Today is the anniversary of the major league debut of Jackie Robinson. On April 15, 1947, he played 1st base for the Brooklyn Dodgers in their home opener at Ebbets Field. Although he did not get a hit, he did reach base on an error, scored a run, and played errorless ball in the field. The Dodgers beat the Boston Braves, 5-3.

Yes, kiddies, a Major League Baseball team in Brooklyn, and a National League team in Boston. There was also an American League team in Philadelphia and another in St. Louis. And, for 60 years until Jackie arrived, there were no black players, and no Hispanic players who looked anything less than all-white.

There was also no artificial turf, no domed stadiums (retractable or otherwise), no fireworks-shooting scoreboards, and, until the next year, no teams had regular television broadcasts. In fact, it wasn't until Game 1 of that year's World Series that a Series game had been on TV.

September 30, 1947. That's another day that should be celebrated. You see, Jackie said that was the highlight of his career. It meant that he made it.

Yes, I know, he titled his autobiography I Never Had It Made. And if he were alive today (diabetes and heart trouble killed him at 53), he'd be the first to tell us that getting into a game, getting into a World Series game, playing for a World Champion in 1955, getting into the Hall of Fame, getting so many men of his race into the game, opening the door for Hispanic players and now Asian players... he'd tell us that it's still not enough.

But on that day, at Game 1 of the World Series, standing there on the foul line, hearing the National Anthem, knowing that he was on that line with his Dodger teammates, looking across at the opposing Pinstripers, at Yankee Stadium, preparing to play for the championship of the baseball world, it meant that he, and his teammates, had faced all the pressure, all the bigotry, all the questions, and had not only lasted, but thrived. It was victory on the field of play, and it was victory in the larger field called life.

*

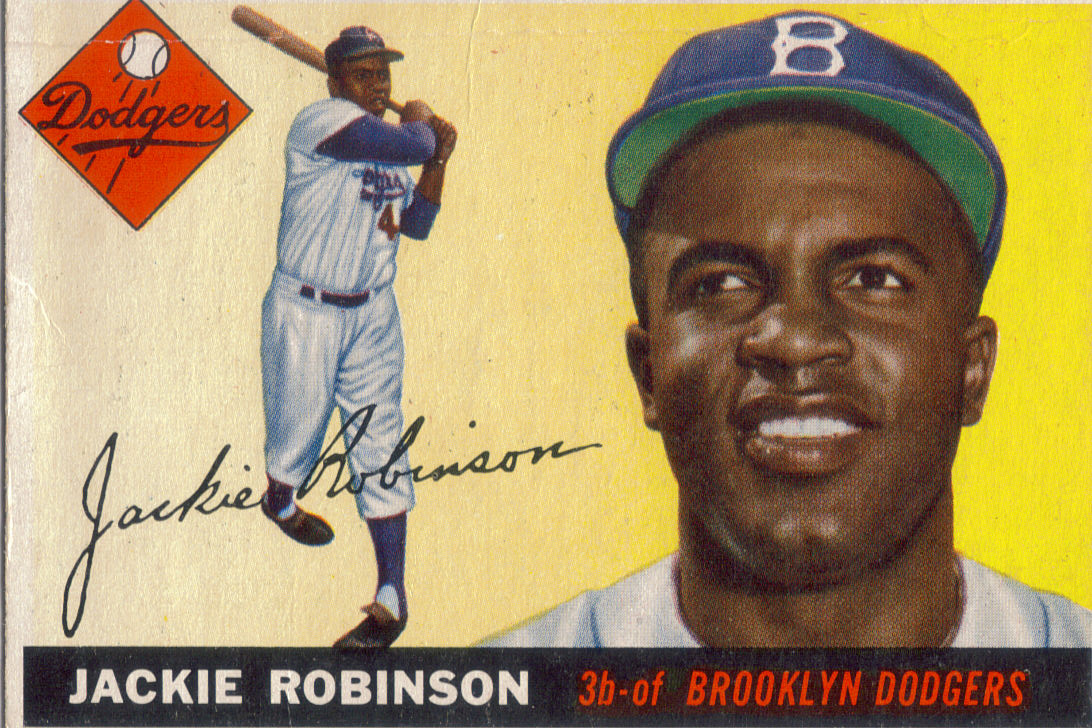

So much has been made of Jackie Robinson the pioneer, and rightly so. But Jackie Robinson the player has often been overlooked. As Thomas Jefferson said in the Declaration of Independence, Let the facts be submitted to a candid world:

He was a good hitter: A lifetime batting average of .311, on-base .409, slugging .474, his OPS+ a strong 132 (meaning that his combined on-base and slugging percentage was 32 percent better than that of the average player), and only once in his 10 seasons (ironically, in 1955, the one year his team went all the way) did he have an OPS+ of less than 100, otherwise going from 107 to a peak of 154.

He never hit 20 home runs in a season (twice reaching 19 despite playing in Ebbets Field, a bandbox), and only once had more than 95 RBIs. But in 6 of his first 7 seasons (all but 1952), he had at least 30 doubles. And in 6 of his first 7 (all but 1950), he scored at least 100 runs and had at least 20 stolen bases.

This is the key to understanding Jackie's impact: Baserunning. My grandmother was from Queens and was a huge Dodger fan. Her all-time hero in baseball, and in life, was Jackie Robinson. She couldn't stop talking about him, especially his baserunning.

He'd dance off 1st, driving pitchers nuts. He'd steal 2nd, or unnerve them into a balk. Then he'd do one or the other to get to 3rd. Vin Scully, the voice of the Dodgers since 1950 and the last continuous link to their Brooklyn days, said he once saw Jackie get a hit, and then get the pitcher so nervous that he walked the next batter, sending Jackie to 2nd; watched Jackie jumping off 2nd, suggesting he might steal 3rd, and in his nervousness walked the next batter to load the bases; and then, knowing how often Jackie had stolen home plate -- it became his trademark, one that lasts to this day -- was so shaky that he walked the next batter to force in the run, and Jackie then calmly walked to the plate. Scully's been broadcasting for 59 seasons now, and he says he's never seen anybody else do that.

Jackie Robinson made baserunning -- not just the stolen base, but taking the extra base, or even the threat of the stolen or extra base -- a major weapon for the first time since Babe Ruth made baseball a homer-happy game. He changed how the game was played, not just by whom.

After him came the other aggressive black players like Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Frank Robinson. After them came the "Go-Go White Sox" of Luis Aparicio and Nellie Fox -- one of the first true Hispanic stars, and a white Southerner who knew he wasn't big and strong, so he adapted his game so that he played it like the black stars. After that came Maury Wills, and then Lou Brock, and soon every team decided it needed a running game.

Jackie also won the 1st officially-awarded Rookie of the Year award, in 1947, and the National League's Most Valuable Player award in 1949. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1962, on the first ballot.

He went in with Bob Feller, the great Cleveland Indians pitcher, who also went in on the first ballot. They were the first players so honored since the first inductions in 1936. Feller had once said that, if he were white, with his qualifications and physical attributes -- Jackie was built like a football running back, which he was, and a very good one, at UCLA in 1939 and '40 -- he wouldn't even be considered "big league material." Feller has had to spend many an occasion over the last 60 years eating those words, and he now says he was proud to go into the Hall with Jackie.

Jackie collected 1,518 hits -- in just 10 seasons. And remember, he played from age 28 to age 37. He only had half a career. Even his "prime" was cut in half. Had baseball always been open to nonwhite players -- assuming he even would have played baseball, rather than football, or gone into another line of work had American race relations been better to the point where the Jackie Robinson we know hadn't been necessary -- he could have played a full career, 18 to 20 seasons, and gotten to 3,000 hits.

Would he be in the Hall of Fame, with the stats he actually had, if he were white, or if another man were the first black player since the 1880s? Maybe: He had some terrific seasons, won that MVP award, and in 8 of his 10 seasons, his team got to the last game of the season still eligible for the Pennant. He won 6 Pennants, but only the 1 World Series, as the 1949-56 Dodgers were one of the unluckiest teams in baseball history.

One of the great ironies of baseball is that many people credit Jackie's steal of home in Game 1 as the spark that led the Dodgers to finally beat the Yankees and finally win a World Series in 1955. But the Dodgers lost that game, and lost Game 2 as well. They then won 4 of the last 5, the first team ever to win a World Series after being down 2 games to none. Jackie's steal was a highlight, but it had very little to do with the Dodgers finally slaying the Pinstriped dragon. They won because they got great pitching from Johnny Podres and Clem Labine, 4 homers from Duke Snider, 2 more from Roy Campanella, key hits from the previously October-struggling Gil Hodges, and the benefit of Mickey Mantle being hurt and unable to contribute to the Yankees.

*

In March 1997, I won a radio contest, and got two tickets to the April 15 game at Shea Stadium between the Mets and the now-Los Angeles Dodgers. It was going to be Jackie Robinson Night, the 50th Anniversary of Jackie's debut. Naturally, I took my grandmother.

Rachel Robinson was there. So was President Bill Clinton. So was Commissioner Bud Selig, who announced that the Number 42 that Jackie wore for the Dodgers was being retired for all of baseball, with everyone still wearing it allowed to keep it until they retired. (Mariano Rivera of the Yankees is now the last one to do so.) Several of Jackie's surviving teammates were there, including Snider, Don Newcombe and Carl Erskine. I noticed that Pee Wee Reese wasn't there: He was battling cancer, and he died 2 years later.

On line for a hot dog later on, I saw one of the TVs showing a guy in the stands, who looked awfully familiar, but I couldn't quite recognize him. Maybe it was because he was older than I was used to seeing him in photographs. Maybe it was because he was wearing a Mets cap. Then he was identified as Sandy Koufax, whose first 2 years (1955 and '56) were Jackie's last 2. (Apparently, Koufax and the Dodger brass were at loggerheads at the time, and he was a high school classmate of Met owner Fred Wilpon's, thus willing to wear the Met cap.)

The Mets won the game, 5-2, and Grandma and I left Shea through Gate C, near the players' and press entrance. At one point we heard something, and turned around, and the Robinson family was leaving. Grandma was thrilled that she got that close to Rachel, who still heads the Jackie Robinson Foundation, now run by daughter Sharon.

It was the last major league game my grandmother ever went to. Although the Lakewood BlueClaws, a Single-A farm club of the Phillies, soon took up shop just 6 miles from her house, and she saw a few of their games, she never again schlepped up to New York, Philadelphia or anywhere else.

She would be pleased to know that she has a great-grandchild named Rachel, although my sister named her that for reasons that have nothing to do with baseball. (Update: Now that Ashley and Rachel are old enough to understand some of the things I tell them about baseball, and have learned about Jackie, they admire him, too, and Rachel likes that she shares the name with Mrs. Robinson.)

That last game, and the aftermath, was Jackie Robinson's final gift to my grandmother. But as long as baseball is played, and it's played by more than just white men, he is the gift that keeps on giving.

I just wish he'd been able to deliver it in person a while longer.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment