Up until the 1920s, it was rare when a man from the Pacific Coast made it to the major leagues -- or, as Pacific Coast League fans called them until 1958, "the Eastern leagues." Frank Chance was a notable exception.

But in the 1920s, big league clubs followed the advice incorrectly ascribed to 19th Century newspaper baron Horace Greeley: "Go west, young man, and grow up with the country." The San Francisco Bay Area, the Los Angeles area, San Diego, Portland and Seattle all produced plenty of good ballplayers in the next few years, and some of the Bay Area boys are listed here.

14. San Francisco's All-Time Baseball Team

This could well be the best of the 30. They are absolutely loaded in the infield. They have devastating bats and fantastic gloves in the outfield. And the pitching is pretty good, too. Put it this way: Bobby Jones was an All-Star, and he doesn't make this team. Then again, he's not even the best righthanded Met pitcher from Fresno.

1B Frank Chance of Fresno. Despite his association with shortstop Joe Tinker and 2nd baseman Johnny Evers, both borderline Hall-of-Famers at best and likely in only because of the Franklin P. Adams poem commemorating them, he had a .296 lifetime batting average, a 135 OPS+, led the National League in stolen bases in 1903, led the NL in on-base percentage in 1905, and led it in steals and runs scored in 1906.

"The Peerless Leader" is also the manager of this team, having led the Cubs to the 1906, 1907, 1908 and 1910 NL Pennants and the 1907 and 1908 World Championships – the only World Series the Cubs have ever won.

Honorable Mention to George "High Pockets" Kelly of San Francisco. A real borderline HOFer, probably in only due to the efforts of his New York Giants teammate, Frankie Frisch, who spent a long time on the Hall's Veterans Committee and got a bunch of his teammates in, worthy and otherwise.

But Kelly was no slouch: He had a .297 lifetime batting average, was 7 times a .300 hitter, 337 doubles, 5 100-RBI seasons and just missed a 6th, and led the NL in homers with 23 in 1921. He helped the Giants win the 1921 and '22 World Series, and also the '23 and '24 Pennants. He helped start a Series-ending double play against the Yankees in 1921 – from 1st base.

Honorable Mention to Dolph Camilli of Atherton, in San Mateo County, on the Peninsula between San Francisco and San Jose. He became a star with the Philadelphia Phillies, and in 1938 Larry MacPhail made him one of the guys who restored the Brooklyn Dodgers. He had a lifetime OPS+ 136, and hit 239 homers. In 1941, he led the NL in homers with 34 and RBIs with 120, leading the Dodgers to their first Pennant in 21 years and earning himself the MVP. But he never regained his batting stroke after returning from World War II.

Honorable Mention to Dick Stuart of Redwood City, also in San Mateo County. He once hit 66 home runs in a minor-league season. That was probably the worst thing that could have happened to him, as, afterward, people expected him to hit enormous amounts of home runs. In 1960, winning the World Series with the Pittsburgh Pirates, he hit 23 with 83 RBIs. The next season, he hit 35 with 117 RBIs. But he struck out way too much, and as for his defense, well, he was a liability.

He got traded to the Boston Red Sox, where his righthanded swing was perfect for Fenway Park, and he hit 42 homers in 1963, leading the American League with 118 RBIs, and 33 in 1964. But his defense was still so bad, they nicknamed him Stonefingers. Then, in '64, when the movie Dr. Strangelove came out, they started calling him Dr. Strangeglove. Supposedly, the Fenway wind blew a hot-dog wrapper onto the field, and he made a diving catch of it, and got a sarcastic standing ovation.

He moved on to the Phillies in 1965, and hit 28 homers, but that was his last full season, at age 32. He never made it to the DH era. His final total was 228 home runs, and he had an OPS+ of 117, but only a .264 batting average, and he struck out 957 times in the equivalent of 8 full seasons. A good guy, but too one-dimensional for the pre-1973 era.

Honorable Mention to Jim Gentile of San Francisco. A graduate of Sacred Heart Cathedral H.S., he edged Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris for the AL RBI title with 141 in 1961, and his 46 homers were the most in the majors that season by anyone other than the M&M Boys. It was his 2nd of 3 All-Star seasons for the Baltimore Orioles, but injuries left him unable to play in the majors beyond age 32. A 136 OPS+, but just 179 homers. He deserved better.

Honorable Mention to Bill Buckner of Napa. He played in 4 different decades (starting in 1969 and ending in 1990), 7 times (almost 8) batted .300, collected 2,715 hits, and appeared in 2 World Series. One of these, of course, was in 1986, but he hit 18 home runs and drove in 102 runs that season. Yes, it was in Fenway Park, but he was a lefty, not hitting over the Green Monster. The Boston Red Sox would not have won the Pennant if not for him.

Honorable Mention to Keith Hernandez of San Bruno, San Mateo County. Sorry, Mex, but until you're in the Hall of Fame, you're not ahead of High Pockets Kelly, let alone Frank Chance.

He shared the 1979 NL Most Valuable Player award with Willie Stargell (the only tied vote either League's MVP has ever had), leading the NL in batting with .344, doubles with 48 and runs with 116. Led in runs and on-base percentage in 1980. In 1982, he was part of a St. Louis Cardinal team that won the World Series. But manager-GM Whitey Herzog didn't like him, thought him arrogant and a cocaine user. Mex protested, but, as we now know, Whitey was right, and he's in the Hall now, and Mex isn't.

In the short term, though, Herzog made a big mistake in trading him to the Mets on June 15, 1983, for pitchers Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey. It may be the best trade the Mets have ever made, as in his 6 full seasons in Flushing, they finished 1st or 2nd in the NL East every year, including the 1986 World Championship, for which Hernandez was Captain.

He had a lifetime batting average of .296, OPS+ 128, 2,182 hits including 426 doubles and 162 homers, 11 Gold Gloves, 5 All-Star berths. Much as center fielders Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays were compared, so too were New York 1st basemen Hernandez and Don Mattingly. Strangely, both men's careers ended early due to bad backs, Hernandez not playing a full season after age 33, and playing his last game shortly before turning 37.

According to Baseball-Reference.com, their HOF Monitor has him at 86 out of 100 (meaning, no, he shouldn't get in), and their HOF Standards at 32 out of 50 (meaning, no). Their 10 Most Similar Players, weighted toward the same position the player played (though not necessarily all of them did), are Wally Joyner, Mark Grace, Hal McRae, Joe Kuhel, Ken Griffey Sr., Chris Chambliss, Cecil Cooper, Jose Cruz Sr., Joe Judge and Bob Elliott. None of them are in the Hall, and aside from Grace a case can't really be made for any of them.

But the above figures don't include defense, so maybe Hernandez, now a Met broadcaster, will one day make it through the Veterans Committee. After all, who does this guy think he is? "I'm Keith Hernandez!"

Dishonorable Mention to Hal Chase of Los Gatos, Santa Clara County, outside San Jose. Like Hernandez, "Prince Hal" was considered the best defensive 1st baseman of his time, and played in New York to much acclaim, with the Highlanders, forerunners of the Yankees. He was a good hitter, too, .291 lifetime with 2,158 hits.

But no player in the history of the sport is more associated with "throwing" games. Teammates used to see him mess up plays at 1st, and think, well, he's the best there is, so that bad play must have been my fault. No.

Ultimately, despite having played on 2nd-place teams with the Highlanders in 1906 and 1910, and even being a player-manager for a short time, he was banished from the club, and bounced around until last playing at age 36 in 1919. After that, though nothing was ever proven, his reputation was so tainted that only "outlaw leagues" – today we would call them "independent leagues," such as the Atlantic League or the Can-Am League – would take him.

2B Tony Lazzeri of Galileo H.S. in San Francisco. In 1925, he hit 60 homers for the Salt Lake City Bees of the Pacific Coast League – the 1st player in "organized ball" ever to hit 60 in a season. That got the Yankees' attention, and they bought him for 1926, and he starred for them for the next 12 seasons. His fellow Italian-Americans yelled, "Poosh 'em Up Tony," meaning push the runners up around the bases, and that became his nickname.

He became the victim of the most famous strikeout of all time that season, getting fanned by an aging, exhausted, possibly hungover Grover Cleveland Alexander with the bases loaded in the 7th inning of Game 7 of the World Series.

But Lazzeri would be part of Yankee World Champions in 1927, '28, '32, '36 and ’73. He was the AL's starting 2nd baseman in the 1st All-Star Game in 1933. He had a .292 lifetime batting average, 121 OPS+, and 7 100-RBI seasons – now that's pushing 'em up. Unfortunately, he also suffered from epilepsy – as did Alexander, in a morbid coincidence – and in 1946, aged just 42, he had a seizure, fell down the stairs in his house, broke his neck and died. In 1991, he was finally elected to the Hall of Fame.

Honorable Mention to Jerry Coleman of Percival Lowell H.S. in San Francisco. The most famous Yankee to wear Number 42 before Mariano Rivera, his double drove home the runs that clinched the 1949 AL Pennant. He was an All-Star in 1950, and helped the Yankees win the World Series in 1949, '50 and '51.

But, having already served in the Marines in World War II, he was called back early in the 1952 season to serve in the Korean War, and became a pilot, a hero by anyone's definition but his own. Lieutenant Colonel Coleman returned with 2 Distinguished Flying Crosses, as the only MLB player to see combat in 2 wars (though not the only one to serve in 2), toward the end of the 1953 season, but he was never the same as a player, and Billy Martin was now blocking his path.

He became a broadcaster, first with the Yankees, reunited with former double-play partner Phil Rizzuto; then with the San Diego Padres, for whom he was been their "voice" for almost their entire history until his death a few weeks ago. His Hall of Fame broadcasting career includes such moments as Mickey Mantle’s 500th home run and Steve Garvey's walkoff homer in Game 4 of the 1984 NLCS. His trademark phrase is, "You can hang a star on that baby!"

But he's also known for, well, I can't post them all here, but here’s a link, and try these 3: "Rich Folkers is throwing up in the bullpen." "On the mound for the Padres is Randy Jones, the lefthander with the Karl Marx hairdo." (He meant Harpo Marx.) "There's a fly ball, deep to right, Winfield goes back to the wall, he hits his head on the wall! And it rolls off! It's rolling all the way back to second base. This is a terrible thing for the Padres."

SS Joe Cronin of San Francisco. A another Sacred Heart Cathedral grad, he was the AL's starting shortstop in the 1st 3 All-Star Games, and 7 of the 1st 9. Starring for the Washington Senators, team owner Clark Griffith allowed him to become his son-in-law, and, at the tender age of 26, his manager. The result was a Pennant in 1933, and that remains the last Pennant any Washington baseball team has ever won.

But after the 1934 season, Boston Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey offered Griffith Lyn Lary and $225,000, and so Griffith traded his manager, his shortstop and his son-in-law – which would have been a big deal even if that were 3 men instead of 1!

Yawkey was a fabulously wealthy man who was trying to buy a Pennant. He ended up buying 4, but never bought a World Series win. Those Pennants included the 1946 one managed by Cronin, who had probably held the Sox back by refusing to vacate the shortstop position, where his skills quickly deteriorated, resulting in the sale of Sox farmhand Harold “Pee Wee” Reese to the Dodgers.

Eventually, Cronin gave way to Johnny Pesky, and the Sox were much better off. But the real reason the Sox finished 2nd in 1938, '39, '41 and '42 wasn't Cronin's managing, it was that the Yankees were the much better team. Yawkey kicked Cronin upstairs after he followed the '46 Pennant with a 3rd-place finish in '47, and Cronin remained Sox GM until 1959, when he became President of the American League. Interestingly, it was only when Cronin left the organization that the Sox, the last all-white team in the majors, finally integrated. (People have often blamed Pinky Higgins, who like Cronin was one of Yawkey’s drinking buddies, rather than Cronin.)

Cronin served as AL President until 1973, and was elected to the Hall of Fame. His Number 4 was retired by the Sox, and he is a member of both the Red Sox Hall of Fame and the Washington Wall of Stars at Nationals Park. It’s not just for his managing: .301 lifetime batting average, 119 OPS+, 2,285 hits including 515 doubles and 118 triples. (Legend has it that he was the first manager ever to tell a pitcher, "Don't give him anything good to hit, but don't walk him.")

Honorable Mention to Frank Crosetti of Santa Clara. Nobody has more World Series rings. As a player, he was the Yankees’ starting shortstop on their 1932, '36, '37, '38 and '39 World Champions. With the coming of Phil Rizzuto, the Crow was the backup in '41.

With the Scooter away in World War II, Crosetti was the starter in '43. He was a reserve in '47, and then became the 3rd base coach for the Yankee champions of '49, '50, '51, '52, '53, '56, '58, '61 and '62. So that's 8 World Championships as a player, and counting his coaching, he had 17. But was he a good player? In his 20s, he was, but by the time he turned 30, there was no doubt that Rizzuto was the best shortstop in the organization.

Honorable Mention to Eddie Joost of Mission H.S. in San Francisco. He was a 2-time All-Star for the Philadelphia Athletics. Ordinarily, this would not be odd, except that his All-Star seasons were in 1949 and 1952, well after Connie Mack broke up his last A's dynasty. In fact, when the A's were sold and moved out of Philadelphia in 1954, Joost was their last manager, playing out the string of a career that saw him win a Pennant in 1939 and a World Series with the Cincinnati Reds in 1940, before coming to the A's. He hit 134 home runs, a surprising number for a late 1940s-early '50s shortstop, and twice had an OPS+ of at least 133.

Honorable Mention to Jim Fregosi of San Francisco. Attended Father Junipero Serra H.S., an elite Catholic school in San Mateo, which would later produce Barry Bonds and Tom Brady – uh, maybe I shouldn't mention that, it might damage their reputation. Anyway, put aside for a moment the fact that getting hurt shortly after coming to the Mets in 1972 made their trade of Nolan Ryan for him look incredibly stupid: Fregosi was a hell of a player before that, with the team known from 1961 to 1965 as the Los Angeles Angels and from 1966 until well after he left as the California Angels.

He made 6 All-Star teams, won a Gold Glove, had a 113 OPS+ even with his injury-plagued 30s, got at least 140 hits, peaking at 171 (including at least 19 doubles, peaking at 33) every year from 1963 to 1970, and was the greatest player the Angels franchise had until the 1980s when guys like Reggie Jackson and Rod Carew arrived. His Number 11 was retired by the Angels, whom he managed to their first postseason berth in 1979. He also managed the Phillies to the 1993 NL Pennant. Like Coleman, he died within the past few weeks.

Honorable Mention to Jeff Blauser of Auburn, Placer County. A 2-time All-Star for the Atlanta Braves, he was part of their rise from pathetic to champions, winning 4 Pennants and the 1995 World Series with them. In 1998, he went to the Chicago Cubs, and helped them get into the Playoffs, too; however, an injury ended his career the next season, aged only 33.

Honorable Mention to Troy Tulowitzki of Sunnyvale, Santa Clara County. He's only 29, but he's already a 3-time All-Star. He got screwed out of the 2007 NL Rookie of the Year voting (Ryan Braun of Milwaukee had a great year offensively but can't carry Tulo’s glove), has a career OPS+ of 120, has 3 seasons batting .300 or better, 5 seasons of 24 or more home runs, and has reached the postseason twice (2007 World Series and 2009 NL West title) – twice as many postseason berths as the Colorado Rockies had ever reached before he got there.

3B Carney Lansford of Santa Clara. He helped the Angels win the 1979 AL West title, won the 1981 AL batting title at .336 with the Red Sox, and then became probably the best 3rd baseman in Oakland A's history, helping them to 4 AL West titles, 3 Pennants and the 1989 World Championship in 5 years. Injuries cut his career short at age 35, but a batting average of .290, an OPS+ of 111, and 2,074 hits showed him to be a very productive player.

Honorable Mention to Gil McDougald of San Francisco. A graduate of the University of San Francisco, he spent 10 years with the Yankees, beating out teammate Mickey Mantle for the 1951 AL Rookie of the Year award. A 5-time All-Star, Gil had a 111 OPS+, led the AL in triples and sacrifice hits in 1957, and helped the Yankees win 8 Pennants and 5 World Series. By his own admission, he was deeply disturbed by the line drive he hit back at pitcher Herb Score in 1957, and says he was never the same after that, either.

He retired after the 1960 season, age 32, and later coached at Fordham University before retiring due to hearing loss. He later regained some hearing through a cochlear implant, and became a paid spokesperson for the company that produced it.

And then there's Matt Williams of Bishop, Inyo County, in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. He grew up in Carson City, Nevada, and I never really decided which "region" should get Nevada's best. Nevertheless, the closest teams to Carson City, the Nevada State Capital on the California State Line near Lake Tahoe and Virginia City, are the Bay Area teams, the Giants and A's, and he played for the Giants, so that settles that.

He helped the Giants win the 1989 NL Pennant, the Cleveland Indians the 1997 AL Pennant, and the Arizona Diamondbacks the 2001 World Series, in the process becoming the only man (still) to hit home runs in World Series play for 3 different teams. A 5-time All-Star, he hit 378 homers, peaking at 43 in 1994 when the strike hit (he was on a pace to hit 61), and had 4 100-RBI seasons with a peak of 142 in 1999.

However, injuries began to take their toll when he was just 34, and at 37 he retired. And he went bald early. Steroids? He was mentioned in the Mitchell Report, and that’s why he's not the starter on this team.

One guy who did admit to steroid use was Ken Caminiti of Hanford, Kings County in the San Joaquin Valley, and San Jose State University. He probably didn’t need the juice. A 3-time All-Star and 3-time Gold Glove, he had been a really good player for the Houston Astros, before going to the San Diego Padres.

In 1994, he hit 18 homers and had 75 RBIs; within 2 years, he went to 26 and 40 homers, and 94 and 130 RBIs. In 1996, he won the NL's MVP, helping the Padres win the NL West. In 1998, he helped the Padres win the Pennant. In 1999 he went back to the Astros and helped them win an NL Central title. He finished with the Braves in 2001, winning an NL East title, with a career OPS+ of 116 and 239 homers.

But the steroids took their toll, and, dying, he wrote an article that appeared in Sports Illustrated, admitting he was killing himself with them. He died in 2004, aged just 41. He could still have been playing.

LF Francis "Lefty" O'Doul of Bay View H.S. in San Francisco. He started out as a pitcher with the Yankees, but never found the plate. After bouncing around the majors and the minors, he became an outfielder, and starred with the Salt Lake City Bees of the PCL (as a teammate of Lazzeri's), and learned how to hit like hell.

He returned to the majors with the 1928 Giants at age 31, and batted .319. In 1929, with the Phillies, he batted .398, an average that has only been topped twice since, and set an NL record that still stands with 254 hits. He won another batting title with the Dodgers in 1932, and went back to the Giants in 1933, appearing in the first All-Star Game and winning the World Series.

He left the Giants after 1934, going back to the PCL and his hometown San Francisco Seals (presaging the move of the Giants themselves by 23 years), remaining as a player-manager until he was 43 (with 2 more one-shot appearances at ages 47 and 48, and one more in Vancouver at 59) and managing them until 1951. O’Doul managed several future big-league greats with the Seals, including Joe and Dom DiMaggio.

O'Doul is not in the Hall of Fame, probably because he didn't have enough good seasons in the majors, and his PCL successes are not considered – and they should, because the PCL thought of itself as a major league, and the AL and NL as "the eastern leagues." As you can see by this list, and by the lists for the other West Coast teams, the West Coast produced more value than any gold or silver mine in the region.

O'Doul has been honored by the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame, and by the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame for his efforts at promoting the game there. Supposedly, he named Tokyo's top baseball team, the Yomiuri Giants, after the New York Giants, and suggested they use the same colors, orange and black.

The move of the Giants to San Francisco helped his legend, as Lefty O'Doul's Restaurant & Lounge in downtown San Francisco benefited by fans stopping by. A bridge over McCovey Cove, near the Giants' new home of AT&T Park, is named the Lefty O'Doul Bridge.

Dishonorable Mention to Barry Bonds of San Mateo. Here's a guy who had it all: Great bloodlines (his father Bobby Bonds was a perennial All-Star), looks, immense talent. From 1986 to 1998, he had made the All-Star team and won the Gold Glove 8 times each, had won 3 MVP awards, and reached 5 postseasons (although had never won a Pennant). And he had hit 411 home runs, and stolen 443 bases, making him the first to have 400 of each in a career. And at 1,917 hits, he looked like a sure bet for 3,000 hits, and for 600 home runs.

He was the best player in the game – maybe the 2nd-best behind Ken Griffey Jr. – and if he kept going, he could have been the best left fielder ever, and up there with guys like Babe Ruth and his own godfather, Willie Mays, for the title of greatest player ever.

The one thing he didn't have was the love of the fans. His own surly personality had prevented that. The key here is the date: 1998. He saw how Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa had electrified fans with their home run race, both breaking the previous record of 61 in a season by Roger Maris, and he saw how they were not just respected, as he was, but loved. He also thought they took steroids (and he was right). So he took steroids (and he was wrong).

I won't discuss the numbers he put up after 1998, but the thing that upsets me the most about him is that he didn't need to take performance-enhancing drugs. Without steroids, McGwire was broken-down at 29 and probably finished, and Sosa would've remained a question mark. Without steroids, Bonds was already one of the greatest ever. And he cheated anyway. He wanted the love of the fans? Except in San Francisco, he will never have it.

When The Sporting News announced its 100 Greatest Baseball Players in 1999, he came in at Number 34, then the highest-ranking active player. And that was, pretty much, based on what he did without juicing. But now, we'll never know.

CF Joe DiMaggio of Galileo H.S. in San Francisco. How do you sum up the Yankee Clipper? I will be as brief as I can. He won 10 Pennants and 9 World Championships. He was an All-Star 13 times – every season he played in the majors. (He missed 3 seasons, aged 28, 29 and 30, due to World War II service, and retired due to injury right after turning 37.)

He won 3 MVPs, and just missed 3 others. He had a .325 batting average, 155 OPS+. 2,214 hits in those 13 seasons, including 389 doubles, 131 triples, and 361 homers (all this despite playing in the pre-renovation Yankee Stadium with its vast left and center fields) with just 369 strikeouts. His .381 batting average in 1939 is the 2nd-highest in team history, behind Babe Ruth's .393 in 1924.

He had 9 100-RBI seasons and just missed 2 others. He had a 56-game hitting streak in 1941, the longest ever – only 2 men before, and 1 since, have even gotten to 40. There were no Gold Gloves in his day, but he was regarded as the best defensive outfielder until Willie Mays came along – and, to many, remained so. And, more so than the several singing stars and boxing champions that preceded him, became the first Italian-American celebrity that non-Italians embraced.

He was elected to the Hall of Fame. His Number 5 was retired by the Yankees. He received a plaque that became part of Yankee Stadium's Monument Park, replaced by a monument after his death. In 1969, he was named to an all-time team, and its "greatest living player," in honor of the 100th Anniversary of professional baseball. In 1999, shortly after his death, he was elected to the All-Century Team. That same year, when The Sporting News announced its 100 Greatest Baseball Players, he came in at Number 11.

New York's West Side Highway was renamed the Joe DiMaggio Highway (even though most people still use its original name).

My generation, who never saw him play, knows him through black-and-white highlight reels, the occasional trip to Yankee Stadium for Old-Timers' Day, and from his TV commercials for Mr. Coffee and the Bowery Savings Bank. (The Bowery is now a part of the Capital One system – and I'd sooner trust DiMag to ask me, "What's in your wallet?" than those… what are they, Vikings, Huns, Visigoths?)

When, in his song, "Mrs. Robinson," Paul Simon asked, "Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio? A nation turns its lonely eyes to you," he was using Joe D as an example of a reliable symbol of a more innocent time – as if the Great Depression, World War II and the early Cold War really were "innocent." DiMaggio's reaction to that line? "What do you mean, 'Where have I gone?' I haven't gone anywhere." He's been dead for 15 years now, and hasn't played in over 60 years. But he still hasn't gone anywhere: Joe DiMaggio is still with us.

Honorable Mention to Dominic DiMaggio, also of Galileo H.S. in San Francisco. One of the first players to wear glasses on the field, he was called the Little Professor. It seems unfair to compare Dom to his brother when he was very nearly of Hall of Fame quality himself: A 7-time All-Star (and it would have been more if he hadn’t gone off to war), a fine defender, a .298 lifetime hitter, a 111 OPS+, 1,680 hits including 308 doubles in just 10 full seasons. Strangely, he retired early – I can't find a reason, no apparent injury or illness.

He helped the Red Sox win the 1946 Pennant, and nearly 2 others in 1948 and 1949. He led the AL in runs, triples and stolen bases in 1950, and runs again in 1951. He is member of the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame and the Red Sox Hall of Fame, but not the big one in Cooperstown. Maybe if he’d played longer…

In case you’re wondering, older brother Vince DiMaggio was also a center fielder, and a 2-time All-Star with the Pirates. Unfortunately, while he did have 100 RBIs in 1941, he also led the NL in strikeouts 6 times, fanning 837 times in his career. Joe and Dom, combined, only struck out 940 times.

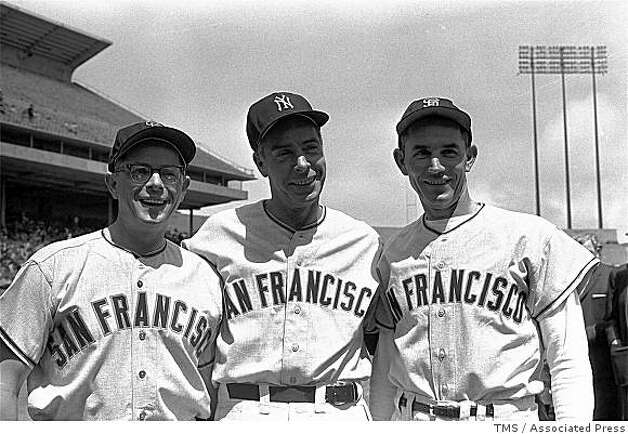

That photo at the top of this article shows the brothers at an old-timers' celebration at Candlestick Park in the 1960s -- all wearing Giants away uniforms so that they read "SAN FRANCISCO." That's Dom on the left, Joe in the center, Vince on the right. Joe is wearing a Yankee cap, the others Giants caps.

RF Harry Heilmann of Sacred Heart Cathedral H.S. in San Francisco. He was a really good hitter in even-numbered years: .356 in 1922, .346 in 1924, and .367 in 1926. But he must've been signing 2-year contracts that ended in odd-numbered years, because check these batting averages out: .394 in 1921, .403 in 1923, .393 in 1925, and .398 in 1927, all winning AL batting titles. Ty Cobb, his teammate on the Detroit Tigers from 1914 to 1926, must've had a good influence on him.

His lifetime batting average was .342, his OPS+ 148, 2,660 hits including 542 doubles and 151 triples. He played before uniform numbers were worn, but he is in the Hall of Fame. When The Sporting News announced its 100 Greatest Baseball Players in 1999, he came in at Number 54.

Honorable Mention to Harry Hooper of Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz County. Along with Duffy Lewis and Tris Speaker, he formed one of the greatest outfields of all time. He helped the Red Sox win World Series in 1912, 1915, 1916 and 1918. He had a 114 career OPS+, 2,466 hits, 389 doubles, 160 triples, and 375 stolen bases. He was often considered the best defensive right fielder of his era. Hall of Fame.

C Gus Triandos of Mission H.S. in San Francisco. The Yankees had Yogi Berra and Elston Howard, so it was no big deal to them to let him go in the same post-1954 trade that sent away Gene Woodling but brought in Bob Turley and Don Larsen.

But the trade worked out well for the Baltimore Orioles, who got a 3-time All-Star who hit 156 homers over the next 9 years, despite playing his home games at Memorial Stadium. His expertise helped build the first good Oriole pitching staff, enabling them to win 89 games and finish 2nd to the Yankees in 1960, the closest any Baltimore baseball team had gotten to a major league Pennant in 62 years. He was not only out of Baltimore but out of baseball by the time the Orioles won their first Pennant and World Series in 1966, but they wouldn't have gotten that far without his earlier efforts.

SP Vernon “Lefty” Gomez of Richmond H.S. in San Francisco. "He was fast with a quip and a pitch," says his Plaque at Monument Park at Yankee Stadium. One such quip was, "I'd rather be lucky than good." He was both.

He only had 10 full seasons, and his last good one was at age 32, but he was 189-102 for his career, and 6-0 in World Series play. He won 20 games 4 times, including a 26-5 record in 1934 -- no Yankee has matched, let alone topped, 26 wins since. (Two have reached 25: Whitey Ford 1961 and Ron Guidry in 1978. On the other New York teams, Don Newcombe won 27 in 1956, Carl Hubbell 26 in 1936 and Tom Seaver 25 in 1969.)

He was named to the 1st 7 All-Star Games and started the 1st 2 (both against Carl Hubbell). He was a member of 7 Pennant winners and 6 World Championships: 1932, '36, '37, '38, '39 and '41. Hall of Fame, and as I said, a Monument Park Plaque, although his Number 11 remains in circulation. When The Sporting News announced its 100 Greatest Baseball Players in 1999, he came in at Number 73.

SP Mike Garcia of Visalia, Tulare County, in the San Joaquin Valley. The Big Bear was twice a 20-game winner and twice an AL ERA champion for the Cleveland Indians. He only got into one game in their 1948 World Championship season, but in 1954 went 19-8 with a league-leading 2.48 ERA to help them win a League-record 111 games and the Pennant. He finished 142-97 with an ERA+ of 118.

SP Jim Maloney of Fresno. He was one of the fastest pitchers of all time. He was still finding his way when the Reds won the Pennant in 1961, but had 2 20-win seasons on his way to a career record of 131-84, with an ERA+ of 116 and 1,605 strikeouts. In 1965 he pitched a no-hitter for 10 innings, but lost it and the game in the 11th. So, later that season, he pitched another 10-inning no-hitter, and this time the Reds scored in the 10th and won it for him. He pitched a 3rd no-hitter (MLB doesn't give him credit for the first, even though he started and pitched 9 hitless innings) in 1969.

All that heat, and all those extra innings, must've taken their toll, because he was finished at 31, and was unable to pitch with the Big Red Machine of the 1970s, appearing in just 7 games for the Reds' 1970 Pennant winners before being traded.

Because his career ended early, and he didn't pitch in a major media market like Whitey Ford and Tom Seaver in New York, or Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale in Los Angeles, or Juan Marichal in San Francisco, and he didn't appear in a bunch of World Series games like Ford and Seaver and Koufax and Drysdale and Bob Gibson, he gets forgotten. Still, the Reds have elected him to their team Hall of Fame, and he's the 2nd-best former Cincinnati pitcher in this rotation.

SP Tom Seaver of Fresno. Okay, we don't generally think of him for his 1977 to 1982 tenure with the Reds. For the Mets, he was The Franchise, the man who, more than any other except manager Gil Hodges, made them respectable, let alone 1969 World Champions. That year, the man who 2 years earlier had won the NL Rookie of the Year went 25-7 with a 2.21 ERA, and helped the Mets win the World Series -- ironically, he lost Game 1 before winning Game 4 with a gutsy 10-inning, 1-run effort.

In 1970, he tied what was then the record by striking out 19 batters against the San Diego Padres, including a still-record 10 in succession. He won Cy Young Awards in 1969, 1971 and 1975. He had 5 20-win seasons, probably missed a 6th due to the 1981 strike (he was 14-2), and probably missed 2 others because the Mets had hitting troubles. He led the NL in ERA 3 times (including a miniscule 1.76 in 1971) and strikeouts 5 times (his 283 in 1970 and 289 in 1971 are the 2 best totals in Met history, ahead of Dwight Gooden's 276 in 1984). He never pitched a no-hitter for the Mets (no one has, in 49 seasons), but in 1978 he pitched one for the Reds.

He struck out 3,640 batters, his 3,000th victim being another member of this team and a future Met legend, Keith Hernandez. He finished 311-205, his 300th victory coming in 1985 with the Chicago White Sox, against the Yankees at Yankee Stadium. I was there, and I still have the ticket to prove it. (I tried to donate it to the Hall of Fame. I wanted the honor of having something of mine in their displays. They graciously mailed it back, saying they had enough artifacts from that game and I should keep it for my collection.) He closed his career with the Red Sox in 1986, ironically facing the Mets in the World Series, although he was not on the active roster.

He was the 1st player generally associated with the Mets to be elected to the Hall of Fame, and the first Met player to have his number retired. (Although Hodges did finish his playing career with the Mets, his Number 14 is retired for what he did as a manager.) To this day, a generation of New York Tri-State Area natives can't see the Number 41, in any form, without thinking of "Tom Terrific." When The Sporting News announced its 100 Greatest Baseball Players in 1999, he came in at Number 32.

He's gone into broadcasting, written a few books about baseball, and returned to his native San Joaquin Valley to grow wine. When the Mets closed Shea Stadium in 2008 and opened Citi Field the next spring, he was the ideal person to throw the ceremonial pitches. You would have to go a long way to find a more class act than George Thomas Seaver, and probably no one in my lifetime has better handled the fame that has come from being a New York sports superstar.

Reggie Jackson, who opposed him in the 1973 World Series with the A's and served as a generation's touchstone for the Yankees the way Seaver did for the Mets, paid Seaver an unforgettable compliment: "Blind people come to the park just to listen to him pitch."

SP Mark Langston of Santa Clara. Three times he led the AL in strikeouts, but the Mariners didn't want to pay his salary, so they traded him -- to the Montreal Expos, for an as-yet-unknown Randy Johnson, among others. He went 12-9 as a rent-a-pitcher for the Expos, and then they let him get away to the Angels, whom he gave 8 seasons, becoming perhaps their 2nd-best starter ever after Nolan Ryan.

Although he grew up outside San Jose, and went to San Jose State University, he was born in San Diego, and helped his original-hometown Padres win the Pennant in 1998. He thought he had Tino Martinez struck out in Game 1, before giving up a tremendous grand slam. The Indians signed him afterward, thinking they were going to face the Yankees in the postseason again, and thinking, "The Yankees can't hit lefthanders, especially in the postseason." (This also didn't work the next few years with Chuck Finley.) Langston was 38 and done, but he did win 179 games and strike out 2,464 batters.

Honorable Mention to Gary Nolan of Oroville, Butte County. Only the 3rd-best former Cincinnati pitcher on this team, and like so many others, he got his career cut short by injury, throwing his last big-league pitch at age 29 and finishing at 110-70 with an ERA+ of 117. But he had more luck with the Reds than Maloney or Seaver, pitching on their 1970 and 1972 Pennant winners and their 1975 and 1976 World Champions, beating the Yankees in the clinching Game 4 in '76.

Honorable Mention to Mike Norris of Balboa H.S. in San Francisco. He went 22-9 for the A's in 1980, finishing 2nd to a 25-win Steve Stone of Baltimore in the Cy Young Award voting, as Billy Martin and his exciting young team saved Major League Baseball in the East Bay for at least another generation. In the strike-shortened 1981 season, Norris went 12-9 as the A's won the AL West.

But "Billyball" meant pitchers burned out quickly, and that, coupled with a cocaine addiction, led to Norris flaming out, and he was out of baseball after the 1983 season at age 28. He beat the coke, and tried 2 comebacks, and actually reached the A's again, making 14 relief appearances and going 1-0 for their 1990 Pennant winners.

RP Dave Righetti of San Jose. He came to the Yankees from the Texas Rangers in the post-1978 trade for Sparky Lyle. He was the AL Rookie of the Year in 1981, leading the League with a 2.05 ERA as the Yankees won the Pennant. He went 14-8 in 1983, including a July 4 no-hitter against the Red Sox.

But in 1984, the Yanks needed to replace Goose Gossage as their closer, and sent "Rags" to the bullpen. It seemed to work, including 46 saves in 1986, a major league record that stood for 4 years, a lefties' record that stood for 7, and still an AL record for lefties. He made 2 All-Star teams, and was the first pitcher ever to both pitch a no-hitter and lead a league in saves, and only Dennis Eckersley has joined him since.

But the Yanks never reached the postseason with him again, and after the team crashed to last place in 1990, he signed as a free agent with his "hometown" Giants. At 31, he never had another good season. But he did save 252 games in his career, and win 82 others, compiling an ERA+ of 114. Since 2000, he has been the Giants' pitching coach.

Honorable Mention to John Wetteland of Santa Rosa, Sonoma County. If you're the general manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, be glad the Montreal Expos no longer exist, because at almost the same time, they traded both Wetteland and Pedro Martinez to the Expos, and both were big mistakes. In 1994, the Expos had the best record in baseball when the strike hit, and he and Pedro were 2 big reasons why.

In the offseason, deciding they couldn't afford to keep him, the Expos traded him to the Yankees for Fernando Seguignol and cash. Who? Never mind, the key part of the deal was the cash. Wetteland helped the Yanks back into the postseason in 1995, and in 1996 he saved 43 games, including 7 in the postseason -- including all 4 World Series wins, and he was named Series MVP.

But with Mariano Rivera ready to graduate from setup man to closer, the Yanks let him go via free agency. He signed with the Rangers, and gave them 4 strong seasons, including AL West titles in 1998 and '99, before retiring at age 33, despite not being injured. I guess he'd had enough. He saved 330 games, including more than any other pitcher in the 1990s and more than any other pitcher in Rangers history. He is a member of the Rangers' team Hall of Fame.

Friday, March 28, 2014

San Francisco's All-Time Baseball Team

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment