Willie Lee McCovey was born on January 10, 1938 in Mobile, Alabama. He is the greatest lefthanded hitter ever to come from that city. But not the greatest hitter overall: That would be Hank Aaron. Aaron is the reason McCovey wore Number 44 throughout his career. Aaron is also the reason Reggie Jackson wore 44 starting with his arrival on the Yankees in 1977 -- after his original choices, 9 which he'd worn in Oakland and Baltimore, and 42 in memory of Jackie Robinson, were unavailable.

In what turned out to be one of his last interviews, he talked about the practice, common at the time, of radio announcers reading baseball plays off a telegraph: "At night, we'd gather around the radio to listen to a guy who recreated the play-by-play of Major League Baseball games by reading the ticker. With sound effects, he made it seem real.

"My friends and I played sports in the streets or empty fields. We played softball in a large local playground. Jesse Thomas was the director. I pitched, and was a better pitcher than a first baseman. But I could hit the ball hard."

McCovey dropped out of school at age 12, and went to work full-time. On March 12, 1955, shortly after he turned 18, the New York Giants, among the earliest teams to desegregate, signed him as a free agent. They kept him in the South for most of his minor-league days, with the Sandersville Giants in the Class D Georgia State League in 1955, the Danville Leafs of Virginia in the Class B Carolina League in 1956, and the Dallas Eagles in the Class AA Texas League in 1957. At every step, he proved what a powerful hitter he was, including helping the Eagles win the Pennant.

There was a problem, though: Willie was a 1st baseman, and the Giants already had a great-hitting 1st baseman coming through the ranks: Orlando Cepeda. He reached the big club in 1958, and won the National League Rookie of the Year. Willie was stuck on the Phoenix Giants of the Class AAA Pacific Coast League in 1958 and 1959, until, finally, they had little choice but to call him up.

He made his major league debut on July 30, 1959, at Seals Stadium in San Francisco, the home of the city's former PCL team that the Giants were using as a temporary home until Candlestick Park could open the next year. Batting 3rd and playing 1st base, while Cepeda played 3rd base, Willie had one of the best debuts in MLB history, going 4-for-4, all off fellow future Hall-of-Famer Robin Roberts: Singling to right in the 1st inning, hitting a leadoff triple to center in the 4th, singling Willie Mays home in the 5th, and tripling Mays home in the 7th. Mike McCormick went the distance for the Giants, and they beat the Philadelphia Phillies 7-2.

McCovey finished the 1959 season with a .354 batting average -- but not enough plate appearances to qualify for the NL batting title -- 13 home runs and 38 RBIs. That was in 2 months of play. Nevertheless, he won the NL Rookie of the Year award in a unanimous vote.

*

He kept hitting, and Giants management kept wondering what to do with these 2 gems, McCovey and Cepeda, who both wanted to play 1st base. There was no designated hitter in those days, and it was the NL, anyway. McCovey was put in left field. In 1962, he helped the Giants win their 1st Pennant since the move to San Francisco.

McCovey showing why he was called "Stretch," reaching for a high

pickoff throw at Yankee Stadium during the 1962 World Series.

Mickey Mantle got back to 1st safely anyway.

That's 2 guys, 1,057 career home runs.

They played the Yankees in the World Series, and it went to Game 7 at Candlestick. Tony Kubek, the Yankee shortstop, who missed much of the season due to military service, grounded into a double play in the 5th inning, but a run scored on the play. The score remained Yankees 1, Giants 0 in the bottom of the 9th. With 2 outs and Matty Alou on 1st‚ Mays ripped a double to right off Ralph Terry‚ but great fielding by Roger Maris kept Alou from scoring.

The Yankees now had a choice to make: Have the righthanded Terry, who gave up Bill Mazeroski's Series-winning homer in Game 7 in 1960, pitch to the next batter, the dangerous lefthander McCovey; or walk him to load the bases and set up the Series-clinching out at any base, and pitch to the equally dangerous but righthanded Orlando Cepeda.

Bobby Richardson, the Yankees' 2nd baseman, later said in an interview, "Really, not much of a choice." It was like choosing between the guillotine and the hangman's noose. Oddly, despite all the talk about whether to pitch to McCovey or Cepeda, removing the tiring righthanded Terry for a relief pitcher, possibly a lefthander to pitch to the lefthanded McCovey, seems never to have been discussed.

They decided to pitch to McCovey. He hit a screaming liner toward right field‚ but Richardson took one step to his left and snared it. Ballgame over, and the Yankees won -- barely.

Peanuts cartoonist Charles Schulz, a Giants fan living in nearby Santa Rosa, soon drew a cartoon having Charlie Brown yell to the heavens about it. A month later, he drew another.

In 1986, when he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, he was asked how he'd like to be remembered, he said, "I'd like to be remembered as the guy who hit the ball over Bobby Richardson's head in the seventh game." As recently as 2014, he said, "I still think about it all the time. I still think, 'If I could have hit it a little more... "

That's not fair. It's nearly impossible to hit a ball harder than McCovey did at that moment. He did his job as well as anyone could have legitimately asked, and the Giants took the Series to the last out of the last game. They just got beat by a team that was a little bit better -- or, maybe, given that the line drive didn't tear Richardson's glove off, maybe a little luckier.

In 1963, McCovey was named to his 1st All-Star Game, and led the NL with 44 home runs, despite the windy conditions at Candlestick. The Giants would have near-misses in the 1964, '65 and '66 seasons, finishing a combined 6 1/2 games out of 1st place in those 3 seasons.

A knee injury limited Cepeda to just 33 games in '65, making McCovey the regular 1st baseman. Trading Cepeda to the St. Louis Cardinals early in '66 ensured that the job was McCovey's long-term. (In spite of wanting to play the same position, there was never any bad blood between Cepeda and McCovey.)

On the one hand, this was a bad trade: The Giants got Ray Sadecki, a lefthanded pitcher who'd helped the Cards win the 1964 World Series, but he got hit hard with the Giants; while Cepeda's knee got better, and he helped the Cards win the Pennant in 1967 (and the World Series, too) and '68.

But McCovey became the best 1st baseman in baseball: At 6-foot-4 and 200 pounds, he was able to reach up to get high throws, and stretch out to get low ones. "Stretch" became his nickname. When McDonald's introduced the Big Mac burger in 1968, Willie also became known as "Big Mac."

Mays said, "He could hit a ball farther than anyone I ever played with. You could talk all day about balls he hit." On September 16, 1966, he hit what was probably the longest home run in Candlestick Park history, about 500 feet.

In 1968, he led the NL with 36 homers and 105 RBIs. In 1969, he led in both categories again, reaching career highs with 45 homers and 126 RBIs. In spite of the Mets' "Miracle" season, McCovey edged Tom Seaver for the NL Most Valuable Player award. In 1970, he hit 39 homers, and again had 126 RBIs.

The National League's starting lineup at the 1969 All-Star Game

in Washington. Left to right: Manager Red Schoendienst,

left fielder Matty Alou, shortstop Don Kessinger,

right fielder Hank Aaron, 1st baseman Willie McCovey,

3rd baseman Ron Santo, left fielder Cleon Jones,

catcher Johnny Bench, and 2nd baseman Félix Millán.

Starting pitcher Steve Carlton was warming up in the bullpen.

Hall-of-Famers in bold.

But the Giants' tendency for near-misses continued. In 1969, the 1st season of Divisional Play, they were 3 games short of the NL Western Division title. In 1971, they won the NL West, but lost the NL Championship Series to the Pittsburgh Pirates. And injuries caught up with him. Both of his knees were injured, and he developed arthritis in them.

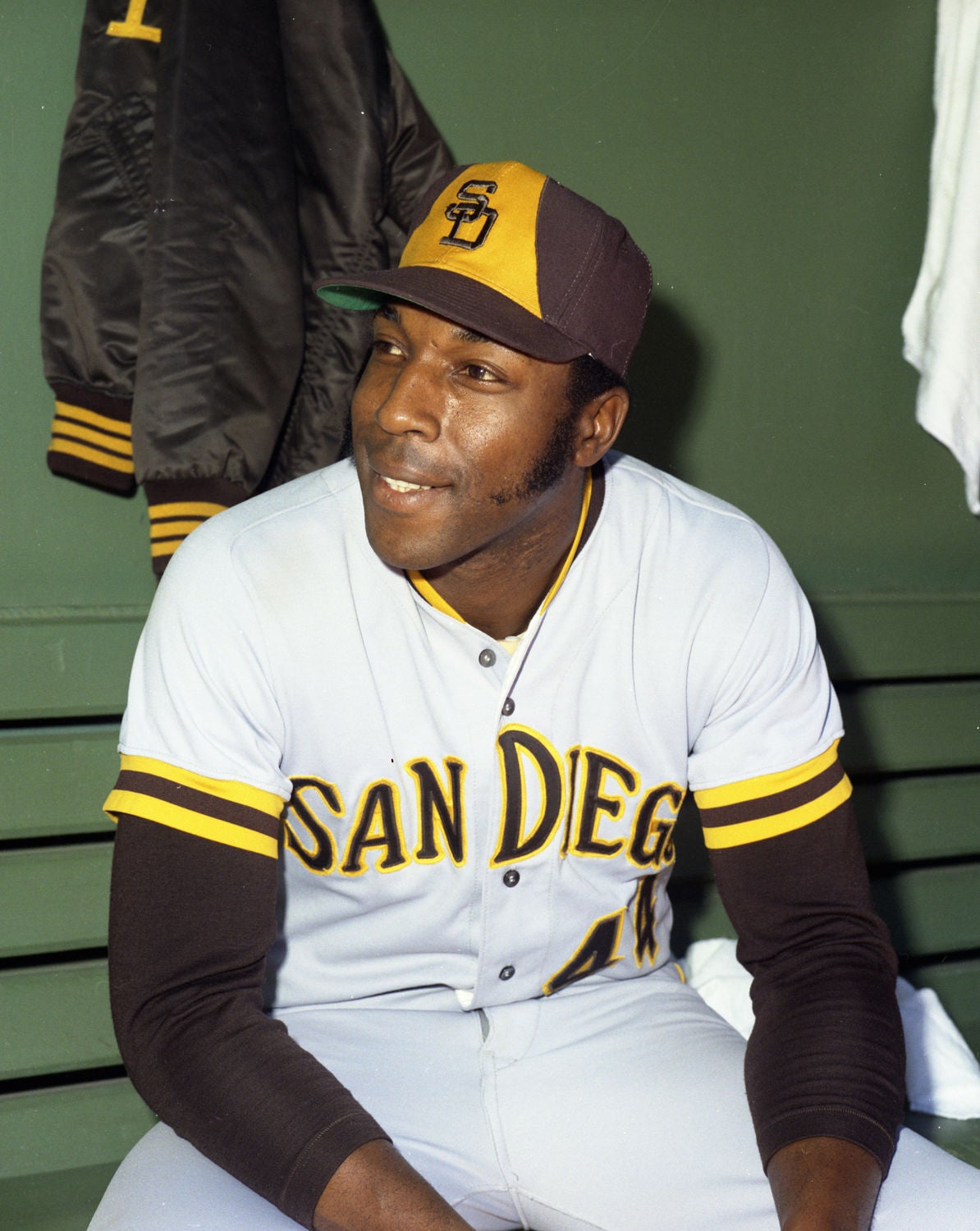

And then came the unthinkable. Or maybe, not so unthinkable, because of the trade of Mays to the Mets a year earlier. But on October 25, 1973, Willie Mac, the most popular player in San Francisco Giants history -- as a newspaper columnist once said, San Francisco was a city where "they cheer Khrushchev and boo Willie Mays" -- was traded to the San Diego Padres, along with Bernie Williams, for pitcher Mike Caldwell.

Brown clothes and sideburns: A classically Seventies combination.

No, not that Bernie Williams. This was an outfielder who never really made it. Caldwell was a 25-year-old lefthander. He pitched well for the Giants in 1974, but was clobbered in '75 and '76, and they traded him away. It took until 1978, with the Milwaukee Brewers, for him to develop the curveball that would make him one of the nastiest pitchers in the American League for a few years, and he finished 137-130 for his career -- but only 22-25 for the Giants.

Willie said, "I'm just 35, and I can still play 3 or 4 more years on the field. I feel in pretty good shape, and stay in good shape."

Willie McCovey, a San Diego Padre? It didn't seem right. He was with them for nearly 3 seasons, until August 30, 1976, when Charlie Finley bought his contract for the Oakland Athletics, hoping that his presence in the lineup could help the A's win the AL West for the 6th straight season, and that Giant fans might cross San Francisco Bay to pay to see their former hero at the Oakland Coliseum. Neither hope was realized: People in the Bay Area liked the A's, but they hated Finley, and didn't want to give them their money.

Santo played for the Chicago White Sox, Sal Maglie

for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the 1990s Yankees

had a few ex-Mets. So this image isn't that strange.

Finley, one of the cheapest baseball team owners of the modern era, basically used Willie as a rental, and didn't try to re-sign him as his contract ran out. The Giants reached out to him, and brought him home. In 1977, at age 39, he batted .280 (his best average in 7 years), hit 28 home runs (his best in 4), and had 86 RBIs (his best in 8). He was named NL Comeback Player of the Year.

Orange and sideburns: An even more classically Seventies combination.

Manager Joe Altobelli, later a coach for the Yankees' 1981 American League Pennant winners and manager of the Baltimore Orioles' 1983 World Champions, said, "We didn't want Willie to embarrass himself. He has done just the opposite. He's had a super Spring, and he's a super person. If I had his body, and I'm 45, I think I'd still be playing, too."

It wasn't quite a last gasp, but it was his last great season. On June 30, 1978, he hit the 500th home run of his career off Jamie Easterly of the Atlanta Braves, at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. He announced his retirement effective with the 1980 All-Star Break, and got proper farewells, both at Candlestick and at the place where he ended up playing his last game, on July 6: The home of the Giants' arch-rivals, Dodger Stadium. After an RBI sacrifice fly in his last at-bat, the Los Angeles fans gave him a nice hand.

He finished with a lifetime batting average of .270, 2,211 hits including 521 home runs, and 1,555 RBIs. Oddly, he only made 6 All-Star Games. At the time he retired, his 521 homers tied him with Ted Williams for 8th on the all-time list. It was the most any lefthanded hitter had hit in National League play, surpassing a previous Giant, from the New York era, Mel Ott. McCovey himself would be surpassed by another Giant, Barry Bonds *. Of McCovey's 521 home runs, 18 were grand slams, which remains a National League record.

*

On September 21, 1980, the Giants retired his Number 44, and instituted the Willie Mac Award, given annually to the Giants' "most inspirational player." The 1st winner was Jack Clark.

In 1986, his 1st year of eligibility, Willie was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. I attended the induction ceremony. The streets of Cooperstown, New York were loaded with Giants fans, many of them wearing the black caps with the orange SF monogram, some of them wearing "Croix de Candlestick" pins.

Incidentally, let me give you some advice: Unless it's someone you have to see, like your childhood idol, don't go to Cooperstown on Induction Weekend. A town with 2,500 or so permanent residents simply isn't equipped to handle 100,000 visitors. It's why the induction ceremony was moved to a new facility outside of town in 1992, with shuttle bus service. Go, but go any other time.

In 1996, he and fellow Hall-of-Famer Duke Snider of the Brooklyn Dodgers pled guilty to federal tax fraud charges, for failing to report about $10,000 in income from sports card and memorabilia shows. McCovey was given 2 years of probation and fined $5,000. President Barack Obama pardoned him just before leaving office in 2017. (Snider had died in 2011.)

In 1999, The Sporting News ranked McCovey 56th on their list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, and he was named a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. The following year, the Giants moved into what's now named AT&T Park. An inlet of San Francisco Bay beyond the right field fence was named McCovey Cove. A statue of him was dedicated outside the ballpark.

After his retirement, he worked in the Giants' front office as a "senior adviser" (much as Reggie does for the Yankees), and as a Spring Training instructor. He married twice, first to a woman named Karen, and they had a daughter, Allison. Earlier this year, at AT&T Park, he married Estela Bejar.

But his arthritic knees left him wheelchair-bound by 2002. In 2005, after another surgery, he said, "Lord, I've even lost count how many. It's at least a dozen on each knee." And you thought Mickey Mantle and Joe Namath had bad knees. They did. Willie's were worse.

In 2014, he was hospitalized with an infection that nearly killed him. This week, he was taken to Stanford University Medical Center in Palo Alto, California, with another infection. This time, the doctors couldn't stop it. Willie McCovey was 80 years old.

Orlando Cepeda said, "I'm very broken up. He was not only a teammate, but a brother."

If McCovey, Cepeda, Willie Mays, Juan Marichal, Bobby Bonds, and the rest of that 1st generation of San Francisco Giants were brothers, then future Giants have been cousins, as suggested by the tribute of Bobby's son, Barry Bonds: "I am crying over losing you, even when you told me not to. ... Uncle Mac thank you for your mentorship and unconditional love for me and my family. You will be dearly missed."

It was more than Willie's physical size, his talent, and the name of his team that made him a Giant. It was who he was.

UPDATE: He was buried at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park, in the San Francisco suburb of Colma, California. Also buried there: Baseball legends Lefty O'Doul and Dolph Camilli, singer Eddie Fisher, newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, and groundbreaking journalist Lincoln Steffens. Joe DiMaggio is also buried in Colma, but at Holy Cross Cemetery.

No comments:

Post a Comment