Today, I look at the first big move in modern baseball: The Boston Braves to Milwaukee just before the 1953 season.

(The Seattle Pilots moved to become the Milwaukee Brewers right before the 1970 season. Such a move would never be permitted today. It would be a logistical nightmare. It could only be approved for the following season.)

Some of these will be easy to figure out -- and thus deliver a verdict of "Not Guilty." Others, not so much.

The case for the Braves staying in Boston was actually stronger than you might think. They had won the Pennant as recently as 1948. They still had Warren Spahn, a Hall of Fame pitcher. They had Eddie Mathews, who turned out to be a Hall of Fame 3rd baseman, coming off a good rookie season. They had Hank Aaron, who turned out to be a Hall of Fame right fielder, in their farm system. Many of the other players who would win Pennants in Milwaukee in 1957 and '58 were also in their farm system.

And the Red Sox? What was the point of going there? They had one bankable star: Ted Williams. At the end of the 1952 season, Williams was in the U.S. Marine Corps, flying a jet in the Korean War. He wouldn't be back until late 1953 -- and no one knew that would be the case in the preceding winter. For all they knew, he could have missed all of '53, '54, and so on... maybe even retire.

After all, at the dawn of the '53 season, he was 34, and while his batting eye came back when he returned from World War II, he was 27 then, so we're talking about a big difference. No one knew that he would have a career year, by most people's standards, at age 42 (his last), or that he would flirt with .400 again at 39 (finishing at .388 in 1957).

Of course, the Red Sox had Fenway Park. But Fenway wasn't considered special in the early Fifties. There were 16 teams playing in 14 ballparks (there was groundsharing in Philadelphia and St. Louis), and 12 of the parks -- all but Yankee Stadium and Cleveland Municipal Stadium -- were built between 1909 and 1915. Fenway has been at least tied for the oldest MLB stadium since Comiskey Park in Chicago closed in 1990, but in 1952, its age (40 years old) didn't make it special: 8 of the other 13 opened in April 1912 or earlier.

Nor did its big, close green wall in left field: Ebbets Field in Brooklyn and Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia had big, close green walls in right field. The hand-operated scoreboard? Until Yankee Stadium went electric in 1950, they all had them. The other things that make Fenway special now? Not there. The CITGO sign? Didn't go up until 1965. The Yawkeys' initials in Morse code on the scoreboard? 1976. The bleachers on top of the Green Monster? 2002.

Fenway wasn't beloved then. As late as 1967, Tom Yawkey said he wanted a new ballpark, or he might move the team. That was the Impossible Dream Pennant season. If the Sox hadn't brought the fans back that season, by 1971, the Sox could well have been sharing an antiseptic ashtray in Foxboro with the New England Patriots -- or have left Boston without a team.

No, the Red Sox weren't special because of their players, or their ballpark, or their history. They hadn't won the World Series since 1918, and as for their 1946 Pennant, well, the Braves had won one more recently. Neither team was a glamour team, but the Braves were, at the least, not far behind the Sox by that measure.

If the Braves had just hung on in Boston one more season, they would have had Mathews' 47 home runs (or thereabouts; Braves Field was roughly as hitter-pitcher balanced as Milwaukee County Stadium), and the attendance would have gone up. One more, and Aaron would have arrived. The team was getting better.

So was the decision to move the right one? I'll give you my top 5 reasons why it might have been.

Of course, the Red Sox had Fenway Park. But Fenway wasn't considered special in the early Fifties. There were 16 teams playing in 14 ballparks (there was groundsharing in Philadelphia and St. Louis), and 12 of the parks -- all but Yankee Stadium and Cleveland Municipal Stadium -- were built between 1909 and 1915. Fenway has been at least tied for the oldest MLB stadium since Comiskey Park in Chicago closed in 1990, but in 1952, its age (40 years old) didn't make it special: 8 of the other 13 opened in April 1912 or earlier.

Nor did its big, close green wall in left field: Ebbets Field in Brooklyn and Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia had big, close green walls in right field. The hand-operated scoreboard? Until Yankee Stadium went electric in 1950, they all had them. The other things that make Fenway special now? Not there. The CITGO sign? Didn't go up until 1965. The Yawkeys' initials in Morse code on the scoreboard? 1976. The bleachers on top of the Green Monster? 2002.

Fenway wasn't beloved then. As late as 1967, Tom Yawkey said he wanted a new ballpark, or he might move the team. That was the Impossible Dream Pennant season. If the Sox hadn't brought the fans back that season, by 1971, the Sox could well have been sharing an antiseptic ashtray in Foxboro with the New England Patriots -- or have left Boston without a team.

No, the Red Sox weren't special because of their players, or their ballpark, or their history. They hadn't won the World Series since 1918, and as for their 1946 Pennant, well, the Braves had won one more recently. Neither team was a glamour team, but the Braves were, at the least, not far behind the Sox by that measure.

If the Braves had just hung on in Boston one more season, they would have had Mathews' 47 home runs (or thereabouts; Braves Field was roughly as hitter-pitcher balanced as Milwaukee County Stadium), and the attendance would have gone up. One more, and Aaron would have arrived. The team was getting better.

So was the decision to move the right one? I'll give you my top 5 reasons why it might have been.

Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame the Boston Braves for Moving to Milwaukee

First, though, a couple of reasons that didn't make the cut: The Best of the Rest:

Arthur Soden. The founder of the Braves, one of the founders of both the National Association in 1871 and the National League in 1876, and probably the man whose money, charity to his fellow owners, kept the NL in business during the Players' League War of 1890, he oversaw 12 Pennants (4 in the NA, 8 in the NL). He was the most successful sports team owner of the 19th Century. Considering all of this, it's a bit surprising that he's not in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

But in 1901, he made a historic blunder. He raised ticket prices, and the newcomers, the Boston Americans of the new American League (they would adapt the old name of Red Stockings and become the Red Sox in 1907), established prices at the level from which he raised them.

Fans of the "Beaneaters," many of them working-class Irish-Catholics who weren't exactly rolling in dough, including the Royal Rooters fan club established by local saloonkeeper Michael T. "Nuf Ced" McGreevy, were infuriated. They abandoned the NL outfit, and made the short walk over to the Huntington Avenue Grounds, where the Americans had set up shop. When Fenway Park opened in 1912, a bit of a walk away, this did not deter them: They remained Red Sox fans, and never went back to the Braves.

From the moment the locals saw that the Red Sox were charging the same old ticket prices, and Arthur Soden wasn't, the Braves were never again the most popular baseball team in Boston -- not even in their Pennant seasons of 1914 and 1948. No one knew it at the time, but Soden had sown the seeds of the Braves' demise.

Politics. James Michael Curley and John F. "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald, who both served in Congress and as Mayor of Boston, were rivals. They didn't like each other. But they both loved baseball, and both switched to the AL team when Soden raised ticket prices.

Both loved to be seen at Huntington Avenue, and then at Fenway. Indeed, when Fenway opened on April 20, 1912, Honey Fitz was Mayor, and he threw out the ceremonial first ball. (Curley was then in Congress.) The Braves couldn't match the star power of these beloved Mayors.

In 1946, Curley was back in Congress, and was elected to a 4th term as Mayor -- possibly helped by his appearances at Fenway Park during the World Series. His successor in Congress? Fitzgerald's grandson, John F. Kennedy. But when the Braves won the Pennant in 1948, did Mayor Curley go to Braves Field? He did not.

Now for the Top 5:

5. Demographics. The end of World War II meant that the troops came back and resumed their habit of going to games. But it also meant that they were taking advantage of the G.I. Bill, and buying houses in the suburbs.

And cars. This meant that it would be harder for fans to drive in to the city for the games. And while both Fenway Park and Braves Field were accessible by what's now known as the Green Line B train, highway access -- despite U.S. Route 20, now part of the Massachusetts Turnpike, going right past both of them -- wasn't very good. And parking in Boston has always been a problem.

Check out these per-game attendance figures for the Boston teams for the last 7 years of their coexistence, between the 1st postwar season and the last season that they were in Boston together:

Year Braves Red Sox

1946 12,593 18,166

1947 16,589 17,621

1948 19,151 19,985

1949 14,049 20,736

1950 11,954 17,456

1951 6,250 17,497

1952 3,653 14,490

No, you're not reading that wrong: The Braves averaged three thousand, six hundred fifty-three fans per home game in 1952. And the economy was good at the time.

And while the Korean War did take quite a few ballplayers (including the Yankees' Whitey Ford and Jerry Coleman, the Giants' Willie Mays, the Dodgers' Don Newcombe and, yes, the Red Sox' Ted Williams), it didn't take anywhere near as many men as did World War II, so that's not a viable excuse. And the Sox outdrew the Braves in every one of those seasons, even 1948, when the Braves won the Pennant and the Sox lost it in a Playoff.

The Sox' average attendance actually went down after the Braves left, and didn't start going up again until the Impossible Dream year, 1967, doubling from 10,014 to 21,331. They never topped 2 million fans in a season until 1977, and didn't start regularly drawing that many until the Pennant season of 1986, missing it only once since (the strike-shortened season of 1994).

Today, we can look at the 6 New England States (minus the corner of Connecticut that tilts toward New York) and see a "market" of 12 million people. Back then, people didn't think in terms of "markets" or even "metropolitan areas."

Could New England support 2 major league teams today? Maybe: Even in losing seasons in 2014 and '15, the Sox have drawn over 35,000 fans per game (or say they have). Although once David Ortiz and his steroids retire, the Sox may see attendance drop like his power after he was exposed in 2009. It's happened before: Yankee attendance dropped after Mickey Mantle retired in 1969, and again in 2015 after Derek Jeter did. Baltimore Oriole attendance sank after Cal Ripken retired in 2001.

But in 1952, Boston and environs could not support 2 teams. Clearly, either the Red Sox or the Braves were going to have to go.

4. Rivalries. Today, we take New York vs. Boston for granted, in all sports. Yankees vs. Red Sox. Jets in the regular season, and Giants in 2 Super Bowls, vs. Patriots. Knicks vs. Celtics. Rangers vs. Bruins.

That was not the case in 1952. There were no Patriots -- or Jets, for that matter. The Celtics hadn't yet reached their 1st NBA Finals. And even Yanks-Sox had cooled off after the heady days of the late 1940s.

The Braves? Who were their arch-rivals? The New York Giants? The Brooklyn Dodgers? Nope, those teams' rivals were each other. The Philadelphia Phillies? Nope. Boston vs. Philadelphia has been a rivalry in basketball since the late 1950s and in hockey since the early 1970s, but it hasn't been one in baseball since the 1910s, when the Sox and the Philadelphia Athletics combined for 8 of the decade's 10 AL Pennants, before Connie Mack had his fire sale after 1914 and Harry Frazee began his in 1919.

The Red Sox and A's wouldn't both be good again until the early 1970s. The Braves and Phillies? They wouldn't both be good again until 1964, when the Phils and the Milwaukee Braves were 2 of the 5 teams that finished in a bunch in the National League standings.

By moving to Milwaukee, the Braves had a built-in geographic rivalry, and thus an easy roadtrip for each team's fans, and thus increasing attendance, with the Chicago Cubs: It's just 90 miles from Wrigley Field to Miller Park (which was built adjacent to County Stadium), more than half as close as Boston is to the next-closest MLB city, New York.

(A lot of people don't realize this, but Baltimore is closer to New York than Boston is. So is Washington, although it hasn't been an AL city and thus a regular Yanks opponent since 1971. Philadelphia, with whom the Mets finally began a real rivalry only a few years ago, is half as close to New York as Boston, but still not as close as Chicago and Milwaukee.)

As it turned out, the rivalry the Braves ended up developing after the move was not with the Cubs, but with the Dodgers. The Braves' move, and the results thereof, helped inspire Walter O'Malley to move the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles. Between 1955 and 1959, either the Braves or the Dodgers finished 1st every year. In '59, they both did, and a Playoff was needed to decide the Pennant. (The Dodgers won.) The Braves and Cubs wouldn't both be good again until 1969, by which point the Braves had moved to Atlanta. (I'll do that one in a later post.)

But aside from Brewers management, the people happiest about the Brewers' shift from the AL to the NL in 1998 were Cub fans, who once again had a roadtrip to Milwaukee. (Chicago White Sox fans didn't like that, as they lost their obvious rivals, but then, their rivalries with Cleveland and Detroit have improved since then.)

3. Ballparks. Braves Field opened in 1915, with 40,000 seats. It was the largest and most modern stadium ever built for baseball to that time.

And cars. This meant that it would be harder for fans to drive in to the city for the games. And while both Fenway Park and Braves Field were accessible by what's now known as the Green Line B train, highway access -- despite U.S. Route 20, now part of the Massachusetts Turnpike, going right past both of them -- wasn't very good. And parking in Boston has always been a problem.

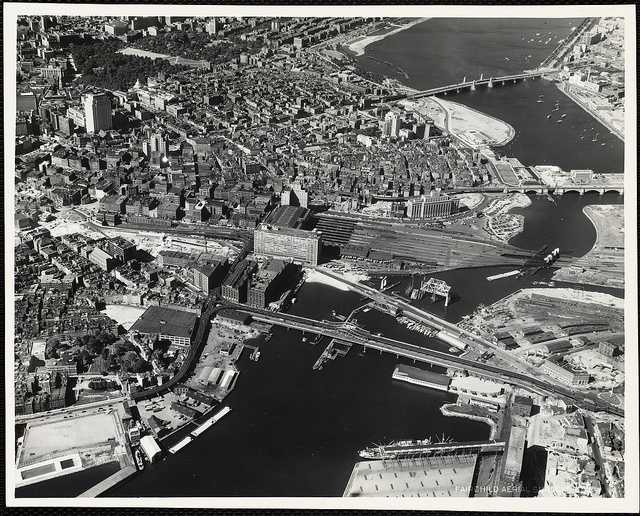

Boston, circa 1950

Check out these per-game attendance figures for the Boston teams for the last 7 years of their coexistence, between the 1st postwar season and the last season that they were in Boston together:

Year Braves Red Sox

1946 12,593 18,166

1947 16,589 17,621

1948 19,151 19,985

1949 14,049 20,736

1950 11,954 17,456

1951 6,250 17,497

1952 3,653 14,490

No, you're not reading that wrong: The Braves averaged three thousand, six hundred fifty-three fans per home game in 1952. And the economy was good at the time.

And while the Korean War did take quite a few ballplayers (including the Yankees' Whitey Ford and Jerry Coleman, the Giants' Willie Mays, the Dodgers' Don Newcombe and, yes, the Red Sox' Ted Williams), it didn't take anywhere near as many men as did World War II, so that's not a viable excuse. And the Sox outdrew the Braves in every one of those seasons, even 1948, when the Braves won the Pennant and the Sox lost it in a Playoff.

The Sox' average attendance actually went down after the Braves left, and didn't start going up again until the Impossible Dream year, 1967, doubling from 10,014 to 21,331. They never topped 2 million fans in a season until 1977, and didn't start regularly drawing that many until the Pennant season of 1986, missing it only once since (the strike-shortened season of 1994).

Today, we can look at the 6 New England States (minus the corner of Connecticut that tilts toward New York) and see a "market" of 12 million people. Back then, people didn't think in terms of "markets" or even "metropolitan areas."

Could New England support 2 major league teams today? Maybe: Even in losing seasons in 2014 and '15, the Sox have drawn over 35,000 fans per game (or say they have). Although once David Ortiz and his steroids retire, the Sox may see attendance drop like his power after he was exposed in 2009. It's happened before: Yankee attendance dropped after Mickey Mantle retired in 1969, and again in 2015 after Derek Jeter did. Baltimore Oriole attendance sank after Cal Ripken retired in 2001.

But in 1952, Boston and environs could not support 2 teams. Clearly, either the Red Sox or the Braves were going to have to go.

4. Rivalries. Today, we take New York vs. Boston for granted, in all sports. Yankees vs. Red Sox. Jets in the regular season, and Giants in 2 Super Bowls, vs. Patriots. Knicks vs. Celtics. Rangers vs. Bruins.

That was not the case in 1952. There were no Patriots -- or Jets, for that matter. The Celtics hadn't yet reached their 1st NBA Finals. And even Yanks-Sox had cooled off after the heady days of the late 1940s.

The Braves? Who were their arch-rivals? The New York Giants? The Brooklyn Dodgers? Nope, those teams' rivals were each other. The Philadelphia Phillies? Nope. Boston vs. Philadelphia has been a rivalry in basketball since the late 1950s and in hockey since the early 1970s, but it hasn't been one in baseball since the 1910s, when the Sox and the Philadelphia Athletics combined for 8 of the decade's 10 AL Pennants, before Connie Mack had his fire sale after 1914 and Harry Frazee began his in 1919.

The Red Sox and A's wouldn't both be good again until the early 1970s. The Braves and Phillies? They wouldn't both be good again until 1964, when the Phils and the Milwaukee Braves were 2 of the 5 teams that finished in a bunch in the National League standings.

By moving to Milwaukee, the Braves had a built-in geographic rivalry, and thus an easy roadtrip for each team's fans, and thus increasing attendance, with the Chicago Cubs: It's just 90 miles from Wrigley Field to Miller Park (which was built adjacent to County Stadium), more than half as close as Boston is to the next-closest MLB city, New York.

(A lot of people don't realize this, but Baltimore is closer to New York than Boston is. So is Washington, although it hasn't been an AL city and thus a regular Yanks opponent since 1971. Philadelphia, with whom the Mets finally began a real rivalry only a few years ago, is half as close to New York as Boston, but still not as close as Chicago and Milwaukee.)

As it turned out, the rivalry the Braves ended up developing after the move was not with the Cubs, but with the Dodgers. The Braves' move, and the results thereof, helped inspire Walter O'Malley to move the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles. Between 1955 and 1959, either the Braves or the Dodgers finished 1st every year. In '59, they both did, and a Playoff was needed to decide the Pennant. (The Dodgers won.) The Braves and Cubs wouldn't both be good again until 1969, by which point the Braves had moved to Atlanta. (I'll do that one in a later post.)

But aside from Brewers management, the people happiest about the Brewers' shift from the AL to the NL in 1998 were Cub fans, who once again had a roadtrip to Milwaukee. (Chicago White Sox fans didn't like that, as they lost their obvious rivals, but then, their rivalries with Cleveland and Detroit have improved since then.)

3. Ballparks. Braves Field opened in 1915, with 40,000 seats. It was the largest and most modern stadium ever built for baseball to that time.

This is a rare color photo of Braves Field. As you can see, the left field pavilion has been removed, and temporary bleachers set up for Boston University football. In 1955, it would all be demolished, except for the right field pavilion, which became the home side of Nickerson Field, BU's stadium; and the Spanish-style ticket booth, behind right field, now BU's police headquarters.

Just 8 years later, Yankee Stadium opened, and suddenly Braves Field (and all other ballparks) were obsolete. A few of them expanded, but, by 1952, Braves Field was still a single-decked stadium that could have been expanded beyond 40,000 fans -- if the demand were there, and if the money was there. But Braves owner Lou Perini didn't have the money, and he didn't have the demand. And, as I said, the parking situation was awful.

In contrast, Milwaukee County Stadium was nearing readiness: It would open in April 1953 with 35,000 seats, and would have 44,000 by Opening Day 1954. (It was expanded in 1973 to 53,192.) It also had 12,000 parking spaces, to cater to all those people coming in from Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and the Dakotas.

County Stadium during the 1957 World Series

Moving to Milwaukee (where, keep in mind, the Braves had their top farm team, so they wouldn't have to pay anybody off to move there) instantly vaulted the Braves from having an inadequate ballpark to the newest and, arguably, the best one available.

2. Milwaukee. Despite the manpower shortage of World War II, and having a really inadequate ballpark in Borchert Field (it was older than any major league park, and its dimensions were similar to those of the Polo Grounds), the minor-league version of the Milwaukee Brewers drew rather well.

The 1895 City Hall, as seen in

the opening of Laverne & Shirley.

The lettering was removed in 1988.

But Veeck and his Brewers proved that Milwaukee could support a major league team. So the County of Milwaukee began building a stadium, confident that they could get a team. By then, Veeck had owned the Cleveland Indians, and was owning the St. Louis Browns, and intended to move them to Milwaukee. There was also a group trying to buy the St. Louis Cardinals from Fred Saigh, who had to go to prison and sell the team due to tax fraud, and move them to Milwaukee.

So if the Braves hadn't exercised their option before the 1953 season, some Major League Baseball team would surely have been playing home games at Milwaukee County Stadium in April 1954. But the Braves, literally and figuratively, made their move. Gussie Busch bought the Cardinals, keeping them in St. Louis. Veeck tried to move the Browns to Baltimore, but MLB voted that the move could only go forward with another owner, so he sold them, and they became the Baltimore Orioles.

Milwaukee was a good market. The Braves ended up bringing in more fans in their 1st 13 home games in Milwaukee in 1953, 312,936, than they did in all 77 games in Boston in 1952, 281,281. In 1954, they set an NL record for highest attendance, and did it again in 1957. O'Malley got jealous of the attendance and the parking spaces, and the rest is history.

Downtown Milwaukee, circa 1957

Of course, something like this could have happened to the Red Sox, right? After all, their attendance and their stadium and parking situations weren't too hot, either.

But it wouldn't have happened to them, for one big reason -- also the biggest reason it was going to be the Braves that moved, not the Red Sox:

1. Tom Yawkey. Despite the Braves' 1948 Pennant, once Yawkey, a man whose lumber mill fortune gave him virtually bottomless pockets, bought the Red Sox in 1933, the Braves were doomed.

As soon as he turned 30, and was legally able to claim the fortune that had been left in a trust by his uncle, William Hoover Yawkey, Thomas Austin Yawkey sought to buy a baseball team. The 1st team he tried to buy was the Detroit Tigers, of whom his uncle had been a minority owner. He asked no less than the greatest Tiger of them all, Ty Cobb, to ask Tiger owners Frank Navin and Walter Briggs if they were interested in selling.

If they had sold the Tigers to Yawkey, baseball history might have been very different. Yawkey might still have benefited from Connie Mack's 2nd Philly fire sale in the 1930s, buying Lefty Grove, Jimmie Foxx and Al Simmons, and buying Joe Cronin from the Washington Senators, but they would have become Tigers instead. Joining with Hank Greenberg and the other stars the Tigers already had, in addition to their Pennants of 1934, '35, '40 and '45, they might have won additional Pennants (they probably only lost to the Yankees in '36 because Greenberg got hurt and missed most of the season), and more than just the 2 World Series in '35 and '45.

If the Tigers had won in '34, the legend of the Cardinals' Gashouse Gang would be diminished: Frankie Frisch and Dizzy Dean (not to mention the former Giant and Cardinal teammates that Frisch advocated for election once he got to the Veterans Committee) might not have made the Hall of Fame, and Leo Durocher probably never would have become a manager, thus altering the histories of the Dodgers, then the Giants, and finally the Cubs.

But the Red Sox wouldn't have regained their status as an AL power by the late 1930s, and wouldn't have been the Yankees' main challenger for AL supremacy from 1946 to 1951. They might have been the ones to move from Boston to Milwaukee -- with the Braves facilitating the move to the home of their top farm club.

Can you imagine Ted Williams returning from Korea and playing in Milwaukee? He might have been happier, with both a fan base and a media establishment that didn't know him before he got so big, and only knew him as an already-legendary figure, and would have given him the benefit of the doubt, which Boston's fans and papers weren't doing at the time.

Can you imagine Hank Aaron playing in Boston, becoming a beloved black baseball player there before the Red Sox integrated (1959 -- the Braves did it in 1948), and long before the Sox had a genuine black star in Jim Rice in 1975? Can you imagine the Boston fans coming out to support Hank, including those tweedy literary types who made up the old stereotype of the Red Sox fan, as he approached 714 career home runs? Can you imagine that kind of support, which he didn't get in Atlanta? (The Braves sold out the last game of 1973 and the 1st of 1974, but that was about it.) Hank might have broken the record in late '73 instead of the '74 home opener, and saved himself an offseason of anticipation and aggravation.

But when Cobb talked to Navin and Briggs, he found out that they weren't interested in selling the Tigers. But they did tell him that they heard that the Red Sox might be for sale. Cobb told Yawkey, and Yawkey bought the Red Sox. From the moment he and his bank account set up shop at Fenway Park, the Braves' fate was sealed.

How Yawkey ran the Red Sox, and the extent of his culpability for their failure to win a World Series from 1933 until his widow died in 1992, and the extent of his culpability for their lack of racial integration until 1959, is a separate debate.

VERDICT: Not Guilty. The argument for the Braves staying in Boston, that they had great young players coming up, and that these players would drive up attendance, was only a guess in 1953. And even if they did stay then, there's no way to know that they would have been able to drive Yawkey out before 1967, when the Sox became profitable and a New England icon in a way they hadn't been since 1949, and weren't in 1952.

The Braves had to go. And it worked out. For a while. Why did they have to leave Milwaukee after only 13 seasons? That's a blog post for another time.

No comments:

Post a Comment