The legend lives on from Ipanema on down

of the sport called O Jogo Bonito.

It's said that the game has brought plenty of fame

but the bounces of July can beat you.

In 1950, Brazil, the country that would eventually give the sport of soccer the name "O Jogo Bonito" -- The Beautiful Game -- hosted the World Cup for the 1st time.

The World Cup had first been held in 1930, in Uruguay, and the host nation won it. That wasn't surprising, since they had won the Olympic Gold Medal in 1924 and 1928. Brazil split its 2 games, and was not 1 of the 4 teams that progressed to the knockout stage.

The 1934 edition, in Italy, was a simple knockout stage of 16 teams, and Brazil lost to Spain in the 1st round. Again, the hosts won. The same format was used in France in 1938, and Brazil got to the Semifinal, before losing to Italy, who won again.

Brazil had been promised the 1942 World Cup, because it was neutral in World War II, but the war made holding the tournament impossible. Most of the countries that would have participated in 1946 were still rebuilding, so that tournament was canceled as well. So Brazil was granted hosting rights for 1950.

They built new stadiums in their major cities, including a new national stadium, the Estadio

Maracanã, in their capital city, Rio de Janeiro. (The city of Brasilia was already being constructed as a new, more centrally-located capital, and it opened in 1960.) With standing room, it could hold 200,000 people.

Brazil, with its footballing roots in several nations, including England, Spain, Italy, and its former colonial master Portugal, was considered one of the favorites in the tournament. They had a relatively easy Group Stage, beating Mexico 4-0, being held to a 2-2 draw by Switzerland, and beating Yugoslavia 2-0. It was no easy group: In modern times, this might have been called "The Group of Death," which every international tournament seems to have.

England and America were put in a separate group, and on June 29, 1950, in Belo Horizonte, the U.S. shocked their own former colonial masters 1-0. It is still considered the biggest upset in World Cup history. But it would not turn out to be the most devastating defeat of this tournament.

The Group winners were put in a final Group, with the winner of the Group to be declared the winner. This is the only time that this format has been used in the World Cup. On July 9, Brazil thrashed Sweden 7-1 at the Maracanã, and Uruguay and Spain played to a 2-2 draw in São Paulo. On July 13, Brazil beat Spain 6-1 at the Maracanã, and Uruguay beat Sweden 3-2 in São Paulo.

The World Cup had first been held in 1930, in Uruguay, and the host nation won it. That wasn't surprising, since they had won the Olympic Gold Medal in 1924 and 1928. Brazil split its 2 games, and was not 1 of the 4 teams that progressed to the knockout stage.

The 1934 edition, in Italy, was a simple knockout stage of 16 teams, and Brazil lost to Spain in the 1st round. Again, the hosts won. The same format was used in France in 1938, and Brazil got to the Semifinal, before losing to Italy, who won again.

Brazil had been promised the 1942 World Cup, because it was neutral in World War II, but the war made holding the tournament impossible. Most of the countries that would have participated in 1946 were still rebuilding, so that tournament was canceled as well. So Brazil was granted hosting rights for 1950.

They built new stadiums in their major cities, including a new national stadium, the Estadio

Maracanã, in their capital city, Rio de Janeiro. (The city of Brasilia was already being constructed as a new, more centrally-located capital, and it opened in 1960.) With standing room, it could hold 200,000 people.

Brazil, with its footballing roots in several nations, including England, Spain, Italy, and its former colonial master Portugal, was considered one of the favorites in the tournament. They had a relatively easy Group Stage, beating Mexico 4-0, being held to a 2-2 draw by Switzerland, and beating Yugoslavia 2-0. It was no easy group: In modern times, this might have been called "The Group of Death," which every international tournament seems to have.

England and America were put in a separate group, and on June 29, 1950, in Belo Horizonte, the U.S. shocked their own former colonial masters 1-0. It is still considered the biggest upset in World Cup history. But it would not turn out to be the most devastating defeat of this tournament.

The Group winners were put in a final Group, with the winner of the Group to be declared the winner. This is the only time that this format has been used in the World Cup. On July 9, Brazil thrashed Sweden 7-1 at the Maracanã, and Uruguay and Spain played to a 2-2 draw in São Paulo. On July 13, Brazil beat Spain 6-1 at the Maracanã, and Uruguay beat Sweden 3-2 in São Paulo.

The final day was July 16, and Sweden's game with Spain in São Paulo was meaningless. Sweden won it 3-1. It was all down to Brazil vs. Uruguay, neighboring nations, at the Maracanã. Brazil had cruised, except for their draw with Switzerland. Uruguay had considerably more trouble in advancing.

Centre forward Ademir had already scored 8 goals, a record for a single World Cup that ended up standing until 2002. Goalkeeper Moacir Barbosa and the Brazil defense had allowed just 4 goals in 5 games.

Given the goal difference, all Brazil had to do was gain a draw, and they would be World Champions on home soil. Uruguay, on the other hand, had to win.

Furthermore, the previous year, also in Brazil, Brazil had won the national-team continental championship, the Copa América, rather easily, including a 5-1 win over Uruguay. And so it seemed a foregone conclusion that the home team would win.

O Mundo (The World), a national newspaper, printed an early edition, with the Brazil team's picture on the front page, with the headline, "These are the world champions." Not for the first time, and certainly not for the last, an incendiary headline was posted in the other team's locker room. Uruguay's Captain, Obdulio Varela, bought several copies of the paper, took them to his hotel room, brought his teammates in, laid the copies on the bathroom floor, and had them piss all over the copies.

In the locker room before the game, Varela told his teammates, "If we play defensively against Brazil, our fate will be no different from Spain or Sweden." He then delivered a pep talk, inspiring them to attack the whole way, concluding with, "Boys, outsiders don't play. Let's start the show."

*

The fans filed into the Maracanã. It remains the largest paying crowd in soccer history, 199,854. (With conversion to all-seater and various renovations since, the Maracanã now has a capacity of 78,838, still big, but not huge.) These were the starting lineups. For Brazil, wearing all-white uniforms:

Centre forward Ademir had already scored 8 goals, a record for a single World Cup that ended up standing until 2002. Goalkeeper Moacir Barbosa and the Brazil defense had allowed just 4 goals in 5 games.

Ademir

Given the goal difference, all Brazil had to do was gain a draw, and they would be World Champions on home soil. Uruguay, on the other hand, had to win.

Furthermore, the previous year, also in Brazil, Brazil had won the national-team continental championship, the Copa América, rather easily, including a 5-1 win over Uruguay. And so it seemed a foregone conclusion that the home team would win.

O Mundo (The World), a national newspaper, printed an early edition, with the Brazil team's picture on the front page, with the headline, "These are the world champions." Not for the first time, and certainly not for the last, an incendiary headline was posted in the other team's locker room. Uruguay's Captain, Obdulio Varela, bought several copies of the paper, took them to his hotel room, brought his teammates in, laid the copies on the bathroom floor, and had them piss all over the copies.

In the locker room before the game, Varela told his teammates, "If we play defensively against Brazil, our fate will be no different from Spain or Sweden." He then delivered a pep talk, inspiring them to attack the whole way, concluding with, "Boys, outsiders don't play. Let's start the show."

*

The fans filed into the Maracanã. It remains the largest paying crowd in soccer history, 199,854. (With conversion to all-seater and various renovations since, the Maracanã now has a capacity of 78,838, still big, but not huge.) These were the starting lineups. For Brazil, wearing all-white uniforms:

1 Moacir Barbosa, goalkeeper, of Rio club Vasco da Gama.

2 Augusto da Costa, right fullback and Captain, also of Vasco.

3 Juvenal Amarijo, left fullback, of Rio club Flamengo.

4 José Carlos Bauer, right halfback, of São Paulo FC.

5 Danilo Alvim, centre halfback, of Vasco.

6 João Ferreira, a.k.a. Bigode, left halfback, of Flamengo.

7 Albino Friaça, outside right forward, of São Paulo FC.

8 Thomaz Soares da Silva, a.k.a. Zizinho, inside right forward, of Flamengo.

9 Ademir de Menezes, centre forward, of Vasco.

10 Jair da Rosa Pinto, inside left forward, of São Paulo club Palmeiras.

11 Francisco Aramburu, a.k.a. Chico, outside left forward, of Vasco.

For Uruguay, wearing sky blue shirts and navy blue shorts, with each playing for a club team in the national capital of Montevideo:

1 Roque Máspoli, goalkeeper, of Club Atlético Peñarol, the country's most successful team.

2 Matías González, right back, of Cerro.

3 Eusebio Tejera, left back, of Nacional.

4 Schúbert Gambetta, right half, of Nacional.

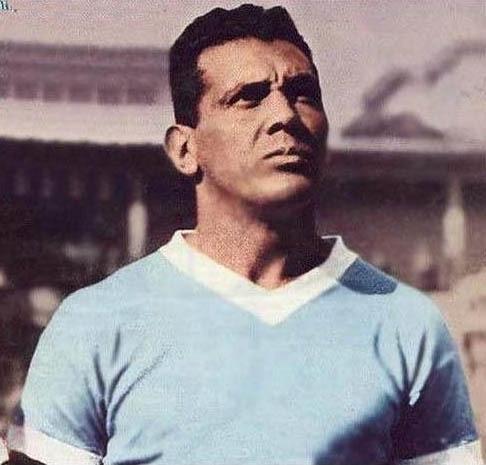

5 Obdulio Varela, centre half and Captain, of Peñarol.

6 Víctor Rodríguez Andrade, left half, of Central Español, and would later star for Peñarol.

7 Alcides Ghiggia, outside right, of Peñarol, and would later star in Italy for A.S. Roma.

8 Julio Pérez, inside right, of River Plate (the one in Montevideo, not the better-known one in Buenos Aires, Argentina).

9 Óscar Omar Miguez, centre forward, of Peñarol.

10 Juan Alberto Chiaffino, a.k.a. Pepe, inside left, of Peñarol.

11 Rubén Morán, outside left, of Cerro.

At 3:00 PM local time -- 1:00 U.S. Eastern, 6:00 in Britain, and 7:00 in Western Europe -- the referee, George Reader of England, blew his whistle, and the game was underway. Brazil attacked immediately, but Uruguay held, and the 1st half ended scoreless.

Shortly after play resumed, Friaça put Brazil on the board. The gigantic crowd was ecstatic. Again: Brazil didn't have to win, because, with goal difference, a draw would also have given them the Cup. So being 1-0 up in the 2nd half made it look like all the hype and all the confidence had been worth it.

But Varela was smart: He went to the referee, and disputed the validity of the goal. He didn't speak English, and Reader didn't speak Spanish. An interpreter was found, and Reader learned Varela's objection: He believed (or said he did) that Friaça was offside. Reader called the linesman over, and the linesman denied it. Reader made his decision final: The goal stood.

Obdulio Varela

Varela didn't get everything he wanted, but he got a big thing that he wanted: He stopped Brazil's momentum. They were standing around, waiting for play to be allowed to resume. Their fans had calmed down a bit. The home-field advantage had been dented. Reader handed the ball to Varela, who took it to the center of the field, and shouted to his teammates, "Now, it's time to win!"

And they did as he wanted: They attacked. Brazil didn't have a defense as good as their offense, and, in the 66th minute, Pepe equalized for Uruguay. That didn't matter much: If that 1-1 score had held, Brazil would still be World Champions.

In the 79th minute, Ghiggia ran down the right sideline, and fired a low shot that went under Barbosa. It was Uruguay 2, Brazil 1. Every Brazilian -- on the pitch, in the stadium, and listening on the radio -- was in shock. Brazil attacked the rest of the way, but couldn't find the all-important equalizer. The home crowd was quiet.

Alcides Ghiggia

Shortly after 5:00, Reader blew his whistle to end the match. Uruguay had now won 2 of the 1st 4 World Cups. Brazil had lost the world championship of their national sport, in their national stadium.

In that stadium, 3 fans died from heart attacks. Another, who had brought a gun in, killed himself.

There was no public ceremony. Rimet wisely chose to present the trophy that would later bear his name to Uruguay in their locker room.

Outside that stadium, a group of fans knocked over a bust of Mayor Mendes. Brazil manager Flavio Costa had to leave the stadium in disguise -- as a nanny. Yes, like some deposed dictators have done, he left in drag, so as not to be recognized.

*

The loss was a blow to the national psyche, so often wrapped up in this sport of soccer. It is known as Maracanazo in Spanish, Maracanaço in Portuguese: "The Agony of Maracanã."

You think losing the Gold Medal in basketball to the Soviets in the 1972 Olympics in Munich was bad for the U.S.? You think the shock of losing the opening game of the "Summit Series" to the Soviets a week before was a blow to Canada, though they dramatically won the series anyway? You think losing the Gold Medal in hockey to the U.S. in the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid was a devastating defeat for the Soviets? You think any World Cup loss by England, or Italy, or any other country compares?

The 1950 World Cup was supposed to be a statement for Brazil, showing the world that is was a modern country, worthy of respect and admiration around the postwar world. This was the country's coming-out party, and it was ruined. Minister of Sport Aldo Rebelo said, "Losing to Uruguay in 1950 not only impacted on Brazilian football, it impacted on the country's self-esteem." Instead of hating Uruguay for the ruination, Brazilians blamed themselves.

They needed that boost for their self-esteem. Brazil, like many other countries, is a young nation but an old civilization. And, as with those other countries, its old civilization had been built up by a European power, but also severely damaged by one. Very little of what the colonizing nation liked was accepted. But, as with the Caribbean and India with cricket, and South Africa with rugby, Brazil was one of those countries that took to soccer as the colonizers had taught it.

There was a racial aspect as well. From 1502 to 1860, 38 percent of slaves brought to the New World ended up in Brazil, and it became the last country in the Western Hemisphere to outlaw slavery, doing so in 1888. The descendants of slaves became scapegoats for what went wrong in Brazilian society. But it was black footballers, more than the white ones, that had brought glory to the national team, the Seleção, including winning the Copa América in 1919, 1922 and 1949, and helping to unify the vast, diverse nation.

Much of the blame for the defeat fell upon goalkeeper Moacir Barbosa, who was black. He continued to be a scapegoat even after Brazil's greatest victories. In 1994, he wanted to meet with the keeper on that year's Brazil World Cup team, Cláudio Taffarel. But Mário Zagallo, who played on the 1958 and 1962 wins, and managed the 1970 win, was now the overall boss of Brazilian football, and forbid it. And Brazil won, with Taffarel keeping 5 clean sheets in 7 games, including the Final.

Moacir Barbosa died in 2000. He had lived to see Brazil win the World Cup 4 times, and become the most admired nation in the world at the sport. Shortly before his death, he said, "Under Brazilian law, the maximum sentence is 30 years. But my imprisonment has been for 50 years."

Even the two most famous photos of him,

taken inside a goal, makes it look like he's in a cage.

Barbosa wasn't the only scapegoat. Brazil wore white shirts that day, and have never worn them again: Always yellow when they have the choice, otherwise green.

Also, one of Brazil's proudest clubs took some of the blame. There were 5 players in the starting lineup for the 1950 "Final" who played at Club de Regatas Vasco da Gama in Rio. The team, which started as a rowing club (Regatas = Rowing), was named for the Portuguese explorer (1460-1524) remembered for his voyages not to South America, as a modern observer might think, but to Africa and India.

Since 1950, Vasco have won the Brazilian national league 4 times, most recently in 2000; the Rio State Championship 15 times, most recently in 2016, for a total of 24 titles; and the South American continental club championship, the Copa Libertadores, in 1998. Despite this, there was a stigma on the club, taking some of the blame for the 1950 loss.

This is the total number of Vasco players on Brazil's World Cup entire squads since: 1954, 3; 1958, winning it, 3; 1962, winning it, none; 1966, 1; 1970, winning it, none; 1974, none; 1978, 3; 1982, considered one of the best teams ever despite not reaching the Final, 2; 1986, none; 1990, 5, but by now it had been 40 years; 1994, winning it, 1; 1998, reaching the Final, 1, a backup goalkeeper who saw no time in the tournament; and in 2002, which they won, plus 2006, 2010, 2014 and 2018 combined, exactly none.

There is a more tragic element to the loss, and I mean true tragedy, not the loss itself. Manuel Marinho Alves, known as Maneca, was another Vasco player on the 1950 Brazil team, playing in 4 games and scoring a goal, but didn't play in the Final.

In his career, he would help Vasco win 4 State Championships, and the South American Club Championship (the predecessor tournament to the Copa Libertadores) in 1948. But he never got over the Maracanazo, and on June 28, 1961, at his girlfriend's house, he committed suicide by mercury poisoning. He was only 35 years old.

Only 1 player on the 1950 Brazil team was still there to win the 1958 World Cup: Nílton Santos, who barely played in 1950, and was not one of those held responsible. He was also the last survivor of the 1950 team, living until 2013. Juvenal, the left back, was the last survivor of those who actually played in the game, living until 2009.

Brazil have gone on to win the World Cup a record 5 times: Beating Sweden in the Final in Sweden in 1958, beating Czechoslovakia in the Final in Chile in 1962, beating Italy in the Final in Mexico City in 1970, beating Italy in the Final again in the Rose Bowl in 1994, and beating Germany in Japan in 2002. They have also lost the Final to France in Paris in 1998.

You will notice that none of those 5 wins have been in Brazil. The World Cup has returned to that country only once, in 2014, and Brazil got to the Semifinal, but had an even more stunning loss at the Maracanã. It wasn't that they lost to Germany, who then beat Argentina in the Final. It wasn't even that they were looking forward to beating Argentina in the Final in the Maracanã themselves. It was the score: Germany beat Brazil, in the Maracanã, by a score of 7-1.

There is another legend of Maracanazo: João Ramos do Nascimento, a striker for Bauru known as Dondinho, was listening to the game on the radio, and cried at the result. His 9-year-old son, Edson Arantes do Nascimento, told his father that, one day, he would win the World Cup, for him, and for Brazil.

In 1958, Edson, by then called Pelé and playing for Santos in São Paulo State, kept that promise. He repeated it in 1962 and 1970. Dondinho lived until 1996, so he saw his son become an icon in American soccer as well, and he also saw Brazil's 1994 World Cup win.

The last surviving player from the game was Alcides Ghiggia, who died on July 16, 2015, 65 years to the day after he scored the winning goal for Uruguay.

*

Much as the 1980 and 2008 World Series wins have not fully erased the humiliation of the blown 1964 National League Pennant for Philadelphia Phillies fans, Brazilians still have not gotten over Maracanazo after 70 years, despite winning 5 World Cups and the admiration of the rest of the world.

Should they let themselves, and the 1950 players, off the hook?

Top 5 Reasons You Can't Blame Brazil for losing the 1950 World Cup

5. The Brazilian Media. Modern observers of international tournaments see how the media in England builds their national team up as sure winners. The England theme in 2018 was "It's coming home." They were right, but not in the way they think: "It," the World Cup trophy, is known as the Jules Rimet Trophy, for the longtime President of FIFA, who founded the tournament. And the tournament and the trophy were won by his homeland, France.

Brazil is no different. Their success in the "Baby Boom" years, winning in 1958, 1962 and 1970, made them many a neutral fan's "second team" in World Cup play thereafter. (That, and the many TV shots of gorgeous Brazilian women in tight yellow team shirts.) When Brazil won in 1994 and 2002, lots of people with no connection to the country were happy for them (if not as happy as they would have been if their own team had won it).

The shocking defeat the next time the World Cup was in Brazil, the 7-1 demolition by Germany in the Semifinal, hurt a great deal, because this was supposed to be it. But it wasn't. As I said, Brazil have won the World Cup a record 5 times, and it's never been in Brazil.

For whatever reason, Brazil seem to do better away from home. Maybe it's the national media. There have been cases where American teams won a title when their local newspapers were on strike, and not badgering their players with questions. The 1978 New York Yankees are the most notable example.

But in 1950, the Brazilian media were out of control, promoting the team. And the overconfidence became insane. Each player on the winning team gets a winner's medal, but, this time, 22 gold medals were made, with each player's name inscribed on them, before the Final.

A "cup final song" is nothing new in England: Sometimes, both teams in the FA Cup Final will be brought into a recording studio to record one. And the England team usually goes into a studio before leaving for a World Cup to record a song. In 1950, without the players participation, a song was composed, to be played after the Final: "Brasil Os Vencedores" (Brazil the Victors).

Ângelo Mendes de Morais, the Mayor of Rio de Janeiro, met with the players on the morning before the Final, and told them, "You, players, who in less than a few hours will be hailed as Champions by millions of compatriots! You, who have no rivals in the entire Hemisphere! You, who will overcome any other competitor! You, who I already salute as victors!" Even Rimet himself prepared a congratulatory speech for Brazil.

Victory wasn't just expected, it was assumed. As Felix Unger, played by Tony Randall on The Odd Couple, taught us, "You should never assume. Because, when you assume, you make an ASS of U and ME!"

4. Argentina. The other major South American power, though not what they would become in the 1970s, withdrew from the tournament, due to a dispute with the Brazilian Football Confederation. Could they have caused problems for Brazil? Could they have knocked Uruguay out, thus leaving a clearer path for Brazil? We'll never know.

What we do know is that the path for Brazil and Uruguay was clearer than it should have been, and not just because Argentina weren't there to stop either of them:

3. The State of Postwar Europe. Germany was one of the best teams in Europe even before their 1938 Anschluss with Austria, which had done well before that. After it, the Nazi team was even better. And Italy had won the World Cup in 1934 and 1938.

Even with the Superga disaster the year before, which wiped out nearly all of the Torino team that had dominated Italian soccer in the 1940s, Italy would still have been a serious threat to win the 1950 World Cup, as would Germany -- had they been allowed to play.

But Germany was still occupied by the Allied powers. Although both West Germany and East Germany had been established as nations in 1949, the German Football Association (DFB) had only been re-established in January 1950, and wasn't readmitted to FIFA until September, after the World Cup. East Germany's FA wasn't admitted until 1952.

As, officially, still the defending champions after 12 years, Italy were invited to the World Cup without having to go through the qualifying process, and they did play. But they lost to Sweden in their 1st game, and that led to Sweden topping the Group. Italy were out. Perhaps, in a different format, they might have lasted longer, and thus been a bigger threat to win. (And, of course, given the U.S. win over England, and then the Final, this turned out to be only the 3rd-biggest upset of the tournament.)

As for teams in the Soviet sphere: The Soviet Union, 1934 Finalists Czechoslovakia, and 1938 Finalists Hungary did not enter the tournament. All would participate in the qualifying process for the 1954 World Cup, and Hungary reached the Final. But of all of Eastern Europe, only Yugoslavia, whose dictator Josip Tito had had a falling out with the Soviets' Josef Stalin, sent a team to Brazil in 1950.

2. England. If not Brazil, then the best team in the world was probably England. But they choked, as they so often do in major tournaments (rather than simply getting beat by a better team), losing 1-0 to both Spain (somewhat understandable) and the U.S. (understandable only in hindsight, and, even then, it's a bit of a stretch.)

England would have topped their Group had they beaten Spain, regardless of their game against the U.S., and might then have been a threat to win: Spain tied Uruguay 2-2, but got slaughtered by Brazil 6-1. England could have done better than that, but they didn't get the job done.

Who did?

1. Uruguay Were Better. It had been 20 years since the 1930 World Cup win, and none of the players were the same. But some of their 1950 players had been on the team that won the 1942 Copa América, and had reached the Semifinal in 1947. Some would still be on it when they reached the Semifinal in 1953, 1955, 1956, 1957 and 1959, winning it in 1956 and 1959. They also reached the Semifinal of the 1954 World Cup.

Both teams were good in attack. But Uruguay were renowned for their defense, and Brazil were not. If any team was going to beat Brazil in this tournament, it was going to be Uruguay: They didn't have to travel far, they were used to the weather, they were used to the atmosphere, and they were familiar with their opponents. To beat Brazil, they were ready, they were willing, and, clearly, they were able.

VERDICT: Not Guilty. Still, there are old men in Brazil who remember, and pass the story down to children who do not yet know it, who know their country as one that has succeeded at this sport, and not as one with a self-esteem problem.

The legend lives on from Ipanema on down

of the event called Maracanazo.

It's said that the game brought a terrible shame

that can't be erased by a golazo!

No comments:

Post a Comment