Timing is everything. Two days from now is the 50th Anniversary of the play that made a rookie running back into an all-time football legend. The following day, he was scheduled to be honored for the achievement. But now, he won't be available for the celebration.

Franco Harris -- no middle name -- was born on March 7, 1950, at Fort Dix, a U.S. Army base in Wrightstown, Burlington County, New Jersey. His father, Cad Harris, was a soldier stationed in Italy during World War II. While there, he met Gina Parenti, married her, and took her back to America. So, like baseball star Roy Campanella, from nearby North Philadelphia and playing in nearby Brooklyn, Franco was half-African-American, and half-Italian.

He grew up in Mount Holly, the seat of Burlington County, not far from Philadelphia, and went to Rancocas Valley Regional High School. Other RV graduates of note include former Philadelphia Eagles receiver Irving Fryar, current Eagles linebacker Shaun Bradley, and Barbara Park, author of the Junie B. Jones series of children's books.

Franco went to Pennsylvania State University, to play football for head coach Joe Paterno, as would his younger brother, safety Pete Harris. Franco was mainly a blocker for All-American running back Lydell Mitchell, but still managed to rush for 2,002 yards, catch 28 passes for 352 yards, and score 25 touchdowns.

*

He was taken with the 13th pick in the 1972 NFL Draft, by the Pittsburgh Steelers. They began play in 1933, with Art Rooney having founded them. But Art's love of football far exceeded his knowledge of it. In 1947, they finished in a 1st place tie in the NFL Eastern Division with the Philadelphia Eagles, and lost a playoff. To this day, the NFL does not recognize this as an official Playoff game.

Finally, after a 1-13 season in 1969, Art's sons, Dan and Art Jr., told dear old Dad to let them run the team from now on. And in just 3 seasons, they had built the team into AFC Central Division Champions. Coached by Chuck Noll, they had an offense led by quarterback Terry Bradshaw, and a defense known as the Steel Curtain, led by tackle "Mean" Joe Greene.

Harris was named NFL Offensive Rookie of the Year in 1972. That year, the owners of a local Italian restaurant, noting that he was half-black and half-Italian, came to Three Rivers Stadium in fatigues and battle helmets, calling themselves "Franco's Italian Army." Francisco Franco was still alive and in power in Spain when the fan club was founded, and while its members were not openly political, neither did they seem to have a problem with a name associated with fascism.

Receiver Lynn Swan, who would be drafted 2 years later, and became Harris' roommate on roadtrips, said, "When he drafted Franco Harris, he gave the offense heart, he gave it discipline, he gave it desire, he gave it the ability to win a championship in Pittsburgh."

Al Davis ran the Oakland Raiders, and had built them into AFL Champions in 1967. But they lost Super Bowl II, then lost the 1968 AFC Championship Game to the New York Jets. By 1972, they were dominating the AFC Western Division, but hadn't won a Super Bowl yet.

And so, on Saturday afternoon, December 23, 1972, Davis' Silver and Black marched into Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh to face the Rooneys' Black and Gold. For a game with such an epic ending, it was not good theater most of the way. The 1st half ended scoreless. Roy Gerela kicked a field goal early in the 2nd half, but it remained 3-0 at the end of the 3rd quarter. Gerela kicked another field goal early in the 4th quarter, but the Steelers couldn't put the ball in the end zone, so it remained 6-0 as the clock wound down.

Daryle Lamonica, known as the Mad Bomber, struggled in the 1st half, and coach John Madden replaced him with Ken Stabler, the Alabama lefthander known as the Snake. With 1:17 to go, Stabler ran for 30 yards to get into the end zone. George Blanda, the Raiders' ageless backup quarterback and regular kicker, nailed the extra point, and the Raiders had a 7-6 lead.

The Steelers did not yet have a reputation as the kind of team that could win this kind of game. And Pittsburgh fans, who had seen the Pirates win the World Series the year before, were not used to glory from their football team. The 50,327 fans inside Three Rivers figured the game was lost.

Among them was Art Rooney. "The Chief" left his suite and got into an elevator, to go down to the locker room to congratulate the Raiders and console his team. So he never saw the play that changed the course of his team's history.

Bradshaw, who had been the top pick in the 1970 NFL Draft, had a difficult relationship, not just with Noll, but with the Pittsburgh fans. He hadn't yet lived up to their hopes. Now, he had gotten the Steelers to their own 40 yard line. But it was 4th and 10, and there were only 22 seconds left, and the Steelers had no time-outs left.

Noll's intended play was "66 Circle Option," intended for Barry Pearson, a rookie who had been on the Steelers' bench all season long without being sent into a game. Now, he was -- his 1st professional play.

But just as no battle plan survives the first shot, Noll's play didn't last. Raiders Tony Cline and Horace Jones bore down on Bradshaw, and "the Blonde Bomber" from Louisiana had to scramble. He just got a throw off before getting clobbered by Cline and knocked to Three Rivers' artificial turf.

The ball got to the Raiders' 33-yard line, and it looked like Steeler running back John "Frenchy" Fuqua was going to catch it. But Raider safety Jack Tatum did what he so often did to potential receivers: He leveled Fuqua.

Big mistake: As with so many dirty soccer players, Tatum should have gone for the ball, not the opposing player. He could have intercepted it. Instead, the ball bounced off him, and went backwards to the Raider 43. And it almost hit the ground.

And for 50 years, the Raiders and their fans have insisted that the ball hit Fuqua first, which, under the rules of the time, would have made every Pittsburgh player an ineligible receiver after that. And they have insisted that the ball did hit the ground.

It didn't. Harris saved it, and took off down the left sideline, and scored. It was 3:29 PM -- don't bet any Steeler fan old enough to remember.

Steeler radio announcer Jack Fleming said, with only slight exaggeration, "From out of nowhere came Franco Harris, riding a white stallion, heading up Franco's Italian Army, galloping into the sunset!"

Like Rooney, Bradshaw didn't see the play. He remembered being down on the ground, and hearing a tremendous roar going up: "I knew that this was a good sound. This was the sound of something good happening."

Fans came pouring onto the field, and had to be cleared, because there was still an extra point to kick, which Gerela did, and 5 seconds to play. The Raiders could do nothing with the ensuing kickoff, and the Steelers had won, 13-7.

Those '72 Raiders still insist they were robbed. It would take until the 1976 season for them to win a Super Bowl. But the Steelers didn't win immediately, either: This was the season in which the Miami Dolphins went undefeated. Eight days later, they came into Three Rivers -- at the time, home-field advantage for Conference Championships was on a rotating basis, not decided by record -- and beat the Steelers, on their way to winning Super Bowl VII.

But the catch became known as "The Immaculate Reception." What Art Rooney, a devout Irish Catholic, thought about that, only he knew. Others, noting that it was 2 days to Christmas, called it a Christmas Miracle.

Along with Alan Ameche's overtime plunge to win the 1958 NFL Championship Game for the Baltimore Colts, Bart Starr's quarterback sneak to win the 1967 Championship Game (the Ice Bowl), and Dwight Clark's "The Catch" from Joe Montana to win the 1981 NFC Championship Game, it ranks as perhaps the greatest play in NFL history.

The Steelers would win Super Bowls IX, X, XIII and XIV. Harris was named the Most Valuable Player for IX, Swann for X, and Bradshaw for XIII and XIV. The Raiders would win Super Bowls XI, XV and XVIII.

"During that era, each player brought their own little piece with them to make that wonderful decade happen," Harris said during his Hall of Fame speech in 1990. "Each player had their strengths and weaknesses, each their own thinking, each their own method, just each, each had their own. But then it was amazing, it all came together, and it stayed together to forge the greatest team of all times."

*

Harris was named to the Pro Bowl in each of his 1st 9 seasons. He played for the Steelers until 1983, with 1 more season with the Seattle Seahawks. He finished his career with 12,120 rushing yards, 2nd all-time behind Jim Brown at that point. He also caught 307 passes for 2,287 yards, and retired with exactly 100 touchdowns.

He was named the NFL's Man of the Year for the 1976 season, and was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, the NFL's 1970s All-Decade Team, and the Steelers' 75th Anniversary All-Time Team and their Hall of Honor. In 1999, The Sporting News ranked him 83rd on their list of the 100 Greatest Football Players. In 2006, a statue of him catching the Immaculate Reception was unveiled on the concourse of Pittsburgh International Airport. In 2011, he was elected to the New Jersey Hall of Fame -- that's for all citizens of the State, not just great athletes. He is easily New Jersey's greatest football player ever.

Harris and former Penn State teammate Lydell Mitchell founded a food-service company, to produce nutritious school meals. They used that company to buy the Parks Sausage Company, the 1st African-American-owned business to go public. In 2008, he served as one of Pennsylvania's Presidential Electors for Barack Obama.

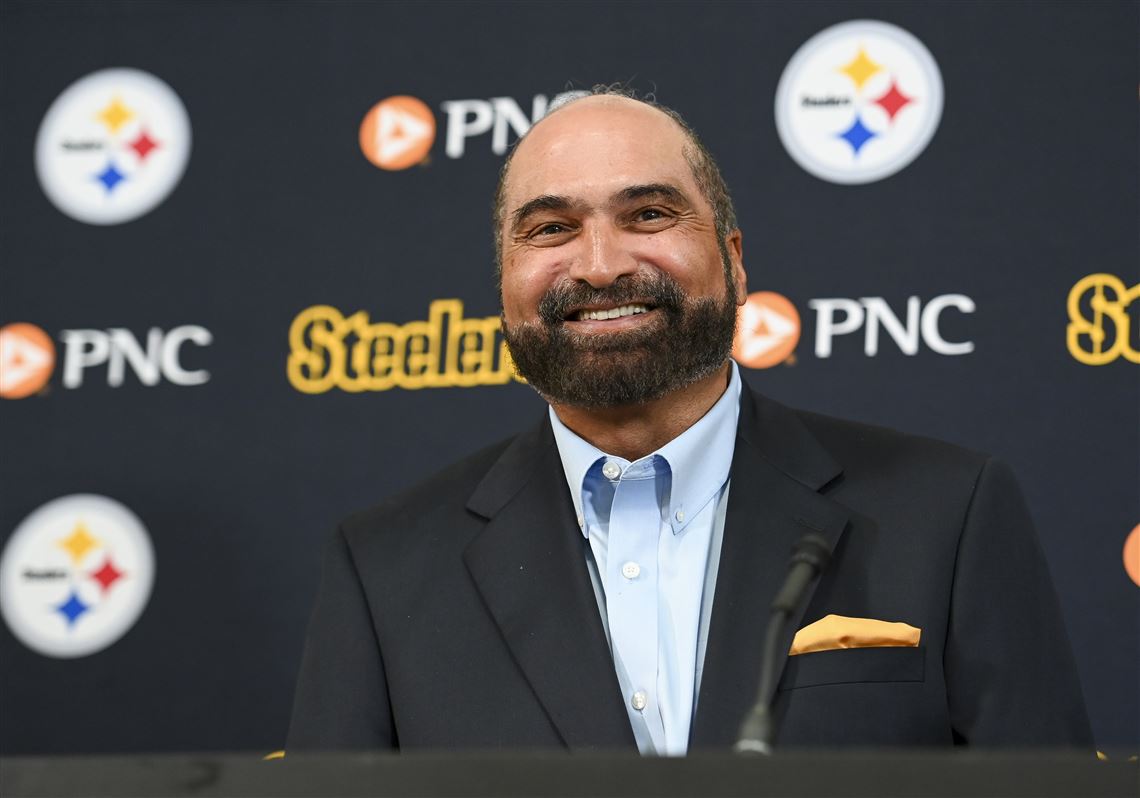

The Steelers had announced that, this coming Sunday, with the Steelers scheduled to play the now-Las Vegas Raiders on NBC Sunday Night Football on Christmas Eve, 1 day after the 50th Anniversary of the Immaculate Reception, they were going to retire Franco Harris' Number 32.

But now, he won't be able to take part in the ceremony. He died today, December 21, 2022, in a statement issued by his son Dok. He was 72. He was also survived by his wife, the former Dana Dokmanovich.

No comments:

Post a Comment