Alexander Sherman -- who became "Allie" instead of "Alex," or even "Sander," as Michigan Congressman Sander Levin did -- was born on February 10, 1923 in Brooklyn, the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants. He attended Boys High School, in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section, before its merger to become Boys & Girls High School.

Other alumni of Boys High include: 2-time National League batting champion Tommy Davis; basketball stars Lenny Wilkens, Connie Hawkins, Si Green, Mel Davis; and sportswriter/sportscaster Howard Cosell. And that's just from the world of sports. It also produced novelist Norman Mailer, science fiction titan Isaac Asmiov, longtime Congressman Emanuel Celler, housing developer William Levitt, civil rights lawyer Will Maslow, his brother psychologist Abraham Maslow, painter Man Ray, music legends Aaron Copland and Max Roach, comedian Alan King, film producer Irving Thalberg, and actor Norman Lloyd, now 100 years old. Since the merger, its most notable graduate has been basketball star Dwayne "the Pearl" Washington.

When Sherman was 13, he was already a locally renowned athlete, and he tried out for the football team at Boys High. The head coach rejected him, for being too small. This was in 1936; Phil Rizzuto, even smaller, had already been the quarterback at Richmond Hill High School in Queens, before being rejected by Brooklyn Dodger manager Casey Stengel for being too small, and then signing with the Yankees where the rest was history -- although he would be reunited with Stengel, who admitted he was wrong, but Rizzuto never forgave him.

At 16, Sherman graduated, and got into Brooklyn College, paying his tuition with money he made from hustling older kids in handball. He tried out for their football team. This time, the coach wasn't the one who told him not to: His mother was. Allie and the coach talked her into letting him play, and in 1940 he became the starting quarterback. In 1942, he led BC to a shocking upset win over crosstown rival City College of New York (CCNY). He graduated at age 19.

There weren't many lefthanded quarterbacks in Sherman's day. But, knowing that Sherman had quarterbacked the T-formation, and that George Halas' Chicago Bears had shown that the T was the formation of the future and the single wing that of the past, Philadelphia Eagles coach Earl "Greasy" Neale took a chance on him. "Never have I seen a player with a greater understanding of the game," Neale said. "He was so dedicated, he insisted on rooming with a lineman. He wanted to absorb the way a lineman thought."

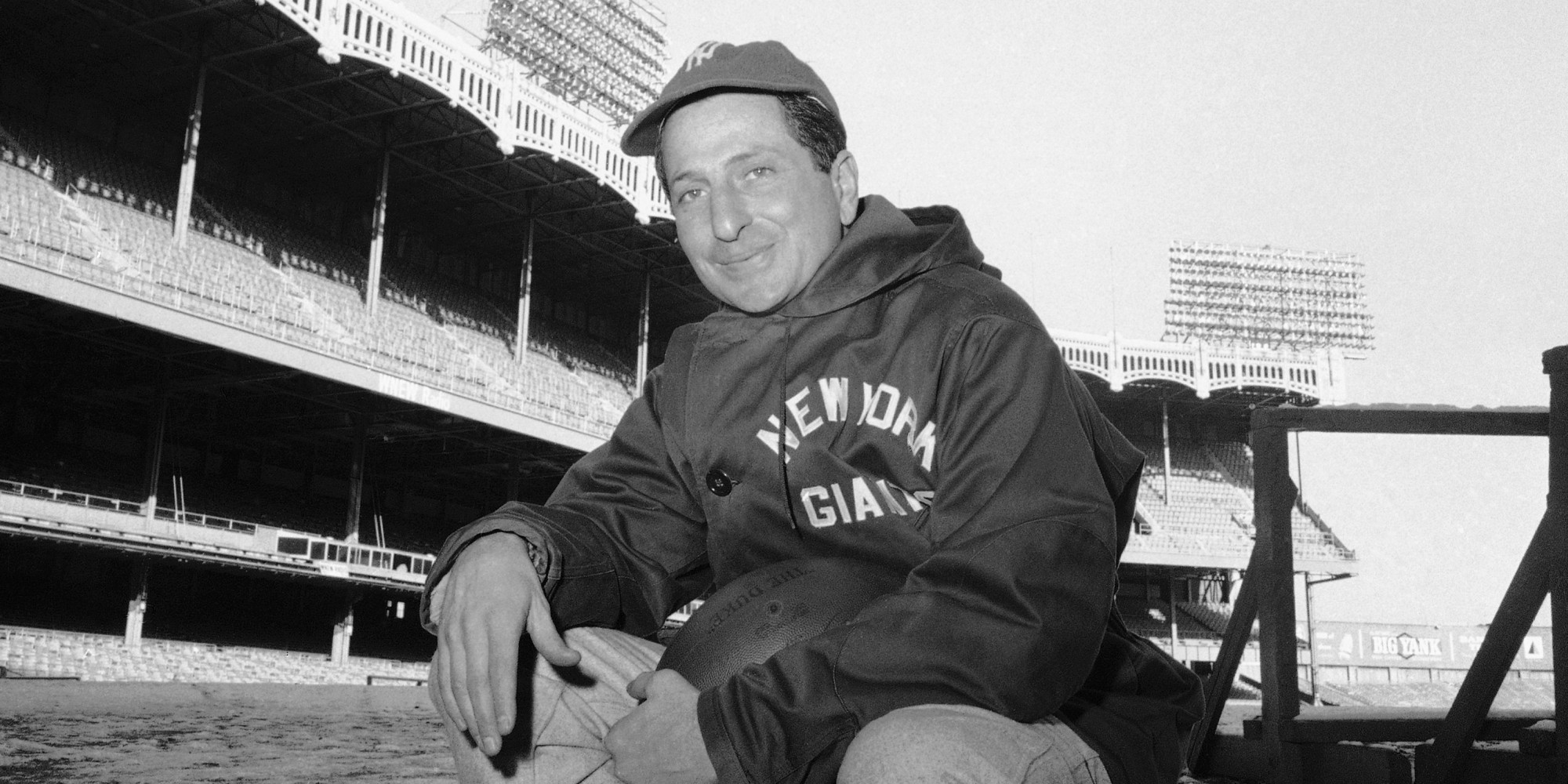

Eagles quarterback "Al" Sherman

Due to the World War II-induced manpower shortage, for the 1943 season, the NFL convinced the 2 Pennsylvania teams, the Eagles and the Pittsburgh Steelers, to merge for the season. The team, called the "Steagles," finished 3rd in the NFL Eastern Division with a record of 5–4–1. Both teams had started play in 1933, and this was the best finish that either of them had yet had.

The Eagles finished 2nd in 1944, '45 and '46, and tied the Steelers for 1st in '47. They beat the Steelers in a Playoff, the 1st postseason game in either team's history (and the only one the Steelers would play until the "Immaculate Reception" game in 1972). But they lost the NFL Championship Game to the Chicago Cardinals.

The next year, Neale put his faith in a new quarterback, Tommy Thompson. Sherman was gone -- but it worked, as the Eagles won the NFL Championship in 1948 (getting revenge on the Cardinals in a blizzard at Shibe Park) and 1949 (beating the Rams despite a rare Southern California rainstorm turning the Los Angeles Coliseum field into soup).

*

Sherman went into coaching. He won a title with a minor-league team in Paterson, New Jersey. Then Neale made it up to Sherman by recommending him to Steve Owen, longtime coach of the Giants. Owen had been losing due to his loyalty to the single wing, and finally gave up the ghost, and had Sherman teach the T to the Giants, turning Charlie Conerly into a championship and Hall of Fame quarterback.

When Owen retired after the 1953 season, Sherman didn't get the job -- former Giants player Jim Lee Howell did. It is worth nothing that Sherman was only 30 years old. There's no way any NFL team would name a 30-year-old man as head coach today. He did not, however, blame his rejection on his youth, or on his religion.

(UPDATE: The Los Angeles Rams hired Sean McVay as head coach in 2017, when he was only 31.)

He went to Canada, coached the Winnipeg Blue Bombers, and got them to the Playoffs. Canadian football's system, with 12 men on the field, 3 downs instead of 4, a wider field and deeper end zones, led Sherman to adapt with offensive schemes that would later help him in the NFL (even though he had to adapt back to the system he previously knew, as some of his Winnipeg plays, even with 11 men, wouldn't have been legal).

When the Giants took Sherman back as an assistant coach, the new Bombers head man was one of his receivers, Bud Grant, and he led them to 4 Grey Cup wins in 5 seasons, before moving on to the Minnesota Vikings, and leading them to 4 Super Bowls (though they lost them all).

In 1959, Giants offensive coordinator Vince Lombardi got the head job with the Green Bay Packers. He wanted Sherman to come with him as offensive coordinator. He refused, thinking Howell would soon move on, and that he would get the Giants job. This became more likely in 1960, as Giants defensive coordinator Tom Landry was named the 1st head coach of the expansion Dallas Cowboys. (Yes, kids: Lombardi and Landry were on the same coaching staff, in New York.)

In 1961, Howell left, and Sherman got his wish, at age 38, 8 years after he first hoped to. He wasn't the 1st Jewish head coach in the NFL, or even the Giants' 1st: Quarterback Benny Friedman was briefly a player-coach. But Sherman became the most successful Jewish head coach in NFL history.

With an aging but still effective Y.A. Tittle replacing Conerly, Sherman led the Giants to 3 straight Division titles. He earned NFL Coach of the Year awards in 1961 and 1962, the 1st time that a coach won that honor in back-to-back seasons.

But the Giants didn't win the title. In 1961, they got wiped out in the NFL Championship Game, losing 37-0 to the Green Bay Packers on a snowy New Year's Eve at what would later be renamed Lambeau Field.

In 1962, with Frank Gifford ending his 1-year retirement, they faced the Packers again, this time at Yankee Stadium. (In those days, the site rotated between the Division Champions, rather than getting assigned to whoever had the best record. Good thing for the Giants, as the Packers were 13-1 that year.) The cold, freezing the field, helped the Packers, but it shouldn't have fazed a team playing in New York, or a coach who had coached in Canada. But the renowned Giants defense, led by Sam Huff, couldn't stop Jim Taylor, and their offense couldn't get a footing, and the Packers won, 16-7.

The 1963 title game still stands as perhaps the most frustrating in Giants history. They played the Bears at a frigid Wrigley Field, and Tittle sustained a knee injury. Courageously, Tittle convinced Sherman to keep him in the game, and, despite repeatedly getting hit and driven into the frozen Wrigley grass, he led a final drive with the Bears up 14-10. But an interception ended the Giants' chances, and Tittle would never win a title.

In 1964, just as the Yankees would a year later, the Giants faced a situation where everyone seemed to get old, or hurt, or both, at once. The team collapsed from 11-3 to 2-10, its worst season ever, in just that 1 year, and Sherman no longer looked like a genius.

To make matters worse, Giants owner Wellington Mara orchestrated the trades of some of the better players: Huff went to the Washington Redskins, where he became a big part of that franchise's revival after a long down period; while defensive end Rosie Grier went to the Rams, where he became part of their imposing defensive line known as the Fearsome Foursome.

Sherman told Mara he should draft Joe Namath. He refused. Namath proved Sherman right, as he did become a great pro quarterback who led a New York team to a World Championship -- but it was the Jets. Instead of drafting the man who would become Broadway Joe, Mara traded for Vikings quarterback Fran Tarkenton, who never really meshed with New York or its fans, and was sent back to Minnesota, where he led them to 3 of their 4 NFC Championships.

The Giants got back to 7-7 in 1965, but in 1966, they crashed to their worst season ever, 1-12-1. In just 3 seasons, Sherman had coached the 2 worst seasons in Giant history. (They're still 2 of the 4 worst, for this franchise that has now played 90 seasons.) To the tune of "Good Night, Ladies," Giant fans began singing, "Goodbye, Allie."

This was long before the Jet fans' chant of "Joe Must Go" for Joe Walton, the Giant fans' chant of "Ray Must Go" for Ray Handley, or the Jet fans' chant of "FI-re KO-tite!" for Rich Kotite. Fans began bringing "GOODBYE ALLIE" banners. They did this at a time when Yankee management had banners confiscated at Yankee Stadium, thinking it was a bush-league thing that Met fans did. Sherman was unfazed, saying, "They paid their money, and can do what they want."

He may have won a few fans back by being savvy with the media, as he was among the earliest NFL head coaches to take press questions daily. Understanding NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle's desire to make the NFL more accessible to fans via television, every Monday morning after a game, Sherman presented game film clips and evaluations -- standard procedure now, but revolutionary at the time.

Rethinking his 1963 rejection of writer (and Giant fan) George Plimpton's idea to allow Plimpton to pose in training camp as a rookie quarterback (resulting in him going to the Detroit Lions and producing the bestseller Paper Lion, made into a movie with a young Alan Alda), in 1966 Sherman and Mara accepted the proposal of author Eliot Asinof (author of the Black Sox book Eight Men Out) to spend 2 years with the team having total freedom and unlimited access to players, coaches, and executives, even closed coaches meetings.

This resulted in a never-before seen behind-the-scenes look of the inner world of the professionals, Seven Days To Sunday, published in 1968. This was right before the publication of Packer guard Jerry Kramer's diary of the 1967 season, Instant Replay, and before Roy Blount Jr.'s insider's look at the 1972 Steelers, About Three Bricks Shy of a Load.

While college football coaches had previously had radio shows, Sherman produced and owned the 1st pro football coach's weekly television program, on then-independent station WPIX-Channel 11, reviewing film of the Giants' prior game and discussing football with invited players, coaches, and guests, giving many fans their 1st peek inside professional football and "up close and personal" moments with the players.

He co-produced and hosted a Monday night radio program, Ask Allie, airing on the Giants' station, WNEW (1130 on your AM dial, now Bloomberg Radio), where it was just him sitting in a booth, smoking a cigar, and directly taking fans call-in questions and comments.

The press respected Sherman for facing fans weekly, especially just 24 hours after a tough loss, and always treating them graciously. He also hosted the first nationally syndicated TV panel-discussion sports show called Pro Football Special, where, in reviewing touchdown plays, he would say that the runner, once in the clear, "goes in for the touch."

He annually held a big Christmas party for the press, inviting everyone who regularly covered the Giants, even his critics. All this won some of them over, but he was still sometimes called "very Madison Avenue-ish," suggesting that he should concentrate less on public relations and more on winning; less on "sizzle" and more on "steak."

In 1965 an 1966, he added former Giants Emlen Tunnell and Roosevelt Brown, both future Hall-of-Famers, to his coaching staff. They were the 1st 2 African-American assistant coaches in the NFL. This may have helped, strategically as well as with public relations: In 1967 and 1968, the Giants went 7-7, missing the newly-expanded Playoffs by 1 game in '68. It was a brief reprieve, and the crosstown Jets ended up beating the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III for the World Championship, the 1st for a New York football team since the 1956 Giants.

Then came the nail in Allie's coaching coffin: The following preseason, as part of the process of the AFL's absorption into the NFL, the 2 New York teams played each other for the 1st time -- not at Yankee Stadium or Shea, but at the Yale Bowl in New Haven. Three Jet players chose to come out of retirement, just for this 1 game, because they wanted to make a point about being not just the best team in the world, but the best team in New York. The Jets won, 34-17, and at the end of the season, Mara fired Sherman.

In his 1st 3 seasons as an NFL head coach, Sherman went 33-8-1. In his last 6 seasons, he went 30-51-3. Overall, he was 63-59-4. At age 46, he had coached his last game.

*

But he was neither away from the game nor unproductive with the 2nd half of his life. The main reason he didn't coach again in the NFL is that he thought it would be better to go into management, and so he turned down some offers. He tried to put together a group that would buy an NFL team. One of these attempts was with Steve Ross, head of Warner Communications, Inc. (WCI). They tried and failed to buy the Jets from Leon Hess.

Ross agreed with Sherman that sports content also had great potential value, with cable television as a delivery system. Ross asked Sherman to join WCI and use his coaching and media expertise to build good teams and develop these potential assets. While helping WCI win cable franchises in additional cities, Sherman was part of WCI's experimental QUBE system in Columbus, Ohio.

It was the nation's 1st interactive cable system, enabling QUBE customers to individually order film and other content direct from home on a pay-per-view basis. Sherman recognized its marketing and revenue potential for sports programming. He created cable's first sports subscription package with Ohio State University Chancellor Gordon Gee.

In each WCI cable system, in big cities like Dallas and Chicago, Sherman continued to acquire college and professional sports rights, and then built regional sports networks to exhibit the games and specially created related programming. Eventually they were all purchased, and are known today as the Fox Sports Networks. Sherman positioned WCI's growing cable systems as an integral part of the sales and marketing of national pay-per-view events, especially high-priced championship fights. He negotiated special rights deals with impresarios and friends Don King and Bob Arum.

Ross had been a founding co-owner of the North American Soccer League's New York Cosmos, and used WCI to boost the team and the league. When Pelé announced his retirement in 1977, he requested that the man he called "Allie Boss" produce his farewell game, a testimonial at Giants Stadium, between the Cosmos and Pelé's former club team in Brazil, Santos. Pelé would play a half for each team.

Sherman put together a package of an ABC special game presentation, a worldwide syndicate of TV networks in 117 countries, including the Soviet Union, global sponsors to market it, had Frank Gifford as host with myriad celebrities and officials, ending with a special award presented by Muhammad Ali, then still Heavyweight Champion of the World. (Supposedly, the man who liked to call himself "The Greatest" said of Pelé, "Now I understand: He is greater than I am.")

Between Pelé, Ali, the Cosmos, the power of New York, the love of the game, Ross' media reach, and Sherman's promotional genius, this broadcast remains, outside of World Cup matches, the most-watched soccer event ever broadcast.

Sherman was a frequent guest on Warner Wolf's late-Sunday-night sports wrap-up show on WCBS-Channel 2, and this led to him going up to Bristol, Connecticut to appear live on the early ESPN, making him famous beyond the New York Tri-State Area. Having worked with the father-son team of Ed and Steve Sabol to help establish NFL Films in the 1960s, giving their film crews full access to the Giants behind the scenes, Allie worked with Steve to produce ESPN's pregame show for Monday Night Football (now on ESPN but then still on ABC), Monday Night Matchup.

He and his co-hosts would break down the teams into key matchups, and use stop-action film and graphics to analyze the upcoming game. This format later became a standard feature in ESPN's and the networks' sports programming. One of his panelists was a fellow former Eagle quarterback, Ron Jaworski, giving the Polish Rifle (that was his nickname before every ESPN viewer knew him as "Jaws") the springboard to a media career that, as with Sherman, has now outshone his playing days.

In 1994, using his usual lack of tact (which pissed off many, but endeared him to many more, much like predecessor Ed Koch), new Mayor Rudy Giuliani wanted to reform New York's Off-Track Betting system for taking horse racing bets outside the racetracks. He said, "OTB is the only bookie in the world that loses money every year," and asked Sherman to run it.

As Giuliani did with the streets of New York, Sherman cleaned OTB up both figuratively and literally: He closed down run-down stores, fixed up the rest, and leaned on his Warner Cable connections to create a racing station and to allow Warner customers to phone in bets. In just 2 years, OTB was making a profit for the first time. (After he left, it fell into losses again, and The City shut it down in 2010.)

Throughout the years, Sherman was involved with many charities, including charities for children with special needs, the Boys and Girls Clubs of America, and the Veteran's Bedside Network, where he regularly visited veterans’ hospitals, to talk football and sports with disabled veterans.

This is the most usable (relatively) recent photo I could find of Allie, from the NFL's "Helping Hands Award" charity dinner in 2002. He's on the left. In the middle is Tony Veteri, an official in the AFL and NFL for 23 years. On the right is George Beim, Events Coordinator for the charity.

Allie Sherman died this past Saturday, a few weeks short of his 92nd birthday. He is survived by his wife Joan, son Randy, daughters Lori Sherman and Robin Klausner, and 2 grandchildren. He is a member of the National Jewish Sport Hall of Fame in Long Island, and the Brooklyn College Hall of Fame as well.

He wasn't a great player or a great coach, but he was good at both. His true brilliance was in bringing football to the people, making him as important a football-in-media figure as Rozelle, the Sabols, and ABC Sports boss and Monday Night Football founder Roone Arledge. The Pro Football Hall of Fame's media award is named for Rozelle. Allie Sherman should have gotten it years ago. Hopefully, with a new Hall of Fame election coming up this month, he will be recognized.

Note: Some of this text is taken from Wikipedia's entry on Sherman.

UPDATE: He was buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Hawthorne, Westchester County, New York, the same cemetery as another New York sports media legend, Bill Mazer. It is near Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, where Babe Ruth is buried; and that is next-door, albeit in an adjacent town, to Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, where Lou Gehrig is buried.

No comments:

Post a Comment