Cowboys only claimed later, "America's Team"), but also having a "big city" (even if, as I pointed out earlier, Milwaukee wasn't that big a city) rooting for his team.

In other words, despite the 117-mile difference between downtown Milwaukee and Lambeau Field, the Packers were very much a part of Milwaukee's culture. Although they haven't played a regular-season game there in 21 seasons, they still are.

But none of those is the biggest reason the Braves moved when they did, or where they did.

1. Television. Baseball was slow to accept TV. With some reason: While radio grew the local fan base, TV only grew the national one, not the local one. Why go 300, or even 3, miles to pay to see a ballgame, and pay for food at the ballpark, when you can sit at home, watching for free, eating food and drinking beer that you've already paid for? This, along with raids by major league teams, killed the Negro Leagues, and it devastated the minor leagues. (MLB's expansion didn't exactly help the minors, either.)

NBC's Peacock logo, advertising programming "in living color"

As late as 1961, the Braves allowed none of their games to be televised. Zero. That may have been the biggest reason for the high attendance, especially since the novelty factor had worn off: If you wanted to see the Braves, you had to actually be inside County Stadium.

In 1962, shortly before selling the team to Bartholomay, Perini signed a deal to allow the broadcast of 15 away games on local TV. In 1963, Bartholomay allowed more away games and, critically, 5 home games. Attendance dropped. In 1964, the Braves lost $500,000 -- about $3.8 million in today's money, not much in the current baseball climate, but a huge amount then.

A CBS tag of 1965, including their "Eye" logo

In contrast, the Southern TV market seemed like a gold mine. Since places like Charlotte, Nashville, Memphis, Little Rock, New Orleans, Jackson, Jacksonville and Birmingham seemed too for from Atlanta to drive, Bartholomay figured the TV revenue would be huge, and wouldn't drive down attendance. It seemed like a great excuse to move the team, and to move it to Atlanta.

ABC logo, 1965

There was just one problem: It didn't work. The Braves' attendance improved their first few years in Atlanta over their last couple of years in Milwaukee, but that was due to the novelty factor and the Braves being good (winning the 1st NL Western Division title in 1969). By the early 1970s, with Aaron their only bankable star -- and a black man whom the Braves simply couldn't make appeal to white fans without the novelty of the chase for the record, attendance seriously lagging until he got to 712 in late '73 and dropping off completely after he got to 715 in early '74 -- their attendance was in the tank, and the TV revenue simply wasn't covering it.

Meanwhile, MLB had returned to Milwaukee with the Brewers, and, while they weren't good, they were less embarrassing to Milwaukee than the Braves were to Atlanta.

In 1975, Bartholomay's group sold its majority stock in the Braves to Ted Turner, who was looking to grow his media empire. It took another few years, but he did make it work, once he turned his single TV station, WTBS-Channel 17, into a cable "Superstation," making it a national network based on movies and the Braves.

Turner and Bartholomay

In 1982, the Braves won the NL West, and millions of Americans who had never set foot in Dixie became Braves fans. Sports Illustrated put MVP-in-the-making Dale Murphy on the cover, and headlined the Braves as "AMERICA'S TEAM II."

A similar phenomenon happened 2 years later, when the Chicago Cubs won the NL East, and their games were broadcast nationally on WGN, by then also a "superstation." It had even happened before, with KMOX anchoring a regional radio network that had made the Cardinals the South's team. To this day, there are lots of Southerners whose MLB taste runs toward St. Louis rather than toward Atlanta, as the Cards were handed down from father to son to grandson.

Even as the Braves fell off in 1984, the year of the Cubs' success on the field and on the nationwide air, TBS' ratings for their games remained good. When they started winning again in 1991, the ratings jumped again, and they've remained strong.

The Braves, like the Cardinals, the Cubs, the Yankees, the Red Sox and the Dodgers, have a national fan base. And it's thanks to Ted Turner and TBS. He made Bartholomay's dream of the Braves becoming a regional powerhouse not only come true, but get blown right past, all the way to national stardom.

And that never would have happened had the Braves remained in Milwaukee. To this day, the 1957 World Series remains the only one ever won by a Milwaukee baseball team. The building of Miller Park and the Selig family's sale of the team to a group led by Mark Attanasio -- ironically, born right after the Braves won that 1957 Pennant -- has secured the Brewers' long-term future in Milwaukee. But the Brewers, even at their best (the 1982 Pennant season, the Playoff runs of 2008 and 2011), have never been as good, or as interesting, or as profitable as the post-Bartholomay Braves.

So, can Bartholomay and his group be blamed for moving the Braves from Milwaukee to Atlanta?

VERDICT: Guilty. Yes, you can blame them. As Ted Turner himself likes to say, "Either lead, follow, or get out of the way." The Bartholomay group's dream came true, but only many years after the fact: It was only after they got out of the way and let Turner lead that people began to follow.

If, in 1962, the Bartholomay group and the people of Wisconsin were told what would happen between then and 2015, they might reason that things turned out all right, because Milwaukee did get a new team, even if that team had been disappointing.

But if, in 1962, they were only told what would happen between then and 1981, when the Brewers made the Playoffs for the 1st time, with the Braves having made the Playoffs exactly once and not yet having become a national phenomenon, or even a regional one, they would have said, "See? It didn't work. Stay put, you'll be better off."

And, through 1981, that would have been a reasonable presumption. The Braves succeeded after -- long after -- leaving Milwaukee for Atlanta. The Bartholomay group did not.

And that never would have happened had the Braves remained in Milwaukee. To this day, the 1957 World Series remains the only one ever won by a Milwaukee baseball team. The building of Miller Park and the Selig family's sale of the team to a group led by Mark Attanasio -- ironically, born right after the Braves won that 1957 Pennant -- has secured the Brewers' long-term future in Milwaukee. But the Brewers, even at their best (the 1982 Pennant season, the Playoff runs of 2008 and 2011), have never been as good, or as interesting, or as profitable as the post-Bartholomay Braves.

So, can Bartholomay and his group be blamed for moving the Braves from Milwaukee to Atlanta?

VERDICT: Guilty. Yes, you can blame them. As Ted Turner himself likes to say, "Either lead, follow, or get out of the way." The Bartholomay group's dream came true, but only many years after the fact: It was only after they got out of the way and let Turner lead that people began to follow.

If, in 1962, the Bartholomay group and the people of Wisconsin were told what would happen between then and 2015, they might reason that things turned out all right, because Milwaukee did get a new team, even if that team had been disappointing.

But if, in 1962, they were only told what would happen between then and 1981, when the Brewers made the Playoffs for the 1st time, with the Braves having made the Playoffs exactly once and not yet having become a national phenomenon, or even a regional one, they would have said, "See? It didn't work. Stay put, you'll be better off."

And, through 1981, that would have been a reasonable presumption. The Braves succeeded after -- long after -- leaving Milwaukee for Atlanta. The Bartholomay group did not.

2 comments:

Mike, when you talked about Ivan Allen, Jr.'s mayoralship, this was left out: in 1962, he had to deal with the crash of Air France Flight 007, a Boeing 707 which crashed on takeoff from Orly Airport in Paris and killed 130 of the 132 passengers and crew aboard (2 stewardesses who had been sitting in the rear survived); 106 of the passengers were members of the Atlanta Art Association who had been taking a tour of Europe (the Woodruff Arts Center was founded in 1968 in memory of those who died in the crash, and is home to the Alliance Theatre, the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, and the High Museum of Art). Many of the dead were personal friends of Allen, and he went to Europe to identify and help bring home the bodies of the dead. The crash arguably played a large part into turning Atlanta into the city it became...

Just my .02.

I'm curious as to why you think so. Did Allen use this opportunity to help improve the airport, making it the terminal it became? Did he use it to make Atlanta a better city for the arts?

Post a Comment