NOTE: This is adapted from a piece I wrote in 2013, upon the release of the film 42, about Jackie's 1947 season: "42 Things You Should Know About Jackie Robinson."

The strike did not happen, and the Cards ended up finishing a close 2nd to the Dodgers. The Cards would do so again in 1949, and then their 1940s dynasty got old. They didn't integrate until 1954, with Tom Alston. Not until they had a much bigger black representation, with Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, Bill White and Curt Flood leading the way, did they win another Pennant, in 1964.

In addition to Robinson with the Dodgers, Jethroe with the Braves, Alston with the Cardinals and Howard with the Yankees in 1955, the following were the first black players on each team:

On April 15, 1997, a ceremony honoring the 50th Anniversary of Jackie's debut was held at Shea Stadium in New York, during a game between the Mets and the Los Angeles edition of the Dodgers. Reese, then dying of cancer, could not attend. But several of his teammates did, including Newcombe, Snider, and Koufax -- who wore a Mets cap in honor of his classmate at Brooklyn's Lafayette High School, Met owner Fred Wilpon. Rachel, Sharon and David attended, as did President Bill Clinton.

So did I: I won 2 tickets in a radio contest, and, knowing I'd never be able to live with myself if I didn't, took my Grandma, and together we were part of a sellout crowd of 54,047 paying tribute to the man who was her all-time hero in life, not just in sports.

Commissioner Bud Selig announced an unprecedented honor: Number 42 would be retired through all of baseball, the major leagues and the minors alike. All players still wearing the number would get to keep it, including the Mets' Butch Huskey, the Red Sox' Mo Vaughn, and the man who, in 2013, left the field for the last time as the last player who will ever wear it as his own number, Mariano Rivera of the Yankees. (Each year, on April 15, starting on the 60th Anniversary in 2007, every player wears Number 42.) Not that it matters, but the Mets beat the Dodgers, 5-0. The home plate umpire was a black man, Eric Gregg.

Although Grandma went to a few Lakewood BlueClaws games when that team was established, she never went to another major league game. Her last experience at a Major League Baseball game was her favorite. And, through a stroke of luck with a radio station, I was able to bring it to her.

Jackie Robinson made my Grandma happy that night, 25 years after his death. Even 47 years after his death, and 100 years after his birth, he is still making an impact. And there's not many people about whom we can say that.

Mallie Robinson was a single mother. Later in 1919, her husband, Jerry, the son of a former slave, ran off with another woman. This left Mallie to raise 5 children: In order, son Edgar, son Frank, son Matthew, daughter Willa Mae, son Jack. She sure wasn't going to raise those 5 children in the segregated South. Her brother Burton lived in Pasadena, California, outside Los Angeles, so she moved herself and her children there.

What Jackie Robinson would have been like if he'd grown up under segregation, we may never know. However, it has been speculated that one of the reasons Bill Russell led the Boston Celtics to all those NBA titles, while Wilt Chamberlain, on his various teams, only won 2, was that Wilt grew up in a mixed neighborhood in West Philadelphia, where he was mostly treated as an equal, and grew up happy; while Russell was a child in segregated Louisiana before moving to Oakland.

What Jackie Robinson would have been like if he'd grown up under segregation, we may never know. However, it has been speculated that one of the reasons Bill Russell led the Boston Celtics to all those NBA titles, while Wilt Chamberlain, on his various teams, only won 2, was that Wilt grew up in a mixed neighborhood in West Philadelphia, where he was mostly treated as an equal, and grew up happy; while Russell was a child in segregated Louisiana before moving to Oakland.

(This was a path several other Southern athletes in the making took: Frank Robinson, Curt Flood, Willie Stargell and Joe Morgan were all boys in Texas and teenagers in Oakland.)

A Jackie Robinson growing up in Georgia might have had a chip on his shoulder -- or, if you think he already had one, a bigger one.

As a boy, Jackie Robinson was in a gang. Hard to believe? It was called the Pepper Street Gang, and it had black, Mexican and Japanese kids -- pretty much everything Pasadena had, except whites. All were poor, and stood up for each other. Eventually, Jackie left it.

Jackie's brother, Matthew MacKenzie Robinson, a.k.a. Mack, was the first great athlete in the family. He attended Pasadena City College, a junior college, and then moved on to the University of Oregon. His sport was track and field, and he made the U.S. Olympic team in 1936, winning a Silver Medal in the 200 meters in Berlin. He wasn't going to win the Gold Medal because Jesse Owens was the best track performer in the world at the time.

Mack set the world record in the long jump, and later faced down his family's past by becoming an activist against street crime in Pasadena. He raised money for a statue of Jackie outside UCLA's baseball stadium, which is named for Jackie. He died in 2000, at the age of 85.

Jackie followed Mack to Pasadena City, and moved on to the University of California at Los Angeles. His best sport was football, and was one of the best running backs on the West Coast. His next-best sport was basketball, although this was before John Wooden arrived at UCLA and they started winning all those National Championships. Baseball was only his 3rd-best sport. He also played tennis there -- a rarity for black people at the time -- and became the first 4-sport letterman in UCLA history.

He did not graduate from UCLA, leaving with one semester to go, because he had used up all his athletic ability. But the fact that he had played on, and against, integrated teams proved to be very important later on.

It was at UCLA in 1941 that Jackie met Rachel Isum, 3 years younger and a nursing student. They were engaged in 1943, and married in 1946. The fact that Jackie was engaged when Branch Rickey contacted him was also crucial.

Jackie had the idea of becoming a teacher, coach, and/or athletic director at a high school for black kids. But first, like a lot of college athletes, he didn't want to be done with sports. The minor-league Honolulu Bears needed baseball players, and he played there for a while. He got on a ship at Honolulu's Pearl Harbor on December 5, 1941, intending to play football for the minor-league Los Angeles Bulldogs. Two days later, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, putting the kibosh on Jackie's plans.

By the time that Jackie's ship reached California, war had been declared. He enlisted, and while he was at Fort Riley in Kansas (where later baseball star Johnny Damon was born), he and some other black soldiers applied to Officers' Candidate School. They waited for 3 months without hearing if they were accepted.

Heavyweight Champion Joe Louis was transferred to Fort Riley, and these soldiers told him what was happening -- or, rather, what was not happening. Joe made some calls, and the black soldiers were accepted as 2nd Lieutenants.

Lt. Jack Robinson was assigned to the 761st Tank Battalion, an all-black unit known as the Black Panthers, headquartered at Fort Hood, in the segregated State of Texas. There, he became the Rosa Parks of the U.S. Army. Seriously. And this was 11 years before anybody ever heard of Rosa Parks.

On July 6, 1944, Lt. Robinson boarded an Army bus. The driver ordered him to move to the back of the bus. He refused. The driver seemed to let it go, but upon arriving at Fort Hood, he told the military police, and they arrested Jackie. Jackie was court-martialed for insubordination.

This prevented him from being sent overseas with the 761st, meaning he never saw combat. An all-white panel of 9 officers acquitted him of the charges, since the Army is a federal government institution, and federal law supersedes State law, and thus the driver had no authority to order him to the back of the bus.

So even if Jackie had never played professional sports, he still had a story that had to be told. And it was: In 1990, Andre Braugher starred in the TV-movie The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson, with Ruby Dee playing Jackie's mother -- 40 years after she'd played Rachel in The Jackie Robinson Story, in which Jackie played himself.

As a boy, Jackie Robinson was in a gang. Hard to believe? It was called the Pepper Street Gang, and it had black, Mexican and Japanese kids -- pretty much everything Pasadena had, except whites. All were poor, and stood up for each other. Eventually, Jackie left it.

Jackie's brother, Matthew MacKenzie Robinson, a.k.a. Mack, was the first great athlete in the family. He attended Pasadena City College, a junior college, and then moved on to the University of Oregon. His sport was track and field, and he made the U.S. Olympic team in 1936, winning a Silver Medal in the 200 meters in Berlin. He wasn't going to win the Gold Medal because Jesse Owens was the best track performer in the world at the time.

Mack Robinson

Jackie followed Mack to Pasadena City, and moved on to the University of California at Los Angeles. His best sport was football, and was one of the best running backs on the West Coast. His next-best sport was basketball, although this was before John Wooden arrived at UCLA and they started winning all those National Championships. Baseball was only his 3rd-best sport. He also played tennis there -- a rarity for black people at the time -- and became the first 4-sport letterman in UCLA history.

He did not graduate from UCLA, leaving with one semester to go, because he had used up all his athletic ability. But the fact that he had played on, and against, integrated teams proved to be very important later on.

It was at UCLA in 1941 that Jackie met Rachel Isum, 3 years younger and a nursing student. They were engaged in 1943, and married in 1946. The fact that Jackie was engaged when Branch Rickey contacted him was also crucial.

Jackie had the idea of becoming a teacher, coach, and/or athletic director at a high school for black kids. But first, like a lot of college athletes, he didn't want to be done with sports. The minor-league Honolulu Bears needed baseball players, and he played there for a while. He got on a ship at Honolulu's Pearl Harbor on December 5, 1941, intending to play football for the minor-league Los Angeles Bulldogs. Two days later, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, putting the kibosh on Jackie's plans.

By the time that Jackie's ship reached California, war had been declared. He enlisted, and while he was at Fort Riley in Kansas (where later baseball star Johnny Damon was born), he and some other black soldiers applied to Officers' Candidate School. They waited for 3 months without hearing if they were accepted.

Heavyweight Champion Joe Louis was transferred to Fort Riley, and these soldiers told him what was happening -- or, rather, what was not happening. Joe made some calls, and the black soldiers were accepted as 2nd Lieutenants.

Lt. Jack Robinson was assigned to the 761st Tank Battalion, an all-black unit known as the Black Panthers, headquartered at Fort Hood, in the segregated State of Texas. There, he became the Rosa Parks of the U.S. Army. Seriously. And this was 11 years before anybody ever heard of Rosa Parks.

On July 6, 1944, Lt. Robinson boarded an Army bus. The driver ordered him to move to the back of the bus. He refused. The driver seemed to let it go, but upon arriving at Fort Hood, he told the military police, and they arrested Jackie. Jackie was court-martialed for insubordination.

This prevented him from being sent overseas with the 761st, meaning he never saw combat. An all-white panel of 9 officers acquitted him of the charges, since the Army is a federal government institution, and federal law supersedes State law, and thus the driver had no authority to order him to the back of the bus.

So even if Jackie had never played professional sports, he still had a story that had to be told. And it was: In 1990, Andre Braugher starred in the TV-movie The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson, with Ruby Dee playing Jackie's mother -- 40 years after she'd played Rachel in The Jackie Robinson Story, in which Jackie played himself.

*

After his acquittal, Jackie was transferred to Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky (also in the South), and served there until being discharged in November 1944. While there, he coached the camp's sports teams, and in so doing met a player from the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League. On the advice of this player (whose name I can't seem to find), he wrote to Monarchs co-owner Thomas Baird, asking for a tryout.

While waiting for word on his tryout, Jackie began what he thought was, and hoped would be, his coaching career, as basketball coach and athletic director at Samuel Huston College (not "Sam Houston"), an all-black school in Austin, Texas, affiliated with the United Methodist Church. It is now known as Huston-Tillotson University, and open to students of all races and affiliations. Among his players was Marques Haynes, who would later star with the Harlem Globetrotters.

The Monarchs did offer Jackie a tryout, and accepted a contract for $400 a month -- about $5,700 in today's money. He played shortstop, and was good enough to appear in the 1945 Negro League All-Star Game. But he didn't like the clowning and gambling that Negro League players liked to do.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a former federal judge who was appointed the first Commissioner of Baseball, was completely opposed to reintegrating the game, over which an unofficial "color bar," "color barrier," "color line," whichever metaphor you want to use, had stood since 1887. It would never have happened in his lifetime. He died on November 25, 1944.

The new Commissioner was Albert Benjamin Chandler, a.k.a. Happy Chandler, a U.S. Senator from Kentucky who had served as that State's Governor (and would again). A Southerner, he was expected by many to keep the color bar.

But the cry of civil rights groups reached him: "If we can stop bullets, why not balls?" Using the language of his place and time, but an attitude far more progressive than that, Chandler said, "If a colored boy can fight on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, he can play in organized baseball." And he stood behind Rickey and Robinson every step of the way. The team owners fired him as Commissioner in 1951, for reasons that had nothing to do with integration.

He was a very conservative politician, a typical Southern Democrat of his time, and later became the first politician known to have said words that have since been identified with Ronald Reagan, "I didn't leave the Democratic Party. It left me." He died in 1991, age 92.

Isadore Muchnick, a Jewish City Councilman in Boston, talked the city's 2 major league teams, the Red Sox and the Braves, into offering black players a tryout that year. Jackie, outfielder Sam Jethroe and 2nd baseman Marvin Williams were offered an alleged chance by the Sox. They went to Fenway Park, and the tryout took place on April 12, 1945 -- a few hours before President Franklin D. Roosevelt died.

Jackie hit the ball all over the yard. Shortstop Johnny Pesky and 2nd baseman Bobby Doerr were still in the service, so there was a need. Muchnick remembered manager Joe Cronin saying, "If I had that guy on the club, we'd be a world-beater." But the players never heard back from the Sox.

Instead of being the first Major League Baseball club to integrate, the Red Sox became the last. In 1979, Cronin -- who I've been led to believe was as much a reason for that as anyone else, especially since their integration didn't happen until 1959 when he left the general manager's post at the club to become President of the American League -- admitted, "It was a great mistake by us. He turned out to be a great player. But no feelings existed about it. We just accepted things as they were."

However, there appears to be no truth to the story that someone shouted from the Fenway stands, "Get that (N-word) off the field!" No doubt, that was shouted somewhere, by somebody, at somebody; but not in this case.

It gets worse: Supposedly, in 1950, the Red Sox had an opportunity to sign a speedy outfielder for the Birmingham Black Barons, Willie Mays. They passed on him, too.

Now, think about this: Imagine that the Sox had signed Jackie, and, seeing the experiment work, went after the other black players who ended up on the Dodgers. Imagine the early-to-mid-1950s Boston Red Sox having the following players: Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Joe Black, Willie Mays, and, oh yeah, the white players they had who were pretty good: Ted Williams, Johnny Pesky, Bobby Doerr, Dom DiMaggio, Vern Stephens, Walt Dropo, Mel Parnell, Ellis Kinder. You think a team like that could have given the Yankees of Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto and Whitey Ford a run for their money?

Whether Sox owner Tom Yawkey, who owned a plantation in South Carolina and palled around with racists, was racist himself, or simply allowed everyone to think he was, he blew it, big-time. You'll notice that, when the Sox finally won another Pennant in 1967, black players were a big part of it: Reggie Smith, George Scott, Joe Foy, Jose Tartabull (Danny's father), Jose Santiago, and, in the final season of his playing career, the first black man to play for the Yankees, Elston Howard.

But they still didn't win a World Series until 2004, with a team that was very well-mixed with white, black, Hispanic and Asian players. If the Sox had integrated in 1945, it seems pretty likely that they would have won a World Series in the next 10 years, and we never would have heard of the Curse of the Bambino. "The Curse of Jackie Robinson" sounds more accurate.

Sam Jethroe did, indeed, become the first black player in Boston -- with the Braves, on April 18, 1950. He was named National League Rookie of the Year, and had All-Star quality seasons in 1951 and '52 as well. But he was already 33 when he debuted, and poor eyesight was catching up to him, making him a liability in the outfield. He played his last big-league game for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1954, and remained in the high minors until 1959. He lived in Erie, Pennsylvania, running a bar until dying in 2001, age 83. Marvin Williams, the other man in the tryout, never played in what was then known as "organized ball."

Branch Rickey sent his chief scout, Clyde Sukeforth, to find an appropriate black player, one who was good enough to make the major leagues if there were no barrier, but also one who could rise above everything that would be thrown at him -- not necessarily the best player, but the best man.

While waiting for word on his tryout, Jackie began what he thought was, and hoped would be, his coaching career, as basketball coach and athletic director at Samuel Huston College (not "Sam Houston"), an all-black school in Austin, Texas, affiliated with the United Methodist Church. It is now known as Huston-Tillotson University, and open to students of all races and affiliations. Among his players was Marques Haynes, who would later star with the Harlem Globetrotters.

The Monarchs did offer Jackie a tryout, and accepted a contract for $400 a month -- about $5,700 in today's money. He played shortstop, and was good enough to appear in the 1945 Negro League All-Star Game. But he didn't like the clowning and gambling that Negro League players liked to do.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a former federal judge who was appointed the first Commissioner of Baseball, was completely opposed to reintegrating the game, over which an unofficial "color bar," "color barrier," "color line," whichever metaphor you want to use, had stood since 1887. It would never have happened in his lifetime. He died on November 25, 1944.

The new Commissioner was Albert Benjamin Chandler, a.k.a. Happy Chandler, a U.S. Senator from Kentucky who had served as that State's Governor (and would again). A Southerner, he was expected by many to keep the color bar.

But the cry of civil rights groups reached him: "If we can stop bullets, why not balls?" Using the language of his place and time, but an attitude far more progressive than that, Chandler said, "If a colored boy can fight on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, he can play in organized baseball." And he stood behind Rickey and Robinson every step of the way. The team owners fired him as Commissioner in 1951, for reasons that had nothing to do with integration.

He was a very conservative politician, a typical Southern Democrat of his time, and later became the first politician known to have said words that have since been identified with Ronald Reagan, "I didn't leave the Democratic Party. It left me." He died in 1991, age 92.

Isadore Muchnick, a Jewish City Councilman in Boston, talked the city's 2 major league teams, the Red Sox and the Braves, into offering black players a tryout that year. Jackie, outfielder Sam Jethroe and 2nd baseman Marvin Williams were offered an alleged chance by the Sox. They went to Fenway Park, and the tryout took place on April 12, 1945 -- a few hours before President Franklin D. Roosevelt died.

Jackie hit the ball all over the yard. Shortstop Johnny Pesky and 2nd baseman Bobby Doerr were still in the service, so there was a need. Muchnick remembered manager Joe Cronin saying, "If I had that guy on the club, we'd be a world-beater." But the players never heard back from the Sox.

Instead of being the first Major League Baseball club to integrate, the Red Sox became the last. In 1979, Cronin -- who I've been led to believe was as much a reason for that as anyone else, especially since their integration didn't happen until 1959 when he left the general manager's post at the club to become President of the American League -- admitted, "It was a great mistake by us. He turned out to be a great player. But no feelings existed about it. We just accepted things as they were."

However, there appears to be no truth to the story that someone shouted from the Fenway stands, "Get that (N-word) off the field!" No doubt, that was shouted somewhere, by somebody, at somebody; but not in this case.

It gets worse: Supposedly, in 1950, the Red Sox had an opportunity to sign a speedy outfielder for the Birmingham Black Barons, Willie Mays. They passed on him, too.

Now, think about this: Imagine that the Sox had signed Jackie, and, seeing the experiment work, went after the other black players who ended up on the Dodgers. Imagine the early-to-mid-1950s Boston Red Sox having the following players: Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Joe Black, Willie Mays, and, oh yeah, the white players they had who were pretty good: Ted Williams, Johnny Pesky, Bobby Doerr, Dom DiMaggio, Vern Stephens, Walt Dropo, Mel Parnell, Ellis Kinder. You think a team like that could have given the Yankees of Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto and Whitey Ford a run for their money?

Whether Sox owner Tom Yawkey, who owned a plantation in South Carolina and palled around with racists, was racist himself, or simply allowed everyone to think he was, he blew it, big-time. You'll notice that, when the Sox finally won another Pennant in 1967, black players were a big part of it: Reggie Smith, George Scott, Joe Foy, Jose Tartabull (Danny's father), Jose Santiago, and, in the final season of his playing career, the first black man to play for the Yankees, Elston Howard.

But they still didn't win a World Series until 2004, with a team that was very well-mixed with white, black, Hispanic and Asian players. If the Sox had integrated in 1945, it seems pretty likely that they would have won a World Series in the next 10 years, and we never would have heard of the Curse of the Bambino. "The Curse of Jackie Robinson" sounds more accurate.

Sam Jethroe did, indeed, become the first black player in Boston -- with the Braves, on April 18, 1950. He was named National League Rookie of the Year, and had All-Star quality seasons in 1951 and '52 as well. But he was already 33 when he debuted, and poor eyesight was catching up to him, making him a liability in the outfield. He played his last big-league game for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1954, and remained in the high minors until 1959. He lived in Erie, Pennsylvania, running a bar until dying in 2001, age 83. Marvin Williams, the other man in the tryout, never played in what was then known as "organized ball."

Branch Rickey sent his chief scout, Clyde Sukeforth, to find an appropriate black player, one who was good enough to make the major leagues if there were no barrier, but also one who could rise above everything that would be thrown at him -- not necessarily the best player, but the best man.

Sukeforth found Robinson, and told Rickey that this was the man, in part because he was an educated man, that he did have a wife-in-waiting, and wasn't the type to run around chasing women, that he wasn't a boozer, and that he had already played with, and against, integrated teams.

On August 28, 1945, Jackie came to the Dodgers' offices. As most teams did in those days, they had their offices away from the ballpark, in their case in downtown Brooklyn at 215 Montague Street. (A bank is on the site now, with a plaque commemorating this meeting.) Red Barber said that Rickey, a very pious Methodist, would use no language harsher than, "Judas Priest!" But he made an exception in this meeting, throwing every insult he could think of at Jackie, to show him what he would have to face.

Jackie sat there, silently, getting angrier and angrier. He figured out that this was a far more sincere opportunity than the Red Sox had offered 2 years earlier, and he knew what Rickey was doing. But it really pissed him off. Finally, a seething Jackie asked, "Mr. Rickey, are you looking for a Negro who is afraid to fight back?"

On August 28, 1945, Jackie came to the Dodgers' offices. As most teams did in those days, they had their offices away from the ballpark, in their case in downtown Brooklyn at 215 Montague Street. (A bank is on the site now, with a plaque commemorating this meeting.) Red Barber said that Rickey, a very pious Methodist, would use no language harsher than, "Judas Priest!" But he made an exception in this meeting, throwing every insult he could think of at Jackie, to show him what he would have to face.

Jackie sat there, silently, getting angrier and angrier. He figured out that this was a far more sincere opportunity than the Red Sox had offered 2 years earlier, and he knew what Rickey was doing. But it really pissed him off. Finally, a seething Jackie asked, "Mr. Rickey, are you looking for a Negro who is afraid to fight back?"

Rickey answered, "Robinson, I'm looking for a Negro with guts enough not to fight back." Rickey was sure that fighting back would result in the racist media saying that blacks couldn't be trusted with a place in the major leagues. He was also sure that, if the experiment failed, it would be 20 years before anyone would dare try again. Rickey asked Jackie if he could be the man he needed.

Jackie sat there, thinking about it, without immediately answering. And that was when Rickey knew he had his man: If Jackie had said yes immediately, it would have been too soon. Jackie thought it over, and agreed.

The Rickey-Robinson agreement was that, for the first 3 years, Jackie would take every slight, without answering in word or deed. Jackie later admitted that there were times when he thought to himself, "To hell with Mr. Rickey's grand experiment." But he never did lash out.

Jackie spent the 1946 season with the Dodgers' top farm team, the Montreal Royals of the International League. He made his "professional debut" for them on April 18, 1946, against the Jersey City Giants at Roosevelt Stadium. He went 4-for-5 with a 3-run homer, as the Royals won, 14-1.

The multicultural fans of Montreal adored him, and after one game ran after him, causing one sportswriter to say, "It was, perhaps, the first time a white mob chased a black man with love, rather than lynching, on their minds." The Royals, already team nearly of major league quality before he got there, won the IL Pennant.

Jackie sat there, thinking about it, without immediately answering. And that was when Rickey knew he had his man: If Jackie had said yes immediately, it would have been too soon. Jackie thought it over, and agreed.

Branch Rickey

Jackie spent the 1946 season with the Dodgers' top farm team, the Montreal Royals of the International League. He made his "professional debut" for them on April 18, 1946, against the Jersey City Giants at Roosevelt Stadium. He went 4-for-5 with a 3-run homer, as the Royals won, 14-1.

The multicultural fans of Montreal adored him, and after one game ran after him, causing one sportswriter to say, "It was, perhaps, the first time a white mob chased a black man with love, rather than lynching, on their minds." The Royals, already team nearly of major league quality before he got there, won the IL Pennant.

The Dodgers already had a shortstop, Pee Wee Reese. He was their team Captain. He was also a Southerner, from Louisville, Kentucky. He was still in the U.S. Navy, not yet discharged even though the war was over, when the announcement was made that Jackie had been signed, on October 23, 1945. When told that Jackie was a shortstop, Pee Wee said, "If he's good enough to take my job, he can have it." Without Reese's support, Jackie never would have made it.

Other Southerners on the team tried to stop him anyway. Dixie Walker circulated a petition among the Southern players. Reese refused to sign it. Catcher Bobby Bragan did sign it, but, like Walker, he soon regretted it. Both men were traded before the 1948 season.

When Rickey died in 1965, Bragan, by then a manager, said he had to come to the funeral, "Because Branch Rickey made me a better man." Before his death in 1982, Walker met with Roger Kahn, who covered the Dodgers for the New York Herald-Tribune, and said he started the petition not because of racial animus, but because he was afraid there would be a backlash against his business interests in Alabama. "That's why I started that thing. It was the dumbest thing I ever did in my life. Would you tell everybody that I'm deeply sorry?"

Leo Durocher, a miserable human being for many reasons (including his Mob ties, which would end up getting him suspended for the entire 1947 season), stood up for Jackie. Remembering the treatment he got as a Catholic kid of French-Canadian descent in his native West Springfield, Massachusetts, he told the Southerners on the Dodgers, "You can take that petition and shove it up your asses. He's gonna win us a lot of games, and he's gonna make us a lot of money." (Then again, money always was Leo the Lip's chief motivator. Maybe that's why he supported Jackie.)

Other Southerners on the team tried to stop him anyway. Dixie Walker circulated a petition among the Southern players. Reese refused to sign it. Catcher Bobby Bragan did sign it, but, like Walker, he soon regretted it. Both men were traded before the 1948 season.

When Rickey died in 1965, Bragan, by then a manager, said he had to come to the funeral, "Because Branch Rickey made me a better man." Before his death in 1982, Walker met with Roger Kahn, who covered the Dodgers for the New York Herald-Tribune, and said he started the petition not because of racial animus, but because he was afraid there would be a backlash against his business interests in Alabama. "That's why I started that thing. It was the dumbest thing I ever did in my life. Would you tell everybody that I'm deeply sorry?"

Leo Durocher, a miserable human being for many reasons (including his Mob ties, which would end up getting him suspended for the entire 1947 season), stood up for Jackie. Remembering the treatment he got as a Catholic kid of French-Canadian descent in his native West Springfield, Massachusetts, he told the Southerners on the Dodgers, "You can take that petition and shove it up your asses. He's gonna win us a lot of games, and he's gonna make us a lot of money." (Then again, money always was Leo the Lip's chief motivator. Maybe that's why he supported Jackie.)

*

With Reese at shortstop, and Eddie Stanky at 2nd base, Sukeforth, the Dodgers' interim manager before Burt Shotton was named to lead them through that season, put Jackie at 1st base. On April 15, 1947, the Dodgers opened the season at home at Ebbets Field, against the Boston Braves -- who had not yet signed Sam Jethroe. The attendance was 26,623, about 5,000 short of capacity, and almost certainly had the highest concentration of black fans of any MLB game to that point.

The Dodger lineup was as follows:

The Dodger lineup was as follows:

2B 1 Eddie Stanky

1B 42 Jackie Robinson

CF 7 Pete Reiser

RF 11 Dixie Walker

LF 22 Gene Hermanski

C 10 Bruce Edwards

3B 21 Johnny "Spider" Jorgensen

SS 1 Pee Wee Rese

P 19 Joe Hatten

Jackie batted in the bottom of the 1st inning, and grounded to 3rd. In the bottom of the 3rd, he flew to left. In the bottom of the 5th, he grounded into a short-2nd-1st double play. In the bottom of the 7th, he reached 1st on a throwing error, a mishandled Stanky bunt by Braves pitcher Johnny Sain, and scored on Reiser's subsequent double. He was replaced in the field in the top of the 9th by Howie Schultz.

The Dodgers won, 5-3. Hal Gregg was the winning pitcher, in relief of Hatten. The last living man who played in this game was Marv Rackley, who pinch-ran for Edwards (making way for Bragan behind the plate). He was also making his major league debut, remained in the majors until 1950, is a native of Seneca, South Carolina, and lived until April 24, 2018, age 96.

The Dodgers won, 5-3. Hal Gregg was the winning pitcher, in relief of Hatten. The last living man who played in this game was Marv Rackley, who pinch-ran for Edwards (making way for Bragan behind the plate). He was also making his major league debut, remained in the majors until 1950, is a native of Seneca, South Carolina, and lived until April 24, 2018, age 96.

Two days after Jackie's debut, another future Hall-of-Famer would make his debut for the Dodgers: A center fielder from Compton, California. That's right: Edwin Donald "Duke" Snider was straight outta Compton.

Hank Greenberg was the one major league player who had a clue as to what Jackie was going through. As the first Jewish player to have lasted in the game, he faced taunts and threats due to his religion, but excelled anyway. In 1947, despite wanting to retire due to a bad back, he accepted a contract from the Pittsburgh Pirates that made him baseball's first $100,000 a year player.

On May 17, 1947, at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, Hank tried to beat a throw to 1st base and ran into Jackie. Not intending any harm, he asked him if he was hurt. Told he wasn't, Hank said to Jackie, "Stick in there. You're doing fine. Keep your chin up." Jackie would later cite Hank's encouragement as a tremendous help.

But most of baseball's current stars stayed out of it. While he would later speak very well of Jackie, Ted Williams did not publicly encourage him in 1947. Joe DiMaggio appears to have said nothing. Nor was there any public word from Stan Musial, whose Cardinals, playing in the semi-Southern city of St. Louis, threatened to go on strike rather than play an integrated team. (More on that in a moment.) Bob Feller, the top pitcher of the time, said he didn't think Robinson was big-league material. Feller would later call saying that the biggest regret of his life.

The worst racial abuse Jackie got came from the Philadelphia Phillies and their manager, Nashville-born Ben Chapman, who'd been an All-Star left fielder for the Yankees in the early 1930s. "Bench jockeying" is one thing, but the kind of venom the Phillies, led by Chapman, spewed at Jackie from the visitors' dugout at Ebbets Field was deeply noxious. Even the Southerners on the Dodgers thought it went too far, and the team as a whole rallied around Jackie.

National League President Ford Frick, who would end up succeeding Chandler as Commissioner, stepped in, and ordered Chapman to pose with Robinson shaking hands for photographs when the Dodgers made their first trip of the season to Philadelphia. He wouldn't do it. So a compromise was reached, with each of them holding one end of a bat. Jackie managed to force a smile for the camera. Chapman could not, and the rage can be seen in his face.

He was fired about a year later, not for his racism, but because the Phillies simply weren't winning. Eddie Sawyer was hired, and he led the "Whiz Kids" of Robin Roberts, Richie Ashburn and Del Ennis to the 1950 NL Pennant -- the last NL Pennant won by an all-white team.

In 1953, the Yankees would beat the Dodgers to win the last World Series, and the last Pennant in either league, by an all-white team. They integrated in 1955; the Phillies, not until 1957.

Frick had already had to step in when the Cardinals threatened to strike. Wendell Smith, writing in the Baltimore Afro-American, in an article published on May 17, 1947, said that the strike was scheduled for May 6, the start of the first meeting of the season between the two teams, who had faced each other in a best-2-out-of-3 Playoff the year before, the Cardinals winning, and had traded Pennants in tight races in the last 2 years before the war started taking most of the big-leaguers, the Dodgers winning in 1941 and the Cards in '42.

So there was already nastiness between the teams. Frick told the Cards that they would be banned from baseball for life if they went through with their threat, and he even upped the ante:

On May 17, 1947, at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, Hank tried to beat a throw to 1st base and ran into Jackie. Not intending any harm, he asked him if he was hurt. Told he wasn't, Hank said to Jackie, "Stick in there. You're doing fine. Keep your chin up." Jackie would later cite Hank's encouragement as a tremendous help.

But most of baseball's current stars stayed out of it. While he would later speak very well of Jackie, Ted Williams did not publicly encourage him in 1947. Joe DiMaggio appears to have said nothing. Nor was there any public word from Stan Musial, whose Cardinals, playing in the semi-Southern city of St. Louis, threatened to go on strike rather than play an integrated team. (More on that in a moment.) Bob Feller, the top pitcher of the time, said he didn't think Robinson was big-league material. Feller would later call saying that the biggest regret of his life.

The worst racial abuse Jackie got came from the Philadelphia Phillies and their manager, Nashville-born Ben Chapman, who'd been an All-Star left fielder for the Yankees in the early 1930s. "Bench jockeying" is one thing, but the kind of venom the Phillies, led by Chapman, spewed at Jackie from the visitors' dugout at Ebbets Field was deeply noxious. Even the Southerners on the Dodgers thought it went too far, and the team as a whole rallied around Jackie.

National League President Ford Frick, who would end up succeeding Chandler as Commissioner, stepped in, and ordered Chapman to pose with Robinson shaking hands for photographs when the Dodgers made their first trip of the season to Philadelphia. He wouldn't do it. So a compromise was reached, with each of them holding one end of a bat. Jackie managed to force a smile for the camera. Chapman could not, and the rage can be seen in his face.

He was fired about a year later, not for his racism, but because the Phillies simply weren't winning. Eddie Sawyer was hired, and he led the "Whiz Kids" of Robin Roberts, Richie Ashburn and Del Ennis to the 1950 NL Pennant -- the last NL Pennant won by an all-white team.

In 1953, the Yankees would beat the Dodgers to win the last World Series, and the last Pennant in either league, by an all-white team. They integrated in 1955; the Phillies, not until 1957.

Frick had already had to step in when the Cardinals threatened to strike. Wendell Smith, writing in the Baltimore Afro-American, in an article published on May 17, 1947, said that the strike was scheduled for May 6, the start of the first meeting of the season between the two teams, who had faced each other in a best-2-out-of-3 Playoff the year before, the Cardinals winning, and had traded Pennants in tight races in the last 2 years before the war started taking most of the big-leaguers, the Dodgers winning in 1941 and the Cards in '42.

So there was already nastiness between the teams. Frick told the Cards that they would be banned from baseball for life if they went through with their threat, and he even upped the ante:

You will find that the friends you think you have in the press box will not support you, that you will be outcasts. I do not care if half the league strikes. Those who do it will encounter quick retribution. All will be suspended, and I don't care if it wrecks the National League for five years.

This is the United States of America, and one citizen has as much right to play as another. The National League will go down the line with Robinson, whatever the consequences. You will find if you go through with your intention that you have been guilty of complete madness.

The strike did not happen, and the Cards ended up finishing a close 2nd to the Dodgers. The Cards would do so again in 1949, and then their 1940s dynasty got old. They didn't integrate until 1954, with Tom Alston. Not until they had a much bigger black representation, with Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, Bill White and Curt Flood leading the way, did they win another Pennant, in 1964.

In addition to Robinson with the Dodgers, Jethroe with the Braves, Alston with the Cardinals and Howard with the Yankees in 1955, the following were the first black players on each team:

* Cleveland Indians, Larry Doby, 1947, the first black player in the AL.

* St. Louis Browns (who became the Baltimore Orioles in 1954: Hank Thompson, later in '47.

* New York Giants: The aforementioned Hank Thompson, and Monte Irvin, debuting in the same game in 1949.

* Chicago White Sox: Minnie Minoso, 1951, becoming the game's first black Hispanic.

* Philadelphia Athletics: Bob Trice, 1953.

* Chicago Cubs: Ernie Banks, also 1953.

* Pittsburgh Pirates: Curt Roberts, 1954.

* Cincinnati Reds: Nino Escalera and Chuck Harmon, debuting in the same game in '54.

* Washington Senators: Carlos Paula, 1954.

* Philadelphia Phillies: John Kennedy, 1957.

* Detroit Tigers: Ozzie Virgil Sr., 1958.

* And the Boston Red Sox, finally getting with the program with Elijah "Pumpsie" Green, on July 21, 1959.

Trains nicknamed "Jackie Robinson Specials" were hired by black civic groups to take them from Southern cities to the semi-Southern city of Cincinnati when the Dodgers played the Reds at Crosley Field.

So much has been made of Jackie Robinson the pioneer that Jackie Robinson the player often gets forgotten. In that first season, he struggled at the plate at first, but caught fire, getting his batting average up to .316 before finishing at .297, with 12 homers, 48 RBIs, and 29 stolen bases. The Rookie of the Year award was given out for the first time, and Jackie won it.

In 1949, having fulfilled his 3-year promise to Rickey, Jackie began arguing umpires' calls, and asserting himself in other ways. He had his best season, winning the NL batting title with a .342 average, hitting 16 homers, and topping 100 RBIs for the only time in his career, with 124. He also stole a career-high 37 bases.

Jackie Robinson changed how the game of baseball was played, not just by whom. Red Barber said Jackie was the only player he'd ever seen whose very threat to steal caused a pitcher to walk the bases loaded, and then, with Jackie threatening to steal home plate, walk the next batter to force home a run.

His kind of baserunning hadn't really been seen outside the Negro Leagues before. For the first time since Ruth turned the home run from a rarity to a common occurrence, baserunning was a weapon. My grandmother, a Dodger fan growing up in South Jamaica, Queens, remembered him dancing off the bases, and she never saw another player do so much to drive pitchers crazy.

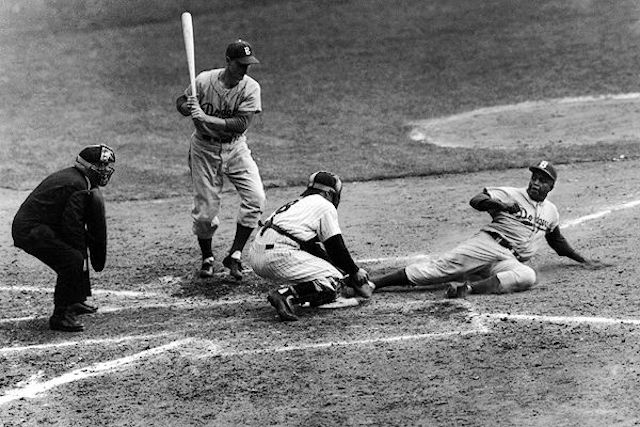

Jackie stole home 19 times in regular-season games, plus 1 more time in Game 1 of the 1955 World Series, and Yogi Berra went to his grave still saying that Jackie was out. The film seems to back Yogi up, but it doesn't matter now, does it?

In his autobiography, I Never Had It Made, published right after his death, Jackie said the highlight of his career was standing on the foul line at Yankee Stadium for Game 1 of the World Series, on September 30, 1947. He and his teammates had made it, together. They had faced every obstacle, and now they were playing for the championship of the world. The Dodgers lost that Series in 7 games, and Jackie batted .259 (7-for-27) with 3 RBIs.

Walter O'Malley, a part-owner of the Dodgers who bought Rickey out after the 1950 season, hated Rickey and anything to do with Rickey -- including Jackie. With Stanky having been traded after the 1947 season, Jackie had settled at 2nd base. But in 1953 he was being put at 3rd base and the outfield more often. Jim Gilliam, another black player, came up in '53, and began taking Jackie's place in the lineup.

In 1954, O'Malley hired Walter Alston as manager, and while Alston's commitment to treating his players fairly regardless of race has never been seriously questioned, he seemed to be under O'Malley's orders to let Jackie know that his time was running out. Although the Dodgers finally won the World Series in 1955, Alston did not play Jackie in the deciding Game 7 on October 4.

In all fairness, Jackie had put on some weight, and his batting average dropped from .311 (which turned out to be his career average) in 1954 to .256 in '55. He still managed to steal home plate on Whitey Ford and Yogi Berra in Game 1 of the 1955 World Series, although Yogi insisted to the end that Jackie was out, and the Yankees won the game anyway -- but not the Series.

So much has been made of Jackie Robinson the pioneer that Jackie Robinson the player often gets forgotten. In that first season, he struggled at the plate at first, but caught fire, getting his batting average up to .316 before finishing at .297, with 12 homers, 48 RBIs, and 29 stolen bases. The Rookie of the Year award was given out for the first time, and Jackie won it.

In 1949, having fulfilled his 3-year promise to Rickey, Jackie began arguing umpires' calls, and asserting himself in other ways. He had his best season, winning the NL batting title with a .342 average, hitting 16 homers, and topping 100 RBIs for the only time in his career, with 124. He also stole a career-high 37 bases.

Jackie Robinson changed how the game of baseball was played, not just by whom. Red Barber said Jackie was the only player he'd ever seen whose very threat to steal caused a pitcher to walk the bases loaded, and then, with Jackie threatening to steal home plate, walk the next batter to force home a run.

His kind of baserunning hadn't really been seen outside the Negro Leagues before. For the first time since Ruth turned the home run from a rarity to a common occurrence, baserunning was a weapon. My grandmother, a Dodger fan growing up in South Jamaica, Queens, remembered him dancing off the bases, and she never saw another player do so much to drive pitchers crazy.

Jackie stole home 19 times in regular-season games, plus 1 more time in Game 1 of the 1955 World Series, and Yogi Berra went to his grave still saying that Jackie was out. The film seems to back Yogi up, but it doesn't matter now, does it?

In his autobiography, I Never Had It Made, published right after his death, Jackie said the highlight of his career was standing on the foul line at Yankee Stadium for Game 1 of the World Series, on September 30, 1947. He and his teammates had made it, together. They had faced every obstacle, and now they were playing for the championship of the world. The Dodgers lost that Series in 7 games, and Jackie batted .259 (7-for-27) with 3 RBIs.

Walter O'Malley, a part-owner of the Dodgers who bought Rickey out after the 1950 season, hated Rickey and anything to do with Rickey -- including Jackie. With Stanky having been traded after the 1947 season, Jackie had settled at 2nd base. But in 1953 he was being put at 3rd base and the outfield more often. Jim Gilliam, another black player, came up in '53, and began taking Jackie's place in the lineup.

In 1954, O'Malley hired Walter Alston as manager, and while Alston's commitment to treating his players fairly regardless of race has never been seriously questioned, he seemed to be under O'Malley's orders to let Jackie know that his time was running out. Although the Dodgers finally won the World Series in 1955, Alston did not play Jackie in the deciding Game 7 on October 4.

In all fairness, Jackie had put on some weight, and his batting average dropped from .311 (which turned out to be his career average) in 1954 to .256 in '55. He still managed to steal home plate on Whitey Ford and Yogi Berra in Game 1 of the 1955 World Series, although Yogi insisted to the end that Jackie was out, and the Yankees won the game anyway -- but not the Series.

What's your call?

His last hurrah was driving in the winning run in the bottom of the 10th inning in Game 6 of the 1956 World Series, but in Game 7, on October 10, 1956, the Yankees shelled the Dodgers, 9-0. Jackie's last at-bat was the last out of the game, a strikeout, but Yogi dropped the 3rd strike. Remembering the Mickey Owen play from the 1941 Series between the teams, Jackie took off for 1st; but Yogi remembered it as well, got the ball, and threw him out.

On December 13, O'Malley traded Jackie to the arch-rival Giants for Dick Littlefield (you don't need to know anything else about him) and $30,000. Jackie's response to this F.U. from O'Malley was to F.U. him right back: He retired rather than report to the enemy. He had played 10 seasons, and was about to turn 38.

Jackie was hired as Chairman by the black-owned Freedom National Bank, and also worked as an executive for the Chock Full o' Nuts coffee and restaurant company. Like Rickey, he was a Republican of the Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt variety, and saw the GOP ideal of self-reliance and getting involved in business as a way up for black people.

When Nelson Rockefeller ran for Governor of New York in 1958, he hired Jackie as an advisor, and Jackie's efforts to help Rocky reach out to the black communities of the Empire State were a factor in the Republican Rocky beating the Democratic incumbent, Averell Harriman. Jackie attended the March On Washington in 1963, and in 1965 became the first black broadcaster in baseball, on ABC's telecasts.

But politics would disillusion Jackie. He worked to help get Rockefeller the Republican nomination for President in 1964, but it went instead to Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, who had voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, on constitutional rather than racial grounds.

On December 13, O'Malley traded Jackie to the arch-rival Giants for Dick Littlefield (you don't need to know anything else about him) and $30,000. Jackie's response to this F.U. from O'Malley was to F.U. him right back: He retired rather than report to the enemy. He had played 10 seasons, and was about to turn 38.

Jackie was hired as Chairman by the black-owned Freedom National Bank, and also worked as an executive for the Chock Full o' Nuts coffee and restaurant company. Like Rickey, he was a Republican of the Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt variety, and saw the GOP ideal of self-reliance and getting involved in business as a way up for black people.

When Nelson Rockefeller ran for Governor of New York in 1958, he hired Jackie as an advisor, and Jackie's efforts to help Rocky reach out to the black communities of the Empire State were a factor in the Republican Rocky beating the Democratic incumbent, Averell Harriman. Jackie attended the March On Washington in 1963, and in 1965 became the first black broadcaster in baseball, on ABC's telecasts.

But politics would disillusion Jackie. He worked to help get Rockefeller the Republican nomination for President in 1964, but it went instead to Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, who had voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, on constitutional rather than racial grounds.

Rockefeller was nearly booed off the stage at the Republican Convention, which Jackie attended. Roger Kahn was covering that convention for The Saturday Evening Post, and Jackie told him, "It would make everything I worked for meaningless if baseball were integrated but our political parties were segregated."

Although Jackie had voted for Richard Nixon in 1960, as Nixon then seemed to him to be more interested in the cause of civil rights than John F. Kennedy, who he didn't think showed him enough respect, he voted for Lyndon Johnson over Goldwater in '64, and the very pro-civil rights Hubert Humphrey over Nixon, who had adopted a "Southern Strategy," in '68.

Jackie had already taken some heat for testifying before Congress in 1949, to counter statements made by black athlete turned actor turned social activist Paul Robeson. Jackie would later regret this. He also refused to stand up for Ali when Ali fought the draft during the Vietnam War; a surviving film clip shows him twice using Ali's birth name, "Cassius." He thought Ali was doing the cause of civil rights more harm than good, and he did not live long enough to see Ali's vindication.

Jackie may have been a Lincoln-style, TR-style, Eisenhower-style Republican, and perhaps he could have supported Ronald Reagan and his anti-welfare crusade in the 1980s; but there is no place for someone like him in the Trump-dominated GOP of 2019, where neo-Confederates and neo-Nazis are considered "very fine people" by the man in the White House.

On June 4, 1972, with Jackie's health failing, diabetes already claiming most of his eyesight, giving him heart trouble, and his doctors telling him he might soon lose a leg, his Number 42 was retired by the Dodgers in a ceremony at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles -- ironically, his hometown, even though he never played for them there. Roy Campanella's 39 and Sandy Koufax' 32 were also retired that day.

Jackie became the first black player in the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, with Campy becoming the second in 1969. In 1999, he was voted by fans onto the Major League Baseball All-Century Team; Joe Morgan, another 2nd baseman nominated for it and by then a broadcaster, said that if he were named to the team, and Jackie wasn't, he would give up his place for Jackie. (It was a legitimate possibility, as he finished 3rd in the voting behind Jackie and Rogers Hornsby. Certainly, Morgan is the greatest 2nd baseman of my lifetime, although he was a terrible broadcaster.)

Jackie was invited to throw out the ceremonial first ball before Game 2 of the 1972 World Series in commemoration of the 25th Anniversary of his debut. With some of his Dodger teammates on hand, and Red Barber introducing him, he spoke in public for the last time: "I'm extremely pleased to be here, but I must admit, I'm going to be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third base coaching line one day, and see a black face managing in baseball."

Putting aside the already-obsolete notion of a team's manager also coaching at 3rd base, the first black manager came 2 years later, on October 3, 1974, when Cleveland Indians owner Ted Bonda, deciding that he had the right man for the job already playing for him, hired Frank Robinson. In 1981, Frank would become the first black manager in the NL, hired by the San Francisco Giants.

Ironically, by that point, most black high school athletes in America were moving on to football or basketball rather than baseball. By the 1990s, black Hispanics had begun to dominate the game, and the number of American-born black men on big-league rosters has radically shrunk -- not by management's choice, but by their own. This is not something Jackie would ever have had in mind.

Jackie didn't live to see Frank's hiring: He suffered a heart attack on October 24, 1972, at the family home in Stamford, Connecticut. He was survived by Rachel, their daughter Sharon, and their son David. Son Jackie Jr. died in a car crash in 1971.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson presided over his funeral, and among his pallbearers were Pee Wee Reese, Don Newcombe, and Bill Russell -- the basketball legend, not the man of the same name who was then the shortstop for the Dodgers. He was buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn, through which the Interborough Parkway cut. In 1997, it was renamed the Jackie Robinson Parkway.

Today, Rachel, founder of the Jackie Robinson Foundation, is 97 years old, and lives on a farm outside Stamford. She had waited until the right film was set up before she gave her permission. She said she was pleased with how the film 42, released in 2013, came out. Jackie was played by Chadwick Boseman, Rachel by Nicole Behaire, and Branch Rickey by Harrison Ford.

Although Jackie had voted for Richard Nixon in 1960, as Nixon then seemed to him to be more interested in the cause of civil rights than John F. Kennedy, who he didn't think showed him enough respect, he voted for Lyndon Johnson over Goldwater in '64, and the very pro-civil rights Hubert Humphrey over Nixon, who had adopted a "Southern Strategy," in '68.

Jackie had already taken some heat for testifying before Congress in 1949, to counter statements made by black athlete turned actor turned social activist Paul Robeson. Jackie would later regret this. He also refused to stand up for Ali when Ali fought the draft during the Vietnam War; a surviving film clip shows him twice using Ali's birth name, "Cassius." He thought Ali was doing the cause of civil rights more harm than good, and he did not live long enough to see Ali's vindication.

Jackie may have been a Lincoln-style, TR-style, Eisenhower-style Republican, and perhaps he could have supported Ronald Reagan and his anti-welfare crusade in the 1980s; but there is no place for someone like him in the Trump-dominated GOP of 2019, where neo-Confederates and neo-Nazis are considered "very fine people" by the man in the White House.

On June 4, 1972, with Jackie's health failing, diabetes already claiming most of his eyesight, giving him heart trouble, and his doctors telling him he might soon lose a leg, his Number 42 was retired by the Dodgers in a ceremony at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles -- ironically, his hometown, even though he never played for them there. Roy Campanella's 39 and Sandy Koufax' 32 were also retired that day.

Jackie became the first black player in the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, with Campy becoming the second in 1969. In 1999, he was voted by fans onto the Major League Baseball All-Century Team; Joe Morgan, another 2nd baseman nominated for it and by then a broadcaster, said that if he were named to the team, and Jackie wasn't, he would give up his place for Jackie. (It was a legitimate possibility, as he finished 3rd in the voting behind Jackie and Rogers Hornsby. Certainly, Morgan is the greatest 2nd baseman of my lifetime, although he was a terrible broadcaster.)

Jackie was invited to throw out the ceremonial first ball before Game 2 of the 1972 World Series in commemoration of the 25th Anniversary of his debut. With some of his Dodger teammates on hand, and Red Barber introducing him, he spoke in public for the last time: "I'm extremely pleased to be here, but I must admit, I'm going to be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third base coaching line one day, and see a black face managing in baseball."

That speech. The best thing about this photo

is that Jackie is half-blocking out Commissioner Bowie Kuhn.

Ironically, by that point, most black high school athletes in America were moving on to football or basketball rather than baseball. By the 1990s, black Hispanics had begun to dominate the game, and the number of American-born black men on big-league rosters has radically shrunk -- not by management's choice, but by their own. This is not something Jackie would ever have had in mind.

Jackie didn't live to see Frank's hiring: He suffered a heart attack on October 24, 1972, at the family home in Stamford, Connecticut. He was survived by Rachel, their daughter Sharon, and their son David. Son Jackie Jr. died in a car crash in 1971.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson presided over his funeral, and among his pallbearers were Pee Wee Reese, Don Newcombe, and Bill Russell -- the basketball legend, not the man of the same name who was then the shortstop for the Dodgers. He was buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn, through which the Interborough Parkway cut. In 1997, it was renamed the Jackie Robinson Parkway.

Today, Rachel, founder of the Jackie Robinson Foundation, is 97 years old, and lives on a farm outside Stamford. She had waited until the right film was set up before she gave her permission. She said she was pleased with how the film 42, released in 2013, came out. Jackie was played by Chadwick Boseman, Rachel by Nicole Behaire, and Branch Rickey by Harrison Ford.

Sharon is 69, a teacher, and a former midwife. David is 66, and, ironically, runs a plantation in Africa, growing coffee in Tanzania, but also works to fight poverty there.

On April 15, 1997, a ceremony honoring the 50th Anniversary of Jackie's debut was held at Shea Stadium in New York, during a game between the Mets and the Los Angeles edition of the Dodgers. Reese, then dying of cancer, could not attend. But several of his teammates did, including Newcombe, Snider, and Koufax -- who wore a Mets cap in honor of his classmate at Brooklyn's Lafayette High School, Met owner Fred Wilpon. Rachel, Sharon and David attended, as did President Bill Clinton.

So did I: I won 2 tickets in a radio contest, and, knowing I'd never be able to live with myself if I didn't, took my Grandma, and together we were part of a sellout crowd of 54,047 paying tribute to the man who was her all-time hero in life, not just in sports.

Commissioner Bud Selig announced an unprecedented honor: Number 42 would be retired through all of baseball, the major leagues and the minors alike. All players still wearing the number would get to keep it, including the Mets' Butch Huskey, the Red Sox' Mo Vaughn, and the man who, in 2013, left the field for the last time as the last player who will ever wear it as his own number, Mariano Rivera of the Yankees. (Each year, on April 15, starting on the 60th Anniversary in 2007, every player wears Number 42.) Not that it matters, but the Mets beat the Dodgers, 5-0. The home plate umpire was a black man, Eric Gregg.

On the way out of Shea that night, April 15, 1997, Grandma and I left by Gate C, the home plate entrance, where fans waited for autographs from the players. As it turned out, the Robinson family was right behind us. We got to meet Rachel, and it was a thrill that Grandma carried with her for the rest of her life.

The Mets have done more to honor Jackie's legacy than even the Dodgers. Their new home, Citi Field, was designed to look like Ebbets Field, and like Ebbets Field has a rotunda at the home plate entrance. The rotunda is named for Jackie, and is the baseball equivalent of a "Presidential Library."

But in 2017, on the 70th Anniversary of Jackie's debut, the Dodgers placed a statue of him outside Dodger Stadium, behind the left field pavilion -- in the direction of his hometown of Pasadena.

Although Grandma went to a few Lakewood BlueClaws games when that team was established, she never went to another major league game. Her last experience at a Major League Baseball game was her favorite. And, through a stroke of luck with a radio station, I was able to bring it to her.

Jackie Robinson made my Grandma happy that night, 25 years after his death. Even 47 years after his death, and 100 years after his birth, he is still making an impact. And there's not many people about whom we can say that.

Inscribed on his tombstone is a quote of his: "A life is not important, except in the impact it has on other lives."

No comments:

Post a Comment