October 16, 1969, 40 years ago today: Yes, it happened. Was it actually a "miracle"? Not really: The Mets unquestionably outplayed the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. That's what happens when you peak in the 1st at-bat of the Series (Don Buford's leadoff home run) and then presume that the Series is going to be a cakewalk.

In Game 5, with the Orioles leading 3-0 in the bottom of the 6th, Cleon Jones‚ the only Met to have hit .300 – in fact, his .340 remained a Met single-season record until John Olerud's .359 in 1998 – is hit on the foot with a pitch, much like the unrelated Nippy Jones of the Milwaukee Braves in the 1957 World Series. And, like Nippy, Cleon proves he was hit by showing the umpire a shoe-polish stain on the ball.

He is awarded 1st base, and then Donn Clendenon hits a home run to make it 3-2 Baltimore. Al Weis ties it up in the 7th, and in the 8th, Ron Swoboda doubles, and the O’s uncharacteristically make 2 errors, leading to Mets 5, Orioles 3.

Jerry Koosman goes the distance. Just as the 1999 film Frequency used the '69 World Series as a major plot point, connecting the past with that film's present, so, too, does the final out link the Mets' 2 and, so far, only World Championships. The last Oriole batter is 2nd baseman Dave Johnson. Or, as he was sometimes known, Davey Johnson. And 17 years before he manages the Mets to the 2nd title, he flies to left, where Cleon Jones is under it, and that's the 1st title.

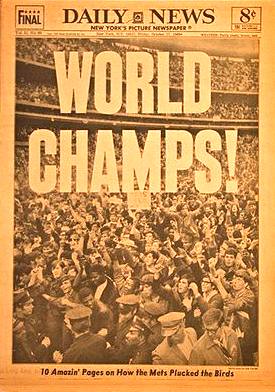

As Curt Gowdy said on NBC, "There's a fly ball to left, waiting is Jones, he's under it, the Mets are the World Champions! Jerry Koosman is being mobbed! Look at this scene!"

Thousands upon thousands of fans ran onto the field and took whatever souvenirs they could find, a repeat of the September 24 Division clincher and the October 6 Pennant clincher, and then some.

Joy. It was pure joy. It was a moment that required no explanation. No analysis. Just enjoyment.

But after 40 years, I’m going to analyze it, because it does sometimes seem hard to understand why it happened. The term "miracle" gets thrown around.

Samuel L. Jackson, as Jules Winnfield in Pulp Fiction: "What is a miracle, Vincent?"

John Travolta, as Vincent Vega: "An act of God."

Jules: "And what is 'an act of God'?"

Vincent: "When, um, God makes the impossible possible. But this morning, I don't think, qualifies."

George Burns, as God in Oh, God!: "The last miracle I did was the '69 Mets."

Tom Seaver, in the locker room after Game 5: "God is living in New York, and he's a Mets fan."

No. The Mets winning the 1969 World Series was not God interceding on behalf of a baseball team. Presuming that God exists, and I believe He does, do you really think He cares whether one sports team wins a contest, rather than the opposing team?

I suppose the televangelists Pat Robertson, Oral Roberts, and the late Jerry Falwell must have wondered why the teams at the colleges they founded (Regent University, Oral Roberts University and Liberty University) haven't done better than they have.

Nor do I suspect that that God interceded on behalf of New York City. If He was going to do that, wouldn't He have brought down the crime rate, or the poverty rate, or sent a message to the guys then building the World Trade Center to use more flame-resistant steel, or, I don't know, helped the Mets win more, or put up a Subway Series sometime between 1956 and 2000?

No. The Mets winning the 1969 World Series was not a miracle. It was not an act of God. It was a series of acts by men, resulting in a surprise result of a sporting contest. And here's why I think it happened:

Top 10 Reasons Why the Mets Won the 1969 World Series

10. The Cubs' September Swoon. Even winning 38 of their last 49 wouldn't have mattered for the Mets if the Cubs hadn't collapsed, losing 17 of 25 in one stretch, going from 9½ up on the Mets on August 19 to 8 games back at the end. That's a 17½-game swing.

If the Cubs had simply split those 17 losses, plus 1 win, going 17-8 instead of 8-17, and one of the 17 was the September 8 "Black Cat Game," which the Mets dubiously won 3-2 on a blown call at home plate that allowed Tommie Agee to score the winning run, the Cubs would have won the NL East, and the '69 postseason would have been a very different story.

Would the Cubs have beaten the Braves for the Pennant? Would they then have beaten the Orioles for the whole thing? They were the Cubs, so they would have found a way to lose, right?

Ah, but 1969 was the year the Cubs got that image in the first place. They weren't that team yet.

9. The Atlanta Braves' pitching. The Braves scored 15 runs in the 3 games of the NLCS, or 5 per game. But they allowed 27, an average of 9. A 5-run 8th off Phil Niekro in Game 1, getting 11 runs off Ron Reed and 5 Brave relievers in Game 2, and 5 runs in the 4th and 5th to chase Pat Jarvis in Game 3 showed the Braves that the Mets were no fluke.

Would the Braves have beaten the Orioles in the Series? I doubt it.

8. The Bullpens. The Mets only needed 5 2/3 innings of relief, but Don Cardwell, Ron Taylor, and a young fireballer from Texas named Nolan Ryan allowed no runs. (In 27 years of big-league pitching, it was Ryan's only ring. And while Tug McGraw was on the Met roster for this Series, he did not appear in it.)

A 2.06 ERA for your starters is excellent, but if the bullpen blows it, it won't mean much; but the Met bullpen had a 0.00 ERA. In contrast, the Oriole bullpen blew Game 4 for Mike Cuellar and Game 5 for Dave McNally.

7. Defense. The pair of catches by Tommie Agee in Game 3, and the Ron Swoboda catch in Game 4, get the headlines. But it wasn't just that the Mets' fielding was spectacular. It's that it was (almost) completely competent. They did commit 4 errors in the 8 postseason games, but no runs scored as a result.

The Mets allowed only 9 runs in the 5 games, or 1.444 runs per game. None of those 9 runs scored as a result of a Met error. No unearned runs. Throw in the NLCS, and in the '69 postseason, the Metropolitans allowed a total 24 runs in 8 games, or 3 runs per game, and none were unearned.

If your fielders can avoid betraying your pitchers, and your pitchers don't betray themselves, you're going to give your offense the chance to win the game. Which leads to...

6. "Good Pitching Beats Good Hitting." The O's collected only 23 hits, for a .146 batting average. Boog Powell led the Orioles with 5 hits, all singles, no RBIs.

Don Buford collected 2 hits in the opening game, including the leadoff home run against Seaver, but went 0-for-16 the rest of the way. Paul Blair went 2-for-20, Davey Johnson 1-for-15 and Brooks Robinson 1-for-19. The Baltimore offense, best in the majors in 1969, only managed four extra-base hits off Mets pitching in the 5 games.

Earl Weaver described "The Oriole Way" as "Pitching, defense and three-run homers." The only home runs the O's hit in the Series were Buford's leadoff, a solo shot by Frank Robinson in Game 5, and, amazingly, a 2-run shot by McNally (a pitcher! At Shea!) also in Game 5. That's 3 homers, for 4 runs, in 5 games, from a killer lineup.

Frank Robinson had 1,812 RBIs in his long and distinguished career. He had 4 in the '61 Series, 3 in '66, 4 in '70 and 2 in '71. He had just the 1 in '69.

Then again...

5. "Good Pitching Will Beat Good Hitting, and Vice Versa." That's what then-Met coach Yogi Berra once said. Allegedly. One thing he definitely said, after this Series, was, "We were overwhelming underdogs." Unlike a lot of things Yogi has allegedly said, this one is not weird at all, and was totally right.

The Mets faced Mike Cuellar in Games 1 and 4, Dave McNally in Games 2 and 5, and Jim Palmer in Game 3. Palmer is in the Hall of Fame, and Cuellar and McNally are not far from Hall-worthiness. But the Mets got the hits they needed when they needed them.

4. Hunger. It had been 5 years since New York had a World Series appearance. It had been 12 years since Met fans, most of them previously fans of the New York Giants or Brooklyn Dodgers, lost their old teams. It had been 13 years since the Dodgers last won a New York Pennant, 15 years for the Giants. And it had been 14 years since the '55 Dodger title, 15 years since the '54 Giant title.

And New York was in a hell of a mess in '69, with rising crime, bad weather (the February blizzard), poverty, racial discontent, the sense that the whole world was spiraling out of control, and the feeling that Mayor John Lindsay didn't know what the hell to do, with anything.

By contrast, Baltimore, certainly not without urban woes, had won the Series just 3 years before, and there was no "once-in-a-lifetime" or "team of destiny" feel about them as there was with the Mets, which the O's proved by winning it all the next season, and taking the next to Game 7.

3. O is For Overconfident. The Orioles didn't take the Mets seriously. True, the Mets had only 1 .300 hitter (Jones), and only 1 hitter with at least 20 homers and only 1 with at least 70 RBIs (in each case, Agee). But they were fundamentally sound, they had very good pitching, they won 100 games (you don't do that by being worthy of underestimation), they came from well behind to win the NL East, and they swept a pretty good Braves team in the NLCS.

Yet the O's acted as though their attack, pitching, defense and 109 wins would scare the Mets. Those Mets were a lot of things in 1969, but one thing they most definitely were not was scared. In large part because of…

2. Gil Hodges. Earl Weaver, the Baltimore manager, ranted and raved and lost his cool. Gil Hodges never, ever lost his cool. Not in the 1952 World Series, when he went 0-for-21 for the Dodgers. Not in the 1955 World Series, when he redeemed himself with some big hits and caught the last out of the only Series that Brooklyn would ever win. Not in the Summer of '69, when the Cubs seemed like sure Division titlists at least, and Met fans would have been overjoyed with a strong, if not especially close, 2nd-place finish.

And Hodges kept his cool in the '69 postseason as well. As a result, he kept the Mets calm, on an even keel, and let them know that they were worthy of this moment, even when few people outside the New York Tri-State Area believed (and 4 years before McGraw started using the slogan "Ya Gotta Believe").

And maybe that's it, the real reason the Mets won it all:

1. Nothing to Lose. If the Mets had finished 2nd to the Cubs in the new 6-team NL East, after 7 seasons of either 9th or 10th in the single-division 10-team NL, most Met fans would have gladly taken it. If they had won the Division but lost the Pennant to the NL West Champion Braves, it would have been a disappointment, but they would have gotten over it.

And if they had won the Pennant but lost the Series to the overwhelming favorite Orioles, it would have been fairly easy to take, as just being in the World Series is quite an honor – that is, so long as you don't lose it on a bonehead move or play, as the Red Sox did against the Mets in '86 (and I mean John McNamara's managerial decisions and Bob Stanley's wild pitch, not Bill Buckner's error), or as the Mets did against the Yankees in 2000 (the baserunning blunders and Armando Benitez's walk of Paul O'Neill).

Like the New England Patriots against the St. Louis Rams in their 1st Super Bowl win, or the Giants against the Patriots 7 years later, the Mets acted as if there was no pressure, as if the pressure was all on the other guys. The Mets had fun. And their fans had fun. It was fun they did not expect to have. And sometimes, that's the best kind of fun of all.

And that’s why the win was not just glorious, but, to use the cliché, Amazin'.

But I still hate the Mets.

Friday, October 16, 2009

The "Miracle" at 40: Top 10 Reasons It Happened

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment