* New York Mets: Darryl Strawberry, Dwight Gooden and David Cone. (But not Joe Torre. Or Yogi Berra.)

* Boston Red Sox: Wade Boggs. (But not Roger Clemens.)

* Oakland Athletics: Reggie Jackson and Catfish Hunter.

* St. Louis Cardinals: Enos Slaughter.

* Cleveland Indians: Bob Lemon.

* Brooklyn (now Los Angeles) Dodgers: Red Barber.

* San Diego Padres: Dave Winfield and Jerry Coleman.

That's about it. And it is, for a sad reason, the last of these names that I post tonight.

Gerald Francis Coleman was born on September 14, 1924, in San Jose, California. He was one of many Yankees in the pre-1957 era, before the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles and the Giants moved to San Francisco, to have been plucked from the rich "farmland" of the Pacific Coast League.

He was a graduate of Lowell High School, named for poet James Russell Lowell, in San Francisco. Other graduates of this distinguished institution include scientist Rube Goldberg, artist Alexander Calder, California Governor Pat Brown (father of current Governor Jerry Brown), Hewlett-Packard co-founder William Hewlett, videotape pioneer Charles Ginsburg, actress Carol Channing, President Kennedy's Press Secretary Pierre Salinger, Gorillas in the Mist author Dian Fossey, actor Bill Bixby, The Gap founder Donald Fisher, Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, his brother and fellow federal Judge Charles Breyer, Star Trek costume designer William Ware Theiss, Golden State Warriors legend Tom Meschery, Dennis Marcellino of Sly's Family Stone, San Diego Charger defensive back Gill Byrd, writer Naomi Wolf, actor Benjamin Bratt, Lemony Snicket author Daniel Handler, and Walter Haas, the Levi Strauss magnate who bought the A's from Charlie Finley and saved them for the Bay Area for 2 generations. (Whether there will be a 3rd remains to be seen.) Graduating with Coleman in 1942 was Art Hoppe, longtime columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle.

The Yankees scouted and signed him, and played out the 1942 in Class D ball, before enlisting in the Marine Corps and becoming a pilot. He would also fly for the Marines in the Korean War. A few players, including Ted Williams, would serve in both of those wars, but Coleman was the only major league player to see combat in 2 wars -- any 2 wars. (Hank Gowdy was the only player to have served in World Wars I and II, and was the first player to enlist in I, but wasn't in combat for II.)

When he got back, he rose quickly, playing for the Binghamton Triplets and the Kansas City Blues in 1946, the Blues exclusively in 1947, and the Newark Bears in 1948. He made his major league debut on April 20, 1949, at Yankee Stadium, leading off, playing 2nd base, and going 0-for-4 against the Washington Senators. To make matters worse, on the very first batter he ever faced, Gil Coan, he muffed a grounder for an error. He made up for it, though, starting an inning-ending double play. This helped Vic Raschi to pitch a shutout, and a home run by Tommy Henrich helped the Yankees win, 3-0.

He got his 1st major league hit the next day, a single off Senator pitcher Forrest Thompson, in a 2-1 Yankee win, and he was on his way. When that season came down to the last 2 games, with the Yankees needing to win both at home against the Red Sox, or else the Sox would win the American League Pennant, Coleman got a hit in both games. The finale was won by his bases-loaded double in the bottom of the 8th, of Tex Hughson, as the Yankees won, 5-3, and took the Pennant. He batted .275 that year, with 2 homers and 42 RBIs, and finished 3rd in the first-ever AL Rookie of the Year balloting, behind Roy Sievers and Alex Kellner.

He made his only All-Star Team in 1950, batting .287 with 6 homers and 69 RBIs. In his 1st 3 seasons, 1949, '50 and '51, the Yankees won the World Series every year. But after just 11 games in '52, he was called back by the Corps, and flew missions over Korea. He received 13 Air Medals and 2 Distinguished Flying Crosses, rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, and was known as "The Colonel" for the rest of his life. (This meant that he outranked "The Major," WWII vet Ralph Houk, his teammate as a player and the manager for much of his time as a Yankee broadcaster.) He was discharged in time to play in the last 8 games of the 1953 season, but not in time to be eligible for the World Series roster.

The 1955 World Series was the 1st and only won by the Brooklyn Dodgers. In Game 1 (which the Dodgers, everyone forgets, lost), Jackie Robinson stole home plate. To this day, Yogi Berra insists that Jackie was out. So does Whitey Ford, who was pitching that day. The film seems to bear them out. But Phil Rizzuto said that he had the best view of the play, at shortstop, and that Jackie was safe.

Whitey got tired of hearing the Scooter say this, so he looked it up. It turned out that, in the bottom of the 6th, Eddie Robinson (no relation to Jackie) had pinch-hit for Rizzuto, and Coleman had gone into to play short, and he was there when Jackie stole home in the top of the 8th! The Scooter's memory must have been playing tricks on him. Coleman's thoughts on the steal, as far as I know, were never recorded.

Coleman won another World Series with the Yankees in 1956, and another Pennant in 1957, but was released after that season, shortly after his 33rd birthday. His lifetime batting average was .263, his OPS+ a mere 83, with 558 hits, 16 homers and 257 RBIs. A decent player, but, clearly, he wasn't going to get into the Baseball Hall of Fame that way. For the entirety of his playing career, he was with the Yankees, and wore Number 42, making him the greatest Yankee to wear the number until Mariano Rivera.

In the 1958 and '59 seasons, he served as the Yankees' personnel director, effectively making him their chief scout. In 1960, he began broadcasting baseball with CBS, and in 1963 was hired to broadcast Yankee games.

My Grandma told me that, when Coleman and his former double-play partner Rizzuto used to get going, it was a riot. Sadly, there doesn't seem to be any surviving broadcasts of their banter. Red Barber was also there until 1966, and Jerry picked up the phrase "Oh, doctor!" from him. He also used phrases like, "You can hang a star on that baby!", "And the beat goes on" (presumably before Sonny & Cher recorded their song with that title), and "The natives are getting restless."

His most notable moment behind the microphone for the Yankees was his call of former teammate Mickey Mantle's 500th career home run, off Stu Miller of the Baltimore Orioles, on May 14, 1967, on WPIX-Channel 11. Because of the significance of the milestone (only 5 players had done it before Mantle), this is one of the rare surviving color videotape clips from the pre-renovation original Yankee Stadium.

After the 1969 season, Coleman left the Yankees, and broadcast for the California Angels for 2 years. In 1972, he joined the broadcast staff of the San Diego Padres, and remained in their booth for the rest of his life. With one exception: In the 1980 season, the Padres named him their manager. This proved to be a bad idea, as the Padres went just 73-89, and finished last in the National League Western Division.

In an oddity, he almost wasn't the only beloved broadcaster-turned-manager that year. After Dallas Green was the Philadelphia Phillies' manager at the end of the 1979 season, the Phils considered offering the job to Richie Ashburn, who had also been their star center fielder in the 1950s. But Phils owner Ruly Carpenter realized that, eventually, he would have to fire him, and he didn't want to go down in history as "the man who fired Richie Ashburn."

So he gave Green the job for the full season, and the Phils won their 1st World Series that year. The Padres made the decision to move their beloved broadcaster into the manager's job, and may have been the NL's worst team; the Phils didn't, and were baseball's best.

As the voice of the Padres, Coleman was behind the mike for postseason runs in 1984, 1996, 1998, 2005, 2006 and 2007 (if you count the Wild Card play-in game, and I do). His biggest moment was calling the walkoff home run of Steve Garvey in Game 4 of the 1984 NLCS, setting up the next day as the Padres won their 1st Pennant. (You'll want to skip ahead to 2:12 on this clip, so you don't have to see those "Cub-busters" T-shirts and, worse, hear that "Ballbusters" song.)

* "There's a fly ball, deep to right field, Winfield goes back to the wall, he hits his head on the wall! And it rolls off! It's rolling all the way back to second base! Oh, this is a terrible thing for the Padres!" (Maybe he should have said, "Oh, doctor!")

* (Seeing the Padres' ace, with his Harpo Marx-like hair) "On the mound for the Padres is Randy Jones, the lefthander with the Karl Marx hairdo."

* "Rich Folkers is throwing up in the bullpen."

The line "He slides into second with a standup double" has been attributed to Coleman, Cleveland Indians pitcher-turned-announcer Herb Score, Pittsburgh Pirates slugger turned Mets broadcaster Ralph Kiner, and probably a few others.

He was honored with a star (appropriately enough) on the wall at San Diego/Jack Murphy/Qualcomm Stadium, and now at Petco Park, in place of a "retired number." Along with Tony Gwynn, he is also honored with a statue at Petco Park.

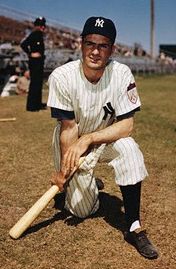

(Not the statue. This is him throwing out

the first ball at the Padres' 2012 home opener.)

For the last few years, he had understandably cut his broadcast schedule back to 30 games a year. A few days ago, as is the case with too many old people who had previously been in good health, he was injured in a fall at home, and went downhill quickly. He died today, at the age of 89.

*

With his death, the following players remain living from the Yankees' 1949 World Champions: Yogi, Whitey, Bobby Brown and Charlie Silvera.

They are also the only survivors from the 1950 World Champions, although only in '49 was Silvera on the World Series roster.

From the 1951 World Champions, surviving are those 4 and Bob Kuzava.

From the 1956 World Champions, surviving are Yogi, Whitey, Don Larsen, Bob Cerv, Norm Siebern, Jerry Lumpe and Billy Hunter, better known as Earl Weaver's longtime 3rd base coach with the Baltimore Orioles, and briefly manager of the Texas Rangers. Irv Noren, also a survivor of the '52 and '53 Champs, played for the Yankees in '56 but missed much of the season with injury, including the World Series, but should also be counted as a survivor of that team. Jim Coates is still alive, but only appeared in 2 games in '56 and was not on the Series roster.

Jerry Coleman was an American hero and a Yankee Legend. Now, he becomes one of "the Ghosts of Yankee Stadium."

Semper Fi, Colonel. Ooh-rah!

UPDATE: Jerry was buried at Miramar National Cemetery in San Diego.

3 comments:

Great Article! I still remember his 1984 Steve Garvey home run call as a kid. Our family went crazy.

Thank you, David. "Houston Cars," I do not allow spam on this page.

Post a Comment