One of the greatest football players who has ever lived has died, and yet, the thing most people remember about him wasn't his playing, but his example.

Gale Eugene Sayers was born on May 30, 1943 in Wichita, Kansas, and grew up in Omaha, Nebraska. He had an older brother, Roger, who became a collegiate track star; and a younger brother, Ron, who played at running back for the San Diego Chargers.

Gale graduated from Omaha Central High School, leading them to a State Championship in 1960, and set a State record in the long jump the following Spring. Other notable Central graduates include later Green Bay Packers running back Ahman Green, acting patriarch Henry Fonda, Benson actress Inga Swenson, and Omaha Mayor and later Senator Edward Zorinsky.

Gale wanted to go to the University of Iowa, which, at the time, was more open to black players than many other Midwestern schools. But on his one campus visit, he was told that the head coach didn't have time to meet with him. So Sayers did not become a Hawkeye.

That coach was Jerry Burns: Although he joined Vince Lombardi's staff on the Green Bay Packers and helped win the 1st 2 Super Bowls, in 18 years as an assistant with the Minnesota Vikings, he went 0-4 in Super Bowls; in 6 years as an NFL head coach, all with the Vikings, he never reached a Super Bowl.

So Gale went to the University of Kansas. The team wasn't special, going just 17-12-1 with no bowl game appearances in his 3 years on the varsity -- they made it to the 1961 Bluebonnet Bowl, but freshmen weren't allowed to play varsity sports until 1972 -- but he was. All 3 seasons, he was a 1st team All-Conference selection in what was then known as the Big Eight, and a 2-time consensus All-America pick.

He became known as the Kansas Comet, finishing 3rd in the nation with 1,125 rushing yards and 1st with 7.1 yards per carry in 1962. That was as a sophomore. Sophomores generally didn't do that well in those days. In 1964, he thrilled Big Eight fans, sick of seeing the University of Oklahoma win the title seemingly every year, but returning the opening kickoff 93 yards for a touchdown in a 15-14 Kansas win. He finished his college career with 2,675 rushing yards, and 4,020 all-purpose yards. The latter stat lasted into the 1980s as a league record.

And yet, he was willing to risk it all over a principle -- the biggest principle of the era: Civil rights. He was 1 of 110 students who were arrested at a sit-in demonstration at the office of the University Chancellor, W. Clarke Wescoe. They were demanding an end to racial discrimination in University-approved housing, including fraternity and sorority houses.

Gale told the press, "They accept me as a football star, but not as a Negro."

*

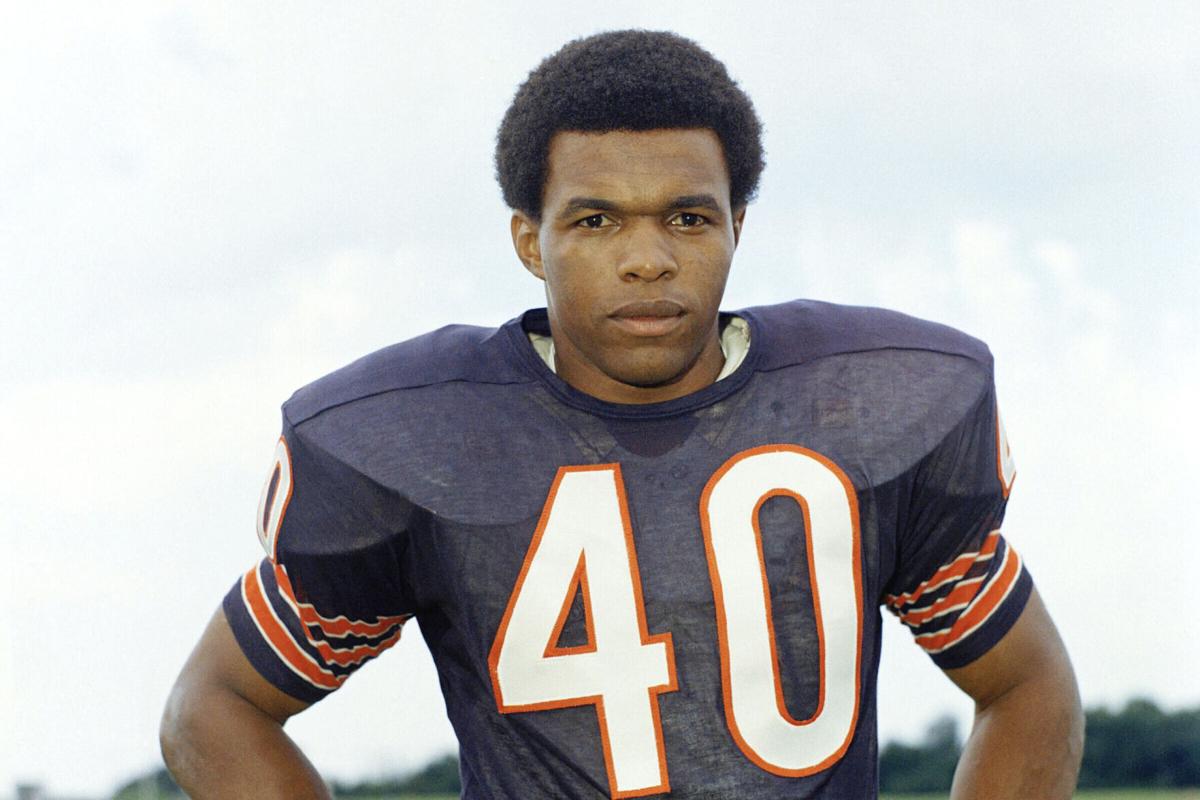

The arrest did not prevent him from having a professional football career. Both leagues drafted him: The Chicago Bears selected him with the 4th overall pick in the 1965 NFL Draft, and the Kansas City Chiefs took him 5th overall in the AFL Draft. He signed with the Bears, still coached and owned by team founder George Halas.

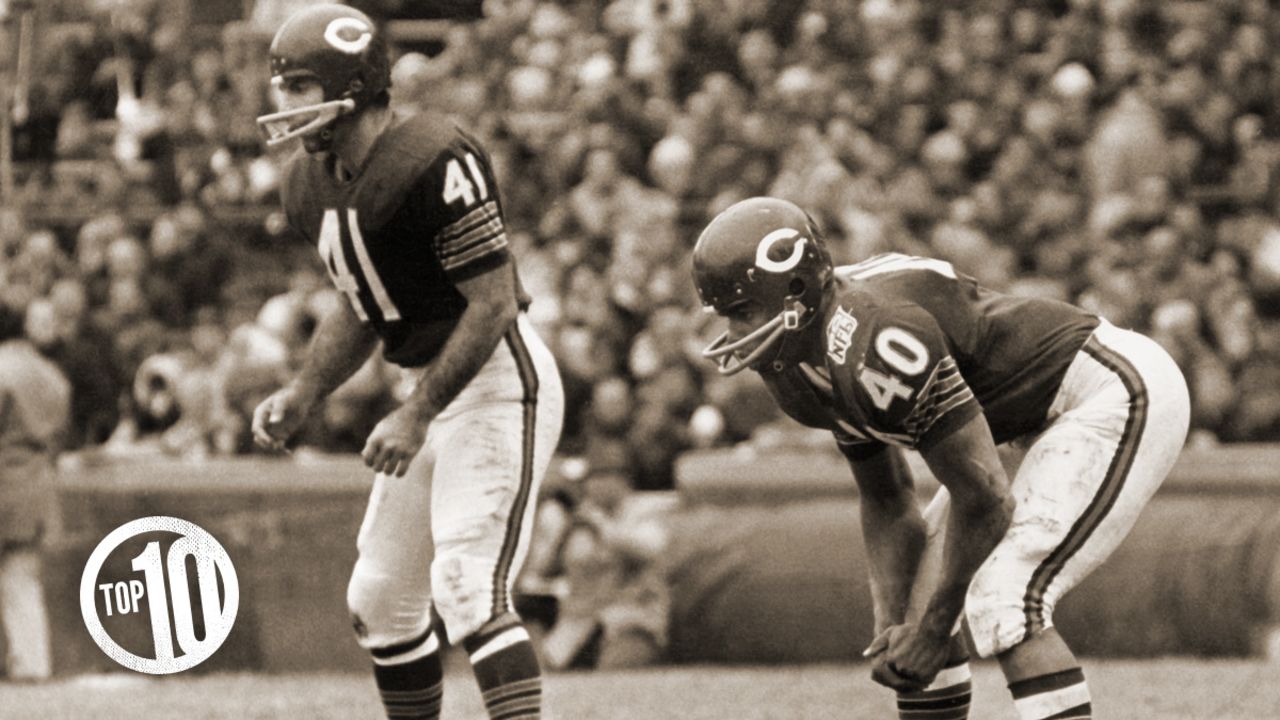

The Bears had also drafted University of Illinois linebacker Dick Butkus. Never before did an NFL team has 2 rookies like this in their lineup, and never again.

Gale Sayers scored 22 touchdowns in 1965, setting an NFL record that stood for 10 years. Think about that: 22 NFL touchdowns at age 22: 14 rushing, 6 receiving, a punt return and a kickoff return. On October 17, against the Minnesota Vikings, he had a rushing touchdown, a receiving touchdown, and a kickoff return for a touchdown in the same game. That would not happen in the NFL again until 2016, when Tyreek Hill did it for the Kansas City Chiefs.

After that game, "Papa Bear" Halas compared Sayers favorably to old-time Bears Red Grange and George McAfee. As it turned out, the Kansas Comet was just getting warmed up.

The Bears had opened the season, and thus Sayers' and Butkus' careers, on September 19 at Kezar Stadium in San Francisco, and lost 52-24. On December 12, 1965 -- not November 25, as the clip I've linked to below said -- the 49ers came to Wrigley Field, and the Bears wanted revenge. I don't think anybody expected it to take this form, though.

It rained all day, and the field on which Grange and McAfee -- and Bronko Nagurski, and Bill Osmanski, and Willie Galimore -- had run was practically a swamp. How anybody could get any speed on it was a mystery.

On that field, Gale Sayers had 113 rushing yards, 89 receiving yards, and 134 punt return yards. He scored 4 touchdowns rushing, 1 receiving, and 1 on a punt return. He had 326 total yards. He scored 6 touchdowns. That was a single-game record, previously achieved by Ernie Nevers in 1929 (who also had 4 kicking points, for a still-standing NFL record of 40 points in a game) and Dub Jones in 1951 (father of Bert Jones, and he did it against the Bears). Talk about "announcing your presence with authority."

The Bears pounded the 49ers, 61-20. One of the 49ers' receivers that day was Bernie Casey, who went on to become one of the top black actors of the 1970s. The Bears finished the season at 9-5. With 2,272 all-purpose yards, 1,371 of them rushing, Sayers was an easy choice for NFL Rookie of the Year.

He had fewer rushing yards in 1966, 1,231, but it was enough to lead the League. The Bears only went 5-7-2, and the Chicago Tribune wrote that Sayers was "the one bright spot in Chicago's pro football year."

Did someone say, "bright spot"? During that season, Sayers was interviewed for They Call It Pro Football, a short film by NFL Films, released right before the next season. (It included footage of Super Bowl I.) The film captures Sayers saying, "Give me 18 inches of daylight. That's all I need."

It wasn't arrogance: The film then showed what happened when he got at least those 18 inches. If there was a man born to run with a football while John Facenda read a script over an NFL Films soundtrack, it was Gale Sayers. Except it wasn't the martial, brassy music for which NFL Films became known that suited him: It was orchestral, string-driven music, as seen in this clip.

Or, maybe not: This clip calls him "a master of improvisation." The thought occurred to me, as I was typing this, that maybe watching Gale Sayers run with a football was like listening to John Coltrane play jazz. Sure enough, when I called up that clip, one of YouTube's other suggestions was Coltrane's soprano saxophone take on the Sound of Music song "My Favorite Things."

I've been telling people all day that, for my generation, the closest in playing style that we will get to seeing him on anything but scratchy old film is Barry Sanders. I'm just glad we have the film on Sayers. I can only surmise that it does not fully do justice to his running. I'm glad they were the same kind of person off the field, too. The world needs more people like that, and now, we have one less, and are the poorer for it.

Billy Dee Williams, who would play Sayers in Brian's Song, said, "I always sort of equated to his running style to ballet. Nijinsky. He had that kind of beauty. I loved watching him run. It was poetry." He also said it was like watching one person split into two people. Comedian Bill Cosby -- back when we liked him -- said something similar: "I did not believe what I saw. He was like an amoeba: He seemed to split into two."

The 1967 season was Halas' last as Bears had coach. He tried to diversify the Bears' offense, spreading the carries and catches around, including to Brian Piccolo, a white man born in Pittsfield, in western Massachusetts, but who grew up in Fort Lauderdale, at a time when Florida was considerably more Southern than it is now, and went to Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He had a decent college career, but was not drafted. He made the Bears as a free agent in 1965, a rookie alongside Sayers and Butkus.

In spite of Halas' attempt to stop defenses from focusing so much on one man, Gale still gained 880 yards in a 14-game season. He only returned 3 punts all season, but one was yet another mad dash across a muddy field for a touchdown against the 49ers, also returning the opening kickoff for 97 yards for a touchdown, and he ran for another, as the Bears won 28-14. They finished 7-6-1. Gale was unstoppable, the team was very stoppable.

On November 3, 1968, the Bears went into Lambeau Field to face the Green Bay Packers. Vince Lombardi had retired, so they were no longer a threat to win a 4th straight NFL Championship. Gale had a career-high 205 rushing yards, and the Bears won, 13-10.

For the 1st 50 games of his professional career, Gale Sayers may have been the single greatest runner the game of football has ever seen. Then, on November 10, 1968, disaster struck. It wasn't quite all over, but he would never be the same.

*

It was at Wrigley, and, again, the 49ers were the opponent. (By this point, Bernie Casey had been traded to the Los Angeles Rams.) In this 9th game of the season, which the Bears would win 27-19, Gale already had 856 rushing yards and was leading the League, when Kermit Alexander crashed into his right knee. Gale's anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), his medial collateral ligament (MCL), and his meniscus cartilage were torn.

"It was my fault, all my fault," Alexander said. "God, you never want to hurt a player, never. Especially a great player like Gale." Gale forgave him, understanding that things like that sometimes happen in football. He was out for the year, and was still named to a Pro Bowl in which he had no chance to play.

Piccolo became the starting fullback in his absence, and in the 1969 off-season, he put Gale through a conditioning program that got him back in shape. In addition, the Bears changed their road-hotel policy: From now on, players would room with a player of the same position. This made Gale and Brian the 1st mixed-race roommates in NFL history.

Jim Dooley, himself a former Bears running back, who had been one of Halas' last assistants and had succeeded him as head coach, installed an offense for 1969 that had Piccolo at fullback and Sayers at tailback. Somehow, having a right knee with no cartilage in it, Gale Sayers ran for 1,032 yards to lead the NFL. UPI named him the NFL's Comeback Player of the Year.

But despite having Sayers, Butkus, running back Ronnie Bull, guard Bob Wetoska, defensive end Ed O'Bradovich, linebacker Doug Buffone, and punter Bobby Joe Green, the Bears finished 1-13, their only win coming in Week 8, on November 9, 38-7 at home to the Pittsburgh Steelers, who also finished 1-13.

The Steelers got the 1st pick in the 1970 NFL Draft, and used it on quarterback Terry Bradshaw, who had a rough start to his career, but led them to 4 Super Bowl wins and the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The Bears got the 2nd pick, but had already traded it away -- to, of all teams, their rivals, the Packers. They didn't have a pick in the 2nd round, either.

And therein lay the Bears' biggest problem: Quarterbacking. Bill Wade led them to the 1963 NFL Championship. Then, during the next season's training camp, running backs Willie Galimore and Bo Farrington were killed in a car crash. That made Halas draft Sayers and sign Piccolo for 1965.

But Wade was about to turn 35 as Sayers, Piccolo and Butkus debuted. He retired after the 1966 season, having lost the starting job to Rudy Bukich, who was not up to the task. Nor was Jack Concannon, who became the starter in 1969. Nor was Bobby Douglass, although he did go on to set an NFL record for rushing yards by a quarterback in 1972.

Without a good quarterback, the Bears never got close to a Playoff berth. Although 1969 was their only truly dreadful season, record-wise, while Sayers was on their roster, they were 39-54-3 during his career, and 46-74-4 while Butkus was on their roster.

To put it another way: Since Sid Luckman -- along with Sammy Baugh of the Washington Redskins -- invented the modern position of quarterback, the Bears have been to the NFL Championship Game, known as the Super Bowl from 1967 onward, 9 times: 5 under Luckman (1940, '41, '42, '43 and '46, winning each of those except '42), and 1 each under Ed Brown (1956, losing), Wade (1963, winning), Jim McMahon (1985, winning Super Bowl XX) and Rex Grossman (2006, losing Super Bowl XLI). That's it: Since the NFL's reintegration season of 1946, the Bears have been to just 4 NFL title games, winning 2, in 74 seasons.

The Bears had one other thing in common with the Steelers in 1969: It was time for the old man, the founder, to pass the team on to the next generation. Dan Rooney and his brother Art Rooney Jr. told their father, Art Rooney Sr., that it was time, and he agreed, and the Steelers built one of the greatest teams ever.

In contrast, George Halas acted more like Connie Mack with the Philadelphia Athletics: No matter who was officially the head coach or the general manager, he was going to be in charge no matter what, but the idea was that, eventually, he would pass control to George Halas Jr., a.k.a. Mugs, whom he named team president in 1963.

But he never truly ceded control to Mugs. And at the end of the 1979 season, Mugs died of a heart attack, only 54 years old. Papa Bear lived another 4 years, age 88, and left control of the team to his daughter, Virginia Halas McCaskey. She held the stock, and left operational control to her husband, Big Ed McCaskey, who left the running of the team to their son, Mike McCaskey.

They built the team that won Super Bowl XX, but, like the New York Mets, for all their talent, they only won the title in calendar year 1986 (in the Bears' case, the 1985 season), and their other close calls were unsuccessful. Eventually, Ed took the keys back from Mike, and handed them to their other son, George Halas McCaskey. Today, he and team president Ted Phillips run the team for his mother Virginia, at 97 the oldest NFL team owner ever.

Still, given their place in NFL history, and the resources available, in one of the biggest markets in America, the Bears are one of the great underachievers in American sports. And it all goes back to George Halas being unwilling to adapt to the times.

Part of it was his stinginess: Mike Ditka, one of his greatest players, and the last head coach he would ever hire, once said, "George Halas throws nickels around like manhole covers." And so, in competitive terms, a season like 1969 was practically inevitable.

What no one could have foreseen was what happened to Brian Piccolo. The game after the team's only win of the season, he took himself out of the game, something he had never done before. He told team management that he was having trouble breathing. When the team got back to Chicago, he was examined, and found to have cancer.

What kind is not clear. Obviously, it had gotten into his lungs, and that became the official story, including in Brian's Song. But his lungs may not have been where it started: One source I found said it was embryonal cell carcinoma, which starts in women in the ovaries and in men in the corresponding organs, the testicles -- a part of the body that was not discussed in polite company in those days, and certainly couldn't be mentioned on television in 1971. (All In the Family mentioned menopause in 1972, and used the word "breast" in 1973, but it would be a while longer before male sex organs could be mentioned on primetime network TV.)

Brian's tumor was removed, but it wasn't enough. In April 1970, his left lung was removed. It turned out that the cancer had spread to his liver, and he was doomed. A few days later, at a banquet in New York, a few blocks from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the world's foremost hospital for treating cancer, Sayers was given the George S. Halas Award for the NFL's most courageous player.

He told the banquet who he thought the award really belonged to: "I might have received this award tonight, but, tomorrow, I will take it to Brian Piccolo at Sloan Kettering. I love Brian Piccolo, and I'd like all of you to love him, too. Tonight, when you hit your knees to pray, please ask God to love him, too."

None of it was enough: Brian died on June 16, 1970, only 26 years old. Halas, who had gone against his frugal tendencies and paid every cent for Brian's medical care, also paid for his funeral. Sayers and Butkus were among his pallbearers.

That year, Gale published an autobiography, titled I Am Third, meaning God was first and his family was second. But the way he wrote about Brian, Gale made himself sound like he was fourth, and his friends, like Brian, were third.

In 1972, he wrote a 2nd book, with Miami Dolphins quarterback Bob Griese, an instruction manual titled Offensive Football. In 2007, he published another autobiography, Sayers: My Life and Times.

On November 30, 1971, ABC aired the TV-movie Brian's Song, based on Gale's book. Gale was played by Billy Dee Williams. It made him a star, launching him to a career that included his role as Lando Calrissian in the Star Wars films, a status as a romantic leading man, and, playing off that image, his commercials for Colt 45 malt liquor ("It works every time").

(I wonder if he had to call himself "Billy Dee Williams" because of another Chicago athlete of that era. Future Baseball Hall-of-Famer Billy Williams, then with the Cubs, or perhaps another actor, might have already registered the name "Billy Williams" with the Screen Actors Guild. See also: Vanessa L. Williams, no relation to either of the preceding; and Michael B. Jordan.)

Brian was played by James Caan, who was a little better-known at that point, but this role got him cast as Sonny Corleone in The Godfather. He would play a very different kind of athlete in the 1975 dystopian-future film Rollerball.

Halas was played by Jack Warden, Brian's wife Joy by Shelley Fabares (who would again play a football wife on the sitcom Coach), Gale's wife Linda McNeil Sayers by Judy Pace, Bears running back J.C. Caroline by Bernie Casey, and several still-active Bears as themselves, including Butkus, O'Bradovich and Concannon.

Brian's Song was the most-watched made-for-TV movie ever to that point, and has been called the 1st film over which it was okay for men to cry. It has become even more iconic than Gale and Brian themselves, to the point where later TV shows had women pregnant with twins that their husbands will not get to name the sons Gale and Brian.

ABC produced a remake in 2001, at a time when there was less of a stigma about cancer, and Sean Maher could portray a dying Brian with a terribly emaciated look. Mekhi Phifer played Gale. Gale's autobiography was re-released, with an update, and was officially retitled I Am Third: The Inspiration for Brian's Song.

But by the time the original version aired, it was all over for Gale. He injured his left knee during training camp in 1970, and played just 2 games that season, before realizing that his "good knee" wasn't going to get any better, and had season-ending surgery. During his time off, he took classes, and became the 1st black stockbroker at Paine Webber & Co. (That firm, known for its "Thank you, Paine Webber" TV commercials, was absorbed by Swiss company UBS in 2000.)

He played just 2 games in 1970, and 2 more the next season, the Bears' 1st at the original Soldier Field, having to move there since Wrigley Field had no lights until 1988. His last regular-season game was on October 17, 1971. Once again, the 49ers were the opponent for a key game in his career. It was at Candlestick Park -- also the site of the Beatles' last official concert, 5 years earlier. He had only 5 carriers, for 8 yards, before injuring his ankle. The Bears lost, 13-0. He tried one more time, but was ineffective in the 1972 preseason, and retired.

It's just as well: 1971 was the 1st season that the Bears played their home games on artificial turf, and would continue to do so in 1987, switching back to natural grass the following year. Of the 26 teams in the NFL after the 1970 merger with the AFL, 9 of them had artificial turf. By 1976, it would be 15 out of 28.

Gale Sayers rushed for 4,956 yards. He caught 112 passes for 1,307 yards. Counting returns, he had 9,044 total yards, for 56 touchdowns. That would be a pretty good career for most players.

Instead, he had only half a career, much like Sandy Koufax in baseball and Bobby Orr in hockey. Koufax retired just before turning 31, due to an elbow issue, although only in 1 season did he miss significant time. Orr retired just before turning 31, like Sayers due to injuries to both knees, having played only enough games to add up to 9 full seasons.

Gale Sayers played 68 games, slightly more than 4 full 16-game seasons by today's standards, retiring at age 28. He played only 4 games past age 26. To put it another way, he never really got to have a healthy prime. Imagine if, instead of drugs, Dwight Gooden had only his injuries. Or if, after his 50.4 points-per-game season, including 100 in 1 game, in 1961-62, Wilt Chamberlain had gotten hurt, and struggled the rest of the way.

Billy Sims won the Heisman Trophy at Oklahoma in 1978, and nearly won it again in 1979. He rushed for 5,106 yards for the Detroit Lions, more than Sayers. He caught 186 passes for 2,072 yards, almost twice as much as Sayers in each category. But he landed on his knee on the Metrodome turf halfway through his 5th season, and never played again. He is in the College Football Hall of Fame, but not the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

William Andrews played 5 seasons for the Atlanta Falcons, making 3 Pro Bowls. In training camp of his 6th season, he wrecked his knee, and only played another 15 games. He finished with 5,986 yards rushing, and 277 catches for 2,647 yards. In each of those stats, he's ahead of Sims, never mind Sayers. But he is not in the College or the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Gale Sayers is in both Halls. It helped that he was in a major market, Chicago, unlike Sims in Detroit and Andrews in Atlanta. It also helped that he was an icon for Baby Boomers, the same way Johnny Unitas, Joe Namath, and Lombardi's Packers were. It also helped that, despite his sit-in on the KU campus, he wasn't grumpy or an agitator, like Jim Brown, who also retired early, albeit not due to injury. Gale had the moves, and the personality, and the story. In the end, those things mattered more than the stats, as impressive as they were for the 1st 4 years.

*

And so, in 1977, in his 1st year of eligibility, Gale was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, just 34 years old. Like Koufax in baseball (36) and Orr in hockey (31, the waiting period for eligibility waived in his case), he was the youngest living person ever elected, and none of those distinctions is ever likely to be beaten.

Like many other collegiate sports legends, Gale went back to his alma mater. After finishing his degree at KU in 1972, he was named an official in its athletic department. Southern Illinois University noticed his work back in Lawrence, Kansas, and in 1976, they named him their athletic director. He held that post until 1981. In the 1985-86 schoolyear, he served as athletic director at Tennessee State University, a historically black school in Nashville, best known for its "Tigerbelles" women's track team, which had produced, among others, 1960 Olympic heroine Wilma Rudolph.

In 1984, he founded Crest Computer Supply Company, later renamed Sayers 40, Inc., for his uniform number, and later renamed Sayers Technology. His timing was right on the money, as the growth of personal computers made him more money than he could have made playing football in the modern era. Sayers 40 branched out into technology consulting.

With his 2nd wife, Ardythe Bullard Sayers, he also started a charitable foundation for underprivileged kids and an adoption agency. In 2009, he returned to Kansas as Director of Fundraising for Special Projects.

Gale was father to a daughter, Gale Lynne; 2 sons, Timothy and Scott; and 2 stepsons, Gaylon and Gary. He lived to see 2 grandchildren.

On October 31, 1994, the Bears played the Packers in the NFL's oldest, and perhaps nastiest, rivalry on Monday Night Football. An appropriate matchup for Halloween Night. Bear management decided to give the nationwide TV audience a look at a long-overdue ceremony: The retirements of the uniform numbers of Gale Sayers, 40; and Dick Butkus, 51. Kansas had already retired the 48 that Sayers wore there, and Illinois had already retired the 50 that Butkus wore.

But the weather was scarier than the holiday. It rained all night. And a cold wind came blasting in off Lake Michigan. This was not "Bear Weather," with frigid temperatures and perhaps snow: This was close to a hurricane. Walter Payton, now retired from a career as the next great Bears running back, stood on the sideline, all wrapped up in plastic, including his feet. During the ceremony, Helen Butkus was nearly injured when the wind inverted her umbrella.

You can actually see the rain falling diagonally in this photo.

Mike McCaskey, already unpopular among Bears fans, got booed. Butkus, Sayers, and, through Sayers' mention of him, the memory of Brian Piccolo all got cheered. When the ceremony was over, with the Bears still in the game at 14-0, a big chunk of the crowd, officially listed at just 47,381 due to the bad weather, left. They didn't miss much: The Packers went on to win 33-6.

In 1999, The Sporting News named its 100 Greatest Football Players. Sayers was ranked 22nd, and Butkus 9th, 2nd only to Lawrence Taylor among defensive players. In 2010, the NFL Network named its 100 Greatest Players. Sayers was again ranked 22nd, Butkus 10th. This, despite both of them having devastating knee injuries, and despite an additional 11 years of players who could have surpassed them. Both men were named to the NFL's 75th and 100th Anniversary All-Time Teams, and to both the College and the Pro Football Halls of Fame.

In 2013, having begun to suffer from headaches and short-term memory loss, Sayers went to the famed Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, was diagnosed with dementia. His wife announced it in 2017, saying, "It wasn't so much getting hit in the head. It's just the shaking of the brain when they took him down with the force they play the game in."

He certainly wasn't the 1st great player to be given this kind of diagnosis, and he won't be the last. Physically, he was still fine. That wasn't the case with Butkus, who was the other way around: Although his mind remains clear, he sustained damage to his neck, back, hips, knee, and digestive system. Like Donald Trump, he now needs both hands to lift a cup or a bottle. He turns 78 in December, and still believes that football had a largely positive impact on his life, but lives in constant pain.

Gale Sayers' pain is over. He died yesterday, September 22, 2020, at his home in Wakarusa, Indiana, about 110 miles east of Chicago and 20 miles south of the Notre Dame campus in South Bend, at the age of 77.

The Bears' Twitter feed: "It is with great sadness the Chicago Bears mourn the loss of Bears Hall of Fame running back Gale Sayers. Sayers amplified what it meant to be a Chicago Bear both on and off the field. He was regarded as an extraordinary teammate, leader, husband and father."

The Chicago Cubs' Twitter feed: "The Cubs are saddened by the loss of Bears Hall of Fame RB Gale Sayers. We join the Chicago sports community and football world in mourning the passing of a legend who made a home at Wrigley Field."

A first ball ceremony at Wrigley Field.

Presumably, at that age, he needed more

than 18 square inches of strike zone.

Dick Butkus: "We will miss a great friend who helped me become the player I became because after practicing and scrimmaging against Gale, I knew I could play against anybody. We lost one of the best Bears ever, and, more importantly, we lost a great person."

Sayers and Butkus at Wrigley Field's 100th Anniversary celebration, 2014

Mike Ditka, Bears Hall of Fame tight end and Super Bowl-winning head coach: "People will say there were better players, but I don't know who they are. I don’t know anybody that ran the football any better than Gale Sayers. I played in that game he scored 6 touchdowns. Everybody was slipping and sliding and he kept scoring. He was special. He was magic. He made things happen."

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell: "The NFL family lost a true friend today with the passing of Gale Sayers. Gale was one of the finest men in NFL history and one of the game's most exciting players."

Jim McMahon, quarterback of the Bears' Super Bowl XX winners: "Tough to hear the news about Gale Sayers. Not only was he 1 of the most electrifying players of any generation, he was an ever better person."

Ernie Accorsi, a sportswriter for most of Gale's career, before a 46-year front office career that included a Super Bowl win as Baltimore Colts public relations director and an NFC Championship as New York Giants general manager: "Gale Sayers was the greatest halfback I ever saw. I never saw anyone who could be at full speed, stop on a dime and, in one step acceleration, be at top speed again. I saw runs he made that if it was one-handed touch football, instead of tackle, they couldn’t have caught him."

Cubs Hall-of-Famer Fergie Jenkins: "Very sad to hear of the passing of @ChicagoBears great Gale Sayers. A true legend."

Chicago Bulls Hall-of-Famer Scottie Pippen: "Gale Sayers was someone who I admired long before I arrived in Chicago. I loved his approach to the game and of course, how he played it. He inspired me to be great in a city that loves sports like no other."

Asthon Kutcher, actor and entrepreneur, who grew up a Bears fan in Cedar Rapids, Iowa: "I asked Gale Sayers for the best advise he ever received. From his HS football coach: 'When it's you vs 1 person you should win 100% of the time, when it's you vs 2 people you win 75% of the time. Set your expectations higher than others imagine, then exceed them.' RIP #BearDown"

Sayers and Kutcher at the new Soldier Field

Billy Dee Williams: "My heart is broken over the loss of my dear friend, Gale Sayers. Portraying Gale in Brian's Song was a true honor and one of the nightlights of my career. He was an extraordinary human being with the the kindest heart."

Michael Wilbon, Chicago native and co-host of ESPN's Pardon the Interruption: "I grew up watching Gale Sayers, and used to feel sorry for myself as a little kid because Gale got hurt so soon. He occupies a place alongside Ernie Banks and Mike Ditka and a handful of great athletes in Chicago."

There are no knee injuries in Heaven. No muddy, chopped-up fields, either. And he has all the daylight any runner could ever need. Now, he can run to his heart's content.

With regards to Brian Piccolo and George Halas, Halas also made sure Brian's kids had money to go to college and even made sure his widow kept their house, in addition to taking care of all of their expenses. Say what you will about Halas, but this was one of his best acts, IMO...

ReplyDeleteWith regards to being cheap, part of it was that he lived through the Great Depression, so he may have been more cheap for that reason, IMO...

What you said about Halas and the Piccolos is true. But Halas was already 34 years old when the Crash of 1929 happened. The Great Depression was not a formative experience for him. And he was born in 1895, during the last depression, so he would have had no memory of it. He might have been poor as a boy, which might explain his cheapness, but it wasn't during a depression.

ReplyDelete