Like the little girl with the curl in the middle of her forehead, when the Pittsburgh Pirates have been good, they've been very, very good; but when they've been bad, they've been horrid.

Finally, last year, after 21 years without a winning season, never mind a Playoff berth, they saw the far side of Game 162 again. Whether this is the beginning of another very, very good era of Bucco Baseball remains to be seen, but it's a good sign, as Pittsburgh is a great sports city, and Western Pennsylvania a great sports region.

5. Pittsburgh's All-Time Baseball Team

All of these players are from Pennsylvania, west of the Susquehanna River. Players from northern West Virginia were eligible, but I decided only one would make the team, and then only as an Honorable Mention -- although Bill Mazeroski, the legendary Pirates 2nd baseman, was born in Wheeling but grew up in southeastern Ohio, and I put him on the Cleveland Indians' regional all-time team.

1B James "Ripper" Collins of Altoona. A rookie with the St. Louis Cardinals when they won the 1931 World Series, he led the National League in games, home runs, total bases and slugging in their 1934 World Championship "Gashouse Gang" season. He appeared in 3 All-Star Games and 3 World Series, also going to the 1938 edition with the Chicago Cubs. He only played 8 full seasons (debuting at 27 and only playing one after 34), but was a .296 lifetime hitter, OPS+ 126.

2B Jacob Nelson "Nellie" Fox of St. Thomas. After the 1949 season, when he'd played a grand total of 98 games, the Philadelphia Athletics traded him to the Chicago White Sox for Joe Tipton. (Who?) A backup catcher and a .236 lifetime hitter, that's who. We'll never know if Nellie could have helped the A's enough to keep them in Philly. We do know he gave the South Siders 14 good seasons, 12 of them All-Star seasons, before wrapping it up with the Houston Astros.

He led the American League in hits 4 times. Had 6 .300 seasons and just missed 2 others. He struck out just 216 times in 19 big-league seasons. He won 3 of the 1st 4 Gold Gloves awarded to AL 2nd basemen. With Chico Carrasquel, he formed a very good double-play combination; then, with Luis Aparicio, he formed one of the best ever, now immortalized in a pair of statues at U.S. Cellular Field.

In 1959, he hit only 2 home runs, but batted .306, drove in 70, collected 191 hits including 34 doubles, and fielded brilliantly, helping the White Sox win their only Pennant between 1919 and 2005, and winning the AL's Most Valuable Player award.

He died in 1975 of skin cancer, when he was just short of his 48th birthday, and did not reach the Hall of Fame until well after his death, but is now there. The White Sox have retired his Number 2. Writer, radio host and humorist Jean Shepherd, best known for writing the book that became the film A Christmas Story, which he narrated, was a die-hard White Sox fan, and narrated the team's official history videotape in 1987, saying that Fox was his favorite ballplayer of all time.

SS Honus Wagner of Carnegie. He debuted in the opening months of the William McKinley Administation (July 17, 1897), played his last game during World War I (September 17, 1917), and died in the infancy of rock and roll (December 6, 1955), but he is still the greatest shortstop who ever lived (ahead of Derek Jeter), and for decades he was a legitimate contender for the title of Greatest Ballplayer Who Ever Lived.

John Peter Wagner was called Hans, the German version of John, and this became "Honus." Despite being bowlegged, he had enough speed that he was called the Flying Dutchman. ("Dutch" meaning "Deutsch," meaning German -- not as in "from the Netherlands." The word "Dutch" originally meant all peoples speaking a Germanic language, as Dutch is.) He debuted with the Louisville Colonels, but they were among the teams contracted by the National League in the 1899-1900 off-season, and their players went to the Pirates -- fortunately for Wagner, his hometown team.

And he was off to the races. He won 8 batting titles, 1st among NLers and 2nd overall to Ty Cobb, peaking at .381 in 1900. Twice, he led the NL in hits. This was the Dead Ball Era, and the most home runs he ever hit in a season was 10, but 7 times he led in doubles, twice reaching 45; 3 times he led in triples, topping out at 22. He had 9 100+ RBI seasons, topping out at 126, and 5 times led the NL. And 5 times he led the NL in stolen bases, topping out at 61. He was also regarded, by the standards of the time, as a great fielder, and appeared at every position except catcher -- even making 2 pitching appearances, tossing 8 1/3 innings without allowing a run.

His lifetime batting average was .328, his OPS+ 151. He collected 3,420 hits, a record until surpassed by Cobb (still 7th all-time, and 2nd to Hank Aaron among righthanders), 643 of them doubles (9th all-time), 252 of them triples (3rd all-time to Sam Crawford and Cobb), 101 of them home runs. He helped the Pirates win Pennants in 1901, '02 and '03, and in 1909 led them to their 1st World Series win, beating Cobb and the Tigers in 7 games, the first Series to go the distance.

He was a charter inductee into the Hall of Fame in 1936. In 1999, 82 years after he played his last game, he was voted onto the All-Century Team, and The Sporting News named him Number 13 on their list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players. A coach with the Pirates after he retired, he stayed long enough for uniform numbers to be worn, and they retired his Number 33.

He lived long enough to see the Pirates dedicate a statue of him outside Forbes Field in 1954; it was moved to Three Rivers Stadium in 1970 and PNC Park in 2001. His brother Albert "Butts" Wagner also played in the majors, but only for 74 games in 1898.

If there's one thing most fans know about Honus Wagner, it's that he appeared on the most valuable baseball card ever printed. Before chewing gum companies produced cards, tobacco companies did, and in 1909, the American Tobacco Company produced what became known as the T206 series. Wagner asked them to stop production of the card, because he didn't want children buying cigarettes in order to get it. According to The Book of Lists, published in 1977, only 96 copies of the card were ever made, and 30 were then known to exist. Even then, the Wagner T206 was the most valuable card ever produced, and in 2011, one sold at auction for $2.8 million.

Honorable Mention to Bobby Wallace of Pittsburgh. He reached the majors in 1894 (in the 2nd Grover Cleveland Administration) and played until 1918. How long ago was that? So long ago that he played for a Cleveland team in the National League (the Spiders) and a St. Louis team in the American League (the Browns).

He was a great fielder by the standards of his time, and hit .300 and drove in 100 runs twice each. He collected 2,309, hits including 391 doubles and 143 triples. He wasn't a bad pitcher, either. In fact, of all players in the Hall of Fame who played at least half their careers in the 20th Century, he made more mound appearances than anybody not usually thought of as a pitcher except Babe Ruth, 57.

He went 12-14 for the 1895 Spiders (with Cy Young also in the rotation, and they beat the original Baltimore Orioles in a postseason series for the Temple Cup – more an equivalent to English soccer's FA Cup than any "world championship") and 10-7 for the 1896 edition (which played the Orioles in the Temple Cup again, but lost). He's in the Hall of Fame.

Honorable Mention to Dick Groat of Swissvale. Perhaps the 1st great basketball player at Duke University, he chose baseball instead, and was 4 times an All-Star for his hometown Pirates. In 1960, he led the NL in batting with a .325 average, won the MVP, and took the Pirates to the World Championship. Traded to the Cardinals in 1963, he nearly won another MVP, finishing 2nd to Sandy Koufax as he led the NL with 43 doubles, before helping them win the World Series in 1964 – both his rings coming against the Yankees.

He had 2,138 hits in just 14 seasons, missing some time due to Korean War service, and retired at 36. Had he not had to serve in the Army, he might have put up another good season or two, and we’d be thinking about him for the Hall of Fame.

3B Dick Allen of Wampum. Don't call him "Richie," although most references to the 1964 Phillies still list him as such. He was named NL Rookie of the Year that season, leading the League in runs, triples and total bases, batting .318 with 29 homers and 91 RBIs. A 7-time All-Star, he was as good a hitter as the game has ever seen from the time he was 22 until he was 32, 1964 to 1974.

Chased out of Philadelphia in 1969, he got to the Chicago White Sox in 1972 (and playing mostly 1st base from 1969 onward), and that year won the AL MVP, leading in home runs with 37, RBI with 113, OBP with .420, slugging with .603 and OPS with 1.023, batting .308. Lots of people in Chicago, noting that the ChiSox had been struggling financially and had come closing to moving once already, say that the crowds coming to see Allen's drives (he also led the AL in homers in 1974) saved the franchise from being moved.

He had a lifetime batting average .292, on-base percentage .378, slugging percentage a hefty .534, OPS .912, OPS+ 156. This guy should have gone to the Hall of Fame.

So what happened? The Phils went on a 10-game losing streak and just missed the Pennant in 1964, although Allen hit like hell that month, so you can't blame him. The next year, he got into a fight with teammate Frank Thomas (not to be confused with the later White Sox slugger), which was apparently racially motivated. Management took the side of the better-hitting Allen, and traded Thomas.

But Philly's white fans didn't forgive him for that, and booed him terribly until he finally got his wish to be traded. He began to be paranoid about racial matters, drank heavily, gambled a lot on horse racing, and frequently showed up late for games. He ended up quitting on the White Sox in 1974, and managed to get back with the Phillies, whose fans, no longer in the black neighborhood that Connie Mack Stadium was in, cheered him vociferously at Veterans Stadium.

But despite reaching the postseason in '76, his demons remained, and a year later he was out of baseball. He hit "only" 351 home runs, despite playing his entire career in pitchers' parks (Connie Mack Stadium, a year at Busch Stadium in St. Louis, a year at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, Comiskey Park, the Vet, and his last year at the Oakland Coliseum) and having his last productive season at age 34.

Allen took his passion for racehorses in a positive direction, training them, and returned to the Phillies in a front-office capacity, and remains with them today. Some people believe he should be in the Hall. Many have squelched the notion that he was underachieving and divisive, including Hall-of-Fame teammates Goose Gossage and Mike Schmidt, and former managers Red Schoendienst, Chuck Tanner and, shortly before his death, Gene Mauch.

Both the Philadelphia Baseball Wall of Fame (at Citizens Bank Park) and the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame (at Hawthorne Race Course -- appropriate, at least in his case) have inducted him.

Honorable Mention to Eddie Miller of Pittsburgh. It's hard to tell why this Boston Brave and Cincinnati Red appeared in 6 All-Star Games. Either he must have been a good fielder, or in the years between Pie Traynor and Eddie Matthews, the NL must’ve been hard-up for good 3rd basemen, so they took this guy with an 80 career OPS+ and a peak batting average of .276. Still, he led the NL with 38 doubles in 1947.

LF Stan Musial of Donora. Once, at a Hall of Fame induction weekend, Stan, the greatest National League hitter of his generation, was talking with his American League counterpart, Ted Williams. Afterwards, Ted’s son, John Henry Williams, asked his father, who was known for wanting people to call him the greatest hitter who ever lived, "Dad, do you think Musial was as good a hitter as you were?" Ted said, "Yes, I do." If Ted said it, then, indeed, Stan was The Man.

In his 1st 4 full seasons with the St. Louis Cardinals – minus 1941, when he had a late-season callup and the Cards just missed, and 1945 when he was in the Navy for World War II – they won the World Series in 1942, the Pennant in 1943, the World Series in 1944, and the World Series in 1946. They never won another Pennant with him, but that didn't stop him. He was the NL MVP in 1943, 1946 and 1948, and finished 2nd in the voting in '49, '50, '51 and '57 – winning Sports Illustrated's Sportsman of the Year award that year.

His lifetime batting average was .331, and when someone asked him after he retired why he was so happy all the time, he said, "If you had a .331 lifetime batting average, you'd be happy, too!" His OPS+ was a whopping 159. He led the league in batting 6 times (topping out at .376 in 1948), hits 6 times, runs 5 times, doubles 8 times, triples 5 times, and RBIs twice with 10 100-RBI seasons.

He hit 725 doubles (2nd all-time to Tris Speaker) 177 triples, and 475 home runs, not counting what we would now call a walkoff homer in the 1955 All-Star Game. Speaking of which, because of the 2 ASGs played per season from 1958 to 1962, he played in 24, a record that would be tied by Willie Mays and Hank Aaron, but not broken. At the 1962 ASG in Washington, when he was 41, the 45-year-old President John F. Kennedy told him, "They said I was too young to be President and you were too old to play baseball. I guess we showed them."

He was once the NL's all-time hits leader with 3,630 – 1,815 at home, 1,815 on the road. You cannot make this stuff up. He was once the all-time leader in both extra-base hits and total bases, until surpassed by Aaron. He is a member of the Hall of Fame and the All-Century Team. The TSN100 ranked him Number 10.

His Number 6 was the 1st uniform number retired in St. Louis sports, and a statue of him dedicated outside Busch Stadium, inscribed with a quote attributed to former Commissioner Ford Frick: "Here stands baseball's perfect warrior. Here stands baseball's perfect knight." It has been moved to the new Busch Stadium.

Honorable Mention to Jesse Burkett of Wheeling, West Virginia. Only 5-foot-8 and 155 pounds, he nonetheless had a lifetime batting average of .338, an OPS+ of 140, and 2,850 hits. He won 3 batting titles, in 1895 (.405) and 1896 (.410) with the NL's Cleveland Spiders, and in 1901 (.376) with the Cardinals, before moving on to the St. Louis Browns of the AL. (Cleveland in the NL? St. Louis in the AL? As I said earlier, it was a long time ago.) He's the only West Virginia product in the Hall of Fame. (Bill Mazeroski and George Brett were born there, but grew up elsewhere.)

Honorable Mention to Hank Sauer of Pittsburgh. In 1952, he won the NL's MVP despite playing for a Cub team that finished 5th, as he led the League in homers with 37 and RBIs with 121. He was so popular with Cub fans that he became known as the Mayor of Wrigley Field, before Ernie Banks arrived and well before Harry Caray did. He had a career OPS+ of 123, and hit 288 home runs.

Honorable Mention to John Preston "Pete" Hill of Pittsburgh. Born in Culpeper County, Virginia, he grew up in the Steel City, and played for several all-black teams from 1899 to 1925, playing the longest with the Chicago American Giants, whose owner, manager and ace pitcher Rube Foster called him "my field general" and "my second manager."

He played against what could hardly be called entirely big-league caliber competition, and with records woefully incomplete, but Cumberland "Cum" Posey, owner of the Homestead Grays, said that Hill was "the most consistent hitter of his time." When in 2006 the Hall of Fame had a special committee consider Negro League players that they might have missed, Hill was one of those elected.

CF Lewis "Hack" Wilson of Ellwood City. He might be the most defensively lacking center fielder on any of these teams, but what can you do when Ken Griffey Jr. doesn't qualify? (Explanation for that below.) Besides, as his nickname might suggest, Hack might have been a more powerful hitter than Griffey. He was just 5-foot-6, and at 190 pounds it was suggested that he was "shaped like a beer barrel, and not unfamiliar with its contents." Despite playing all but his last season in the Prohibition era, few athletes were ever more identified with drunkenness.

And, due to his size, he wasn't the most mobile of outfielders. Legend has it that he was standing in the outfield at Baker Bowl in Philadelphia during batting practice before a Cubs-Phillies game, and he had his head down so he didn't have to aim his heavy, bloodshot eyes at the hot sun. But a teammate hit a ball off the park's close, tall right field wall. The sound of horsehide on tin shook him out of his stupor, and he grabbed the ball and threw a perfect strike back to the infield, and got a standing ovation – shades of the Dick Stuart hot-dog wrapper story.

But, when sober, boy, could he hit. In just 12 seasons, he hit 244 homers, with a batting average of .307 and an OPS+ of 144. He led the NL in homers 4 times, including 56 in 1930, a record that stood until 1998 (or 2006, if you think Ryan Howard is clean, as he so far appears to be). That same year, a year after driving in 159 runs, Hack had 191 RBIs, an all-time single-season record.

But the drinking took its toll, and he had just 1 season of more than 61 RBIs after that. He did help the New York Giants win the Pennant in 1924 and the Cubs do it in 1929. But, frustrated by his drinking, the Cubs traded him in 1932, and he did not play for that Pennant winner.

Drinking killed him in 1948, age 48. A sad story. But he is in the Hall of Fame, and is honored in the Cubs' Walk of Fame outside Wrigley Field, although he did not wear a number that could be retired for him until after he left the Cubs (Number 4).

RF Ken Griffey of Donora. While his son, George Kenneth Griffey Jr., was also born in Donora, he grew up in Cincinnati, and attended the prestigious Archbishop Moeller High School, as did MLB players Buddy Bell (son of former Reds star Gus Bell), Buddy's son David Bell, and Barry Larkin; and former Chicago Bear turned ESPN 1000 host Tom Waddle. Therefore, Junior qualifies for the Reds' regional team, not the Pirates'.

Ken Sr. was a pretty good player, too. In 19 seasons, he batted .296, with an OPS+ of 118, 2,143 hits including 364 doubles. He wasn't a big slugger, as he only topped 14 homers and 74 RBIs once each. But he was a 3-time All-Star, and helped the Reds win the 1975 and '76 World Series and the '79 NL West title, nearly helped get the Yankees to the 1985 AL East title, and finished his career in 1990 and '91 with his son on the Seattle Mariners.

UT John Montgomery Ward of Bellefonte. This pioneer of the game could play just about anywhere, including pitching. "Monte" had 3 .300+ seasons, and while stolen-base records were not kept from his 1878 debut (at age 18!) until 1886, he is credited with 540, including 111 in 1887. (The rules for what constituted a "stolen base," like a lot of rules, were a little different then.) He won NL Pennants with the Providence Grays in 1879, and the New York Giants in 1888 and 1889.

A practicing attorney in the off-season, he led the Players' League revolt of 1890, and almost freed the players' from the yoke of the owners' reserve clause. If he had just held out a little longer... But he did play long enough to get into the Hall of Fame.

C Josh Gibson of Pittsburgh. He never played in white "organized ball," so we don't have anything close to accurate numbers on him. If there's even any film of him playing that survives, I'm not aware of it. So all we have to go on are anecdotes. Indeed, no player in the history of the game may be more shrouded in legend, simply because, unlike Satchel Paige, whom we at least got to see in his later years, the evidence of Gibson's performance is sketchy at best.

I don't care: They call this man "the Black Babe Ruth," and that's good enough for me. Indeed, some Negro Leaguers called Ruth "the White Josh Gibson," which shows what kind of power Josh must have had.

He was born in Georgia, but grew up in Pittsburgh. He played most of his career for the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays, who divided their home games between Pittsburgh -- Homestead is nearby -- and Washington.

Two legends about him usually come to mind. Once, in Pittsburgh, he hit a ball so far that no one saw it come down; the next day, after riding the bus to Philadelphia, with the same umpire, a ball came out of the sky as they were warming up, and a player from the other team caught it, and the umpire turned to Gibson, and said, "You're out -- yesterday, in Pittsburgh!"

The other legend is that he was the only man who ever hit a fair ball all the way out of the old Yankee Stadium. Negro League pitcher Jack Marshall said Josh did it in 1934. Buck O'Neil said he heard the story from Buck Leonard, "And Buck don't lie." Well, Buck O'Neil must have lied, because Buck Leonard said he wasn't at the game where it supposedly happened. And Josh himself never claimed to have done it, a not-telling that is very telling: If you had done it, why wouldn't you talk about it?

A few years back, a sportswriter decided to look at the sources most likely to have said at the time that it happened: The major black newspapers, such as New York's Amsterdam News, the Baltimore Afro-American, the Pittsburgh Courier, the Chicago Defender and the Kansas City Call. While he found several references to Josh hitting home runs at Yankee Stadium, including some very long ones, at the level of Ruth and Mickey Mantle, he found no contemporary references to him hitting one all the way out. If those papers didn't say at the time that he did it, then that's as close as we're ever likely to come to settling it.

Josh Gibson died of a brain tumor in 1947, just 35 years old, only 3 months before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. He was elected to the Hall of Fame, and when The Sporting News announced its 100 Greatest Baseball Players in 1999, he came in at Number 18, the highest-ranking of the 5 players they chose from Negro League legend. In recognition of his performances in D.C. for the Grays, a statue of him stands at the center field gate of Nationals Park, alongside statues of Walter Johnson and Frank Howard.

SP George "Rube" Waddell of Bradford. In 1904, he struck out 349 batters, a single-season record in the majors until 1965 (Sandy Koufax) and in the AL until 1973 (Nolan Ryan) – although it was miscounted as 343 for many years, and Bob Feller was thought to have broken it with 346 in 1946. In 1905, he went 27-10 with a 1.48 ERA. He helped the Philadelphia Athletics win Pennants in 1902 and 1905, and nearly another in 1907.

But... I don't know if he was retarded, or had the worst case of attention-deficit disorder in baseball history, but he could never focus on anything, a situation he didn't make any easier by becoming an alcoholic. A's manager Connie Mack finally had enough, and in 1908 sold him to the Browns. By 1910, age 33, he was done. In 1914, age 37, he died of tuberculosis.

But he's in the Hall of Fame. His career record was 193-143, a 2.16 ERA, a 135 ERA+, and 2,316 strikeouts despite only 11 full seasons. If he'd played today, a team psychologist would probably have figured out what was wrong, and they might've known what to do. Instead, he pitched his last big-league game over 100 years ago, and nobody understood.

SP Eddie Plank of Gettysburg. Another stretch, although Gettysburg is further to the west than York. In fact, like York, it's closer to Baltimore and Washington than it is to Philadelphia – and now you know why Robert E. Lee wanted it so badly in 1863, and why the Union defended it fiercely enough to beat the Confederates back across the Mason-Dixon Line.

Plank was Waddell's teammate from 1902 to 1907, and, fortunately, Connie Mack had a much easier time with this great lefthander. He helped the A's win Pennants in 1902, 1905, 1910, 1911, 1912, 1913 and 1914, winning the World Series in 1910, 1911 and 1913. His record was 326-194, winning 26 twice, 24 on 2 other occasions and 23 on 2 others. Career ERA 2.35, ERA+ of 122.

A's teammate Eddie Collins said, "Plank was not the fastest, not the trickiest and not the possessor of the most stuff, but he was just the greatest." He's in the Hall of Fame. When The Sporting News announced its 100 Greatest Baseball Players in 1999, he came in at Number 68.

SP Bob Purkey of Pittsburgh. The graduate of South Hills H.S. both began (1954-57) and ended (1966) his career with his hometown Pirates, but he's best-remembered with the Cincinnati Reds, helping them to win the Pennant in 1961 with a 16-12 record. He was even better in 1962, going 23-5. He won 129 games in his career, and is a member of the Reds' Hall of Fame.

SP Gary Peters of Mercer. He pitched only 2 games as a rookie for the Pennant-winning "Go-Go White Sox" of 1959, and didn't stick in the majors until 1963, when he was already 26. But what a way to stick that season: He went 19-8, had a League-leading 2.33 ERA, and was named AL Rookie of the Year. In 1964, he was even better, 20-8, as the Sox finished just 1 game behind the Yankees.

He led the AL in ERA again in 1966 with 1.98, and in 1967 went 16-11 with 2.28 as the Sox came close again, finishing 3 games behind Boston. He probably would have won more had he pitched for, say, the White Sox of 1917-19, or the 1977 "South Side Hit Men," or the Frank Thomas teams of the 1990s, but he still won 124 games.

SP Sam McDowell of Pittsburgh. Probably the best left arm ever to come out of the city's Central Catholic H.S. – with Dan Marino having the school's best right arm. In 1965, "Sudden Sam" went 17-11 for a weak Indians team, and led the AL in ERA with 2.18 and strikeouts with 325 – and he was only 22 years old. He led the AL in strikeouts 5 times, and went 20-12 for an even weaker Tribe in 1970.

But he was wild, on and off the field. He led the AL in walks 5 times and wild pitches 3, and his drinking got out of control. In 1972, the Indians traded him to the San Francisco Giants for Gaylord Perry. This was a rare great trade by the Indians, as Perry won the AL Cy Young Award; while, at 29, McDowell was basically through, going just 19-25 away from Cleveland after going 122-109 with them.

Still, he did pitch in 6 All-Star Games, win 141 games, struck out a substantial 2,453 batters despite having only 10 full seasons, and his ERA+ was 112. The Indians have honored him in Heritage Park at Progressive Field. Having gone through treatment, he is now a substance abuse counselor and a sports psychologist. In that latter role, he worked with the Toronto Blue Jays, and was awarded a World Series ring in 1993.

An urban legend has it that the Cheers character Sam Malone, played by Ted Danson was based on McDowell, although "Mayday" was righthanded, and actually assisted other people's drinking by running a bar. (The photograph of a Red Sox pitcher hanging at the bar is actually of 1967 hero Jim Lonborg, hence, anytime Sam had to be shown wearing a uniform, it was Lonborg's Number 16.)

RP Albert "Sparky" Lyle of DuBois. He was a rookie on the Pennant-winning "Impossible Dream" Red Sox of 1967, but the team's management didn't understand him. He was the stereotypical flaky lefthander – or, if you prefer, the stereotypical flaky reliever. So, after the 1971 season, they traded him to the Yankees for Danny Cater and Mario Guerrero. Cater was the key: He always hit well in Fenway Park, so why not play him at Fenway 81 times a year? Big mistake: Cater and Guerrero did nothing for Boston.

Sparky in The Bronx? He set an AL record (which lasted all of one year) with 35 saves in 1972. He was a major force in the Yanks' return to glory, winning the Pennant in 1976 and the World Series in 1977, a season in which he became the 1st reliever to win the AL Cy Young Award. The Yanks had had good relievers before (see below), but Sparky kicked it up to a new level, which would one day be reached and surpassed by Dave Righetti and Mariano Rivera.

Unfortunately for Sparky, that level would first be reached by Rich "Goose" Gossage, and, in just 1 year, according to teammate Graig Nettles, "Sparky went from Cy Young to Sayanora." His tell-all book, The Bronx Zoo, became a best-seller, and he ended up getting another ring with the 1980 Philadelphia Phillies. In fact, as far as I can tell, he's the only man ever to win Pennants with the Yankees, Phillies and Red Sox.

He saved 238 games in his career, 141 for the Yankees. His ERA+ is 128. He hasn't yet received a plaque in Yankee Stadium's Monument Park, and his Number 28 has been kept in circulation (currently worn by manager Joe Girardi, to signify the goal of a 28th World Championship). But he has been the subject of a YES Network Yankeeography.

From 1998 to 2012, Sparky was the manager of the Bridgewater, New Jersey-based Somerset Patriots, whose 5 Pennants have made them the most successful team in Atlantic League history. Sparky's trademark bushy mustache led to the design of the Pats' mascot, a large schnauzer named Sparkee.

Honorable Mention to Joe Page of Cherry Valley. He really only had 2 effective seasons, but those were 1947 (14-8 with 17 saves) and 1949 (13-8 with 27 saves, a record at the time), and both times the Yankees won the World Series. In the latter year, when the Yanks and Red Sox went down to the wire, the key was that the Yankees had Page in their bullpen, and the Red Sox didn’t.

He was the 1st reliever to be known as a "Fireman," because he "put out fires." He mopped up for Allie Reynolds so much that a joke circulated among New York baseball fans. Q: Who’s pitching for the Yankees today? A: Reynolds and Page. And when Joe DiMaggio was asked about whether he was excited about his upcoming marriage to Marilyn Monroe, he supposedly said, "It's got to be better than rooming with Joe Page."

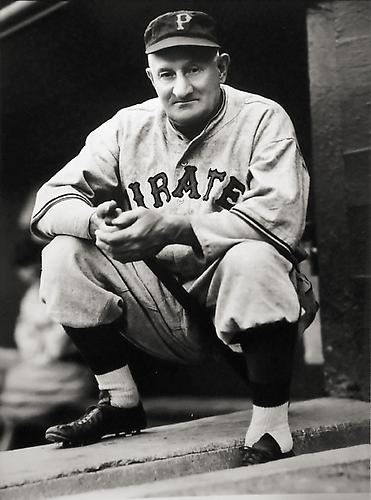

MGR Bill McKechnie of Wilkinsburg. The manager of the only New Jersey-based MLB team ever, the 1915 Newark Peppers of the Federal League (they finished 5th), "the Deacon" managed the Pirates to the 1925 World Championship, the Cardinals to the 1928 NL Pennant, and the Reds to the 1939 NL Pennant and the 1940 World Championship. He is in the Hall of Fame.

Tuesday, April 1, 2014

Pittsburgh's All-Time Baseball Team

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

Uncle Mike do you know any cool sports bar in Toronto to catch the Yankee game with some fellow Yankee fans?

Sorry, I checked. I'm not sure there's any cool sports bars in Toronto period.

If you're a soccer fan, the Duke of Gloucester Pub might be up your alley.

Post a Comment