November 20, 1982, 40 years ago: The University of California and Stanford University play their annual rivalry, known simply as "The Big Game." It becomes the most talked-about game in the history of what's now known as the Pacific-Twelve Conference.

The schools are on opposite sides of San Francisco Bay. The school known as "Cal" for sports purposes and "Berkeley" for just about everything else, is the centerpiece of a great State university system, and is located in "The East Bay" part of "The Bay Area," north of Oakland. Stanford, or "The Farm" to insiders, is in Palo Alto, on The Peninsula between San Francisco and San Jose.

The rivalry between Cal and Stanford is the original version of the downstate rivalry between the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) and the University of Southern California (USC): A state school theoretically open to anyone against a stuffy prep school that is nonetheless more successful in football.

"The Big Game" was first played in 1892, and was played in San Francisco every year until 1903. It wasn't played during either World War, but has been played every year since 1946, in Palo Alto in odd-numbered years and in Berkeley in even-numbered years.

There is a trophy for the winner: The Stanford Axe. This trophy originated on April 13, 1899, during what we would now call a pep rally prior to the Stanford-Cal baseball game that was to be played 2 days later. At the time, study of the classics, including ancient Greece, was considered a must in college, and the "yell leaders" would have known Aristophanes' play The Frogs, which has a chorus of, in the original Greek, "Brekekekex, koax, koax." So they made up a literal straw man, dressed in blue and gold ribbons for Cal's colors, and chanted:

Give 'em the axe, the axe, the axe!

Give 'em the axe, the axe, the axe!

Give 'em the axe, the axe, the axe!

Give 'em the axe, where?

Right in the neck, the neck, the neck!

Right in the neck, the neck, the neck!

Right in the neck, the neck, the neck!

Right in the neck, there!

And you thought this was the Age of Innocence. The axe was taken to the baseball game, in San Francisco, but Cal won it, and a group of their students took the axe and ran off with it, and got chased by Stanford students. At some point, the handle broke off, and only the blade and the top of the handle remained. But the Cal students safely boarded the ferry back to Alameda with it.

Cal had the axe blade kept in a Berkeley bank vault, and only brought it out, via armored car, for football and baseball pep rallies. It took until April 3, 1930 for Stanford students to steal it back, thanks to a smoke bomb lobbed at a baseball pep rally at the Greek Theatre in Berkeley. Three separate cars took off, so the Cal fans wouldn't know which car had the axe. They got back to Palo Alto with it, and those students became known as the Immortal 21 -- or, in the East Bay, the Immoral 21.

After keeping it in a bank vault of their own in Palo Alto, in 1933 Stanford reached an agreement with Cal to make The Stanford Axe the trophy awarded after The Big Game. With 2 minutes left in regulation, the committee for the school holding it takes it to the 50-yard line of their sideline, and the holding committee for the other school goes to their 50, and this is known as The Stare Down. They wait for the final gun, and the the winning team runs to the 50 and the sideline, and takes it.

When people talk about "The Big Game," one edition always stands out: The 1982 edition, at Memorial Stadium in Berkeley. Cal came in at 6-4, and was headed to a bowl game. Despite John Elway being a senior quarterback, Stanford was just 5-5, and needed to win to go to a bowl. Each team was coached by an alumnus: Stanford by Paul Wiggin (who would be replaced by Elway's father Jack), Cal by former quarterback Joe Kapp.

With time running out, Stanford's Mark Harmon -- not the actor, although he did play college football, as a quarterback at UCLA, and was the son of Michigan Heisman Trophy winner Tommy Harmon -- kicked a field goal to make it 20-19 Stanford. There were 4 seconds on the clock, just time for 1 play. All Stanford had to do was stop Cal from scoring a touchdown on the ensuing kickoff -- or, in the event of a touchback, prevent an 80-yard bomb -- and they would win.

But Kapp, between playing for Cal and leading the Minnesota Vikings to the 1969 NFL Championship and into Super Bowl IV, had played in the Canadian Football League. He's the only man to quarterback in the Rose Bowl, the Grey Cup, and the Super Bowl. The CFL, even now, but especially back in the 1960s when Kapp played, still had elements of rugby to it. The forward pass is illegal in rugby, so there's a lot of laterals: Backward and sideways passes.

Figuring a squib kick would get the Stanford players to the Cal return man sooner, Harmon made a short kick. The ball got to the Cal 45-yard line, where Kevin Moen picked it up. He lateraled to Richard Rodgers (no relation to later Cal star Aaron), who gained just 1 yard. He lateraled to Dwight Garner, who gained 5 yards. He lateraled back to Rodgers.

To this day, Stanford fans claim that Garner's knee touched the ground, thus ending the game. Certainly, the Stanford band thought so, and, 144 members strong, they came onto the field -- which they shouldn't have done, since it wasn't a home game for them.

But, as in any sport where there's a clock, you have to play to the whistle. Stanford didn't, and Cal did. Rodgers got to the Stanford 45 before he faced any more Stanford players. He lateraled to Mariet Ford. By this point, the Stanford Band was 20 yards deep on the south side of the field. He got to the Stanford 27, and 3 defenders caught up with him. All he could do was throw the ball over his shoulder, a risky if legal maneuver. Moen, who started it all, caught it, and he outran 2 players, and got into the end zone. He spiked the ball, landing on Stanford trombone player Gary Tyrrell.

Stanford fans not only argue that Garner was down, but that at least one of the laterals was actually a forward pass, which should have negated the touchdown and clinched the win for Stanford.

Give 'em the axe, the axe, the axe!

Give 'em the axe, the axe, the axe!

Give 'em the axe, the axe, the axe!

Give 'em the axe, where?

Right in the neck, the neck, the neck!

Right in the neck, the neck, the neck!

Right in the neck, the neck, the neck!

Right in the neck, there!

And you thought this was the Age of Innocence. The axe was taken to the baseball game, in San Francisco, but Cal won it, and a group of their students took the axe and ran off with it, and got chased by Stanford students. At some point, the handle broke off, and only the blade and the top of the handle remained. But the Cal students safely boarded the ferry back to Alameda with it.

Cal had the axe blade kept in a Berkeley bank vault, and only brought it out, via armored car, for football and baseball pep rallies. It took until April 3, 1930 for Stanford students to steal it back, thanks to a smoke bomb lobbed at a baseball pep rally at the Greek Theatre in Berkeley. Three separate cars took off, so the Cal fans wouldn't know which car had the axe. They got back to Palo Alto with it, and those students became known as the Immortal 21 -- or, in the East Bay, the Immoral 21.

After keeping it in a bank vault of their own in Palo Alto, in 1933 Stanford reached an agreement with Cal to make The Stanford Axe the trophy awarded after The Big Game. With 2 minutes left in regulation, the committee for the school holding it takes it to the 50-yard line of their sideline, and the holding committee for the other school goes to their 50, and this is known as The Stare Down. They wait for the final gun, and the the winning team runs to the 50 and the sideline, and takes it.

When people talk about "The Big Game," one edition always stands out: The 1982 edition, at Memorial Stadium in Berkeley. Cal came in at 6-4, and was headed to a bowl game. Despite John Elway being a senior quarterback, Stanford was just 5-5, and needed to win to go to a bowl. Each team was coached by an alumnus: Stanford by Paul Wiggin (who would be replaced by Elway's father Jack), Cal by former quarterback Joe Kapp.

With time running out, Stanford's Mark Harmon -- not the actor, although he did play college football, as a quarterback at UCLA, and was the son of Michigan Heisman Trophy winner Tommy Harmon -- kicked a field goal to make it 20-19 Stanford. There were 4 seconds on the clock, just time for 1 play. All Stanford had to do was stop Cal from scoring a touchdown on the ensuing kickoff -- or, in the event of a touchback, prevent an 80-yard bomb -- and they would win.

But Kapp, between playing for Cal and leading the Minnesota Vikings to the 1969 NFL Championship and into Super Bowl IV, had played in the Canadian Football League. He's the only man to quarterback in the Rose Bowl, the Grey Cup, and the Super Bowl. The CFL, even now, but especially back in the 1960s when Kapp played, still had elements of rugby to it. The forward pass is illegal in rugby, so there's a lot of laterals: Backward and sideways passes.

Figuring a squib kick would get the Stanford players to the Cal return man sooner, Harmon made a short kick. The ball got to the Cal 45-yard line, where Kevin Moen picked it up. He lateraled to Richard Rodgers (no relation to later Cal star Aaron), who gained just 1 yard. He lateraled to Dwight Garner, who gained 5 yards. He lateraled back to Rodgers.

To this day, Stanford fans claim that Garner's knee touched the ground, thus ending the game. Certainly, the Stanford band thought so, and, 144 members strong, they came onto the field -- which they shouldn't have done, since it wasn't a home game for them.

But, as in any sport where there's a clock, you have to play to the whistle. Stanford didn't, and Cal did. Rodgers got to the Stanford 45 before he faced any more Stanford players. He lateraled to Mariet Ford. By this point, the Stanford Band was 20 yards deep on the south side of the field. He got to the Stanford 27, and 3 defenders caught up with him. All he could do was throw the ball over his shoulder, a risky if legal maneuver. Moen, who started it all, caught it, and he outran 2 players, and got into the end zone. He spiked the ball, landing on Stanford trombone player Gary Tyrrell.

Stanford fans not only argue that Garner was down, but that at least one of the laterals was actually a forward pass, which should have negated the touchdown and clinched the win for Stanford.

Even if either one of these statements had been true, the Stanford Band being on the field was interference, and neither half can end on a defensive penalty. At the least, Cal would have been given another chance to try and score. At the most, the referee could have awarded Cal the touchdown anyway, as happened with the Tommy Lewis/Dickie Moegle incident at the 1954 Cotton Bowl.

At any rate, the touchdown was awarded. Final score: California 25, Stanford 20. No bowl for Stanford. No Heisman for Elway. (It went to Herschel Walker of Georgia instead.) "The Play" became instant legend.

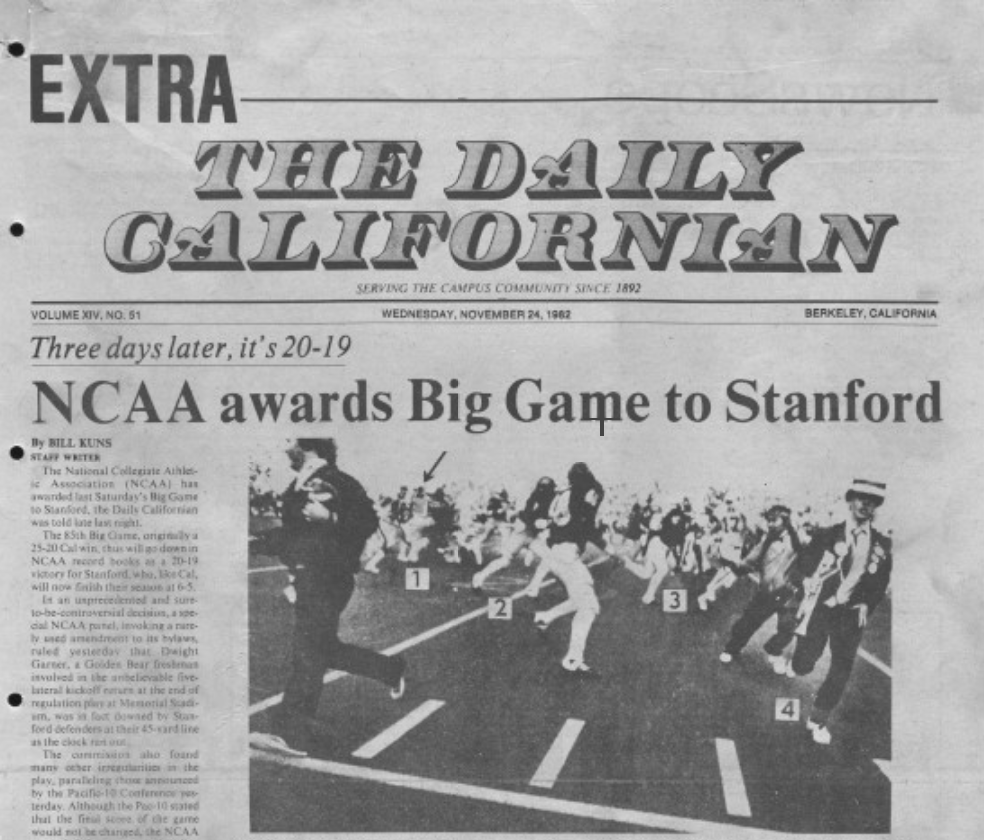

But Stanford students, already known for their practical jokes, had one last card to play. The Stanford Daily, the student newspaper, printed up 7,000 bogus copies of the opposition's student newspaper,

The Daily Californian, and distributed them 3 days after the game, with a lead article claiming that the NCAA had overruled the touchdown and awarded Stanford the victory. Today, with social media, the headline would have been quickly exposed as bogus. At the time, though, it upset a lot of people in Berkeley, until the NCAA released a statement saying the result would stand.

At any rate, the touchdown was awarded. Final score: California 25, Stanford 20. No bowl for Stanford. No Heisman for Elway. (It went to Herschel Walker of Georgia instead.) "The Play" became instant legend.

But Stanford students, already known for their practical jokes, had one last card to play. The Stanford Daily, the student newspaper, printed up 7,000 bogus copies of the opposition's student newspaper,

The Daily Californian, and distributed them 3 days after the game, with a lead article claiming that the NCAA had overruled the touchdown and awarded Stanford the victory. Today, with social media, the headline would have been quickly exposed as bogus. At the time, though, it upset a lot of people in Berkeley, until the NCAA released a statement saying the result would stand.

"Fake News"

Officially, Stanford leads the rivalry 65-47-11, having won 10 of the last 11 games. Since the institution of the Axe as a trophy, Stanford leads 48-34-3.

I say, "Officially," because whenever Stanford holds the trophy, they replace the plaque containing the 1982 result so that it reads "California 19, Stanford 20." But the agreed-upon rules state that, before the game, it must be changed back to "California 25, Stanford 20" no matter what.

No comments:

Post a Comment