He was lucky to have played at all -- or even to have lived into that era. Incredibly, he lived into this week.

Leland Victor Brissie -- I can't find any record of why he was called "Lou" and not "Lee," like Hall-of-Famer Leland Stanford MacPhail Jr. -- was born June 5, 1924 in Anderson, South Carolina, and grew up in nearby Ware Shoals. His time at Presbyterian College in Clinton, South Carolina was cut short when World War II led him to enlist in the U.S. Army.

My grandmother was born the day before he was, 750 miles to the northeast in Brooklyn. Her husband, my grandfather, served in the Army in the campaign to liberate Italy. So did Brissie. Unlike Grandpa, however, Brissie was in combat. On December 7, 1944, 3 years to the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought America into The War, he and his platoon were in the Apennine Mountains in the north of the country, when the Germans attacked. A shell exploded next time him, shattering the shinbone of his left leg.

Brissie, 6-foot-4 and listed at 210 pounds in his playing days, was a lefthanded pitcher. This meant that, in his windup, while he kicked his right leg up, his left leg supported all of those 210 pounds. Now, that leg was ruined: Not only was the shin in more than 30 pieces, but an infection had set in. Brissie recalled, "My leg had been split open like a ripe watermelon." And the surgeon at the Army hospital in Naples, Dr. Wilbur Brubaker, told him that amputation would probably be necessary.

Brissie pleaded with Brubaker to try to save the leg, explaining that he was a baseball player. At this time, penicillin was still in its early days of treating infections -- the words "wonder drug" were still used. Over the next 2 years, Brissie was operated on 23 times.

While this was going on, he wrote to Connie Mack, owner and manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, the club that had been scouting him before The War. Mack told him a tryout would be waiting for him.

In the Spring of 1947, as the Brooklyn Dodgers were preparing Jackie Robinson for the reintegration of Major League Baseball, Brissie reported to the A's training camp in West Palm Beach, Florida, to begin his own "great experiment." He was assigned to their farm team in Savannah, Georgia. He had been given a metal brace to protect his leg from line drive comebackers. He went 23-5. That showed Mack, "the Grand Old Man of Baseball," what he needed to know.

September 28, 1947 was an amazing day in baseball. It was the last day of an epic regular season, with an epic Yankee-Dodger World Series to come. The Dodgers, including Robinson, were celebrating the winning of the National League Pennant.

The St. Louis Browns started Dizzy Dean, who'd been retired for 6 years due to an injury and was broadcasting for the Browns, and, frustrated with their pitching, said, on the air, "Doggone it, I can pitch better than 9 out of the 10 guys on this staff." The Brown pitchers' wives complained to management, and since Dean was still only 37, they chose the last day of the season (when the spectator-poor Browns would have even more trouble than usual filling Sportsman's Park) to have Dean pitch for the Browns. He went 4 innings, and got a hit -- but pulled a muscle rounding 1st base, and had to leave the game. The Browns' bullpen proved Ol Diz' point as much as he did, losing the game for him.

And at Yankee Stadium, the American League Champion Yankees hosted the A's, in front of 23,085 fans -- not a bad total for a meaningless game. Bill Wight -- not to be confused with later NL 1st baseman, Yankee broadcaster and NL President Bill White -- started for the Yankees, in what turned out to be the last of the 15 games he pitched for them. Starting for the A's was Lou Brissie, wearing Number 17. (He switched to 19 the next season, and wore that for most of his career.) The man who could easily have been killed, and nearly lost his leg, was pitching in the major leagues -- at Yankee Stadium, no less.

Perhaps the appropriate analogy is to the dog seen walking on its hind legs: "It was not done well, but you were surprised to have seen it done at all." Brissie went 7 innings, and allowed 5 runs on 9 hits and 5 walks. He was tagged with the loss. Wight went the distance, and the Yankees won, 5-3. (Wight died in 2007, and despite pitching for a World Series winner that year, is not generally remembered today.)

Included in that Yankee win was a home run by Johnny Lindell, 2 hits each by Phil Rizzuto, Tommy Henrich and George McQuinn, and 1 each by Joe DiMaggio and rookie catcher Yogi Berra. So it's not like Brissie was facing a bad team, or even a good one letting a bunch of rookies get their end-of-season cup-of-coffee against the opposition's prospects. No, Brissie didn't pitch well -- but he pitched in the major leagues, which is more than nearly everyone reading this will ever do, and an astounding achievement considering where he was nearly 3 years earlier.

Yogi, A's 1st baseman Dick Adams, and Carl Scheib are now the only surviving players from this inspirational game. Scheib was a decent-hitting pitcher: The next season, 1948, he went 31-for-104, for a .298 average. Mack sent him up to pinch-hit for Brissie in the top of the 8th (he didn't reach base) -- but not, oddly, to the mound to pitch the bottom of the 8th. Instead, Mack sent Joe Coleman, whose son Joe and grandson Casey also appeared in the majors. (UPDATE: Scheib would be the last survivor, living until March 24, 2018.)

His next game was the next season's opener. In those days, rather than play a single game at 11:05 AM on Patriots' Day -- the 3rd Monday in April, commemorating the Battle of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775 -- so that the Fenway Park crowds can get out before they interfere with the runners of the Boston Marathon, the Sox played a doubleheader. And on April 19, 1948, the Sox hosted the A's. The A's won the 1st game, 5-4 in 11 innings. Mack sent Brissie out to start the 2nd game.

This was the late-1940s Red Sox that Brissie was facing: Ted Williams, Vern Stephens, Joe's brother Dom DiMaggio, Johnny Pesky, Bobby Doerr. An all-time great, a great slugger for a shortstop (especially in that era), and 3 very good contact hitters. This would be no easy assignment, especially in the little pinball machine off Kenmore Square.

Williams came up. He was a notorious pull hitter who inspired Cleveland Indians shortstop-manger Lou Boudreau -- who would almost singlehandedly beat the Sox in a one-game Playoff for the Pennant in October -- to invent the infield shift on lefthanders so often used today on players like David Ortiz, Jason Giambi and Mark Teixeira.

This time, the Splendid Splinter hit a rocket right back at Brissie, caroming off the plate covering his scarred shin. The clang of horsehide on steel could be heard all over Fenway. Naturally, Brissie went down.

Ted, himself a World War II veteran (and later to be a Korean War veteran), told the story in his memoir My Turn at Bat:

I hit a ball back to the box, a real shot, whack, like a rifle clap. Down he goes, and everybody rushes out there, and I go over from first base with this awful feeling I've really hurt him. Here's this war hero, pitching a great game. He sees me in the crowd, looking down at him, my face like a haunt. He says, "For chrissakes, Williams, pull the damn ball."

Brissie was all right. He got up, went the distance, allowed 2 runs on 4 hits and 1 walk, struck out 7, outpitched Denny Galehouse, and even singled home 2 runs off Galehouse. The A's won, 4-2.

No A's players survive from this game. From the Red Sox, surviving are 2nd baseman Doerr, now the oldest living member of the Hall of Fame; and right fielder Sam Mele, a Queens native, best remembered for managing the Minnesota Twins to their 1st Pennant in 1965. (UPDATE: Mele died in 2017, Doerr 6 months later.)

Brissie went 14-10 that year, and improved to 16-11 in 1949, being named to the AL All-Star Team and pitching 3 innings in the All-Star Game, held that year in New York, at Brooklyn's Ebbets Field.

He was traded to the Indians in 1951, part of a 3-way deal that also involved the Chicago White Sox, including the Indians sending Minnie Minoso to become the 1st black player to play for either Chicago team. Brissie was used mostly in relief in Cleveland, and he retired following the 1953 season, finishing 44-48. He then went into business back in South Carolina, and directed the American Legion baseball program.

In the last few years, Brissie was the subject of a biography by New York Times sportswriter Ira Berkow, The Corporal Was a Pitcher. And he always visited Veterans Administration hospitals to talk to war veterans -- Korea in the 1950s, Vietnam in the 1960s and '70s, the Persian Gulf in the 1990s, and Iraq and Afghanistan these last few years.

"I knew I was a symbol to many veterans trying to overcome problems," he once said. "I wasn't going to let them down... People with disabilities have told me, 'Because of you, I decided to try.' That changes you."

But long after his wound, his leg remained prone to infections, and while he was otherwise healthy in his last few years, he began to use crutches to get around. He was admitted to a VA hospital earlier this year, in Augusta, Georgia, not far from his home -- not to visit wounded veterans but to be treated as one. He died this past Monday, at the age of 89.

He was married twice, and is survived by his 2nd wife, 2 daughters, 2 stepchildren, and their children and grandchildren.

Lou Brissie appeared in 234 major league games -- 234 more than I ever would. But as a baseball fan who's had problems with his own legs (not through war, and not nearly to the same extent), he was an inspiration to me.

*

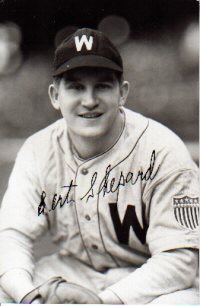

So was Bert Shepard (1920-2008), also a lefthanded pitcher. He wasn't as lucky as Brissie: He was a pilot, shot down by the Nazis, and recovered alive by a German Army doctor. Since Bert was unconscious, and unable to plead for the saving of his leg, the German doctor amputated it below the knee.

But Bert, too, was determined to make it to the majors. He did, for 1 game, on August 4, 1945, wearing Number 34 and a prosthesis, pitching the last 5 1/3rd innings of a game for the Washington Senators against the Red Sox at Griffith Stadium in Washington.

The game was already out of hand when he was sent in: The Red Sox won, 15-4. Bert allowed 1 run on 3 hits and 1 walk, and never appeared in another game. He did, however, continue as an athlete, winning competitions for amputees in both running and golf, even in his 70s.

The game was notable for 2 other reasons. Bert relieved Joe Cleary, who was another player who was only playing due to The War's manpower drain. It was his only big-league appearance as well, and he only got 1 batter out, allowing 7 runs on 5 hits and 3 walks. There are pitchers who allowed baserunners and didn't get anybody out, thus having an earned run average of infinity. Cleary has the highest career ERA of anybody who did actually get someone out: 189.00.

The other reason is that Tom McBride of the Red Sox tied a major league record for most RBIs in an inning: 6, in the 4th, all off Cleary.

Bert wasn't bitter about his amputation: In 1993, This Week In Baseball did a piece on him, 50 years after the fact, and followed him back to Germany where he saw the doctor again, and thanked him for saving his life, and (if only for 1 game) his baseball career.

Surviving from Shepard's lone appearance in the majors are Senators center fielder José Zardón and opposing pitcher Dave "Boo" Ferris. (UPDATE: Ferris died in 2016, Zardón the following year.)

UPDATE: Lou Brissie is buried at Pineview Memorial Gardens in North Augusta, South Carolina. Bert Shepard is buried at Riverside National Cemetery in the Los Angeles suburb of Riverside, California.

No comments:

Post a Comment