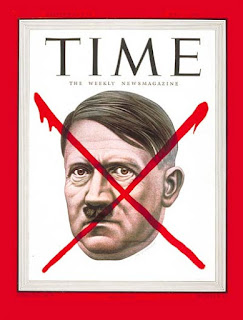

Date unknown, but it appears to be at the Vatican.

He's smiling as if he knew he had the perfect picture for his job.

On August 6, 1978, the Yankees beat the Baltimore Orioles, 3-0 at Yankee Stadium. Jim "Catfish" Hunter pitched a 5-hit shutout. While WPIX-Channel 11 was broadcasting the postgame show, the news arrived that Pope Paul VI had just died. And Yankee broadcaster Phil Rizzuto, Italian and very much Catholic, said, "Well, that kind of puts the damper on even a Yankee win."

On August 26, a new Pope was elected. He took the name John Paul I, after the last 2 Popes: John XXIII and Paul VI. But on September 28, on just his 33rd day on the Papal throne, he had a heart attack, and died.

The American League Eastern Division race between the Yankees and the Boston Red Sox was coming down to the wire. The Yankees beat the Toronto Blue Jays, 3-1 at Yankee Stadium, while the Red Sox beat the Detroit Tigers, 1-0 at Fenway Park in Boston. The teams were separated by only 1 game and the conclusion of the games.

That night, on radio station WBCN, 98.5 FM (now WWBX, 104.1), in Boston, perhaps the most Catholic city in America, disc jockey Charles Laquidara earned himself a lot of hate mail by beginning his broadcast with this teaser: "Pope dies, Sox still alive."

Four days later, the Yankees beat the Red Sox in a 1-game Playoff for the Division title, known as the Bucky Dent Game or the Boston Tie Party. Two weeks later, on October 16, a new Pope was elected, who honored his 3 predecessors by taking the name John Paul II. The following night, the Yankees won the World Series.

*

Over this past weekend, the Yankees took 3 out of 4 against the Tampa Rays, for the 1st time playing them at their own Spring Training home, George M. Steinbrenner Field in Tampa, due to the hurricane-caused damage to the Rays' usual home, Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg. It should have been a 4-game sweep, but, unlike the way the Pope is said to be in matters of faith, the Yankees proved they were fallible.

Will Warren started on Thursday night, because 3 of the Yankees' starting pitchers -- Gerrit Cole, Luis Gil and Marcus Stroman -- were all injured, and somebody had to be the 5th starter. In the bottom of the 2nd inning, with him having gotten 5 outs, but allowed a run on 4 hits and 2 walks, manager Aaron Boone decided not to take any chances, and took him out. Ryan Yarbrough got out of the inning, then allowed a 2-run homer in the next inning.

After that, though, the Yankee bullpen -- Yarbrough, Tim Hill, Ian Hamilton and Devin Williams -- allowed 6 hits and a walk, but no runs. Ben Rice went 4-for-5 with 2 RBIs, Oswaldo Cabrera hit a home run, and the Yankees won, 6-3. Hill was named the winning pitcher.

*

Carlos Rodón started on Friday night. He needed a good one, after 3 straight bad, losing starts. He came up with one, going 6 innings, allowing 2 hits and 4 walks, striking out 9. Mark Leiter Jr., Fernando Cruz and Luke Weaver were nearly perfect the rest of the way, allowing just 1 hit and no walks between them, completing a 3-hit shutout.

The Yankees themselves only got 5 hits, but Paul Goldschmidt got 3 of them. He led off the top of the 2nd with a single. J.C. Escarra drew a walk, and Trent Grisham singled Goldschmidt home. A 1-0 lead is nerve-wracking enough in soccer, but in baseball? At least it wasn't at Fenway Park. The Yankees hung on to win.

*

The Saturday game was good in the middle. Not at the beginning, and not at the end. Carlos Carrasco, also starting to fill a hole in the rotation, allowed 4 run in 4 innings. But the bullpen did well: Hamilton pitched a scoreless 5th and 6th, Leiter a perfect 7, and Weaver a perfect 8th. Grisham hit a home run, and it was 8-4 Yankees going to the bottom of the 9th.

Based on his statistics through last season, Devin Williams looked like a great pickup for the Yankees. But he went into Aroldis Chapman mode on Saturday afternoon, and not for the 1st time. In the bottom of the 9th, he started with a groundout, then allowed single, walk, ground-rule double, single stolen base and single, for 4 runs and a tie ballgame, 8-8.

Come extra innings, and the "ghost runner" reared its head. But the Yankees could only get theirs, Anthony Volpe, to 3rd base. In the bottom of the 10th, with Christopher Morel on 2nd base, Jonathan Aranda hit one out to win the game for the Rays, 10-8.

Don't blame the pitcher, Yoendrys Gómez. It was Williams that the game didn't end after 9 innings.

*

The Sunday game was weird. How weird was it? It was Schrödinger's no-hitter: Max Fried was pitching a no-hitter, and yet, at the same time, he wasn't. Huh?

In the bottom of the 1st inning, Fried got Yandy Díaz to fly out. Then Junior Caminero grounded to 3rd base, and Oswaldo Cabrera made a bad throw. At first, he was ruled out at 1st base. Rays manager Kevin Cash appealed for instant replay, and the call was overturned: Caminero was safe. At the time, the play was ruled an error. Then, Fried walked Aranda, before getting Morel to ground into a double play to get out of the jam.

Fried then cruised. In the 4th, Cabrera made another error, allowing Morel to reach 1st, but Fried stranded him. In the 5th, he walked Danny Jansen, but got a double play. In the 7th, he hit Danny Jansen with a pitch. The no-hitter was on, with 6 outs to go.

And then, in the middle of the game, the official scorer, Bill Mathews, changed the 1st-inning error to a hit. He said he'd looked at the replay a few times, and decided that Caminero would have made it to 1st base even if Cabrera had made a good throw. In hindsight, he was probably right.

If he had ruled the play a hit immediately, no one would have cared. If he had waiting until Fried actually allowed a hit -- if he had -- and turned a one-hitter into a two-hitter, I wouldn't have had a problem with it. But he changed a game from a no-hitter to a one-hitter, without the pitcher having thrown a pitch. That's wrong, and he should be ashamed of himself.

And then, to begin the top of the 8th, Aaron Judge hit a long drive down the left-field line. It was ruled a foul ball. Boone appealed for instant replay. The replay clearly showed that the ball was fair, and it should have been ruled a home run. The umpires flat-out lied, and said it was foul. And Judge went on to strike out. They robbed him of a home run.

And it was only 3-0: The Yankees had gotten solo home runs from Grisham, Cody Bellinger, and an RBI groundout by Bellinger. The game was still very much in doubt. And the umpires blatantly robbed the Yankees of a run.

To start the bottom of the 8th, Fried allowed a single to Jake Mangum. Then he got 2 outs. And then, Boone took him out. That made no sense, especially since reliever Fernando Cruz walked the next batter. But he got the last out. He walked the 1st 2 batters in the 9th, but got out of it. Austin Wells added a solo homer, and the Yankees won the game, 4-0.

*

So the Yankees had won on Easter Sunday, to complete a 3-out-of-4 series, and have now won 6 of their last 7. They are 14-8, and lead the Toronto Blue Jays and the Red Sox by 2 games each in the American League Eastern Division. They lead the Orioles by 4 1/2, and the Rays by 5. In the loss column, the Yanks lead the Jays by 2, the BoSox by 3, the O's but 4, and the Rays by 5. They move on to Cleveland to face the Guardians.

And Pope Francis, formerly Jorge Mario Bergoglio, died this morning, at the age of 88. He had been Pope since 2013. A son of Italian immigrants to Argentina, he grew up as a fan of San Lorenzo, a soccer team in his hometown, the capital of Bueno Aires.

He is also the 1st Pope in 60 years -- aside from the brief, tragic John Paul I -- who did not deliver a Papal Mass at Yankee Stadium. Paul VI did so in 1965, John Paul II in 1979, and Benedict XVI in 2008. Each time, the New York branch of the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic fraternal organization in America, donated a plaque commemorating the event, to hang in Monument Park. Each of these plaques was moved from the old Stadium to the new one in 2009. While Francis did visit America, he did not deliver a Mass at the new Yankee Stadium.

He acted as if a Pope wasn't just supposed to speak about Christian ideals, he was supposed to carry them out, as best he can. He had been ill lately, hospitalized with bronchitis and pneumonia. He was released in time for Easter, the holiest day on the Christian calendar. I love the way he went out: Spending one last Easter with his people, and, through the surrogate JD Vance, telling Donald Trump off.