I'm not doing trip guides for all the remaining college football teams that I haven't yet done them for -- at least, not this season. I'm doing a few. One of them is Texas A&M, who, last season, gave then-Number 2-ranked Clemson all they could handle before losing 28-26, although they got beaten badly by then-Number 1 Alabama.

Before You Go. It's Texas. It's early in the season. It is likely to be hot and humid. For the opener, they're talking a high of 97, with rain, before cooling off to 76 by gametime. Later in the season, it will get cooler.

College Station is in the Central Time Zone, so you'll be an hour behind New York time. Although Texas was a Confederate State, you won't need to bring your passport or change your money.

Tickets. The Aggies averaged 100,000 fans per home game last season. Okay, it wasn't 100,000. That's an exaggeration. It was only 99,844. Getting tickets will be hard. For the rest of the season, all that's left is the upper deck, where seats are $50.

Getting There. It's 1,647 miles from Times Square in New York to Kyle Field in College Station, Texas. Amtrak does not go to College Station. Nor does Greyhound. So you're probably thinking that you should be flying.

Good luck with that. There is an airport, and you could get a round-trip flight for under $400. But you'd have to change planes in Houston. You're better off flying into Houston, renting a car, and driving the last 105 miles, even though it will cost you close to $1,000 this week.

So, driving it is. You'll be taking Interstate 78 across New Jersey and into Pennsylvania to Harrisburg, where you'll pick up Interstate 81 and take that through the narrow panhandles of Maryland and West Virginia, down the Appalachian spine of Virginia and into Tennessee, where you'll pick up Interstate 40, stay on that briefly until you reach Interstate 75, and take that until you reach Interstate 59, which will take you into Georgia briefly and then across Alabama and Mississippi, and into Louisiana, where you take Interstate 12 west outside New Orleans. Take that until you reach Interstate 10, which you will take to Houston. Once there, Texas Route 6 will get you to College Station.

If you do it right, you should spend about an hour and a half in New Jersey, 3 hours in Pennsylvania, 15 minutes in Maryland, half an hour in West Virginia, 5 and a half hours in Virginia, 3 hours and 45 minutes in Tennessee, half an hour in Georgia, 4 hours in Alabama, 2 hours and 45 minutes in Mississippi, 4 hours and 30 minutes in Louisiana and 4 hours in Texas. Including rest stops, and accounting for traffic, we're talking about a 45-hour trip.

Once In the City. Texas declared its independence from Mexico on March 2, 1836; was admitted to the Union as the 28th State on December 29, 1845; became the 7th State to secede from the Union, on February 1, 1861; and the 10th former Confederate State to be readmitted, on March 30, 1870.

College Station, in Brazos County, is in the middle of the Texas Triangle, formed by the Lone Star State's 3 huge cities: Dallas (177 miles to the north), Houston (96 miles to the southeast) and San Antonio (169 miles to the southwest). Founded in 1860, it's home to about 125,000 permanent residents, not counting A&M students. They break down as 78 percent white, 10 percent Hispanic, 7 percent Asian and 5 percent black.

ZIP Codes run from 77840 to 77845. The Area Code is 979. Utility Customer Services runs the electricity. The Bryan/College Station Eagle is the main daily newspaper. The Brazos Transit District runs the local buses, at $1.50 a ride. There is no "beltway." The intersection of University Drive and Texas Avenue appears to be the centerpoint for addresses. The sales tax in the State of Texas is 6.25 percent.

Because of the school's heavy military influence, I had long thought that the "A&M" in its name stood for "Agricultural and Military." No, like all the others, it stands for "Agricultural and Mechanical," which led to these schools' teams being called the Aggies, even after they may have adopted another name. (The Brazos Valley is sometimes called "Aggieland.")

Some of these later changed their names from "(Name of State) A&M" to "(Name of State) State," including Mississippi State and Oklahoma State. (If you look up college basketball's national champions, you'll see "Oklahoma A&M" as the winners in 1945 and '46. They became Oklahoma State in 1958.) But Texas A&M was not one of them.

It opened in 1876, as The Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas, and was informally known as "Texas A&M" or just "A&M." It took until an act of the State Legislature in 1963 for the name to be changed to "Texas A&M University," with the A and the M no longer standing for anything, being merely symbolic, as the school had long outgrown its land-grant status.

Case in point: Like Rutgers, Penn State, the State University of New York, the University of California, and a few others, but especially their rivals the University of Texas, A&M has several campuses (or should that be "campii"?) around its State. There's a campus in Galveston, devoted to marine research; one in McAllen, devoted to engineering, science and health; and a law school in Fort Worth.

Until 1960, ROTC participation was mandatory. It's now voluntary, but still considered a high honor. As a result, they are considered to be a much more conservative school than UT-Austin. This is reflected in Presidential Libraries: While UT-Austin has that of the very liberal Great Society engineer Lyndon Johnson, A&M has that of oil businessman George H.W. Bush. (George W.'s is as Southern Methodist in Dallas, his wife Laura's alma mater.)

Notable Aggie athletes in sports other than football include:

* Baseball: Rip Collins of the 1930s "Gashouse Gang" St. Louis Cardinals, 1960s Los Angeles Dodger outfielder Wally Moon, 1986 World Series-winning Mets manager Davey Johnson; 1990s Yankee 2nd baseman Chuck Knoblauch; and current Cardinal pitcher Michael Wacha.

* Olympic Gold Medalists: Walt Davis, 1952 high jump; and shot-putters Randy Matson, 1968; Mike Stulce, 1992; and Randy Barnes, 1996.

If you count golf, Bobby Nichols won the 1964 PGA Championship.

Notable A&M graudates in other fields include:

* Entertainment: Actor Rip Torn '52, country singer Lyle Lovett '79, and radio talk show host Neal Boortz '67. (I won't insult the profession of journalism by including him in the next category.

* Journalism: Roland Martin '91.

* Politics, representing Texas unless otherwise stated: Governors Frank White '56 or Arkansas, and Rick Perry '72 (also the current Secretary of Energy); Secretary of Housing & Urban Development Henry Cisneros '68; crazy right-wing Congressman Louie Gohmert '75; and former Presidents Jorge Quiroga-Ramirez of Bolivia and Martin Torrijos of Panama.

* Astronauts: Michael Fossum '80, William Pailes '81, and Steven Swanson '98.

Going In. Kyle Field is in College Station. The mailing address is 756 Houston Street, about a mile and a half south of downtown. Campus buses are available. If you drive in, parking is $25.

The 1st field on the site began hosting football in 1904, on land owned by A&M horticulture professor Edwin Jackson Kyle. He built wooden bleachers that seated 500 people. In 1906, it was named Kyle Field in his honor.

The beginning of the current stadium there was in 1927, with 32,890 seats. It was expanded to 40,000 in 1949, 48,000 in 1967, 54,000 in 1977, 70,000 in 1980, 80,000 in 1999, and was jacked to its current official capacity of 102,733 in 2014. It is the largest stadium in the Southeastern Conference, the 4th-largest stadium in America, and the 5th-largest non-racing stadium in the world. Attendance has, thus far, topped out at 110,633 for a 35-20 Aggie loss to Mississippi on October 11, 2014.

The field runs northwest-to-southeast, and has been natural grass for most of its history, save for 1970 to 1995, when it was AstroTurf. The North End is named the Bernard C. Richardson Zone, for its funder, a 1941 graduate and oil executive. It houses the Texas A&M Sports Museum.

An October 6, 2017 Thrillist article ranked Kyle Field 14th among the country's top college football stadiums, citing its great atmosphere. One thing to be careful of, though: Its upper deck is considered one of the steepest in college football.

Food. Being in a "Wild West" State, you might expect A&M to have Western-themed stands with "real American food" at its stadium. Being in a Southern State, you might also expect to have barbecue. However, if you expect a concessions stand map on their website, you'll be disappointed. About all it says is that Levy Restaurants, a familiar name, is their official concessionaire, and that stands are located throughout the stadium.

Team History Displays. The Ford Hall of Champions is on the west side of the stadium, featuring exhibits and interactive displays about Aggie football history.

Texas A&M claims 3 National Championships, but all were long ago, and only the last, 1939, was in the era of national polls, in their case the Associated Press (AP, the sportswriters' poll). They were retroactively awarded shares of the National Championship in 1919 and 1927.

They won 17 Southwest Conference Championships before that league folded following the 1995-96 schoolyear: 1917, 1919, 1921, 1925, 1927, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1956, 1967, 1975, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1991, 1992 and 1993. They moved to the Big 12 Conference, and won that league's title in 1998. They also won the Big 12 South Division in 1997 and 2010. Since 2012, they have played in the Southeastern Conference, but have yet to win the West Division title, let alone the overall SEC Championship. The Championship Wall stands outside the north end.

They have no retired numbers. Well, one, sort of. I'll get to that later. They have had 11 players so far be elected to the College Football Hall of Fame: 1900s halfback Joe Utay, 1920s halfback Joel Hunt, 1930s guard Joe Routt, 1930s fullback John Kimbrough, 1950s running backs Jack Pardee and John David Crow, 1950s offensive tackle Charlie Krueger, 1960s safety Dave Elmendorf, 1970s defensive end Jacob Green, 1980s defensive tackle Ray Childress and 1990s linebacker Dat Nguyen. 1950s safety Yale Lary is not in the College Football Hall of Fame, but he is in the Pro Football Hall.

Six of A&M's head coaches are in the College Football Hall, but mainly for what they did elsewhere: Dana Xenophon Bible, 1917-28 (better known for what he did at Nebraska and, much worse from A&M's perspective, Texas); Matty Bell, 1929-33 (SMU); Paul "Bear" Bryant, 1954-57 (Alabama); and Gene Stallings, 1965-71 (Alabama, one of the Bear's "Junction Boys" in 1954, and later one of his 'Bama assistants). Only Homer Norton, 1934-47, and Richard Copeland "R.C." Slocum, 1982-2002, were elected specifically for coaching A&M.

Crow won the Heisman Trophy in 1957, had a good career with the NFL's Chicago/St. Louis Cardinals, and later served as A&M's athletic director. Oddly, for all that Bryant achieved as a coach, Crow was his only Heisman winner, and was not at Alabama. In 2012, quarterback Johnny Manziel became the Aggies' 2nd Heisman winner.

Lots of football teams, at all levels, look at their fans, supporting the 11 men on the field, as "The 12th Man." Texas A&M raises this to the level of an art form. Sometimes an absurdist art form. And it all goes back to an "original 12th man."

On January 2, 1922, Texas A&M played Centre College in the Dixie Classic in Dallas, an unofficial forerunner to the Cotton Bowl. It was the 1st postseason game ever played in the Southwest. Coach Dana Bible saw his team, already thinned by injuries, lose more men. He walked over to the Aggie student section, and called for E. King Gill. Gill, a Dallas native, had quit the football team to play basketball, but agreed to return, and suit up. (This would not have been allowed under today's rules.)

Bible did not put Gill into the game, and he wasn't needed, as A&M won 22-14. Gill later said, "I wish I could say that I went in and ran for the winning touchdown but I did not. I simply stood buy in case my team needed me." But Gill's readiness to play symbolized the love of the Aggies by all students. and the student body has thought of itself as The 12th Man ever since. There is a statue outside the stadium, showing 12 students, some of them women, under a sign saying, "HOME OF THE 12TH MAN." The 12th Man thing is so ingrained, even their website is 12thman.com.

Perhaps appropriately, given the circumstances in which he was called, Earl King Gill became a physician, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas, until his death in 1974. A statue of him now stands at the northeast corner of Kyle Field.

In the 1980s, Jackie Sherrill was the head coach, and he created the 12th Man Squad, composed solely of walk-on players, used only for kickoffs, and each one wore Number 12. R.C. Slocum succeeded Sherrill, and cut this back, yet extended it at the same time: He chose one walk-on player every week who had distinguished himself in practice, and gave him the Number 12 jersey, and put him on special teams. His successors have continued this.

As I said, the Texas A&M Sports Museum, honoring athletes in all sports, is in the north end of Kyle Field, inside the Bernard C. Richardson Zone.

The rivalry with the University of Texas, 106 miles to the west in Austin? If football is a religion in that State, then this was a holy war. This goes beyond the late, great ABC Sports announcer Keith Jackson's line, "These two teams just... don't... like each other."

How much do they hate each other? Each mentions the other in their fight song. The Aggies hate the Longhorns more: While the 'Horns merely sing, "And it's Goodbye to A&M" in "Texas Fight" -- much like Georgia Tech sings "To hell with Georgia" in "Ramblin' Wreck Fro Georgia Tech" -- the entire 2nd verse of "The Aggie War Hymn" is about hating the University of Texas.

The game with Texas A&M was usually played on Thanksgiving Weekend, with 63 of the 118 meetings taking place on Thanksgiving Day itself. They began playing in 1894, and the game was frequently nasty as hell. To a Texas Longhorn, A&M is a rural school, a "cow college," full of gung-ho rednecks. To a Texas Aggie, the Longhorns are effete intellectuals with more money than sense. There's a political aspect, too: The Longhorns are called "tea-sippin' liberals," too good for American and Texan values and good ole whiskey.

The rivalry even worked its way to Broadway and Hollywood. In 1978, the musical The Best Little Whorehouse In Texas premiered, and according to "The Aggie Song," when A&M beats UT-Austin, the players are invited to the titular brothel, located in fictional Gilbert: "Twenty-two miles to the Chicken Ranch, where memories and Aggie boys are made!" A movie was made in 1982, with Burt Reynolds and Dolly Parton. (The story was mostly true: The real Chicken Ranch was in LaGrange, considerably further from Kyle Field, about 70 miles, and was closed down thanks to a nosy reporter in 1973.)

The rivalry included Aggie Bonfire. From 1909 onward, it was held on the Simpson Drill Field, on the other side of the bookstore from the stadium, every year on the night before the game against the Longhorns, symbolizing their "burning desire to beat the hell out of TU." In 1969, they set a world record for largest bonfire.

In 1999, it collapsed during construction, killing 12 people and injuring 27 others. The two schools put aside their differences for various memorials and tributes. The Bonfire was resumed in 2002, and lasted for the length of the rivalry.

A&M went from the SWC to the Big 12 with Texas in 1996, but left for the SEC in 2012. A last-second field goal gave the Longhorns a 27-25 win in what is currently the most recent meeting, on November 24, 2011. To keep the rivalry going, the schools agreed to establish the Lone Star Trophy, given to the school with the most wins against the other in other sports. In football, the Longhorns lead 76-37-5. With both schools' nonconference schedules in place through the 2023 season, the rivalry will not be revived before then.

In 1992, John Maher and Kirk Bohls published a book about being a Longhorn fan, titled Bleeding Orange. But this was a response to a book that Frank W. Cox III had published earlier in the year, about being an Aggie fan: I Bleed Maroon. More recently, Homer Jacobs published The Pride of Aggieland: Spirit and Football at a Place Like No Other in 2002. A video about the 'Horns-Aggies rivalry, Lone Star Holy War, is available. So is the Kyle Field entry in the Fields of Glory series.

During the Game. This is Texas. What's more, this is Texas A&M. Whatever level of respect you show will be returned. In other words, don't say anything unkind about any aspect of the school or the State, and don't say anything kind about the Longhorns, and you should be okay.

Before each home game, Midnight Yell takes place at midnight inside Kyle Field. For away games, they hold a Yell Practice (not at midnight) on the Quadrangle on the south side of campus.

The Fightin' Texas Aggie Band plays "The Fightin' Texas Aggie War Hymn" (the fight song), "The Spirit of Aggieland" (the alma mater), a march tune titled "The Noble Men of Kyle" (which is also a nickname for the band), and, as you might expect, given the school's military background, the Civil War song "When Johnny Comes Marching Home," "The Stars and Stripes Forever," "The Ballad of the Green Berets," the theme from the 1970 film Patton, and a medley of the branches' theme songs: "The U.S. Field Artillery March" (a.k.a. "As the Caissons Go Rolling Along"), "Anchors Aweigh," "The Wild Blue Wonder" and "The Marine Hymn" (a.k.a. "From the Halls of Montezuma").

They also execute a block T, a block A and M, and a maneuver called "The Maroon Tattoo," forming a giant X. When the band got their first computers, this formation was programmed in, and the computer said it was physically impossible to perform. Well, it must be possible, since they'd already been doing it for years, and they continue to do it.

In their 1982 College Football Preview Issue, Sports Illustrated had lists of bests and worsts in college football. For "Worst Cheerleaders," they said, "Texas A&M's. All guys." And they weren't cheerleaders, they were Yell Leaders. Fortunately, they now have a separate all-female cheerleading squad to go with their all-male Yell Leaders.

Since 1931, A&M's mascots have been a series of dogs named Reveille. Always a female, and always address by a student as "Miss Rev, Ma'am," she is the highest-ranking member of their Corps of Cadets. Since the adoption of Reveille III in 1966, they have all been purebred collies.

Like the University of Georgia with their Uga the Bulldogs, when the Reveilles die, they are buried with military honors inside the stadium, at the north end of Kyle Field, in view of the south end scoreboard.

The current holder of the role is Reveille IX, in service since 2015. She is the only dog on campus, other than service animals, that is permitted to enter any campus building. If she decides to sleep on a cadet's bed, that cadet must sleep on the floor that night. If she is taken into a class, and barks during that session, that session is immediately canceled. She has her own student ID card, and her own cell phone, operated by her caretaker.

Since 1985, A&M fans have waved white 12th Man Towels, much like Pittsburgh Steeler fans and their Terrible Towels and Minnesota Twin fans and their Homer Hankies.

After the Game. College Station is a small, comparatively low-crime city, and as long as you behave yourself, the locals will probably behave themselves, win or lose.

To get something to eat after the game, you'll have a bit of a walk from Kyle Field. There are notable local eateries and bars, and chain restaurants, to the north on University Drive and College Avenue, and to the east on Texas Avenue and George Bush Drive.

If your visit to College Station is during the European soccer season (which is once again underway), you may be out of luck, unless you head to Austin or Houston.

Sidelights. Reed Arena, A&M's 12,989-seat basketball venue, opened in 1998. It was named for Chester J. Reed '47, whose donations made it possible. 730 Olsen Blvd., 2 blocks west of Kyle Field.

A&M was long far more successful in football than in basketball, but their basketball team has gotten better recently. They won the 2016 SEC regular season title, after winning it 11 times in the SWC. They won 2 SWC Tournaments, in 1980 and 1987. The closest they've come to a National Championship is 6 visits to the Sweet 16, including in 2016 and 2018.

As I said earlier, the big cities of Texas are far: Houston is 96 miles to the southeast, Austin 106 miles to the west, San Antonio 169 miles to the southwest, and Dallas 177 miles to the north. The closest NHL team is the Dallas Stars, and the closest teams in all the other sports are in Houston. Even the closest minor-league baseball team is further away than the Houston Astros.

College Station has a few museums. The Museum of the American GI is at 19124 Texas Route 6, about 10 miles southeast of downtown. And the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum is at 1000 George Bush Drive West, about 2 miles west of downtown. With the deaths of first Barbara Bush, then the 41st President, in 2018, both were buried at the Library.

*

Texas can be hot, but Texas A&M is a great place to watch a college football game. Best of all, it's not Dallas. So there can be a good old time in the hot town tonight.

Houston, and South Texas, have had some racial disturbances. On August 13, 1906, in Brownsville on the Rio Grande (the border between Texas and Mexico), a white bartender was killed and a Hispanic policeman was wounded by gunshots. The blame fell on a segregated unit of black soldiers at nearby Fort Brown.

Following a U.S. Army Inspector General's report, President Theodore Roosevelt, in his role as Commander-in-Chief, ordered dishonorable discharges for 167 of those soldiers, costing them pensions and the right to serve in federal service jobs. This is a blot on TR's record, and in 1972, President Richard Nixon pardoned them and rewrote their discharges as honorable.

There were 21 deaths in a riot in Houston on August 23, 1917, when members of the all-black 24th United States Infantry Regiment at Camp Logan fought back against the all-white Houston Police Department. After a series of courts-martial that could only have been a kangaroo court, there were 19 executions, and 41 soldiers were sentenced to life imprisonment.

There was a race riot in Beaumont, about 85 miles east of Houston, on June 15, 1943, with 3 deaths. On May 17, 1967, there was a riot on the campus of the historically-black Texas Southern University, leading to the death of a police officer and the arrests of 500 students. But once it was found that the officer had died from "friendly fire," the ricochet of a fellow officer's bullet, all charges against the students were dropped. And there was a race riot in the Moody Park neighborhood of north Houston on May 7, 1978, with no deaths.

Because of the school's heavy military influence, I had long thought that the "A&M" in its name stood for "Agricultural and Military." No, like all the others, it stands for "Agricultural and Mechanical," which led to these schools' teams being called the Aggies, even after they may have adopted another name. (The Brazos Valley is sometimes called "Aggieland.")

Some of these later changed their names from "(Name of State) A&M" to "(Name of State) State," including Mississippi State and Oklahoma State. (If you look up college basketball's national champions, you'll see "Oklahoma A&M" as the winners in 1945 and '46. They became Oklahoma State in 1958.) But Texas A&M was not one of them.

It opened in 1876, as The Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas, and was informally known as "Texas A&M" or just "A&M." It took until an act of the State Legislature in 1963 for the name to be changed to "Texas A&M University," with the A and the M no longer standing for anything, being merely symbolic, as the school had long outgrown its land-grant status.

Case in point: Like Rutgers, Penn State, the State University of New York, the University of California, and a few others, but especially their rivals the University of Texas, A&M has several campuses (or should that be "campii"?) around its State. There's a campus in Galveston, devoted to marine research; one in McAllen, devoted to engineering, science and health; and a law school in Fort Worth.

Until 1960, ROTC participation was mandatory. It's now voluntary, but still considered a high honor. As a result, they are considered to be a much more conservative school than UT-Austin. This is reflected in Presidential Libraries: While UT-Austin has that of the very liberal Great Society engineer Lyndon Johnson, A&M has that of oil businessman George H.W. Bush. (George W.'s is as Southern Methodist in Dallas, his wife Laura's alma mater.)

Notable Aggie athletes in sports other than football include:

* Baseball: Rip Collins of the 1930s "Gashouse Gang" St. Louis Cardinals, 1960s Los Angeles Dodger outfielder Wally Moon, 1986 World Series-winning Mets manager Davey Johnson; 1990s Yankee 2nd baseman Chuck Knoblauch; and current Cardinal pitcher Michael Wacha.

* Olympic Gold Medalists: Walt Davis, 1952 high jump; and shot-putters Randy Matson, 1968; Mike Stulce, 1992; and Randy Barnes, 1996.

If you count golf, Bobby Nichols won the 1964 PGA Championship.

Notable A&M graudates in other fields include:

* Entertainment: Actor Rip Torn '52, country singer Lyle Lovett '79, and radio talk show host Neal Boortz '67. (I won't insult the profession of journalism by including him in the next category.

* Journalism: Roland Martin '91.

* Politics, representing Texas unless otherwise stated: Governors Frank White '56 or Arkansas, and Rick Perry '72 (also the current Secretary of Energy); Secretary of Housing & Urban Development Henry Cisneros '68; crazy right-wing Congressman Louie Gohmert '75; and former Presidents Jorge Quiroga-Ramirez of Bolivia and Martin Torrijos of Panama.

* Astronauts: Michael Fossum '80, William Pailes '81, and Steven Swanson '98.

Going In. Kyle Field is in College Station. The mailing address is 756 Houston Street, about a mile and a half south of downtown. Campus buses are available. If you drive in, parking is $25.

The 1st field on the site began hosting football in 1904, on land owned by A&M horticulture professor Edwin Jackson Kyle. He built wooden bleachers that seated 500 people. In 1906, it was named Kyle Field in his honor.

The beginning of the current stadium there was in 1927, with 32,890 seats. It was expanded to 40,000 in 1949, 48,000 in 1967, 54,000 in 1977, 70,000 in 1980, 80,000 in 1999, and was jacked to its current official capacity of 102,733 in 2014. It is the largest stadium in the Southeastern Conference, the 4th-largest stadium in America, and the 5th-largest non-racing stadium in the world. Attendance has, thus far, topped out at 110,633 for a 35-20 Aggie loss to Mississippi on October 11, 2014.

1970s configuration

The field runs northwest-to-southeast, and has been natural grass for most of its history, save for 1970 to 1995, when it was AstroTurf. The North End is named the Bernard C. Richardson Zone, for its funder, a 1941 graduate and oil executive. It houses the Texas A&M Sports Museum.

An October 6, 2017 Thrillist article ranked Kyle Field 14th among the country's top college football stadiums, citing its great atmosphere. One thing to be careful of, though: Its upper deck is considered one of the steepest in college football.

Food. Being in a "Wild West" State, you might expect A&M to have Western-themed stands with "real American food" at its stadium. Being in a Southern State, you might also expect to have barbecue. However, if you expect a concessions stand map on their website, you'll be disappointed. About all it says is that Levy Restaurants, a familiar name, is their official concessionaire, and that stands are located throughout the stadium.

Team History Displays. The Ford Hall of Champions is on the west side of the stadium, featuring exhibits and interactive displays about Aggie football history.

Texas A&M claims 3 National Championships, but all were long ago, and only the last, 1939, was in the era of national polls, in their case the Associated Press (AP, the sportswriters' poll). They were retroactively awarded shares of the National Championship in 1919 and 1927.

They won 17 Southwest Conference Championships before that league folded following the 1995-96 schoolyear: 1917, 1919, 1921, 1925, 1927, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1956, 1967, 1975, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1991, 1992 and 1993. They moved to the Big 12 Conference, and won that league's title in 1998. They also won the Big 12 South Division in 1997 and 2010. Since 2012, they have played in the Southeastern Conference, but have yet to win the West Division title, let alone the overall SEC Championship. The Championship Wall stands outside the north end.

They have no retired numbers. Well, one, sort of. I'll get to that later. They have had 11 players so far be elected to the College Football Hall of Fame: 1900s halfback Joe Utay, 1920s halfback Joel Hunt, 1930s guard Joe Routt, 1930s fullback John Kimbrough, 1950s running backs Jack Pardee and John David Crow, 1950s offensive tackle Charlie Krueger, 1960s safety Dave Elmendorf, 1970s defensive end Jacob Green, 1980s defensive tackle Ray Childress and 1990s linebacker Dat Nguyen. 1950s safety Yale Lary is not in the College Football Hall of Fame, but he is in the Pro Football Hall.

Six of A&M's head coaches are in the College Football Hall, but mainly for what they did elsewhere: Dana Xenophon Bible, 1917-28 (better known for what he did at Nebraska and, much worse from A&M's perspective, Texas); Matty Bell, 1929-33 (SMU); Paul "Bear" Bryant, 1954-57 (Alabama); and Gene Stallings, 1965-71 (Alabama, one of the Bear's "Junction Boys" in 1954, and later one of his 'Bama assistants). Only Homer Norton, 1934-47, and Richard Copeland "R.C." Slocum, 1982-2002, were elected specifically for coaching A&M.

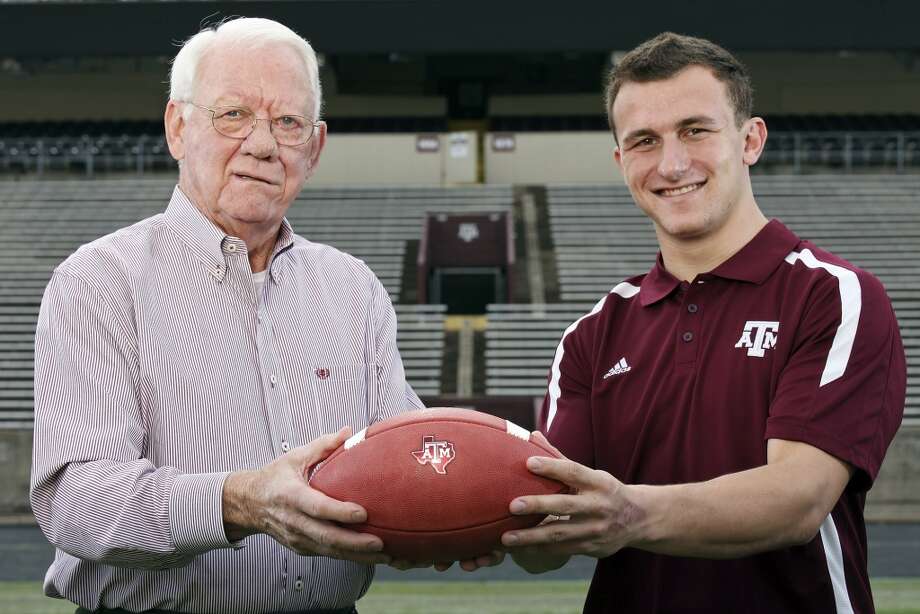

Crow won the Heisman Trophy in 1957, had a good career with the NFL's Chicago/St. Louis Cardinals, and later served as A&M's athletic director. Oddly, for all that Bryant achieved as a coach, Crow was his only Heisman winner, and was not at Alabama. In 2012, quarterback Johnny Manziel became the Aggies' 2nd Heisman winner.

Crow and Manziel

Lots of football teams, at all levels, look at their fans, supporting the 11 men on the field, as "The 12th Man." Texas A&M raises this to the level of an art form. Sometimes an absurdist art form. And it all goes back to an "original 12th man."

On January 2, 1922, Texas A&M played Centre College in the Dixie Classic in Dallas, an unofficial forerunner to the Cotton Bowl. It was the 1st postseason game ever played in the Southwest. Coach Dana Bible saw his team, already thinned by injuries, lose more men. He walked over to the Aggie student section, and called for E. King Gill. Gill, a Dallas native, had quit the football team to play basketball, but agreed to return, and suit up. (This would not have been allowed under today's rules.)

Bible did not put Gill into the game, and he wasn't needed, as A&M won 22-14. Gill later said, "I wish I could say that I went in and ran for the winning touchdown but I did not. I simply stood buy in case my team needed me." But Gill's readiness to play symbolized the love of the Aggies by all students. and the student body has thought of itself as The 12th Man ever since. There is a statue outside the stadium, showing 12 students, some of them women, under a sign saying, "HOME OF THE 12TH MAN." The 12th Man thing is so ingrained, even their website is 12thman.com.

Perhaps appropriately, given the circumstances in which he was called, Earl King Gill became a physician, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas, until his death in 1974. A statue of him now stands at the northeast corner of Kyle Field.

In the 1980s, Jackie Sherrill was the head coach, and he created the 12th Man Squad, composed solely of walk-on players, used only for kickoffs, and each one wore Number 12. R.C. Slocum succeeded Sherrill, and cut this back, yet extended it at the same time: He chose one walk-on player every week who had distinguished himself in practice, and gave him the Number 12 jersey, and put him on special teams. His successors have continued this.

As I said, the Texas A&M Sports Museum, honoring athletes in all sports, is in the north end of Kyle Field, inside the Bernard C. Richardson Zone.

The rivalry with the University of Texas, 106 miles to the west in Austin? If football is a religion in that State, then this was a holy war. This goes beyond the late, great ABC Sports announcer Keith Jackson's line, "These two teams just... don't... like each other."

How much do they hate each other? Each mentions the other in their fight song. The Aggies hate the Longhorns more: While the 'Horns merely sing, "And it's Goodbye to A&M" in "Texas Fight" -- much like Georgia Tech sings "To hell with Georgia" in "Ramblin' Wreck Fro Georgia Tech" -- the entire 2nd verse of "The Aggie War Hymn" is about hating the University of Texas.

The game with Texas A&M was usually played on Thanksgiving Weekend, with 63 of the 118 meetings taking place on Thanksgiving Day itself. They began playing in 1894, and the game was frequently nasty as hell. To a Texas Longhorn, A&M is a rural school, a "cow college," full of gung-ho rednecks. To a Texas Aggie, the Longhorns are effete intellectuals with more money than sense. There's a political aspect, too: The Longhorns are called "tea-sippin' liberals," too good for American and Texan values and good ole whiskey.

The rivalry even worked its way to Broadway and Hollywood. In 1978, the musical The Best Little Whorehouse In Texas premiered, and according to "The Aggie Song," when A&M beats UT-Austin, the players are invited to the titular brothel, located in fictional Gilbert: "Twenty-two miles to the Chicken Ranch, where memories and Aggie boys are made!" A movie was made in 1982, with Burt Reynolds and Dolly Parton. (The story was mostly true: The real Chicken Ranch was in LaGrange, considerably further from Kyle Field, about 70 miles, and was closed down thanks to a nosy reporter in 1973.)

The rivalry included Aggie Bonfire. From 1909 onward, it was held on the Simpson Drill Field, on the other side of the bookstore from the stadium, every year on the night before the game against the Longhorns, symbolizing their "burning desire to beat the hell out of TU." In 1969, they set a world record for largest bonfire.

In 1999, it collapsed during construction, killing 12 people and injuring 27 others. The two schools put aside their differences for various memorials and tributes. The Bonfire was resumed in 2002, and lasted for the length of the rivalry.

A&M went from the SWC to the Big 12 with Texas in 1996, but left for the SEC in 2012. A last-second field goal gave the Longhorns a 27-25 win in what is currently the most recent meeting, on November 24, 2011. To keep the rivalry going, the schools agreed to establish the Lone Star Trophy, given to the school with the most wins against the other in other sports. In football, the Longhorns lead 76-37-5. With both schools' nonconference schedules in place through the 2023 season, the rivalry will not be revived before then.

With the move to the SEC, A&M's rivals are now neighboring schools like Arkansas (another former SWC team) and Louisiana State. On November 24, 2018, A&M and LSU played the longest game in NCAA history, going 7 overtimes before A&M finally won 74-72.

Stuff. In spite of its immense size, Kyle Field does not have a team store, just souvenir stands. But you won't have to go too far to get anything you'd want: The University Bookstore, a.k.a. the 12th Man Shop, is across from the northeast corner of Kyle Field (and the King Gill statue), at 275 Joe Routt Blvd.

In 1992, John Maher and Kirk Bohls published a book about being a Longhorn fan, titled Bleeding Orange. But this was a response to a book that Frank W. Cox III had published earlier in the year, about being an Aggie fan: I Bleed Maroon. More recently, Homer Jacobs published The Pride of Aggieland: Spirit and Football at a Place Like No Other in 2002. A video about the 'Horns-Aggies rivalry, Lone Star Holy War, is available. So is the Kyle Field entry in the Fields of Glory series.

During the Game. This is Texas. What's more, this is Texas A&M. Whatever level of respect you show will be returned. In other words, don't say anything unkind about any aspect of the school or the State, and don't say anything kind about the Longhorns, and you should be okay.

Before each home game, Midnight Yell takes place at midnight inside Kyle Field. For away games, they hold a Yell Practice (not at midnight) on the Quadrangle on the south side of campus.

The Fightin' Texas Aggie Band plays "The Fightin' Texas Aggie War Hymn" (the fight song), "The Spirit of Aggieland" (the alma mater), a march tune titled "The Noble Men of Kyle" (which is also a nickname for the band), and, as you might expect, given the school's military background, the Civil War song "When Johnny Comes Marching Home," "The Stars and Stripes Forever," "The Ballad of the Green Berets," the theme from the 1970 film Patton, and a medley of the branches' theme songs: "The U.S. Field Artillery March" (a.k.a. "As the Caissons Go Rolling Along"), "Anchors Aweigh," "The Wild Blue Wonder" and "The Marine Hymn" (a.k.a. "From the Halls of Montezuma").

They also execute a block T, a block A and M, and a maneuver called "The Maroon Tattoo," forming a giant X. When the band got their first computers, this formation was programmed in, and the computer said it was physically impossible to perform. Well, it must be possible, since they'd already been doing it for years, and they continue to do it.

In their 1982 College Football Preview Issue, Sports Illustrated had lists of bests and worsts in college football. For "Worst Cheerleaders," they said, "Texas A&M's. All guys." And they weren't cheerleaders, they were Yell Leaders. Fortunately, they now have a separate all-female cheerleading squad to go with their all-male Yell Leaders.

Like the University of Georgia with their Uga the Bulldogs, when the Reveilles die, they are buried with military honors inside the stadium, at the north end of Kyle Field, in view of the south end scoreboard.

The current holder of the role is Reveille IX, in service since 2015. She is the only dog on campus, other than service animals, that is permitted to enter any campus building. If she decides to sleep on a cadet's bed, that cadet must sleep on the floor that night. If she is taken into a class, and barks during that session, that session is immediately canceled. She has her own student ID card, and her own cell phone, operated by her caretaker.

Reveille IX in her usual bed, apparently sometime around Halloween

Since 1985, A&M fans have waved white 12th Man Towels, much like Pittsburgh Steeler fans and their Terrible Towels and Minnesota Twin fans and their Homer Hankies.

After the Game. College Station is a small, comparatively low-crime city, and as long as you behave yourself, the locals will probably behave themselves, win or lose.

To get something to eat after the game, you'll have a bit of a walk from Kyle Field. There are notable local eateries and bars, and chain restaurants, to the north on University Drive and College Avenue, and to the east on Texas Avenue and George Bush Drive.

If your visit to College Station is during the European soccer season (which is once again underway), you may be out of luck, unless you head to Austin or Houston.

Sidelights. Reed Arena, A&M's 12,989-seat basketball venue, opened in 1998. It was named for Chester J. Reed '47, whose donations made it possible. 730 Olsen Blvd., 2 blocks west of Kyle Field.

A&M was long far more successful in football than in basketball, but their basketball team has gotten better recently. They won the 2016 SEC regular season title, after winning it 11 times in the SWC. They won 2 SWC Tournaments, in 1980 and 1987. The closest they've come to a National Championship is 6 visits to the Sweet 16, including in 2016 and 2018.

As I said earlier, the big cities of Texas are far: Houston is 96 miles to the southeast, Austin 106 miles to the west, San Antonio 169 miles to the southwest, and Dallas 177 miles to the north. The closest NHL team is the Dallas Stars, and the closest teams in all the other sports are in Houston. Even the closest minor-league baseball team is further away than the Houston Astros.

College Station has a few museums. The Museum of the American GI is at 19124 Texas Route 6, about 10 miles southeast of downtown. And the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum is at 1000 George Bush Drive West, about 2 miles west of downtown. With the deaths of first Barbara Bush, then the 41st President, in 2018, both were buried at the Library.

*

Texas can be hot, but Texas A&M is a great place to watch a college football game. Best of all, it's not Dallas. So there can be a good old time in the hot town tonight.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/46833404/image1.0.0.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment